PanzerKaput Goes To Barons’ War

Recommendations: 11323

About the Project

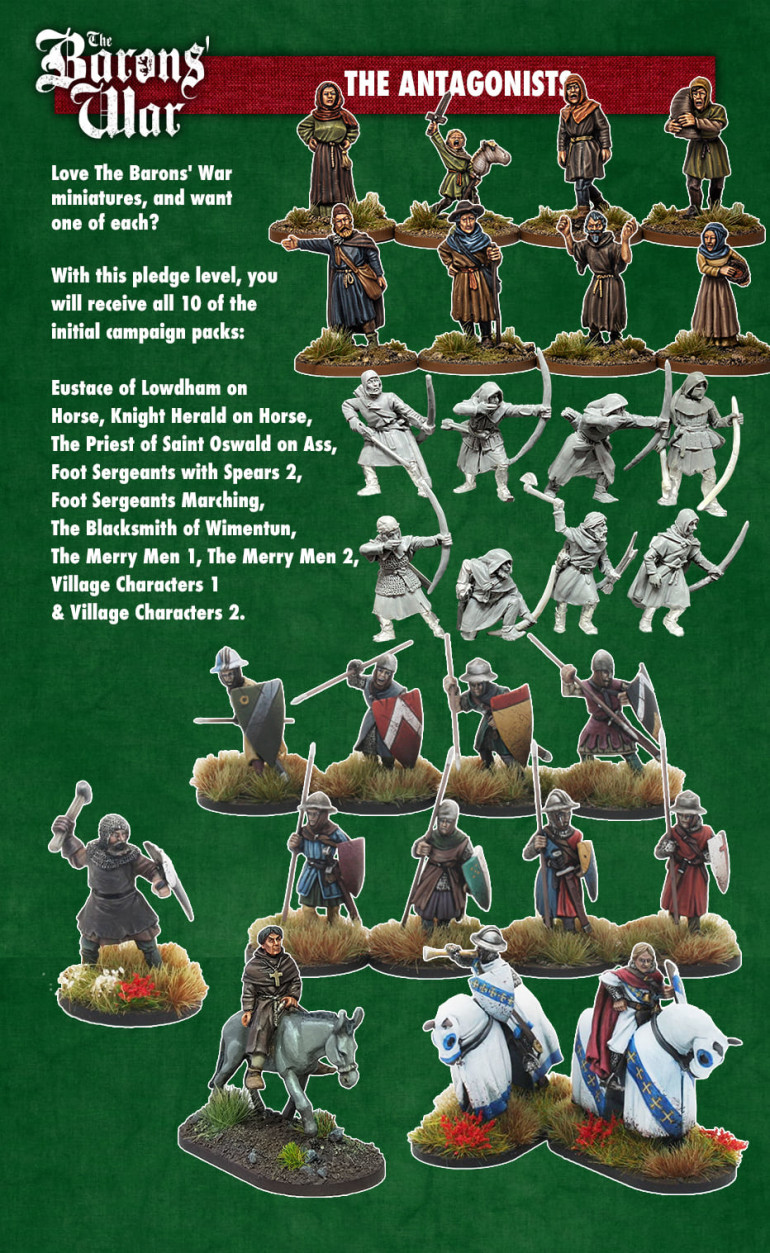

Set against a backdrop of a Civil War that lasted for two years, 1215-17, as a result of the issuing of Magna Carta. A civil war was the perfect opportunity for the leading nobles of the time to grab land and power while settling some old scores along the way. This vying for land and power hadn't stopped since the invasion of 1066 with only the strongest of kings being able to keep their nobles in check. Our narrative focuses on small groups of warriors brought together under a lord or baron to raid and steal or defend land and property. With the strong, wise, cunning and lucky aiming to rise out of this civil strife in a better position than when it started. The Barons' War skirmish game has been written to enable players to fight out tabletop battles against the backdrop of the First Barons’ War between rival Barons or rival factions who find themselves on either side of the conflict. The game is historically themed, the gameplay is fast-paced and tactical with plenty of narrative and where force building presents you with lots of options enabling two players to muster very different retinues. However, as intended, this is an alpha set of rules which does not include rules for siege warfare, although rules for fighting in buildings are included. Campaign rules are something that will be addressed at a later date and released online. Having grown out of the Barons’ War Kickstarter project, the intention is for this ruleset to develop into a system that could be used throughout the Medieval period. Starting with England from when the Western Roman Empire withdrew around 410 AD to 1485 AD when Richard III died at the Battle of Bosworth Field. This presents us with a huge span of history for gaming which can be broadly divided into Romano-British, Anglo-Saxon and Viking, Anglo-Norman, Angevin and Plantagenet. And that’s just when looking at it from Great Britain. With warriors of this period being pretty similar, it would be easy to use the profiles in this rulebook to play out tabletop battles in any setting. Over time we see these rules evolving with additional warriors, characters, abilities and scenarios being added starting with the Dark Ages, the Anarchy and the Crusades and shared to www.warhost.online, which has been set up to be the community website for the game.

Related Game: The Barons' War

Related Company: Footsore Miniatures and Games

Related Genre: Historical

This Project is Active

Its a Hard Days Knight

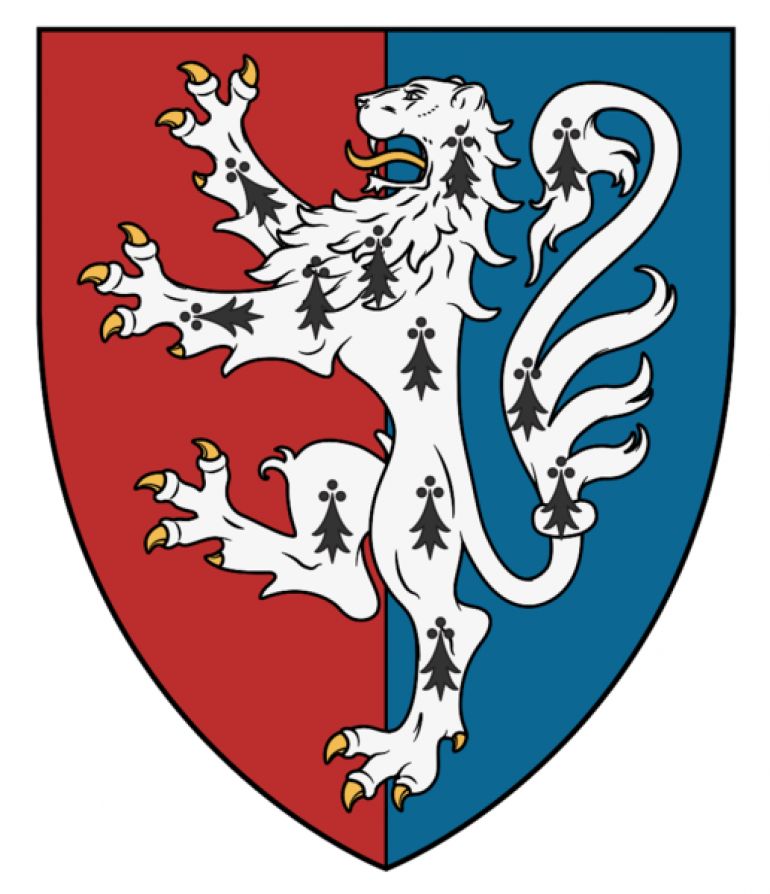

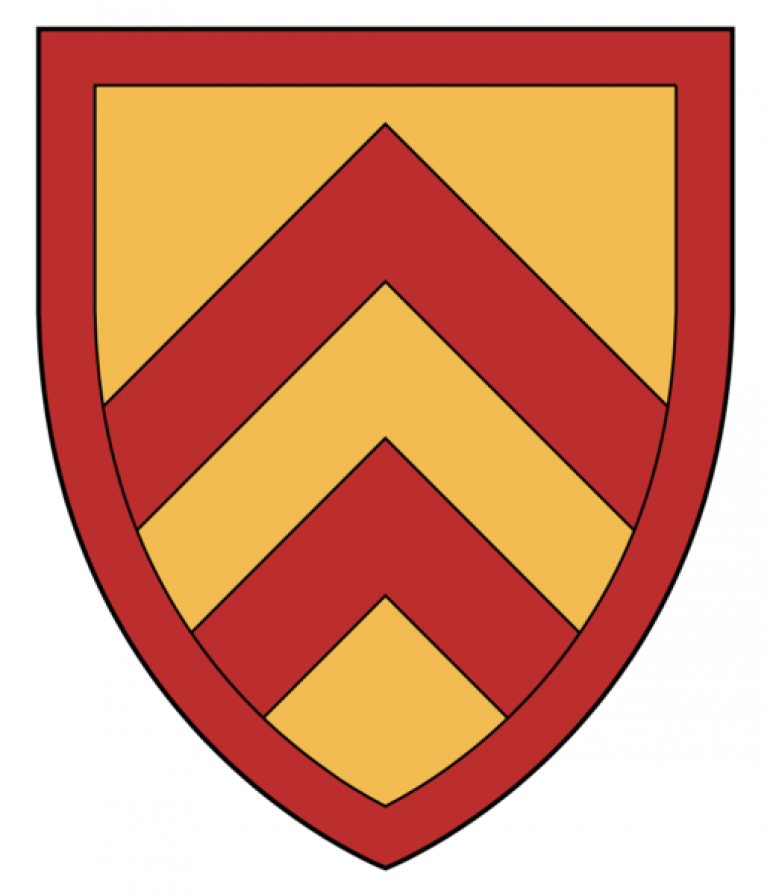

I have finished my second unit of foot knights for my second Baronial force and again I have gone for that individual look to the knights as they would have they own livery and shield design and not one of their Lords. It is fun painting these and researching into them, but there is not a lot of information on who they worn, what the Rolls of Arms were and if they even had liveries and tabards. That to me is the fun part and in my head making up the names of the knights so I have characters on the battlefield.

