PanzerKaput Goes To Barons’ War

Recommendations: 11323

About the Project

Set against a backdrop of a Civil War that lasted for two years, 1215-17, as a result of the issuing of Magna Carta. A civil war was the perfect opportunity for the leading nobles of the time to grab land and power while settling some old scores along the way. This vying for land and power hadn't stopped since the invasion of 1066 with only the strongest of kings being able to keep their nobles in check. Our narrative focuses on small groups of warriors brought together under a lord or baron to raid and steal or defend land and property. With the strong, wise, cunning and lucky aiming to rise out of this civil strife in a better position than when it started. The Barons' War skirmish game has been written to enable players to fight out tabletop battles against the backdrop of the First Barons’ War between rival Barons or rival factions who find themselves on either side of the conflict. The game is historically themed, the gameplay is fast-paced and tactical with plenty of narrative and where force building presents you with lots of options enabling two players to muster very different retinues. However, as intended, this is an alpha set of rules which does not include rules for siege warfare, although rules for fighting in buildings are included. Campaign rules are something that will be addressed at a later date and released online. Having grown out of the Barons’ War Kickstarter project, the intention is for this ruleset to develop into a system that could be used throughout the Medieval period. Starting with England from when the Western Roman Empire withdrew around 410 AD to 1485 AD when Richard III died at the Battle of Bosworth Field. This presents us with a huge span of history for gaming which can be broadly divided into Romano-British, Anglo-Saxon and Viking, Anglo-Norman, Angevin and Plantagenet. And that’s just when looking at it from Great Britain. With warriors of this period being pretty similar, it would be easy to use the profiles in this rulebook to play out tabletop battles in any setting. Over time we see these rules evolving with additional warriors, characters, abilities and scenarios being added starting with the Dark Ages, the Anarchy and the Crusades and shared to www.warhost.online, which has been set up to be the community website for the game.

Related Game: The Barons' War

Related Company: Footsore Miniatures and Games

Related Genre: Historical

This Project is Active

Good Reveiw of the Rules from Warhost for Barons War

I very good YouTube review of the rules.

