PanzerKaput Goes To Barons’ War

Recommendations: 11332

About the Project

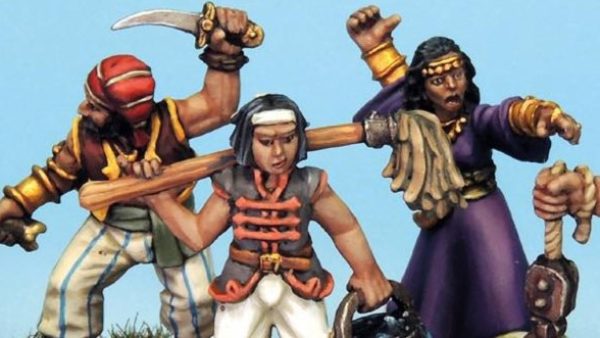

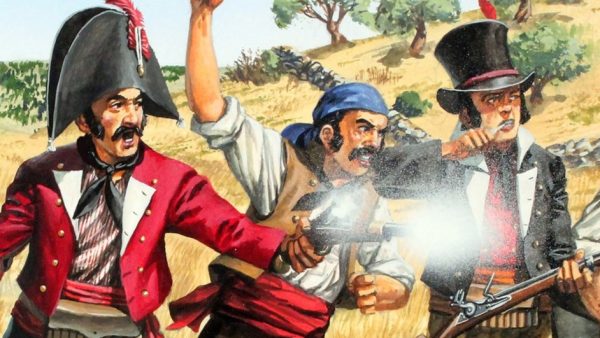

Set against a backdrop of a Civil War that lasted for two years, 1215-17, as a result of the issuing of Magna Carta. A civil war was the perfect opportunity for the leading nobles of the time to grab land and power while settling some old scores along the way. This vying for land and power hadn't stopped since the invasion of 1066 with only the strongest of kings being able to keep their nobles in check. Our narrative focuses on small groups of warriors brought together under a lord or baron to raid and steal or defend land and property. With the strong, wise, cunning and lucky aiming to rise out of this civil strife in a better position than when it started. The Barons' War skirmish game has been written to enable players to fight out tabletop battles against the backdrop of the First Barons’ War between rival Barons or rival factions who find themselves on either side of the conflict. The game is historically themed, the gameplay is fast-paced and tactical with plenty of narrative and where force building presents you with lots of options enabling two players to muster very different retinues. However, as intended, this is an alpha set of rules which does not include rules for siege warfare, although rules for fighting in buildings are included. Campaign rules are something that will be addressed at a later date and released online. Having grown out of the Barons’ War Kickstarter project, the intention is for this ruleset to develop into a system that could be used throughout the Medieval period. Starting with England from when the Western Roman Empire withdrew around 410 AD to 1485 AD when Richard III died at the Battle of Bosworth Field. This presents us with a huge span of history for gaming which can be broadly divided into Romano-British, Anglo-Saxon and Viking, Anglo-Norman, Angevin and Plantagenet. And that’s just when looking at it from Great Britain. With warriors of this period being pretty similar, it would be easy to use the profiles in this rulebook to play out tabletop battles in any setting. Over time we see these rules evolving with additional warriors, characters, abilities and scenarios being added starting with the Dark Ages, the Anarchy and the Crusades and shared to www.warhost.online, which has been set up to be the community website for the game.

Related Game: The Barons' War

Related Company: Footsore Miniatures and Games

Related Genre: Historical

This Project is Active

New Barons War Video uploaded to YouTube

I have uploaded a new video about my The Barons’ War: A Medieval Skirmish Game project.

I hope you enjoy the video and if you can please click Like and Subscribe.

I am running a game at Partizan 2022, on Sunday 22nd May. Free you are going please come on over have a look at the game and say Hi

Thanks

Some More Local Knights, Sir John Hazelrigge, Sir Thomas Paget & Sir Edward Pochin

I have finished the special character figures from The Barons’ War range from Footsore, them being Guillaume II des Barres and William Marshal from the Gutted at Gaillard – Character Set.

But I have painted them as two local knights, Sir John Hazelrigge, in the green and white and Sir Thomas Paget in the blue and yellow. Also I have painted the monthly special figure, William of Ypres as Sir Edward Pochin of Barkby, with the red shield.

I have really enjoyed painting these and have finished all the Barons’ War figures I have, for the time being, but next is the Welsh for the Barons’ War. #thebaronswar #warhost #fsinspired

New Video Uploaded to YouTube, Barricades and Ruins

I have uploaded a new The Barons’ War: A Medieval Skirmish Game video to my YouTube Channel.

This time the video is about the newly painted Ruined Hovels and Barricades from Warhost via Footsore Miniatures & Games

I hope you enjoy it

More Terrain for Barons' War, Ruined Hovels and Barricades

I have finished the ruined hovels and barricades from Footsore’s Barons’ War range and I am very pleased with them. They are beautifully detailed and have so many points of interest that they are a dream to paint. It is nice to see a set of ruined buildings, that are the same buildings that Footsore do, as it means you can have some creative scenarios where you destroy the buildings during the game and replace them with these. All in all very nice and I love them.

These are very useful not just for the Barons’ War but also for other periods, games and settings too like Moonstone, Burrows and Badgers, Border Reivers, Late Medieval, Blood and Plunder, Donnybrook, etc. I cannot wait to get these on the table for Partizan 2022 at the Newark Showground, UK on 22/05/22 as I think they will finish the table off well.