Barons' War Three Kickstarter Coming Soon

Richard and Gilbert de Clare

The de Clares were one of the great baronial families of twelfth- and thirteenth-century England, holding wide estates in eastern and western England and beyond. For a while the senior branch, based at Tonbridge (Kent), was eclipsed in fame and fortune by a brilliant junior branch which established itself in South Wales and the Marches. Richard FitzGilbert de Clare of this branch, known to history as ‘Strongbow’, was the leader of the semi-official Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in Henry II’s reign and obtained a grant of the lordship of Leinster from the king in 1171. This cadet branch became extinct in the male line on the death of Strongbow’s son Gilbert in 1185 and the family’s estates were later taken over by the Marshal earls of Pembroke.

Richard de Clare, appointed to the Twenty Five, of the senior branch of the family, was the son of Roger de Clare (d. 1173), lord of Tonbridge, who was in turn the younger brother and successor of Gilbert II (d. 1152), to whom King Stephen had granted the title earl of Hertford in or around 1138. In the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries the earls used the title ‘of Hertford’ interchangeably with that of earl of Clare.

For over four decades until his death in 1217 Earl Richard was the effective head of the house of Clare. He does not appear to have been especially active, however, playing little part in national affairs either in the last years of Henry II’s reign or in that of Richard the Lionheart. He only emerged as a figure of political importance towards the end of his life in the crisis of John’s reign, when he was appointed to the Twenty Five, most probably in recognition less of his personal qualities than his family’s exalted standing in the realm.

Earl Richard’s greatest and most lasting achievement was to add to the already considerable wealth and landed endowment of his line. In 1189 at the beginning of Richard’s reign, in a major acquisition, he received a grant of half of the honor (or feudal lordship) of the Giffard earls of Buckingham, which had escheated to the crown over twenty years before following the death of the last earl, Walter. The Lionheart effected an equal division between Earl Richard and his cousin Isabel, daughter of Strongbow and wife of William Marshal, earl of Pembroke, both of whom claimed descent from Roesia, Walter’s aunt and wife of Richard FitzGilbert de Clare, first founder of the family.

In 1195 Earl Richard made another substantial, though less perhaps important, addition to his family’s inheritance when he obtained the feudal honor of St Hilary on the death of his mother Maud, Earl Roger’s widow. The honor, for which Richard offered £360 to the Crown, included lands in Norfolk and Northamptonshire.

The most substantial of all the additions Earl Richard made to the family estate, however, came as a result of his marriage to Amicia, second daughter and eventual sole heiress of William, earl of Gloucester. The Gloucester inheritance was a vast one, comprising over 260 knights’ fees in England and extensive lands in Wales and the Marches. The story of its partition among the three daughters and co-heiresses is long and complex. Mabel, the eldest of the three, was married to Amaury de Montfort, count of Evreux in Normandy, while Isabel, the third and youngest, was married to the future King John. Mabel’s marriage was childless and on her husband’s death her lands passed to Isabel. John, however, on becoming king, divorced Isabel so that he could marry the Poitevin heiress Isabella of Angouleme, giving his now ex-wife in marriage to Geoffrey de Mandeville, another of the Twenty Five, and charging him 20,000 marks for the privilege. After Geoffrey died in 1216 her hand was taken by a third husband, Hubert de Burgh, but she herself died in 1217, and her estates passed to Amicia and her husband, Earl Richard. Earl Richard survived Isabel by only six weeks and did not live to secure formal seisin of her estates and title. It was left to his son and heir Gilbert, another of the Twenty Five, to succeed to the vast Gloucester inheritance. Shortly after his father’s death Gilbert assumed the combined titles of earl of Gloucester and Hertford. Countess Amicia lived out her last years in retirement, probably at Clare, having been separated from her husband, for reasons unknown, since 1200.

Earl Gilbert was an active participant on the baronial side in the civil war that followed in the wake of King John’s rejection of Magna Carta. He fought with Louis and the French at the battle of Lincoln in May 1217 and was taken captive by none other than William Marshal, the Regent, whose daughter, Isabel, he was later to marry. In 1225 he was a witness to Henry III’s definitive reissue of Magna Carta. In 1230 he accompanied Henry on his expedition to Brittany, but died on the way back at Penros, in the duchy. The earl’s body was brought by way of Plymouth to Tewkesbury, where he was buried before the high altar of the great abbey. A monument, now lost, was erected to his memory by his widow.

By a strange irony, the de Clare family, like their predecessors in the Gloucester title, was to come to an end in 1314, after the death of the last earl, in the succession of three daughters and coheiresses and the partition of the family estates between them.

William de Mowbray

I have finished the commander for my second force, William de Mowbray, 6th Baron of Thirsk, 4th Baron Mowbray (c. 1173–c. 1224) was a Norman Lord and English noble who was one of the twenty-five executors of Magna Carta. He was described as being as small as a dwarf but very generous and valiant.

William de Mowbray's Spearmen

I have finished my first unit of spearmen for William de Mowbray’s force, my second force and additional force to be added to the Abbot William Pepyn’s force. I have gone for a simple, everyday wear for the clothing but have added a red tunic, tabard on a couple of this to make them feel like a unified, single force.

I love the sculpts and the character that Paul Hick’s has got into these is amazing.

Roger and Hugh Bigod

The Bigods were a major East Anglian landowning family, based at Framlingham (Suffolk), who had held the earldom of Norfolk since its grant to Hugh Bigod in 1140 or 1141. Roger (c. 1143-1221) was the only son of this Hugh by his first wife, Juliana, sister of Aubrey de Vere, earl of Oxford.

Roger’s father had left him a tangled inheritance. He had repudiated his son’s mother and had subsequently married Gundreda, daughter of Roger, earl of Warwick, by whom he had two more sons, Hugh and William, for whom their mother, after their father’s death in 1176 or 1177, sought to make provision out of the family inheritance at their elder half-brother’s expense. Henry II, savouring the opportunity to gain his revenge on Hugh for his involvement in the rebellion against him in 1173-4, deliberately left the case unresolved, refused to allow the son to succeed to the father’s earldom, and confiscated the lands in dispute between the heir and the half-blood. Roger was only able to vindicate his rights on Richard I’s accession in 1189, when the earldom was granted to him on payment of the relatively low relief of one thousand marks (£666).

Thereafter Roger enjoyed a long and honourable career in royal service. He served Richard as a justice in eyre (i.e. itinerant judge) and as a baron of the exchequer. In John’s reign he took part in the defence of Normandy, and after 1206 served on campaigns in Poitou and within the British Isles. In 1215, however, he went over to the opposition, joining the rebel barons in their muster at Stamford. In part, his involvement on the rebel arose in response to the financial pressures exerted on him by the king. The scutage – money due in lieu of personal military service – that the earl owed from his many estates was so substantial that in 1211 he was driven to striking a deal with the exchequer to pay 2000 marks (£1333) for respite during his lifetime from demands for arrears and for liability to a reduced sum in future. Roger had various other grievances against the king. One at least related to litigation. In 1207, when a legal action had been brought against him in the royal courts, he objected to the chosen jurors on grounds of their likely bias, but his arguments had been ignored by the king, who ordered the case to proceed.

Roger was joined in his rebellion by his son and heir Hugh, who was already of full age, and the two stood in the forefront of the opposition in East Anglia. In March 1216 the king succeeded in taking the family’s main castle at Framlingham and put pressure on the earl by pardoning those of his followers whom he captured, while condemning those who refused to submit to forfeiture of their lands. Roger and Hugh did not return to their allegiance until after the general peace settlement agreed with Henry III’s Minority government at Kingston-on-Thames in September 1217. By April of the following year the earl had received back all his lands and titles, but, by now over 70, he was in semi-retirement and he died three years later in 1221. He was succeeded as earl by his son, another of the Twenty Five, who in 1206 or 1207 had married Matilda, daughter of the future Regent, William Marshal, earl of Pembroke. The son died in February 1225.

Framlingham castle, as we see it today, is largely the product of a rebuilding carried out by Earl Roger in Richard the Lionheart’s reign, following the partial demolition of the fabric by Henry II in 1174. It consists of a cluster of baileys set on a low eminence above a flooded mere. The inner bailey, which constituted its central space, was innovative in taking the form of an irregular-shaped curtain wall punctuated at intervals by open-backed towers, dispensing great tower or keep customary in Norman castles.

William d’Albini, Baron of Belvoir

William d’Albini (d’Aubigny) was a relative latecomer to the baronial opposition cause, but one of the movement’s ablest military commanders and the leader of the defence of Rochester against King John in 1215. After John’s son, Henry III, succeeded to the throne in 1216, he showed himself a loyal supporter of the new regime.

William (after 1146–1236) was the son of William d’Albini II by his wife Maud FitzRobert, the grandson of another William, known as ‘Brito’, and the eventual heir of the first post-Conquest lord of Belvoir, Robert de Todeni. William’s lordship was an extensive one stretching across the east and north Midlands, comprising some 33 knights’ fees, in part overlooked from Belvoir (Leics.) itself, dramatically sited on a high ridge west of Grantham.

William, like a number of the Twenty Five, embarked on the path to rebellion with reluctance being by both upbringing and instinct a natural royalist. He had had long experience of serving in royal administration. In 1195 and 1197, under Richard, he had held office as sheriff of Warwickshire and Leicestershire and in John’s first year he was appointed to the same office in Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire. In 1200 he had served as a custodian or justice exercising supervision of the Jews, and in 1210 he was appointed with other lords to supervise collection of tolls in the ports. In February 1213, as John’s suspicions of the northern lords were deepening, he served as a commissioner to look into money allegedly collected by sheriffs and other officials that never found its way into the royal coffers.

William eventually joined the opposition shortly after the fall of London in May 1215, doing so probably for a number of reasons. Almost certainly he was growing disenchanted with the oppressive nature of John’s kingship. Five years before, he had been a witness to John’s official account of the reasons for his destruction of the Braose family, thereby associating himself with the king’s actions, while yet becoming aware of their arbitrariness. At the same time, like other lords, he was feeling the acute financial burden of John’s misrule. As late as 1230, more than a decade into Henry III’s reign, he still owed no less than £3,308 to the Crown of old debts dating from John’s reign. In company with others of the Twenty Five, he could be counted among the debtors of 1215. Finally, he is almost certain to have been influenced by the ties of kinship. He was the first cousin of Robert FitzWalter, lord of Dunmow, to all intents and purposes the leader of the revolt, and was the uncle of another rebel, Robert de Ros, the lord of Helmsley. It may also be significant that among his knightly tenants was Nicholas de Stuteville of Knaresborough, the greatest baronial debtor of all.