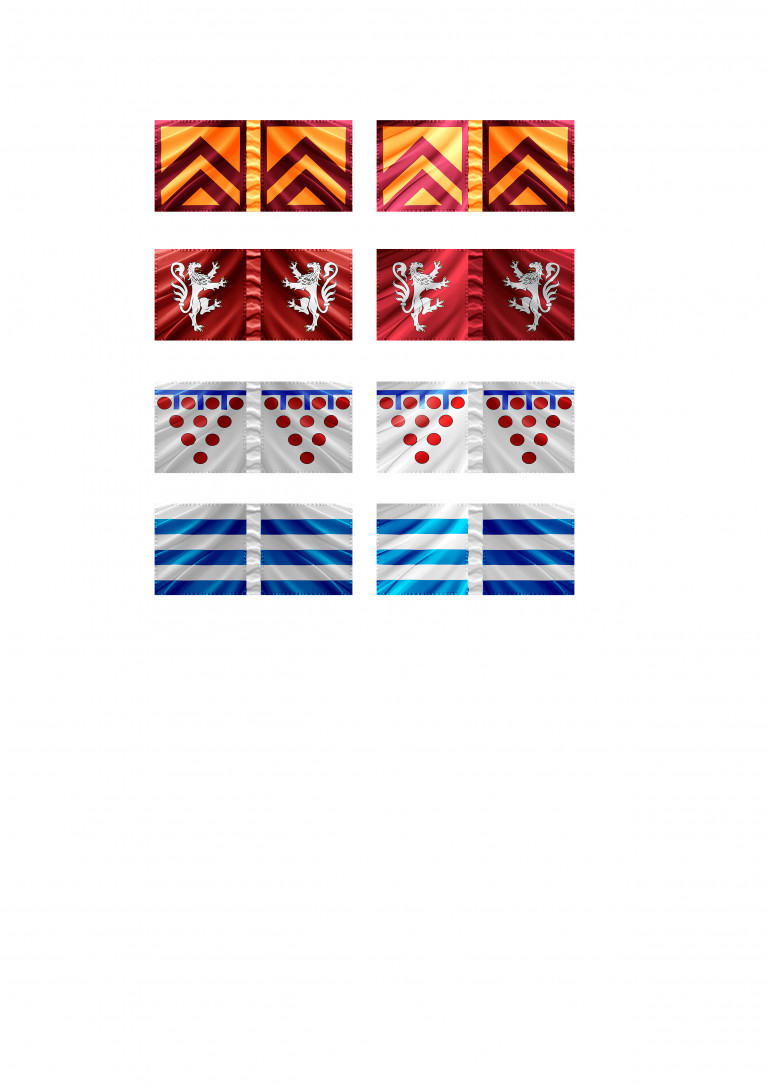

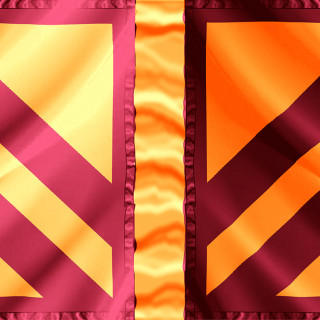

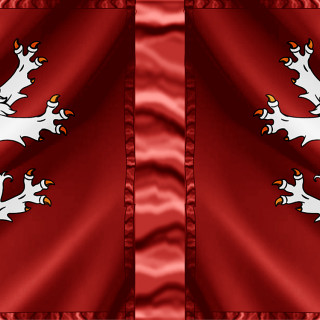

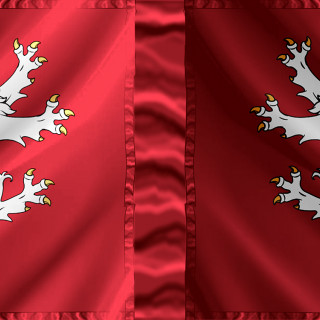

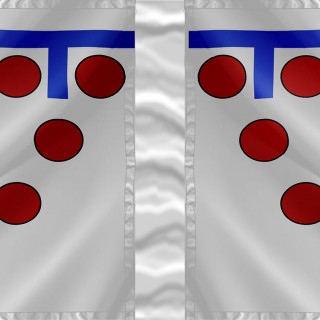

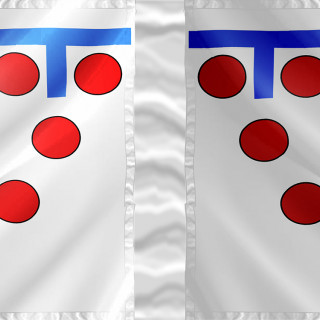

Banners for my Lords

I have working on banners and flags for my Lords to fit on their bannermen. I have based the banners on the heraldry of each of the Lords I have. I created the banners and the background patterns using Photoshop and I worked on the background pattern so that the one side is the opposite to the other to see if it looks more realistic.

So what do think did it work?

William d’Albini, Lord of Belvoir Castle

William de Mowbray

John Babington

Henri de Grey

Movement and Coherency Vid

Barons War vid on Movement and Coherency. Hopefully the first of many

The Siege of Northampton Castle

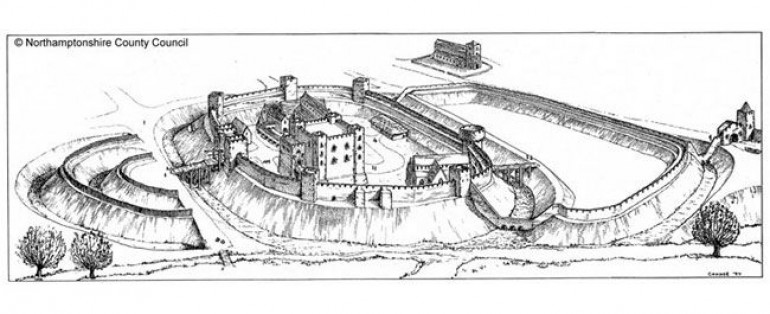

William the Conqueror made Simon de St. Liz the first Norman Earl of Northampton, and he is now well known in the town for building the Castle. It is more than likely there was some sort of Saxon or Danish fortification in place on the site prior to the building of the Castle. In addition to the Castle, St Liz built St. Andrew’s Priory, many parts of early Norman Northampton, and, after the first Crusade in 1099, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Sheep Street.

