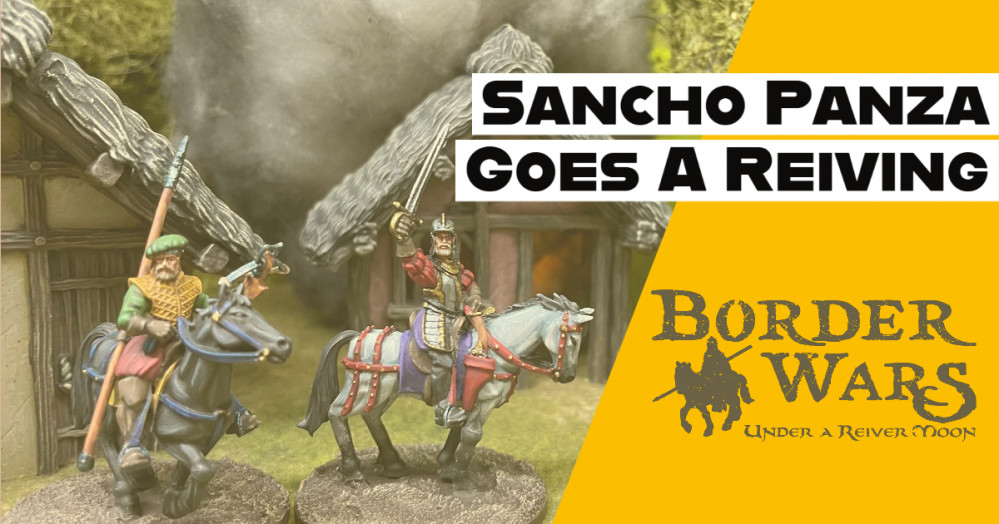

Sancho Panza goes to the Border Wars

Recommendations: 118

About the Project

Borders Wars: Under a Reiver Moon is a new skirmish game for raids by the Border Reivers in the mid to late 1500s on the Borders of Scotland and England. Like many periods throughout history, the outlaws have been romanticised and the Border Reivers are no different. These were turbulent times and many of the Reivers of the time wrote their name in the history of Scotland and England. Riding families were notorious for raiding each other for their livestock and with this came fire & steal to leave behind trails of blood that are still sung about to this day. The aim of Border Wars is to bring these families and their members to the gaming table and have gamers play out these raids.

Related Game: Border Wars: Under A Reiver Moon

Related Company: Flags Of War

Related Genre: Historical

This Project is Active

Sancho Panza's third Border reiver Video

I have uploaded the third video to my YouTube channel Panzerkaput’s Painting School for Scoundrels

This time I have painted three special cunning characters for my Border Wars game and a border family. All figures are from Flags of War – Flags & Miniatures

I hope you enjoy the video.

#borderwars, #borderreiver, #flagsofwar, #historicalgamer, #nowarhammer,

Sancho Panza's second Border Reiver Video Uploaded

New Video uploaded to my YouTube channel PanzerKaput’s Painting School for Scoundrels

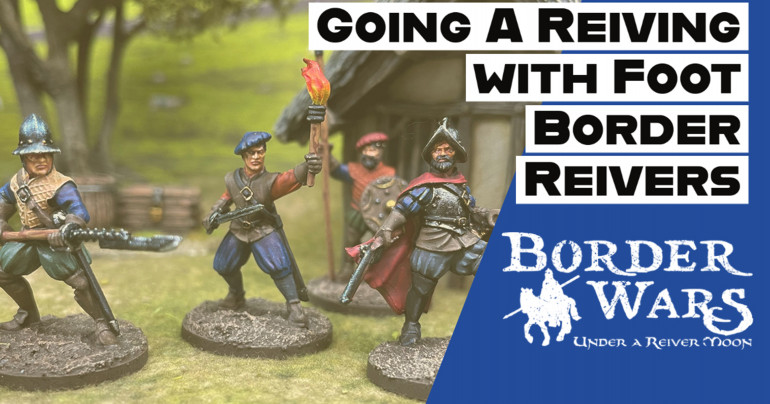

This time it is the turn of the Foot Border Reivers for Border Wars by Flags of War – Flags & Miniatures

I hope you like the video and if you do can you please like of subscribe

#borderwars, #borderreiver, #flagsofwar, #historicalgamer, #nowarhammer

Sancho Panza first Border Reiver Video uploaded

I have not done this for a while but Sancho Panza is back with a new video on my YouTube channel PanzerKaput’s Painting School for Scoundrels

This time it is a new period and I love of mine Border Reivers. These for the Border War Game from Flags of War.

I hope you enjoy the video and please like and subscribe if you can.