In June 1215 his experience and social standing ensured his appointment to the Twenty Five and from the autumn, after the renewal of war, he fought actively on the baronial side. In July, after the barons had gone their separate ways, Robert FitzWalter was writing to him to advise of a change of meeting-place for a tournament from Stamford to Hounslow Heath. John’s strategy in the civil war was to counter the baronial challenge by bringing in a force of mainly Flemish mercenaries to help re-take London. The barons, to prevent these men’s passage inland from Dover, made for Rochester, at the bridging point over the Medway, and quickly took the castle, installing William as constable. John retaliated by immediately embarking on siege operations. The castle, though ill-provisioned, was well manned, with some 95 knights and 45 men-at-arms under William’s command, and strong resistance was offered. Both sides fought fiercely. ‘Living memory does not recall a siege so closely pressed or so bravely resisted’, wrote the Barnwell chronicler. To eke out the meagre food rations in the castle, d’Albini ordered the sick and the wounded to be ejected, a common tactic in sieges at the time; according to the Barnwell writer, the king had their hands and feet cut off. The turning-point in the siege came in November, when the king’s men successfully undermined one of the keep’s corner towers, bringing it down, and opening a way in. William had no alternative but to surrender, and he and his garrison were sent off to captivity at Corfe.

Following this success, the king made his way to the Midlands, where he directed the siege of William’s castle at Belvoir. After he had issued a threat to starve William himself if the garrison held out, the latter’s son Nicholas, who was heading the defence, hastily offered his surrender. William regained his freedom in November 1217, when he agreed to a fine of 6,000 marks and to the surrender of his wife as a hostage for his good behaviour. His career from now on was that of a committed supporter of the new Minority regime. He fought on the Regent’s side at Lincoln, and his loyalty earned its reward in his appointment as constable of Sleaford Castle. In 1223 he joined the young Henry III on his campaign against Prince Llewellyn and the Welsh at Builth Wells and Montgomery. Two years after that, he was one of the group of counsellors who witnessed the final and definitive reissue of Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest.

William died on 1 May 1236 at his manor of Uffington, near Stamford (Lincs.). His remains were interred in the priory which he had founded at Newstead, just outside the village; his heart, however, was removed for separate burial at Belvoir Priory. Between 1221 and the early 1230s the future chronicler, Roger Wendover, was prior of Belvoir, a dependent house of St Albans. It seems very likely that he was indebted to d’Albini for his account of the siege of Rochester, which is full of circumstantial detail.

William was twice married. His first wife was Margery, daughter of Odinel de Umfreville of Prudhoe (Northumberland), whose date of death is unknown, and his second, Agatha, sister and coheir of Robert Trussebut of Hunsingore (Yorks.). William’s heir was yet another William, who died in 1247 leaving only daughters, one of whom, Isabel, married Robert de Ros (d. 1285) of Helmsley, descendant of the lord of that name who was of the Twenty Five, so carrying the d’Albini inheritance to the Ros family.

The family of d’Albini of Belvoir is not to be confused with that of the same name based at Old Buckenham (Norfolk) and Arundel (Sussex), which held the title of earl of Arundel.

Baron William de Mowbray

William de Mowbray (c. 1173-c. 1224), a landowner with Yorkshire estates centring on Thirsk and Lincolnshire lands in the Isle of Axholme, was son of Nigel de Mowbray and his wife Mabel, probably the daughter of William de Patri. In the Histoire des Ducs de Normandie he is described as being as small as a dwarf, but very generous and valiant. There was much in William’s background and personal circumstances that can be seen, with hindsight, as pointing the way to his involvement in the rebellion against King John.

His forebear, Roger de Mowbray, had taken part in the great uprising against Henry II in 1173-4, which had convulsed the whole Angevin world. He himself had become entangled in financial dealings with King John which were to cost him dearly. His problems lay in his family’s early rise to power, specifically in their acquisition from Henry I a century before of the lands of Robert de Stuteville, a supporter of Henry’s brother Robert Curthose in his failed bid for the English crown, and who had forfeited his property to Henry.

In 1200 Robert’s descendant, William, reactivated his family’s claim against the Mowbrays, and in that year William offered the sum of 2000 marks (over £1300) to John to secure a judgement in the matter. When the case was brought before the king’s justices, however, it ended in a compromise, and one highly favourable to Stuteville. William was nonetheless still under obligation to pay and, like others before him, had little alternative but to borrow from the Jews. William had gambled everything on the favourable outcome of a risky legal action and had failed. It is clear that, when he embarked on rebellion against John, he had nothing to lose.

Mowbray was taken prisoner at the battle of Lincoln in May 1217, and had to surrender the manor of Banstead in Surrey, which had formed his mother’s marriage portion, to Hubert de Burgh as the price of redemption. His family never succeeded in recovering the estate. Mowbray founded the chapel of St Nicholas at Thirsk, and was a benefactor of his father’s foundation, Newburgh priory, where, on his death at Axholme around 1224, he was buried.

Mowbray was typical those lords, particularly in northern England, who had suffered at the hands of John, felt a burning sense of grievance, and were longing for the opportunity to get their own back.

Pimping up a Medieval Cottage

I like the some for $ground and actually that do some very nice stuff but they do look a little toy like. I have have added a little bit of paint, textured mud paint and a wash with Vallejo Black Wash and a drybrush with Iraqui Sand and it looks much better, less toy like and sit nicely in the battlefield. But what do you think?

The Start of my Second Force

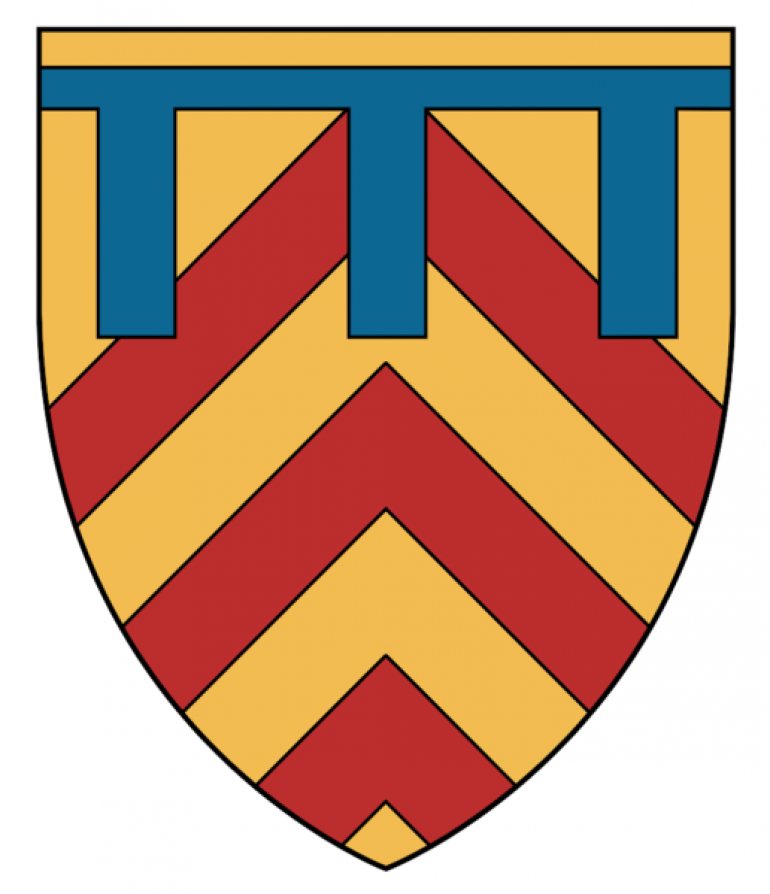

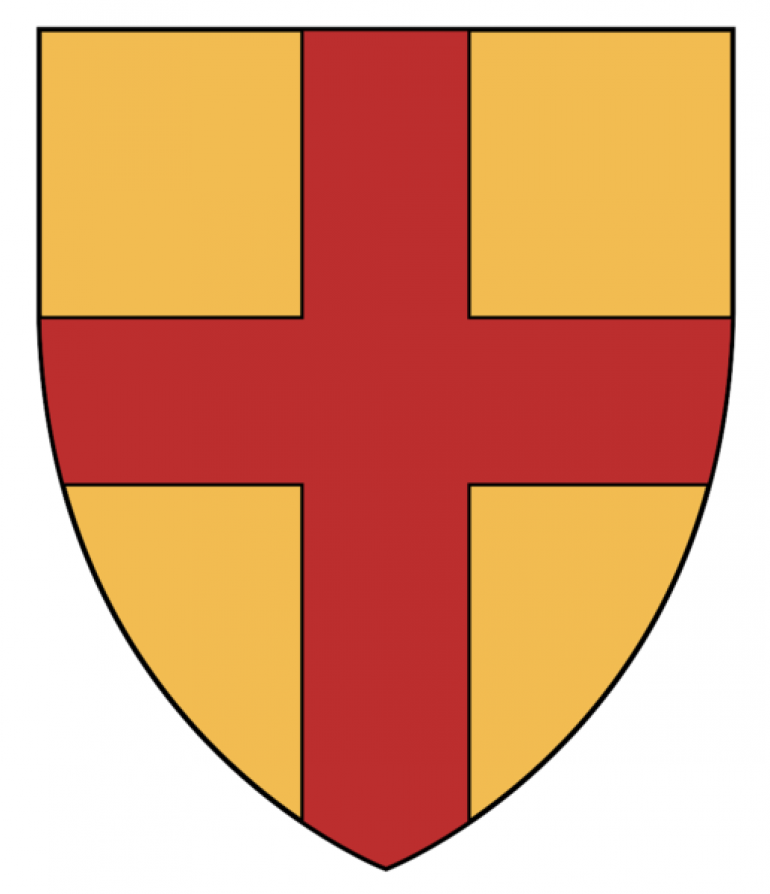

This is the start of my second force for Barons’ War and this can be and will be added to the first force to give a larger force for bigger games. This force is based around a Baronial force of William de Mowbray. I wanted to give these knights a more individual feel to them as is fitting knights, though not Barons as still important enough to have their on livery.