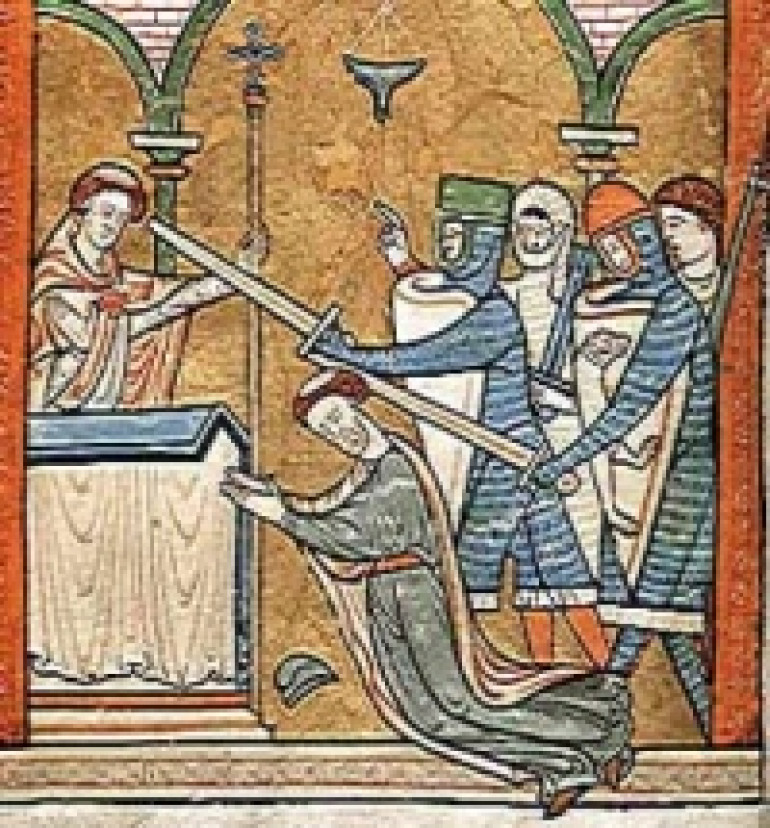

It is probably when St. Liz died that the Castle passed into the hands of King Henry I, who had previously held an important meeting at the Castle in 1106. The most famous event to occur at the Castle is surely the trial of Saint Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, which occurred in 1164 and was held by Henry I’s grandson Henry II and a Grand Council of Barons.

Becket himself probably lodged at nearby St. Andrew’s Priory and would certainly have visited St. Peter’s church too. His escape towards France under the cover of darkness is well known as is his subsequent murder at Canterbury Cathedral in 1170.

Another important historical figure associated with the Castle is King John (1199-1216) who spent all the feast days (Christmas, Easter and Whitsun) at Northampton and is known to have visited the Castle on no less than 30 occasions. Indeed he thought so much of Northampton that he moved the Royal Treasury to the Castle in 1205. The struggles against the Barons took place here in several Great Councils, leading to the Magna Carta in 1215.

In the civil wars between King John and his barons, the latter used it as a stronghold. When the King prevailed, the castle was entrusted to Falkes de Breauté, whom the King admired for his courage during the war. There was a second siege of Northampton Castle in 1215. It was broken by Flemish mercenaries sent by King John. When the king defeated the garrison, the castle reverted to the crown, but was later destined to be owned by the confederate barons.

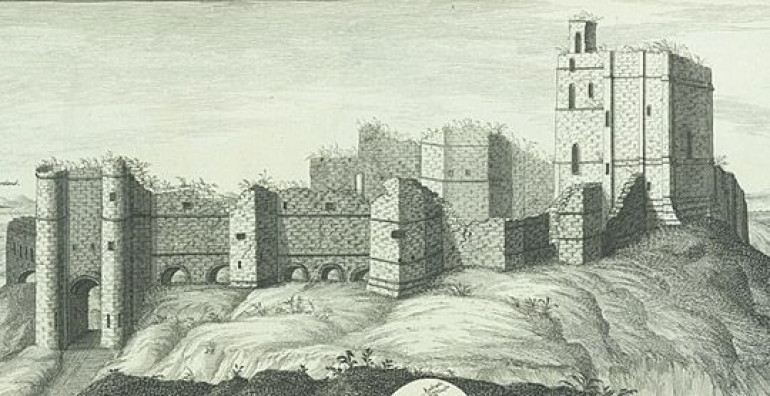

The Siege of Norham Castle

The castle was founded when Ranulf Flambard, Bishop of Durham from 1099 to 1128, gave orders for its construction in 1121, in order to protect the property of the bishopric in north Northumberland, from incursions by the Scots.

In 1136 David I of Scotland invaded Northumberland and captured the castle. It was soon handed back to the bishopric, but was captured again in 1138 during another invasion. This time, the structure of the castle was substantially damaged. It remained derelict until Hugh de Puiset, Bishop of Durham from 1153 to 1195, had the castle rebuilt. The work was probably directed by Richard of Wolviston, who was the bishop’s architect.

In 1174 Hugh de Puiset supported the rebels in a revolt against Henry II, during which the Scottish king, William the Lion invaded Northumberland. The rebels were defeated and as a result, Bishop Hugh was forced to relinquish Norham Castle to the crown. The castle was administered by a constable appointed by the crown and garrisoned by royal soldiers. This continued until 1197, two years after Hugh’s death, when it was restored to his successor, Philip of Poitou. The latter showed himself to be loyal to King John. When Philip died in 1208 the castle reverted to royal control.

In 1209 the castle accommodated both King John and William the Lion, on an occasion when William did homage for his English lands to the English king. Between 1208 and 1211, King John maintained the castle defences in good order and provided a strong garrison. The strong defences were needed in 1215, when Alexander II of Scotland, son of William the Lion, besieged the castle for forty days without success. In 1217 the castle was once again restored to the bishopric of Durham.

Edward I, known as “Hammer of the Scots”, visited the castle more than once. He did so in 1292 when John Balliol, King of Scotland did homage to him there. In 1296 Edward invaded Scotland, and during his campaign, his queen, Marguerite of France, remained at Norham Castle.