#borderwars, #borderreiver, #flagsofwar, #historicalgamer, #nowarhammer

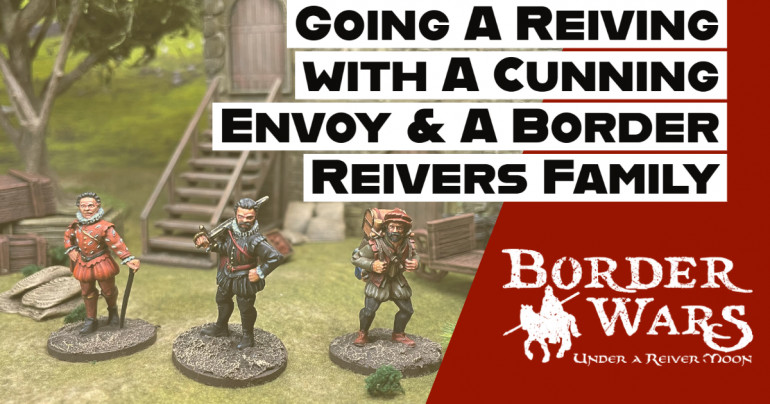

Border Reiver Family and a Characterful Envoy with a Cunning Plan

I have finished for last elements for my Border Wars starter set from Flags of War. This has to me brought the Border Reivers to life and I so love this range as it is so full of character. These are a border farmer’s family and a very well known Envoy, his unable assistant and cunny servant. They are so much fun.

Now I wait patiently for the Irish to come to the Borders.

#borderwars #flagsofwar #borderreiver

Border Reivers on Foot

I have finished the second Reiver family/force for Border Wars from Flags of War. This means I now have two forces and can play a game, once things settle down for me. These are foot reivers and I love the look and feel of these guys. Nearly completed the starter/kickstarter set now.

#borderwars #borderreiver #flagsofwar

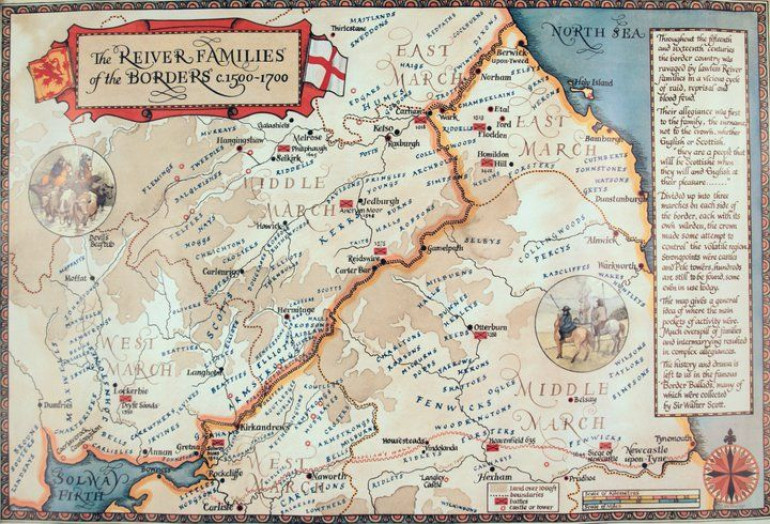

Border surnames and clans

A variety of terms describe the Border families, such as the “Riding Surnames” and the “Graynes” thereof. This can be equated to the system of the Highland Clans and their septs. e.g. Clan Donald and Clan MacDonald of Sleat, can be compared with the Scotts of Buccleuch and the Scotts of Harden and elsewhere. Both Border Graynes and Highland septs, however, had the essential feature of patriarchal leadership by the chief of the name, and had territories in which most of their kindred lived. Border families did practice customs similar to those of the Gaels, such as tutorship when an heir who was a minor succeeded to the chiefship, and giving bonds of manrent.

In an Act of the Scottish Parliament of 1587 there is the description of the “Chiftanis and chieffis of all clannis … duelland in the hielands or bordouris” – thus using the words ‘clan’ and ‘chief’ to describe both Highland and Lowland families. The act goes on to list the various Border clans. Later, Sir George MacKenzie of Rosehaugh, the Lord Advocate (Attorney General), writing in 1680 said “By the term ‘chief’ we call the representative of the family from the word chef or head and in the Irish (Gaelic) with us the chief of the family is called the head of the clan”. Thus, the words chief or head, and clan or family, are interchangeable. It is therefore possible to talk of the MacDonald family or the Maxwell clan. The idea that Highlanders should be listed as clans while the Lowlanders are listed as families originated as a 19th-century convention.