I have hand painted the shield and in fact I am really enjoying painting them and I personally think it give a more authentic feel to them. I will get around to namely them in the future as I want to give them a personally. But what you you think?

Henry de Bohun

Henry de Bohun was a member of the Essex-based family grouping brought to the rebel cause by kinship with Geoffrey de Mandeville and Robert FitzWalter. His family also held important blocks of lands in the west of England.

Henry (c. 1175–1220) was the son of Humphrey de Bohun (d. 1181) and Margaret (d. 1201), daughter of Henry, earl of Northumberland, and widow of Conan IV, duke of Brittany. His grandmother was Margaret de Bohun, the daughter of Miles of Gloucester, earl of Hereford, one of the earliest and most consistent supporters of the Empress Matilda in the civil war of King Stephen’s reign. Margaret brought to the de Bohuns her family’s claims to the royal constableship and to the earldom of Hereford. The constable’s office had been granted to her son – Henry’s father – by 1174 and was therefore inherited by Henry himself, who used the style ‘Henry the Constable’ in a number of his early charters. Despite his youth he occasionally attested charters of Richard I and was one of the king’s sureties in negotiations with the count of Flanders in 1197.

John bestowed the title earl of Hereford on Henry in 1200, albeit prohibiting him from staking any claim to the generous grants which Henry II had made in a charter to his ancestor Earl Roger of Hereford. His grandmother’s keen advocacy had been a factor in this success, but equally significant was the fact that his mother was a granddaughter of David I, king of Scotland, and his uncle William the Lion, a later king of the same. Between 1204 and 1211 he was engaged in a lengthy dispute to establish his claim to a part of his mother’s dower lands, the valuable lordship of Ryhall in Rutland. No sooner had this dispute been settled than he found himself dragged into further litigation, countering a claim by the king’s half-brother, William Longespée, earl of Salisbury, to his lordship of Trowbridge (Wilts.) on the pretext of descent from an earlier owner, Edward of Salisbury. This long drawn-out dispute was to lead to a sharp deterioration in his relations with King John. Longespée initiated the action in1212 and Earl Henry responded by resort to the time-wasting tactics characteristic of the time, pleading illness as an excuse for absence from hearings. As such an excuse was inadmissible in this sort of case, the king took the lordship into his own hands, while allowing Longespée to levy scutage (money in lieu of military service) from its tenants. The sense of hurt which the earl felt was a major factor in his support for the rebels in 1215, as John’s seizure of the lordship constituted a disseisin made ‘unjustly and without judgement’, in the wording of clause 39 of the Charter. A further claim on his allegiance was made by the ties of kinship: his wife was Maud, daughter of Geoffrey FitzPeter and therefore aunt of Geoffrey de Mandeville. By virtue of his involvement on the rebel side in 1215 he secured the restoration of the lordship, although not of the castle, of Trowbridge. Letters ordering the estate’s restitution to him were among the first to be issued in execution of the Charter. The dispute dragged on, however, and a final settlement was not reached until 1229, when Edward of Salisbury’s honour was divided equally between the claimants, Trowbridge itself going to the Countess Ela, Longespée’s widow.

On the death of King John he remained loyal to the rebel cause and he was taken prisoner with the other rebel leaders at the battle of Lincoln in May 1217. As part of the general settlement in September he made his peace with the Minority government, subsequently attending the young Henry III’s court, receiving the earl’s third penny of Herefordshire and accounting for scutage. He died on pilgrimage to the Holy Land on 1 June 1220, leaving a son and heir, Humphrey. His widow took as her second husband, sometime between 1221 and 1226, one Sir Roger de Dauntsey and succeeded in her own right to the earldom of Essex, which on her death was inherited by her son.

Earl Henry was buried in the chapter house of Llanthony priory, near Gloucester, the traditional burial place of the Bohuns. He was succeeded in the title by his son and heir, Humphrey, who was to live until 1275.

Earl Henry was a notable figure in the development of modern Trowbridge, as it was he who secured the grant of a market and annual fair from the Crown in 1200. From this privilege flowed the laying out of the market place along the curved line of the castle ditch, the removal of the church from the castle’s inner bailey and the construction of the present church of St James in the heart of the town. It is likely that the earl’s considerable investment in Trowbridge helps to explain his keenness to retain possession of the town in the face of William Longespée’s persistent claims.