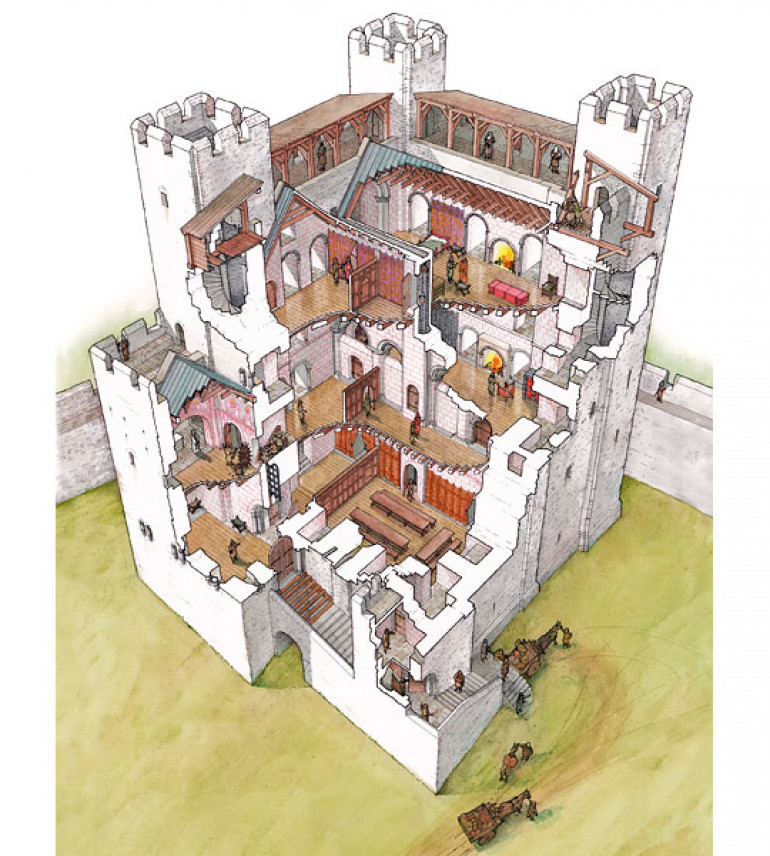

The castle stands on the south bank of the River Tweed, high above the river, so that the north side is protected by a steep slope. A deep ravine protected the east side and an artificial moat was dug round the west and south sides to complete the protection. The castle had an inner and outer ward. The inner ward stood on a mound and was separated from the outer ward by a moat, crossed by a drawbridge.

The main entrance to the castle was the strongly fortified West Gate leading into the outer ward. It was protected by a stone causeway spanned by a drawbridge and is also known as “Marmion’s Gate“. There was an additional gate to the south of the outer ward, known as the Sheep Gate.

The inner ward was entered by crossing a drawbridge across the moat and entering through a fortified gate on the west side. The drawbridge has now been replaced by a wooden bridge. On the north side of the inner ward was the bishop’s hall, measuring 60 ft by 30 ft (18.3m by 9.1m), now in ruins. To the east side of the inner ward stands the keep, measuring 84 ft by 60 ft (25.6m by 18.3m) and 88 feet (26.8 m) high. The keep is said to have been built by Hugh de Puiset.

Siege of Rochester Castle I

On 11 October 1215, a crack troop of a hundred knights arrived at the gates of Rochester Castle and demanded to be admitted. The constable of the castle, Sir Reginald de Cornhill, did not hesitate, for he had been expecting them. The drawbridge was lowered, the doors swung open, and the horsemen swept inside.

These men were rebels, come into Kent on a highly dangerous mission. Earlier in the year, along with scores of other noblemen, they had seized control of London in defiance of their king. In recent days, however, they had started to sense that the tide was turning against them, and had therefore decided to take action. Selected by their fellows as the bravest and most skilled in arms, they had ridden south-east to open up a second front. If London was to hold out, they knew they had to distract the king, and draw his fire away from the capital.

Their plan, in this respect, was brilliantly successful. Two days later, a royal army drew up outside the walls of Rochester. King John had arrived.

John was the youngest son of Henry II, and the runt of his father’s litter. He is familiar to all of us as the bad guy from the Robin Hood stories – the snivelling villain who betrayed his elder brother, ‘Good’ King Richard the Lionheart, and made a grab for the English throne. It will hardly surprise most people to learn that this picture of John is a caricature – the Robin Hood legends originated long after the king was dead. Nevertheless, even if we scrape off all the mud that has been flung at John over the centuries, he still emerges as a highly unpleasant individual, and a man unsuited to the business of ruling. Contemporaries might not have recognized the hideous, depraved monster of legend, but they would have acknowledged the basic truth of the matter – John was a Bad King.

To find out what people really thought about King John, we have to leave the stories of Robin Hood, and turn instead to another piece of writing, very different but no less famous. In 1215, shortly before they set off to seize Rochester Castle, John’s enemies compiled a list of complaints about him, and presented it to the king in the hope of persuading him to behave better in the future. The list was drawn up in the form of a charter and, because it was so long, the charter itself was very big. People soon started referring to it simply as the Big Charter; or, in Latin, Magna Carta.