Surnames in the Marches of Scotland (1587)

In 1587 the Parliament of Scotland passed a statute: “For the quieting and keping in obiedince of the disorderit subjectis inhabitantis of the borders hielands and Ilis.” Attached to the statute was a Roll of surnames from both the Borders and Highlands. The Borders portion listed 17 ‘clannis’ with a Chief and their associated Marches:

Regions of the Scottish marches

Middle March

Elliot, Armstrong, Nixon, Crozier

West March

Scott, Bates, Little, Thompson, Glendenning, Irvine, Bell, Carruthers, Graham, Johnstone, Jardine, Moffat, and Latimer.

Of the Border Clans or Graynes listed on this roll, Elliot, Carruthers, Scott, Irvine, Graham, Johnstone, Jardine and Moffat are registered with the Court of Lord Lyon in Edinburgh as Scottish Clans (with a Chief), others such as Armstrong, Little and Bell are armigerous clans with no Chief, while such as Clan Blackadder, also an armigerous clan in the Middle Ages, later died out or lost their lands, and are unregistered with the Lyon Court.

The historic riding surnames recorded by George MacDonald Fraser in The Steel Bonnets (London: Harvill, 1989) are:

East March

Scotland: Hume, Trotter, Dixon, Bromfield, Craw, Cranston.

England: Forster, Selby, Gray, Dunn.

Middle March

Scotland: Burns, Kerr, Young, Pringle, Davison, Gilchrist, Tait of East Teviotdale. Scott, Oliver, Turnbull, Rutherford of West Teviotdale. Armstrong, Croser, Elliot, Nixon, Douglas, Laidlaw, Routledge, Turner, Henderson of Liddesdale.

England: Anderson, Potts, Reed, Hall, Hedley of Redesdale. Charlton, Robson, Dodd, Dodds, Milburn, Yarrow, Stapleton of Tynedale. Also Fenwick, Ogle, Heron, Witherington, Medford (later Mitford), Collingwood, Carnaby, Shaftoe, Ridley, Stokoe, Stamper, Wilkinson, Hunter, Huntley, Thompson, Jamieson.

West March

Scotland: Bell, Irvine, Johnstone, Maxwell, Carlisle, Beattie, Little, Carruthers, Glendenning, Routledge, Moffat.

England: Graham, Hetherington, Musgrave, Storey, Lowther, Curwen, Salkeld, Dacre, Harden, Hodgson, Routledge, Tailor, Noble.

Relationships between the Border clans varied from uneasy alliance to open, deadly feud. It took little to start a feud; a chance quarrel or misuse of office was sufficient. Feuds might continue for years until patched up in the face of invasion from the other kingdoms or when the outbreak of other feuds caused alliances to shift. The border was easily destabilised if Graynes from opposite sides of the border were at feud. Feuds also provided ready excuse for particularly murderous raids or pursuits.

Riders did not wear identifying tartans. The tradition of family tartans dates from the Victorian era and was inspired by the novels of Sir Walter Scott. The typical dress of reivers included Jack of plate, steel bonnets (helmets), and riding boots.

What are Border Reivers

Border Reivers were raiders along the Anglo-Scottish border from the late 13th century to the beginning of the 17th century. They included both Scottish and English people, and they raided the entire border country without regard to their victims’ nationality. Their heyday was in the last hundred years of their existence, during the time of the House of Stuart in the Kingdom of Scotland and the House of Tudor in the Kingdom of England.

Background

Scotland and England were frequently at war during the late Middle Ages. During these wars, the livelihood of the people on the Borders was devastated by the contending armies. Even when the countries were not formally at war, tension remained high, and royal authority in either or both kingdoms was often weak, particularly in remote locations. The difficulty and uncertainties of basic human survival meant that communities and/or people kindred to each other would seek security through group strength and cunning. They would attempt to improve their livelihoods at their nominal enemies’ expense, enemies who were frequently also just trying to survive. Loyalty to a feeble or distant monarch and reliance on the effectiveness of the law usually made people a target for depredations rather than conferring any security.

There were other factors which may have promoted a predatory mode of living in parts of the Borders. A system of partible inheritance is evident in some parts of the English side of the Borders in the sixteenth century. By contrast to primogeniture, this meant that land was divided equally among all sons following a father’s death; it could mean that the inheriting generation held insufficient land on which to survive. Also, much of the Border region is mountainous or open moorland, unsuitable for arable farming but good for grazing. Livestock was easily rustled and driven by mounted reivers who knew the country well. The raiders might also remove easily portable household goods or valuables, and take prisoners for ransom.

The attitudes of the English and Scottish governments towards the border families alternated from indulgence and even encouragement, as these fierce families served as the first line of defence against invasion across the border, to draconian and indiscriminate punishment when their lawlessness became intolerable to the authorities.