How I painted the wood effect I used Vallejo Model Colour German Grey as the base, then drybrush of VMC German Camo Mid Brown, I lighter drybrush of VMC Medium Grey and a lighter still drybrush of VMC Pale Sand. Then I washed VMC German Grey over it.

Lord Hugh de Bonneville 500 point Force for Wednesday Game

Here is my opponent for Wednesday’s game, Lord ‘Hugh de Bonneville. The Bishop, Julien Felagh, has sent his best man from the abbey near Downton with a message, it appears you owe money to the church…

Retinue points: 503 / 500

95 points – 3 warriors

1x Mounted Lord Regular, Lord Hugh de Bonneville

Equipped

Sword, Mail, Barded Horse, Pennant, Priest

Abilities

Chivalry, Live By The Sword, Commander, Inspire

2x Mounted Knights Irregular

Equipped

Sword, Mail, Medium Shield, Barded Horse

Abilities

Chivalry

80 points – 4 warriors

4x Foot Knights Irregular

Equipped

Sword, Mail, Medium Shield

Abilities

Chivalry

96 points – 6 warriors

6x Foot Sergeants Irregular

Equipped

Falchion, Padded

Abilities

Martial Respect

152 points – 8 warriors

8x Bowmen Veteran

Equipped

Bow

Abilities

Every Bloody Sunday

80 points – 8 warriors

8x Levy Green

Equipped

Spear

Abilities

Sorry M Lord

Border Reivers, The Border Wars, Finished

I have finished my Border Reivers from Flags of War for their up and coming Border Wars range and I am very pleased with the results. Lovely sculpts, full of character and scream the period, they paint up so nicely. Very pleased with them indeed.

The building from Fogou Models and Footsore

Sir Robert Hotoft 500 points Force for Wednesday Game

I have another game of Barons’ War on Wednesday and I am fielding a force that it led by a fight that is buried in the local church of St Mary’s Sir Richard Hotoft of Humerstane. He was alive or even born when the Baron’s War was but I wanted a local link.

All thats know about him and the family is as followings

The Hotoft family had been settled at Humberstone from before 1288 and had since then acquired property near the High Cross in Leicester (about two miles away) as well as land at Hathern and Shepshed in the north of the county. In 1375, at the time of the death of his father, then a coroner of Leicestershire, Richard was a minor; and his marriage was then claimed by John, Lord Grey of Codnor, who alleged that the boy’s mother and brother-in-law, John Folville of Rearsby, had taken him away from Humberstone contrary to his wishes. He may have come of age by Michaelmas 1388 when the overlord of Humberstone, John, duke of Lancaster, brought an action against him in the court of common pleas for a debt of 58s; but even so his career did not properly begin until after the accession of Lancaster’s grandson as Henry V.

Hotoft attended the Leicestershire elections to the first Parliament of the reign, secured election himself in the autumn of 1414, and served for nearly four years on the local bench. In 1416 Thomas Ashby of Quenby named him as an executor of his will, at the same time making a bequest of 20 marks to his younger son, Thomas, but following a disagreement between Hotoft and his fellow executors over the administration of Ashby’s estate, the bishop of Lincoln appointed the archdeacon of Leicester as receiver of the deceased’s effects. This did not prevent Bartholomew Brokesby from suing Hotoft for a debt of £100 incurred by his late friend. Another lawsuit was instigated by Hotoft himself in 1420 against the master of St. John’s hospital, Leicester, for alleged breach of an agreement made by a former master with the MP’s kinsman, Richard Witeby, concerning the foundation of a chantry.

Under Henry VI Hotoft attended the Leicestershire parliamentary elections of 1423 and 1427, served a term as escheator and, described as ‘the elder’, performed his last duties as a royal commissioner in the spring of 1431. By that time his son, Richard, was well established in his career as a lawyer, and it had probably been he who, as ‘of Leicestershire, gentleman’, had provided securities in the Exchequer in 1429 on behalf of John Brome† of Warwickshire. The young man proved to be of higher calibre than his father: he rose to be feodary of the honour of Leicester, duchy of Lancaster bailiff of Leicester, councillor to Humphrey, duke of Buckingham, and Member of eight Parliaments between 1437 and 1455. In the 1470s, following the deaths of that Richard Hotoft and his brother Thomas, their property was claimed by the descendants of our shire knight’s sister, Iseult Folville.

Retinue points: 500 / 500

174 points – 6 warriors

1x Lord Regular, Sir Richard Hotoft

Equipped

Sword, Mail, Pennant

Abilities

Chivalry, Live By The Sword, Commander, Inspire, Heroic

5x Foot Knights Regular

Equipped

Sword, Mail, Medium Shield

Abilities

Chivalry, Live By The Sword, Old-soldiers

92 points – 4 warriors

4x Foot Knights Regular

Equipped

Mace, Mail, Medium Shield

Abilities

Chivalry, Live By The Sword

70 points – 7 warriors

7x Levy Green

Equipped

Hand Weapon, Sling

Abilities

Sorry M Lord

100 points – 4 warriors

4x Foot Sergeants Regular

Equipped

Falchion, Mail, Medium Shield

Abilities

Martial Respect, Drilled

New Video about Plans for Partizan Show

New YouTube Video about Plans for The Barons’ War: A Medieval Skirmish Game at Partizan 2022, Newark Showground, UK

Hope you like it.

![Very Cool! Make Your Own Star Wars: Legion Imperial Agent & Officer | Review [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2025/12/Star-Wars-Imperial-Agent-_-Officer-coverimage-V3-225-127.jpg)