So, by looking at Magna Carta, we can work out why people were annoyed with King John. What aggravated them most, it seems, was the way in which he constantly helped himself to their cash; the first clauses of the Charter are all concerned with limiting the king’s ability to extort money. In 1204, five years into his reign, John had suffered a major military and political disaster when he lost Normandy, Anjou and Poitou to the king of France. These provinces had formed the heart of John’s empire, and trying to get them back had kept him busy for the past ten years. Ultimately, however, by plotting his recovery, John was paving the way to his own downfall. The cost of building an alliance to strike back against the French king was enormous, especially because it was John’s misfortune to rule at a time when inflation was causing prices (of mercenaries, for example) to soar. With increasing frequency, John passed the costs on to his English subjects, imposing ever greater and more frequent taxes, fining them large sums of money for trivial offences, and demanding huge amounts of cash in return for nothing more than his grace and favour. Very quickly, John managed to create a situation where the people who didn’t want him in charge outnumbered those who did – a dangerous scenario for any political leader.

In some respects, however, the rebellion that the king faced in 1215 was not entirely his own fault. Both his father and his brother had governed England in much the same fashion, expanding their power at the expense of the power of their barons. One very visible way of measuring their success is by looking at their castles. At the start of Henry II’s reign in 1154, only around 20 per cent of all castles in the country were royal. The two decades before Henry’s accession had seen a proliferation of private castles (mostly motte and baileys) built without the king’s consent. One of Henry’s first actions as king was to order (and, where necessary, to compel) the destruction of such fortifications. Moreover, Henry and his sons, as we have seen, built new castles – big, impressive stone towers like Newcastle, Scarborough, Orford, and Odiham. By the time of John’s death, the ratio of royal castles to baronial ones had altered drastically; almost half the castles in England were in royal hands. Castles, therefore, provide a good index of the king’s power against the power of his barons.

It is evident that the rebels brought long-term grievances such as this to the negotiating table in 1215, because John tried to address them in Magna Carta.

‘If anyone has been dispossessed without legal judgement from his lands or his castles by us,’ the king said, ‘we will immediately restore them to him.’

But John went on to add that his subjects should make allowances for anyone who had been similarly dispossessed ‘by King Henry our father, or King Richard our brother’. Such hair-splitting, however, ignored the basic truth of the matter, which was that Henry and Richard were simply better kings than John. They were skilled warriors, while he was condemned for his cowardice. Although he proved a capable administrator (John could be dynamic and efficient when it came to collecting taxes), he was a bad manager, unfit to command the loyalties of his leading subjects, unable to check or channel their ambitions, and uneven in his distribution of rewards. Most of all, John was just an unpleasant guy. He sniggered when people talked to him. He didn’t keep his word. He was tight-fisted and untrusting. He even seduced the wives and daughters of some of his barons. Henry and Richard might have acted unfairly from time to time, but overall people liked them; almost nobody liked John.

It was John’s personality, in the end, that doomed Magna Carta to failure. There was little point in persuading John to make such an elaborate promise, because he was bound to try and wriggle out of it. Sure enough, no sooner had negotiations ended than the king was writing to the Pope, explaining how the Charter had been forced out of him, and asking for it to be condemned. By the time the Pope wrote back, however, John’s opponents had already worked out for themselves that Magna Carta was not worth the parchment it was written on. The king would never keep his promises, and they had no way of compelling him to do so. They too abandoned the Charter as a solution, in favour of the much simpler plan of offering John’s crown to someone else. By the autumn of that year, both the king and the rebels were openly preparing for war.

This war was eventually fought right across the country. The South-East of England, however, and especially Kent, was the most important arena of conflict, because both parties were seeking assistance from the Continent. The rebels, for their part, had decided to offer the crown of England to Prince Louis, eldest son of the king of France. They had already made overtures to him in the course of the summer, and were hoping he would soon arrive and stake his claim in person, bringing with him much-needed reinforcements. John, meanwhile, was also looking across the Channel for help, but in his case from Flemish mercenaries. The king had recently despatched his recruiting agents overseas, and was hovering anxiously on the south coast, trying to secure the loyalty of the Channel ports, and waiting for his soldiers of fortune to arrive.

In such circumstances, control of Rochester Castle, which stood at the point where the main road to London crossed the River Medway, became all-important. John understood this as well as anyone, and for this reason had been trying to get his hands on the castle since the start of May, when the rebellion against him had first raised its head. The king had already written to the Archbishop of Cantebury twice, asking, in the nicest possible way, if he would mind instructing his constable to surrender the great tower into the hands of royal representatives. Both times, however, the request fell on deaf ears. The archbishop was one of John’s leading critics and, realizing only too well what the king’s intentions were, had promptly done nothing. Likewise, there was no love lost between the king and Rochester’s constable, Sir Reginald de Cornhill. He was one of the hundreds who were heavily in debt to the Crown, and John had recently deprived him of his job as Sheriff of Kent. Cornhill’s response was probably more decisive; the likelihood is that he got a message through to the rebels in London, pledging his support, and expressing his willingness to help them.