Reive, a noun meaning raid, comes from the Middle English (Scots) reifen. The verb reave meaning “plunder, rob”, a closely related word, comes from the Middle English reven. There also exists a Northumbrian and Scots verb reifen. All three derive from Old English rēafian which means “to rob, plunder, pillage”. Variants of these words were used in the Borders in the later Middle Ages. The corresponding verb in Dutch is “(be)roven”, and “(be)rauben” in German.

The earliest use of the combined term ‘border reiver’ appears to be by Sir Walter Scott in his anthology Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border. George Ridpath (1716?–1772), the author of posthumously-published The Border-History of England and Scotland, deduced from the earliest times to the union of the two crowns (London, 1776), referred not to ‘border reivers’ but only to banditti.

Nature

The reivers were both English and Scottish and raided both sides of the border impartially, so long as the people they raided had no powerful protectors and no connection to their own kin. Their activities, although usually within a day’s ride of the border, extended both north and south of their main haunts. English raiders were reported to have hit the outskirts of Edinburgh, and Scottish raids were reported to have reached as far south as Lancashire and Yorkshire. The main raiding season ran through the early winter months, when the nights were longest and the cattle and horses fat from having spent the summer grazing. The numbers involved in a raid might range from a few dozen to organised campaigns involving up to three thousand riders.

When raiding, or riding, as it was termed, the reivers rode light on hardy nags or ponies renowned for the ability to pick their way over the boggy moss lands (see: Galloway pony, Hobelar). The original dress of a shepherd’s plaid was later replaced by light armour such as brigandines or jacks of plate (a type of sleeveless doublet into which small plates of steel were stitched), and metal helmets such as burgonets or morions; hence their nickname of the “steel bonnets”. They were armed with light lances and small shields, and sometimes also with longbows, or light crossbows, known as “latches”, or later on in their history with one or more pistols. They invariably also carried swords and dirks.

Borderers as soldiers

Border reivers were sometimes in demand as mercenary soldiers, owing to their recognised skills as light cavalry. Reivers sometimes served in English or Scottish armies in the Low Countries and in Ireland, often to avoid having harsher penalties enacted upon themselves and their families. Reivers fighting as levied soldiers played important roles in the battles at Flodden and Solway Moss. After meeting one reiver (the Bold Buccleugh), Queen Elizabeth I is quoted as having said that “with ten thousand such men, James VI could shake any throne in Europe.”

These borderers proved difficult to control, however, within larger national armies. They were already in the habit of claiming any nationality or none, depending on who was asking and where they perceived the individual advantage to be. Many had relatives on both sides of Scottish-English conflicts despite prevailing laws against international marriage. They could be badly behaved in camp, seeing fellow soldiers as sources of plunder. As warriors more loyal to clans than to nations, their commitment to the work was always in doubt. At battles such as Ancrum Moor in Scotland in 1545, borderers changed sides in mid-combat to curry favour with the likely victors. At the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547, an observer (William Patten) noticed Scottish and English borderers chatting with each other, then putting on a spirited show of combat once they knew they had been spotted.

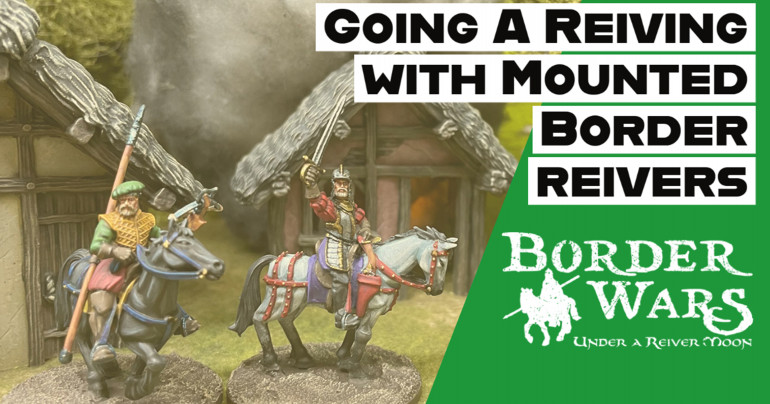

Mounted Reivers

This is the start of my Border Reiver, Border Wars project. I have to admit I have been in love the Border Reivers since childhood, about the fights of the border families, the cattle raiding, blood feuds, in the 16/17th century, just like the Wild West but instead on the borders of England and Scotland and later in Ireland too.

As the period is late Tudor, early Stuarts, I have aimed for the look of that time, you know, Blackadder 2, and wanted that every day look, not uniformed, and I hope I have achieved that.

This is my first Family, warband/gang, which is for a medium size game, and the next family will be on foot.