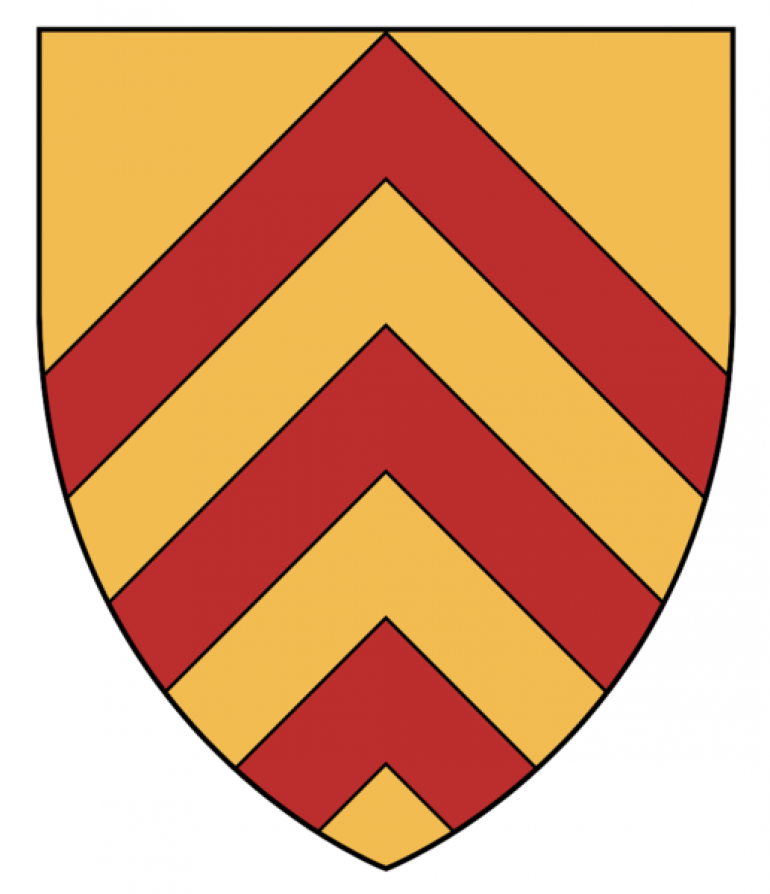

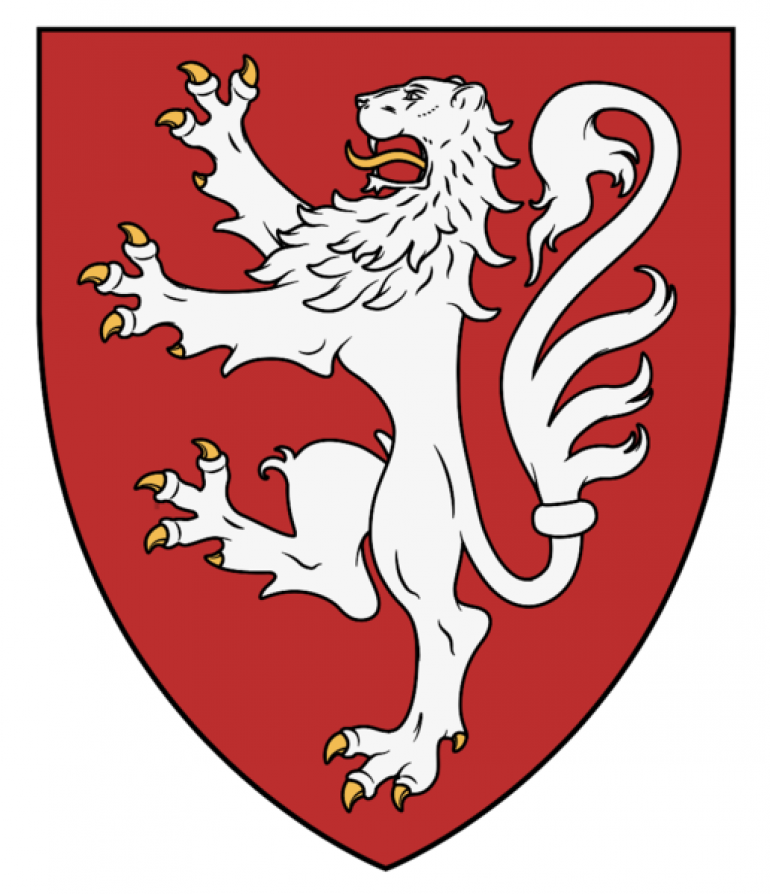

Heraldry and Shields Designs

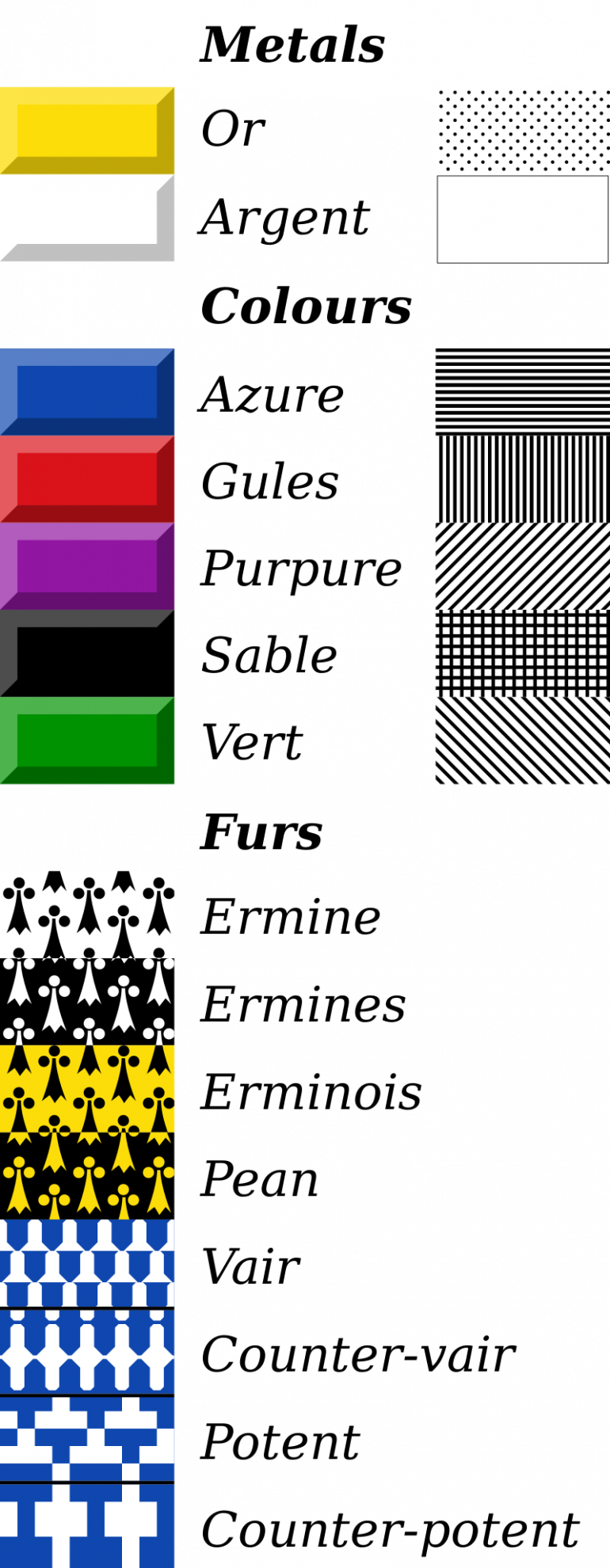

Tincture is the limited palette of colours and patterns used in heraldry. The need to define, depict, and correctly blazon the various tinctures is one of the most important aspects of heraldic art and design.

Development and history

The use of tinctures dates back to the formative period of European heraldry in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The range of tinctures and the manner of depicting and describing them has evolved over time, as new variations and practices have developed.

The basic scheme and rules of applying the heraldic tinctures dates back to the 12th century. The earliest surviving coloured heraldic illustrations, from the mid-thirteenth century, show the standardized usage of two metals, five colours, and two furs. Since that time, the great majority of heraldic art has employed these nine tinctures.

Over time, variations on these basic tinctures were developed, particularly with respect to the furs. Authorities differ as to whether these variations should be considered separate tinctures, or merely varieties of existing ones. Two additional colours appeared, and were generally accepted by heraldic writers, although they remained scarce, and were eventually termed stains, from the belief that they were used to signify some dishonour on the part of the bearer. The practice of depicting certain charges as they appear in nature, termed proper, was established in the seventeenth century. Other colours have appeared occasionally since the eighteenth century, especially in continental heraldry, but their use is infrequent, and they have never been regarded as particularly heraldic, or numbered among the tinctures that form the basis of heraldic design.

Frequency and national variants

The frequency with which different tinctures have been used over time has been much observed, but little studied. There are some general trends of note, both with respect to the passage of time, and noted preferences from one region to another.

In medieval heraldry, gules was by far the most common tincture, followed by the metals argent and or, at least one of which necessarily appeared on the majority of arms. Among the colours, sable was the second most common, followed by azure. Vert, although present from the formative period of heraldic design, was relatively scarce. Over time, the popularity of azure increased above that of sable, while gules, still the most common, became less dominant. A survey of French arms granted during the seventeenth century reveals a distinct split between the trends for the arms granted to nobles and commoners. Among nobles, gules remained the most common tincture, closely followed by or, then by argent and azure at nearly equal levels; sable was a very distant fifth choice, while vert remained scarce. Among commoners, azure was easily the most common tincture, followed by or, and only then by gules, argent, and sable, which was used more by commoners than among the nobility; vert, however, was even scarcer in common arms. Purpure is so scarce in French heraldry that some authorities do not regard it as a “real heraldic tincture”.

On the whole, French heraldry is known for its use of azure and or, while English heraldry is characterized by heavy use of gules and argent, and unlike French heraldry, it has always made regular use of vert, and occasional, if not extensive, use of purpure. German heraldry is known for its extensive use of or and sable. German and Nordic heraldry rarely make use of purpure or ermine, except in mantling, pavilions, and the lining of crowns and caps. In fact, furs occur infrequently in German and Nordic heraldry.

Metals

The metals are or and argent, representing gold and silver respectively, although in practice they are often depicted as yellow and white.

Or (Ger. Gelb, Gold, or golden) derives its name from the Latin aurum, “gold”. It may be depicted using either yellow or metallic gold, at the artist’s discretion; “yellow” has no separate existence in heraldry, and is never used to represent any tincture other than or.

Argent (Ger. Weiß, Weiss, Silber, or silbern) is similarly derived from the Latin argentum, “silver”. Although sometimes depicted as metallic silver or faint grey, it is more often represented by white, in part because of the tendency for silver paint to oxidize and darken over time, and in part because of the pleasing effect of white against a contrasting colour. Notwithstanding the widespread use of white for argent, some heraldic authorities have suggested the existence of white as a distinct heraldic colour.

Colours

Five colours have been recognized since the earliest days of heraldry. These are: gules, or red; sable, or black; azure, or blue; vert, or green; and purpure, or purple.

Gules (Fr. gueules, Ger. Rot) is of uncertain derivation; outside of the heraldic context, the modern French word refers to the mouth of an animal.

Sable (Ger. Schwarz) is named for a type of marten, known for its dark, luxuriant fur.

Azure (Fr. azur or bleu, Ger. Blau) comes through the Arabic lāzaward, from the Persian lāžavard both referring to the blue mineral lapis lazuli, used to produce blue pigments.

Vert (Fr. vert or sinople, Ger. Grün) is from Latin viridis, “green”. The alternative name in French, sinople, is derived from the ancient city of Sinope in Asia Minor, which was famous for its pigments.

Purpure (Fr. purpure or pourpre, Ger. Purpur) is from Latin purpura, in turn from Greek porphyra, the dye known as Tyrian purple. This expensive dye, known from antiquity, produced a much redder purple than the modern heraldic colour; and in fact earlier depictions of purpure are far redder than recent ones. As a heraldic colour, purpure may have originated as a variation of gules.

Stains

Two more tinctures were eventually acknowledged by most heraldic authorities: sanguine or murrey, a dark red or mulberry colour; and tenné, an orange or dark yellow to brownish colour. These were termed “stains” by some of the more influential heraldic writers, and supposed to represent some sort of dishonour on the part of the bearer; but in fact there is no evidence that they were ever so employed, and they probably originated as mere variations of existing colours. Nevertheless, the belief that they represented stains upon the honour of an armiger served to prevent them receiving widespread use, and it is only in recent times that they have begun to appear on a regular basis.

Sanguine or Murrey, from Latin sanguineus, “blood red”, and Greek morum, “mulberry”, one of the two so-called “stains” in British armory, is a dark red or mulberry colour, between gules and purpure in hue. It probably originated as a mere variation of one of those two colours, and may in fact represent the original hue of purpure, which is now treated as a much bluer colour than when it first appeared in heraldry. Although long shunned in the belief that it represented some dishonour on the part of the bearer, it has found some use in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Tenné or tenny, from Latin tannare, “to tan”, is the second of the so-called “stains”. It is most often depicted as orange, but sometimes as tawny yellow or brown. In earlier times it was occasionally used in continental heraldry, but in England largely confined to livery.

Furs

The use of heraldic furs alongside the metals and colours dates to the beginning of the art. In this earliest period, there were only two furs, ermine and vair. Ermine represents the fur of the stoat, a type of weasel, in its white winter coat, when it is called an ermine. Vair represents the winter coat of the red squirrel, which is blue-grey above and white below. These furs were commonly used to line the cloaks and robes of the nobility. Both ermine and vair give the appearance of being a combination of metal and colour, but in heraldic convention they are considered a separate class of tincture that is neither metal nor colour. Over time, several variations of ermine and vair have appeared, together with three additional furs typically encountered in continental heraldry, known as plumeté, papelonné, and kürsch, the origins of which are more mysterious, but which probably began as variations of vair.

Ermine

Ermine (Fr. hermine, Ger. hermelin) is normally depicted as a white field powdered with black spots, known as “ermine spots”, representing the ermine’s black tail. The use of white instead of silver is normal, even when silver is available, since this is how the fur naturally appears; but occasionally silver is used to depict ermine. There is considerable variation in the shape of ermine spots; in the oldest depictions, they were drawn realistically, as long, tapering points; in modern times they are typically drawn as arrowheads, usually topped by three small dots.

Vair

Vair (Ger. Feh) derives its name from Latin varius, “variegated”. It is usually depicted as a series of alternating shapes, conventionally known as panes or “vair bells”, of argent and azure, arranged in horizontal rows, so that the panes of one tincture form the upper part of the row, while those of the opposite tincture are on the bottom. Succeeding rows are staggered, so that the bases of the panes making up each row are opposite those of the other tincture in the rows above and below. As with ermine, the argent panes may be depicted as either white or silver; silver is used more often with vair than with ermine, but the natural fur is white.

When the pattern of vair is used with other colours, the field is termed vairé or vairy of the tinctures used. Normally vairé consists of one metal and one colour, although ermine or one of its variants is sometimes used, with an ermine spot appearing in each pane of that tincture. Vairé of four colours (Ger. Buntfeh, “gay-coloured” or “checked vair”) is also known, usually consisting of two metals and two colours.

Several variant shapes exist, of which the most common is known as potent (Ger. Sturzkrückenfeh, “upside-down crutch vair”). In this form, the familiar “vair bell” is replaced by a T-shaped figure, known as a “potent” due to its resemblance to a crutch. Other furs sometimes encountered in continental heraldry, which are thought to be derived from vair, include plumeté or plumetty and papelonné or papellony. In plumeté, the panes are depicted as feathers; in papelonné they are depicted as scales, resembling those of a butterfly’s wings (whence the name is derived). These can be modified with the color, arrangement, and size variants of vair, though those variants are much less common. In German heraldry there is also a fur known as Kürsch, or “vair bellies”, consisting of panes depicted hairy and brown. Here the phrase “vair bellies” may be a misnomer, as the belly of the red squirrel is always white, although its summer coat is indeed reddish brown.