When they realized that Rochester was theirs for the taking, the rebels in London formulated their plan. A detachment of knights would be sent to occupy the castle and hold it against John, and the man to lead it would be Sir William de Albini. Sir William is quite a dark horse: we don’t have a great deal of information about him. Of course, the fact that he was chosen (or volunteered) to lead the mission indicates that he must have been a skilled and respected warrior. One contemporary writer calls him ‘a man with strong spirit, and an expert in matters of war’. More puzzling is the fact that he does not seem to have had any of the personal grudges harboured by John’s other opponents. On the one hand, he was clearly one of the leaders of the rebellion: back in the summer he had been named as one of the twenty-five men who were to enforce Magna Carta. On the other hand, Albini only joined the other rebels a week before the Charter was drafted. Whatever his own motivation for taking up arms against his king, in the weeks that followed there was no doubt about the strength of his commitment to the rebel cause.

Albini and his companions arrived at Rochester on a Sunday. On entering the castle, they found to their alarm that the storerooms were badly provisioned. Not only were they short on weapons and ammunition; there was, more worryingly, an almost total lack of food. They quickly set about remedying the situation, plundering the city of Rochester for supplies. In the event, however, their foraging operation only lasted forty-eight hours. By Tuesday, John and his army were outside the castle gates.

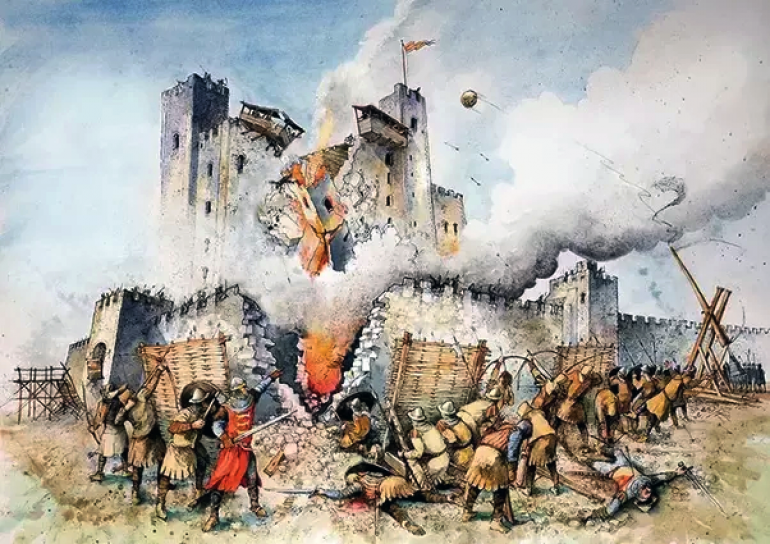

In such circumstances, we might not necessarily expect there to have been much of a fight. Just because one side in a dispute occupies a castle, and the other side turns up outside with an army, it does not automatically follow that a siege must take place. The defenders inside a castle might peer over their battlements at a colossal army, rapidly calculate the odds, and conclude that surrender is in their own best interests. Likewise, in many cases the prospective besieger will roll up with his army, assess the defences to be far too strong to break, and move on to take easier, softer targets. In this dispute, however, with each side playing for the highest stakes, and Rochester being so crucial to their respective plans, the king and his enemies exhibited an uncommon degree of determination. The rebels in the castle, in spite of their poor provisions, decided they were going to tighten their belts and stick it out. King John, pitching his camp outside the castle, looked up at the mighty walls of Rochester, and vowed he was going to break them. The scene was set for a monumental siege.

Ralph of Coggeshall, provides us with an account of the preliminary encounter between John and the rebels. The king’s aim on arriving in Rochester was to destroy the bridge over the Medway, in order to cut off his enemies from their confederates in London. On the first attempt he failed; his men moved up the river in boats, setting fire to the bridge from underneath, but a force of sixty rebels beat them back and extinguished the flames. On their second attempt, however, the king’s men had the best of the struggle. The bridge was destroyed, and the rebels fell back to the castle.

This kind of reporting is invaluable, and some of the additional details that Ralph provides are no less compelling (he tells us, for instance, in the shocked tones that only an outraged monk can muster, how John’s men stabled their horses in Rochester Cathedral).

For the first time in English history, however, we do not have to rely entirely on writers like Ralph. From the start of John’s reign, we have another (and in some respects even better) source of information. When John came to the throne in 1199, the kings of England had long been in the habit of sending out dozens of written orders to their deputies on a daily basis. But John made an important innovation: he instructed his clerks to keep copies. Every letter the king composed was dutifully transcribed by his chancery staff on to large parchment rolls, and these rolls are still with us today, preserved in the National Archives. The beauty of this is that every letter is dated and located. Even if John’s orders were humdrum, we can still use them to track the king wherever and whenever he travelled. We know, for example, that on 11 October the king was at Ospringe, and that by 12 October he had reached Gillingham. His first order at Rochester was given on 13 October, and on the following day, he wrote to the men of Canterbury.

‘We order you,’ he said, ‘just as you love us, and as soon as you see this letter, to make by day and night all the pickaxes that you can. Every blacksmith in your city should stop all other work in order to make [them]… and you should send them to us at Rochester with all speed.’

From the outset, it seems, John was planning on breaking into Rochester Castle by force.

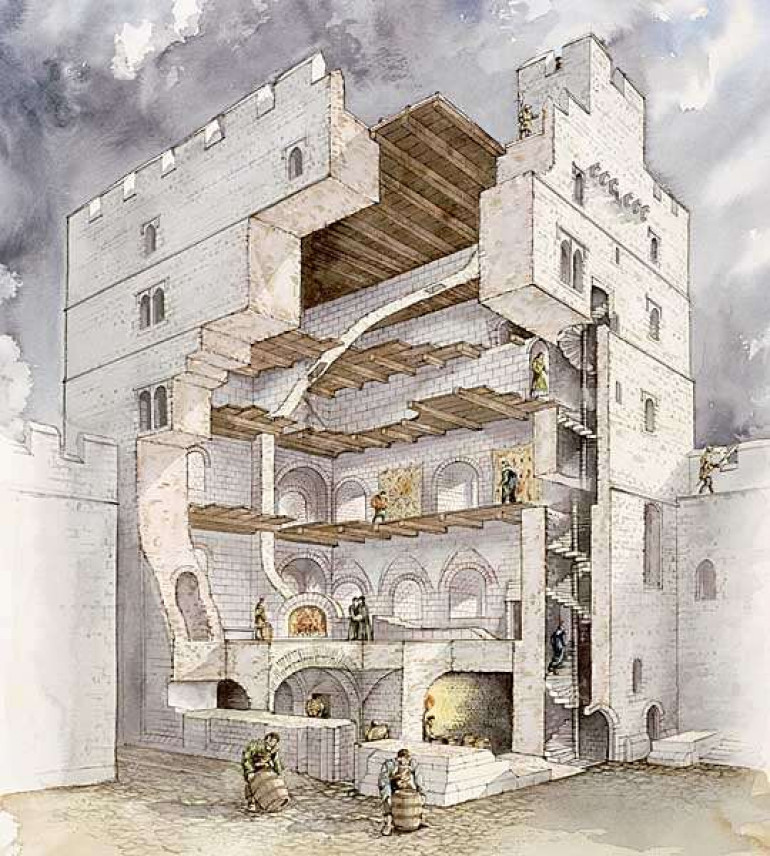

In the early thirteenth century, siege warfare was a fine art with a long history, and a wide range of options were available to an attacker. Certain avenues, however, were closed to John, because the tower at Rochester had been deliberately designed to foil them. The fact that the entrance was situated on the first floor, and protected by its forebuilding, ruled out the possibility of using a battering ram. Equally, the tower’s enormous height precluded any thoughts of scaling the walls with ladders, or the wheeled wooden towers known as belfries. Built of stone and roofed in lead, the building was going to be all but impervious to fire. Faced with such an obstacle, many commanders would have settled down and waited for the defenders to run out of food. John, however, had neither the time nor the temperament for such a leisurely approach, and embarked on the more dangerous option of trying to smash his way in. But simply getting close enough to land a blow on the castle was going to be enormously risky. We know for a fact that the men inside had crossbows.

Crossbows had been around since at least the middle of the eleventh century, and were probably introduced to England (along with cavalry and castles) at the time of the Norman Conquest. In some respects, they were less efficient killing machines than conventional longbows, in that their rate of ‘fire’ was considerably slower. To use a longbow (the simplest kind of bow imaginable), an archer had only to draw back the bowstring to his ear with one hand before releasing it; with a crossbow, the same procedure was more complicated. The weapon was primed by pointing it nose to the ground, placing a foot in the stirrup and drawing back the bow with both hands – a practice known as ‘spanning’. When the bowstring was fully drawn, it engaged with a nut which held it in position. The weapon was then loaded by dropping a bolt or ‘quarrel’ into the groove on top, and perhaps securing it in place with a dab of beeswax.

A Crusade

I have added three armed warrior knights to my Militis Christi of St Mary de Pratis Abbey, though they could be Templars from Rothey Temple. These are a very nice little set of figures and I have given them the same colours as the monks to match them in.

Robin Hood, Robin Hood, Riding through the Glen

One of the things I love about the Baron’s War range is the fact that in the reign of King John one of the best known outlaws, Robin Hood lived, in theory at least. Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is depicted as being of noble birth, and in modern retellings he is sometimes depicted as having fought in the Crusades before returning to England to find his lands taken by the Sheriff. In the oldest known versions he is instead a member of the yeoman class. Traditionally depicted dressed in Lincoln green, he is said to have robbed from the rich and given to the poor.