-

Kürsch

Other tinctures

Several other tinctures are occasionally encountered, usually in continental heraldry:

- Cendrée, or “ash-colour”;

- Brunâtre (Ger. Braun), or brown, occasionally used in German heraldry, in place of purpure;

- Bleu-céleste or bleu de ciel, a sky blue colour intended to be lighter than azure;

- Amaranth or columbine, a strong violet-red, found in at least one grant of arms to a Bohemian knight in 1701;

- Eisen-farbe, or iron-colour, found in German heraldry; and

- Carnation, often used in French heraldry as the colour of flesh.

The heraldic scholar A. C. Fox-Davies proposed that, in some circumstances, white should be considered a heraldic colour, distinct from argent. In a number of instances, a label or collar blazoned as “white” rather than “argent” appears on a supporter blazoned argent or or. The use of “white” in place of “argent” would be consistent with the practice of heraldic blazon that discourages repeating the name of a tincture in describing a coat of arms, but if it were merely intended as a synonym of “argent”, this placement would clearly violate the rule against placing metal on metal or colour on colour (see below). This difficulty is avoided if “white” is considered a colour in this particular instance, rather than a synonym of “argent”. This interpretation has neither been accepted nor refuted by any heraldic authority, but a counter-argument is that the labels are not intended to represent a heraldic tincture, but are in fact white labels proper.

Proper

A charge that is coloured as it naturally appears is blazoned proper (Fr. propre), or “the colour of nature”. Strictly speaking, proper is not a tincture in itself, and if, as is sometimes the case, a charge is meant to be depicted in particular colours that are not apparent from the word “proper” alone, they may be specified in whatever detail is necessary. Certain charges are considered “proper” when portrayed with particular colours, even though a range of different colours is found in nature; for instance, a popinjay proper is green, even though wild parrots occur in a variety of colours. In some cases, a charge depicted in a particular set of colours may be referred to as “proper”, even though it consists entirely of heraldic tinctures; a rose proper, whether red or white, is barbed vert and seeded or.

Blazon

In heraldry and heraldic vexillology, a blazon is a formal description of a coat of arms, flag or similar emblem, from which the reader can reconstruct the appropriate image. The verb to blazon means to create such a description. The visual depiction of a coat of arms or flag has traditionally had considerable latitude in design, but a verbal blazon specifies the essentially distinctive elements. A coat of arms or flag is therefore primarily defined not by a picture but rather by the wording of its blazon (though in modern usage flags are often additionally and more precisely defined using geometrical specifications). Blazon is also the specialized language in which a blazon is written, and, as a verb, the act of writing such a description. Blazonry is the art, craft or practice of creating a blazon. The language employed in blazonry has its own vocabulary, grammar and syntax, which becomes essential for comprehension when blazoning a complex coat of arms.

Other armorial objects and devices – such as badges, banners, and seals – may also be described in blazon.

The noun and verb blazon (referring to a verbal description) are not to be confused with the noun emblazonment, or the verb to emblazon, both of which relate to the graphic representation of a coat of arms or heraldic device.

Blazon is generally designed to eliminate ambiguity of interpretation, to be as concise as possible, and to avoid repetition and extraneous punctuation. English antiquarian Charles Boutell stated in 1864:

Heraldic language is most concise, and it is always minutely exact, definite, and explicit; all unnecessary words are omitted, and all repetitions are carefully avoided; and, at the same time, every detail is specified with absolute precision. The nomenclature is equally significant, and its aim is to combine definitive exactness with a brevity that is indeed laconic.

However, John Brooke-Little, Norroy and Ulster King of Arms, wrote in 1985: “Although there are certain conventions as to how arms shall be blazoned … many of the supposedly hard and fast rules laid down in heraldic manuals [including those by heralds] are often ignored.”

A given coat of arms may be drawn in many different ways, all considered equivalent and faithful to the blazon, just as the letter “A” may be printed in many different fonts while still being the same letter. For example, the shape of the escutcheon is almost always immaterial, with very limited exceptions.

The main conventions of blazon are as follows:

- Every blazon of a coat of arms begins by describing the field (background), with the first letter capitalised, followed by a comma “,”. In a majority of cases this is a single tincture; e.g. Azure (blue).

- If the field is complex, the variation is described, followed by the tinctures used; e.g. Chequy gules and argent (checkered red and white).

- If the shield is divided, the division is described, followed by the tinctures of the subfields, beginning with the dexter side (shield bearer’s right, but viewer’s left) of the chief (upper) edge; e.g. Party per pale argent and vert (dexter half silver, sinister half green), or Quarterly argent and gules (clockwise from viewer’s top left, i.e. dexter chief: white, red, white, red). In the case of a divided shield, it is common for the word “party” or “parted” to be omitted (e.g., Per pale argent and vert, a tree eradicated counterchanged).

- Some authorities prefer to capitalise the names of tinctures and charges, but this convention is far from universal. Where tinctures are not capitalised, an exception may be made for the metal Or, in order to avoid confusion with the English word “or”. Where space is at a premium, tincture names may be abbreviated: e.g., ar. for argent, gu. for gules, az. for azure, sa. for sable, and purp. for purpure.

- Following the description of the field, the principal ordinary or ordinaries and charge(s) are named, with their tincture(s); e.g., a bend or.

- The principal ordinary or charge is followed by any other charges placed on or around it. If a charge is a bird or a beast, its attitude is defined, followed by the creature’s tincture, followed by anything that may be differently coloured; e.g. An eagle displayed gules armed and wings charged with trefoils or (see the coat of arms of Brandenburg below).

- Counterchanged means that a charge which straddles a line of division is given the same tinctures as the divided field, but reversed (see the arms of Behnsdorf below).

- A quartered (composite) shield is blazoned one quarter (panel) at a time, proceeding by rows from chief (top) to base, and within each row from dexter (the right side of the bearer holding the shield) to sinister; in other words, from the viewer’s left to right.

- Following the description of the shield, any additional components of the achievement – such as crown/coronet, helmet, torse, mantling, crest, motto, supporters and compartment – are described in turn, using the same terminology and syntax.

- A convention often followed historically was to name a tincture explicitly only once within a given blazon. If the same tincture was found in different places within the arms, this was addressed either by ordering all elements of like tincture together prior to the tincture name (e.g., Argent, two chevrons and a canton gules); or by naming the tincture only at its first occurrence, and referring to it at subsequent occurrences obliquely, for example by use of the phrase “of the field” (e.g., Argent, two chevrons and on a canton gules a lion passant of the field); or by reference to its numerical place in the sequence of named tinctures (e.g., Argent, two chevrons and on a canton gules a lion passant of the first: in both these examples, the lion is argent). However, these conventions are now avoided by the College of Arms in London, and by most other formal granting bodies, as they may introduce ambiguity to complex blazons.

- It is common to print all heraldic blazons in italic. Heraldry has its own vocabulary, word-order and punctuation, and presenting it in italics indicates to the reader the use of a quasi-foreign language.

-

Quarterly 1st and 4th Sable a lion rampant on a canton Argent a cross Gules; 2nd and 3rd quarterly Argent and Gules in the 2nd and 3rd quarters a fret Or overall on a bend Sable three escallops of the first and as an augmentation in chief an inescutcheon, Argent a cross Gules and thereon an inescutcheon Azure, three fleurs-de-lis Or. Arms of Churchill.

The Completed St Marys' de Pratis Force

I have finish my St Mary de Pratis, Leicester Abbey, force and I am blooming chuffed with it. I wanted a Militant Monk force because the Paul Hicks’ sculpts of the monks are so characterful and because because I thought it would be fun. Abbot William Pepyn is the commander and with the local lord’s knights to help protect the realm. What do you think of them?

The Mounted Arm of the Force

This is the last unit for my St Mary de Pratis force which in turn we led part of a larger force and these are the mounted knights. I have foot knight which are the backbone of the force, taking the centre with everything supporting them but the mounted knights are the hammer, the fast attack force, designed to sweep anyway all before these with there lance and armour. Well that is the theory.

I have painted these to be more lesser knights, lower order, loaned to the Abbey by their Baron/Lord protector. I love the way and feel of them and work well against the drab coloured monks.

Archers, Hunters or maybe Poachers

I’ve finished my archers for my St Mary de Pratis force and I wanted a civilian look, no “uniform” look for these as I seen them the foragers for the abbey. I think I have got the “look and feel” right and I cannot wait to paint so more missile troops for this game.

What do you think?

The Barons’ Responsibilities

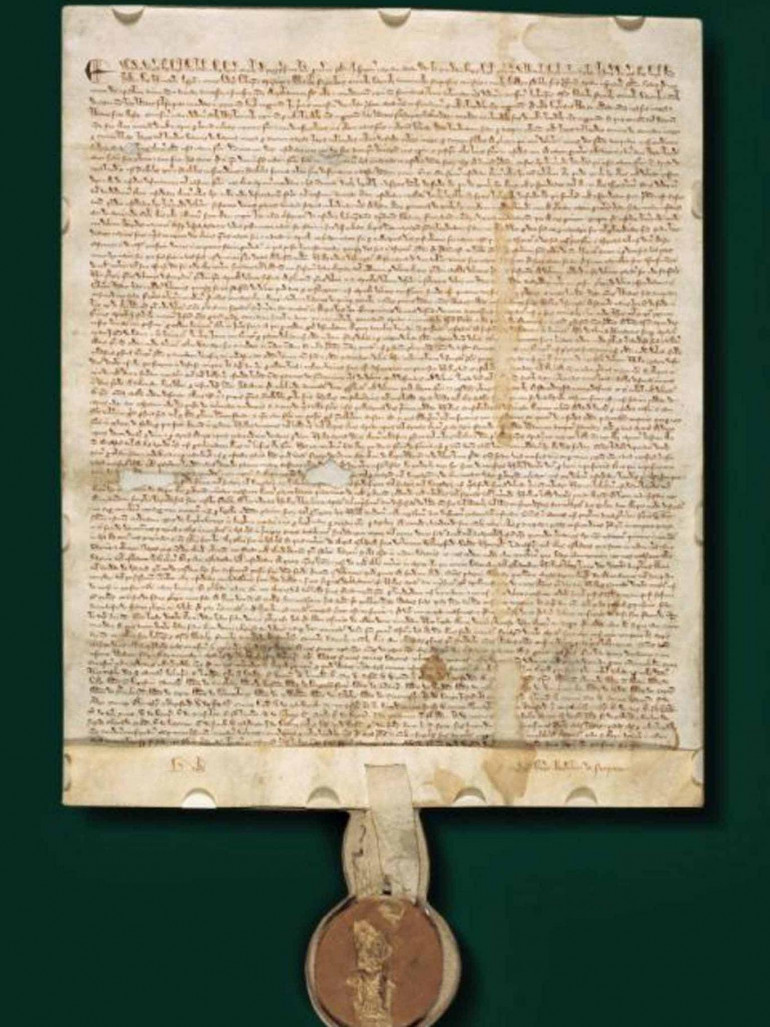

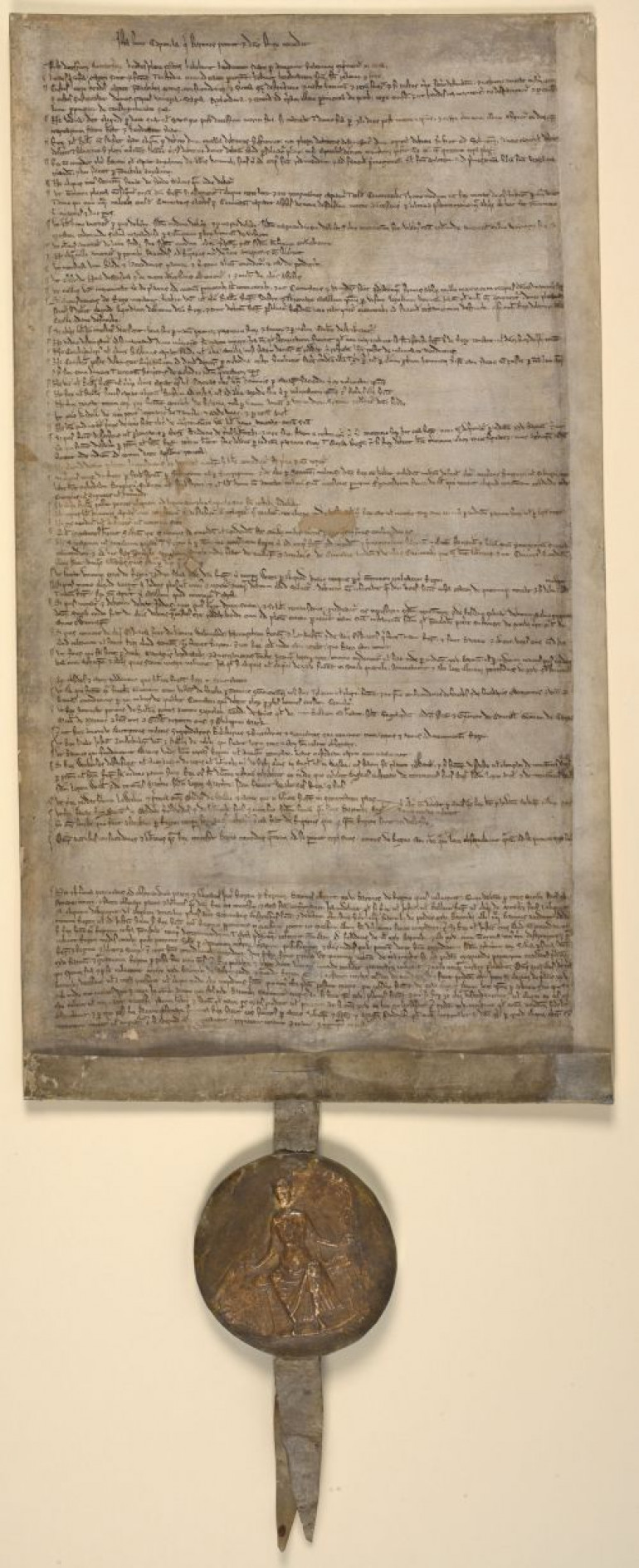

Clause 61 of Magna Carta

Since, moreover, for God and the amendment of our kingdom and for the better allaying of the quarrel that has arisen between us and our barons, we have granted all these concessions, desirous that they should enjoy them in complete and firm endurance forever, we give and grant to them the underwritten security, namely, that the barons choose five-and-twenty barons of the kingdom, whomsoever they will, who shall be bound with all their might, to observe and hold, and cause to be observed, the peace and liberties we have granted and confirmed to them by this our present Charter, so that if we, or our justiciar, or our bailiffs or any one of our officers, shall in anything be at fault toward anyone, or shall have broken any one of the articles of the peace or of this security, and the offence be notified to four barons of the foresaid five-and-twenty, the said four barons shall repair to us (or our justiciar, if we are out of the realm) and, laying the transgression before us, petition to have that transgression redressed without delay. And if we shall not have corrected the transgression (or, in the event of our being out of the realm, if our justiciar shall not have corrected it) within forty days, reckoning from the time it has been intimated to us (or to our justiciar, if we should be out of the realm), the four barons aforesaid shall refer that matter to the rest of the five-and-twenty barons, and those five-and-twenty barons shall, together with the community of the whole land, distrain and distress us in all possible ways, namely, by seizing our castles, lands, possessions, and in any other way they can, until redress has been obtained as they deem fit, saving harmless our own person, and the persons of our queen and children; and when redress has been obtained, they shall resume their old relations towards us.

And let whoever in the country desires it, swear to obey the orders of the said five-and-twenty barons for the execution of all the aforesaid matters, and along with them, to molest us to the utmost of his power; and we publicly and freely grant leave to everyone who wishes to swear, and we shall never forbid anyone to swear. All those, moreover, in the land who of themselves and of their own judgment, and he shall be sworn in the same way as the others. Further, in all matters, the execution of which is entrusted to these twenty-five barons, if perchance these twenty-five are present and disagree about anything, or if some of them, after being summoned, are unwilling or unable to be present, that which the majority of those present ordain or command shall be held as fixed and established, exactly as if the whole twenty-five had concurred in this; and the said twenty-five shall swear that they will faithfully observe all that is aforesaid, and cause it to be observed with all their might. And we shall procure nothing from anyone, directly or indirectly, whereby any part of these concessions and liberties might be revoked or diminished; and if any such thing has been procured, let it be void and null, and we shall never use it personally or by another.

The Articles of the Barons

The Articles of the Barons - The Magna Carta

1 After the death of their predecessors, heirs of full age are to have their inheritance by the ancient relief to be set out in the charter.

2 Heirs who are under age and in wardship are when they come of age to have their inheritance without relief or fine.

3 The guardian of an heir’s land is to take reasonable issues, customs and services, without destruction and waste of his men and goods, and if the guardian of the land inflicts destruction and waste, he is to lose the wardship. And the guardian is to maintain buildings, parks, fishponds, pools, mills and other things pertaining to that land, out of the issues of the same. And heirs are to be so married that they are not disparaged, and this by the counsel of their near kinsmen.

4 No widow is to give anything for her dower or marriage portion after the death of her husband, but she may remain in his house for forty days after his death, and her dower is to be assigned to her within that period; and she is to have her marriage portion and her inheritance immediately.

5 Neither the king nor his bailiff are to seize any land for debt while the debtor’s chattels suffice; nor are the debtor’s pledges to be distrained, while the principal debtor has enough to make payment; if indeed the principal debtor defaults on his payment, the pledges are, if they wish, to have the debtor’s lands until the debt is fully paid, unless the principal debtor can show that he is quit with regard to the pledges.

6 The king is not to grant to any baron the right to take an aid from his free men, except to ransom his person, to knight his first-born son, and to marry, once, his first-born daughter, and he is to do this by way of a reasonable aid.

7 No-one is to do more service for a knight’s fee than is owed for it.

8 Common pleas are not to follow the king’s court, but are to be appointed to some fixed place. And recognitions are to be held in the same counties, in this manner: the king is to send two justices four times in the year, who with four knights of the same county, chosen by the county court, are to take assizes of novel Disseisin, Mort d’Ancestor and Darrein presentment, nor is anyone to be summoned on account of this except the jurors and the two parties.

9 A free man is to be amerced for a small offence in proportion to the nature of the offence, and for a great offence in accordance with its magnitude, saving to him his livelihood; the villain is also to be amerced in the same way, saving to him his crops under cultivation; and the merchant in the same way, saving to him his stock in trade, by oath of trustworthy men of the vicinity.

10 A cleric is to be amerced in respect of his lay fee in the same manner as the aforesaid, and without regard to his ecclesiastical benefice.

11 No township is to be amerced for making bridges over rivers, unless they used rightfully to be there of old.

12 The measure of corn and wine, and the widths of cloths and other things, are to be reformed; and weights likewise.

13 Assizes of novel Disseisin and Mort d’Ancestor are to be expedited, and other assizes likewise.

14 No sheriff is to involve himself in pleas pertaining to the crown without the coroners; and counties and hundreds are to be at their old farms without any increment, except for the king’s demesne manors.

15 If anyone holding from the king dies, it is to be lawful for the sheriff or other royal bailiff to seize and record his chattels by the view of law-abiding men, as long as none of them are removed, until it is more fully known whether he owes any clear debt to the king; and then when the debt to the king is paid. the residue is to be relinquished to the executors to perform the testament of the deceased; and if nothing is owing to the king then all the chattels are to go to the deceased.

16 If any free man dies intestate, his goods are to be distributed by the hand of his nearest kinsmen on both sides of his family, under the supervision of the church.

17 Widows are not to be distrained to marry, when they wish to live without a husband, as long as they give security that they will not marry without the consent of the king, if they hold of him, or the consent of their lords of whom they hold.

18 No constable or other bailiff is to take corn or other chattels, unless he pays cash for them immediately, (or) unless he has respite with the consent of the seller.

19 No constable is to distrain any knight to give money instead of castle-guard, if he is willing to perform that guard in person or, if he is unable to do it for a satisfactory reason, through another reliable man; and if the king takes him in the army, he is to be quit of castle-guard in proportion to the amount of time [away].

20 No sheriff or royal bailiff, or anyone else, is to take any free man’s horses or carts for transporting things, except with his consent.

21 Neither the king nor his bailiff is to take another man’s wood to his castles or on other of his business, except with the consent of the person whose wood it is.

22 The king is not to hold the land of those who have been convicted of felony except for a year and a day, and then it is to be surrendered to the lord of the fee.

23 All fish-weirs are in future to be entirely removed from the Thames and Medway, and throughout the whole of England.

24 The writ called praecipe is not in future to be issued to anyone for any tenement in respect of which a free man could lose his court.

25 If anyone has been disseised or dispossessed without judgment by the king of lands, liberties and his right, it is to be restored to him immediately; and if a dispute arises about this, it is to be settled by judgment of the twenty-five barons; and those who were disseised by the king’s father or brother are to have their right without delay by judgment of their peers in the king’s court; and the archbishop and bishops are to deliver judgment at a specific day, without the possibility of an appeal, as to whether the king ought to have the term [of exemption] of other crusaders.

26 Nothing is to be given for a writ for an inquest concerning life or members, but it is to be granted without payment and not denied.

27 If anyone holds of the king by fee-farm, socage or burgage, and of someone else by knight service, the king is not to have the wardship of the knights of another man’s fee by reason of the burgage or socage, nor is he to have the wardship of the burgage, socage or fee-farm. And no free man is to lose his knights by reason of petty serjeanties, like those who hold a tenement by rendering knives or arrows or suchlike.

28 No bailiff is to put anyone to law by his accusation alone, without trustworthy witnesses.

29 The body of a free man is not to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way ruined, nor is the king to go against him or send forcibly against him, except by judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

30 Right is not to be sold or delayed or withheld.

31 Merchants are to have safe conduct to go and come to buy and sell, without any evil exactions but paying only the old and rightful customs.

32 No scutage or aid is to be imposed in the kingdom except by the common counsel of the kingdom, unless for ransoming the person of the king, and knighting his first-born son, and marrying, once, his first-born daughter, and for this a reasonable aid is to be taken. Tollages and aids on the city of London, and on other cities which have such liberties, are to be taken in like manner. And the city of London is to have in full its ancient liberties and free customs, both by water and by land.

32 No scutage or aid is to be imposed in the kingdom except by the common counsel of the kingdom, unless for ransoming the person of the king, and knighting his first-born son, and marrying, once, his first-born daughter, and for this a reasonable aid is to be taken. Tollages and aids on the city of London, and on other cities which have such liberties, are to be taken in like manner. And the city of London is to have in full its ancient liberties and free customs, both by water and by land.

33 It is to be lawful for each man to leave the kingdom and return to it, saving his allegiance to the king, except in time of war for some short time, for the sake of the common utility of the kingdom.

34 If anyone has taken a loan from Jews, great or small, and dies before the debt is paid, the debt is not to incur interest as long as the heir is under age, whoever he may hold from. And if the debt falls into the hand of the king, he is to take only the principal recorded in the charter.

35 If anyone dies and is indebted to Jews, let his wife have her dower. And if there are surviving children, let their needs be met from the property, and let the debt be paid from the residue, saving the service of the lords. And let other debts be dealt with in like manner. And let the keeper of the land surrender to the heir, when he comes of age, his land stocked with what the issues of the land can reasonably provide by way of ploughs and other necessary implements.

36 If anyone holds of an escheat, as of the honour(s) of Wallingford, Nottingham, Boulogne and Lancaster, or of other escheats which are in the king’s hand and are baronies, and dies, his heir will not give a relief or perform any service to the king other than he would to the baron; and the king is to hold it in the same manner in which the baron held it.

37 Fines made for dowers, marriages, inheritances and amercements, unjustly and against the law of the land, are to be entirely remitted; or they are to be dealt with by judgment of the twenty-five barons, or by judgment of the greater part of them, together with the archbishop and others whom he wishes to convoke to act with him. On condition that if any or some of the twenty-five are in such an action, they are to be removed and others substituted in their place by the rest of the twenty-five.

38 Hostages and bonds which were surrendered to the king as security are to be restored.

39 Those who have been outside the forest are not to come before the forest justices on the grounds of common summonses, unless they are involved in pleadings or [are] pledges. And the evil customs of forests and foresters, of warrens, and sheriffs, and rivers, are to be put right by twelve knights of each county, who should be chosen by the good men of that county.

40 Let the king remove entirely from office the kinsmen and whole brood of Gerard d’Athée, so that they may not hold office in future: namely, Engelard, Andrew, Peter and Guy de Chanceaux, Guy de Cigogné, Matthew de Martigny and his brothers; and his nephew Geoffrey, and Philip Mark.

41 And let the king remove the foreign knights, mercenaries, crossbowmen, routiers and serjeants who come with horses and arms to the detriment of the realm.

42 And let the king make justices, constables, sheriffs and bailiffs from those who know the law of the land and are willing to keep it well.

43 Let barons who have founded abbeys, for which they have royal charters or ancient tenure, have the custody of them when they are vacant.

44 If the king has disseised or dispossessed Welshmen of their lands, liberties or anything else in England or in Wales, they are to be given back to them immediately, without any legal proceedings. And if they were disseised or dispossessed of their English tenements by the king’s father or brother without judgment of their peers, the king will without delay do them justice, in the same way that he is to do justice to Englishmen, for tenements in England according to the law of England, for tenements in Wales according to the law of Wales, and for tenements in the march according to the law of the march. Let the Welsh do the same for the king and his men.

45 Let the king give back the son of Llywelyn, and also other hostages from Wales, and the bonds which were handed over to him as security for peace, unless things should be otherwise under the charters which the king has, by judgment of the archbishop and such others as he wishes to convoke to act with him.

46 Let the king deal with the king of Scots for the returning of hostages, and over his liberties and right, in accordance with the terms he comes to with the barons of England, unless it should be otherwise under the charters which the king has, by judgment of the archbishop and such others as he wishes to convoke to act with him.

47 And all the forests which have been afforested by the king during his reign are to be disafforested, and let the same be done with regard to the rivers which are game reserves by this king’s doing.

48 What is more, all these customs and liberties which the king has granted to the realm, to be observed on his own account with regard to his own men, all the men of the realm, both clergy and laity, will observe on their own account with regard to their own men.

Battles of Magna Carta, Part Four

1216-17: THE SIEGE OF DOVER CASTLE

Another epic and desperate siege of the castle by Prince Louis of France, and said to be the most momentous in all English history. The French king supported the unruly barons by sending his son and large forces. All aspects of siege warfare were employed and ultimately failed. Siege engines, mining and even bribery did not succeed, though the French did capture the barbican and undermined the gatehouse. The defenders rebuilt barricades and beat back the French.

1216-17: SANDWICH (LANDING AND NAVAL BATTLE)

King John called upon the naval resources of the Cinque Ports (Hastings, Rye, Hythe, Romney and Sandwich) which provided 50 ships, and had another 50 built. (In 1213, Philip II had gathered a fleet to invade England with papal blessing against the excommunicated John. The allies surprised the French fleet at anchor, capturing 300 vessels, and burning 100 more!) The royalist naval victory of 1217 meant that the war was finally over. A month later, the Treaty of Lambeth ensured that Prince Louis and his men left England, never to return.

1217: LINCOLN (SIEGE AND BATTLE)

Lincoln town was pro-rebel, but the castle held by Lady Nichola de la Haye was a pro-John castellaine. In May 1217, French forces besieging the castle were routed by a relieving force under William Marshal (Earl of Pembroke). The town was thoroughly sacked and its goods carried off by the victors earning the nickname ‘Lincoln Fair’.

1224: THE SIEGE OF BEDFORD

Henry III besieged the Bedford Castle in 1224 after a falling out with Falkes de Breauté. It involved an army of 2,700 soldiers. The siege of the mighty castle lasted from 20 June until 15 August and was one of the longest sieges of the century, rivalled only by those of Dover (July 1216 – May 1217) and Kenilworth (May to December 1266). It began with a move led by Hubert de Burgh to bring back under royal control all royal castles entrusted to the adherents of King John. It was the last outburst of violence which had begun at the end of King John’s reign but the firm action taken by the sixteen year old Henry III to capture the castle ensured that with the exception of the revolt of Richard Marshal in 1233, England was not riven by civil war for another forty years. It was another milestone in the flowering of a growing sense of Englishness.

Battles of Magna Carta, Part Three

1216: THE SIEGE OF WINDSOR

After granting Magna Carta at Runnymede, the king retired to Windsor from the capital, which was soon afterwards occupied by the barons. Hostilities, however, soon broke out again; the barons abjured their allegiance and sought help from France. The invasion of England by Louis of France, which began in May 1216, was followed by the siege of Windsor Castle. The castle was held for the king by Fawkes de Breauté, one of John’s unsavoury advisors, who had filled the castle with foreign mercenaries. The siege lasted from June to September, when it was raised, and on the death of the king in October it was still in the hands of his adherents.

1216: THE SIEGE OF BERWICK CASTLE

In the northern reaches, King John arrived in 1216 to storm the fortified town of Berwick. On the river Tweed, it stood close to the borders of England and Scotland. The castle was founded in the 12th century by the Scottish King David I.

1216: THE SIEGE OF BARNARD CASTLE

The 1216 siege of Barnard Castle in Durham was successfully resisted for King John by Hugh de Baliol against invading Scots. Leading rebel and Magna Carta surety Eustace de Vesci was shot dead by a crossbowman during the siege. The influence of the family enabled John Baliol, with the help of Edward I, to be crowned King of Scotland.

1216: THE SIEGE OF BERKHAMSTED CASTLE

In December 1216, Berkhamsted Castle was besieged by Prince Louis of France. It is likely that the constable at the castle was aware of the approach of a hostile force of French mercenaries. He will have hastily arranged for plentiful food supplies to be brought in: bread, cheese, eggs and meat. Hopefully, he would have sent women and children out of harm’s way, if only to preserve the food and drink supplies for fighting men. Wells in the bailey and on the motte provided plentiful water and they would have hunkered down, ready for the attack.

After twenty days of siege, the garrison within surrendered. Next year, the year following the death of King John, the castle was reclaimed by Royalists.