Through retellings, additions, and variations, a body of familiar characters associated with Robin Hood has been created. These include his lover, Maid Marian, his band of outlaws, the Merry Men, and his chief opponent, the Sheriff of Nottingham. The Sheriff is often depicted as assisting Prince John in usurping the rightful but absent King Richard, to whom Robin Hood remains loyal. His partisanship of the common people and his hostility to the Sheriff of Nottingham are early recorded features of the legend, but his interest in the rightfulness of the king is not, and neither is his setting in the reign of Richard I. He became a popular folk figure in the Late Middle Ages, and the earliest known ballads featuring him are from the 15th century (1400s).

There have been numerous variations and adaptations of the story over the subsequent years, and the story continues to be widely represented in literature, film, and television. Robin Hood is considered one of the best known tales of English folklore.

The historicity of Robin Hood is not proven and has been debated for centuries. There are numerous references to historical figures with similar names that have been proposed as possible evidence of his existence, some dating back to the late 13th century. At least eight plausible origins to the story have been mooted by historians and folklorists, including suggestions that “Robin Hood” was a stock alias used by or in reference to bandits.

Robin Hood

The historicity of Robin Hood has been debated for centuries. A difficulty with any such historical research is that Robert was a very common given name in medieval England, and ‘Robin’ (or Robyn) was its very common diminutive, especially in the 13th century; it is a French hypocorism, already mentioned in the Roman de Renart in the 12th century. The surname Hood (or Hude, Hode, etc.) was also fairly common because it referred either to a hooder, who was a maker of hoods, or alternatively to somebody who wore a hood as a head-covering. It is therefore unsurprising that medieval records mention a number of people called ‘Robert Hood’ or ‘Robin Hood’, some of whom are known to have fallen foul of the law.

Another view on the origin of the name is expressed in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica which remarks that ‘hood’ was a common dialectical form of ‘wood’; and that the outlaw’s name has been given as ‘Robin Wood’. There are a number of references to Robin Hood as Robin Wood, or Whood, or Whod, from the 16th and 17th centuries. The earliest recorded example, in connection with May games in Somerset, dates from 1518.

Early references

The oldest references to Robin Hood are not historical records, or even ballads recounting his exploits, but hints and allusions found in various works. From 1261 onward, the names “Robinhood”, “Robehod”, or “Robbehod” occur in the rolls of several English Justices as nicknames or descriptions of malefactors. The majority of these references date from the late 13th century. Between 1261 and 1300, there are at least eight references to “Rabunhod” in various regions across England, from Berkshire in the south to York in the north.

Leaving aside the reference to the “rhymes” of Robin Hood in Piers Plowman in the 1370s, and the scattered mentions of his “tales and songs” in various religious tracts dating to the early 1400s, the first mention of a quasi-historical Robin Hood is given in Andrew of Wyntoun’s Orygynale Chronicle, written in about 1420. The following lines occur with little contextualisation under the year 1283:

Lytil Jhon and Robyne Hude

Wayth-men ware commendyd gude

In Yngil-wode and Barnysdale

Thai oysyd all this tyme thare trawale.

In a petition presented to Parliament in 1439, the name is used to describe an itinerant felon. The petition cites one Piers Venables of Aston, Derbyshire, “who having no liflode, ne sufficeante of goodes, gadered and assembled unto him many misdoers, beynge of his clothynge, and, in manere of insurrection, wente into the wodes in that countrie, like as it hadde be Robyn Hude and his meyne.”

The next historical description of Robin Hood is a statement in the Scotichronicon, composed by John of Fordun between 1377 and 1384, and revised by Walter Bower in about 1440. Among Bower’s many interpolations is a passage that directly refers to Robin. It is inserted after Fordun’s account of the defeat of Simon de Montfort and the punishment of his adherents, and is entered under the year 1266 in Bower’s account. Robin is represented as a fighter for de Montfort’s cause. This was in fact true of the historical outlaw of Sherwood Forest Roger Godberd, whose points of similarity to the Robin Hood of the ballads have often been noted.

Then arose the famous murderer, Robert Hood, as well as Little John, together with their accomplices from among the disinherited, whom the foolish populace are so inordinately fond of celebrating both in tragedies and comedies, and about whom they are delighted to hear the jesters and minstrels sing above all other ballads.

The word translated here as ‘murderer’ is the Latin sicarius (literally ‘dagger-man’), from the Latin sica for ‘dagger’, and descends from its use to describe the Sicarii, assassins operating in Roman Judea. Bower goes on to relate an anecdote about Robin Hood in which he refuses to flee from his enemies while hearing Mass in the greenwood, and then gains a surprise victory over them, apparently as a reward for his piety; the mention of “tragedies” suggests that some form of the tale relating his death, as per A Gest of Robyn Hode, might have been in currency already.

Another reference, discovered by Julian Luxford in 2009, appears in the margin of the “Polychronicon” in the Eton College library. Written around the year 1460 by a monk in Latin, it says:

Around this time [i.e., reign of Edward I], according to popular opinion, a certain outlaw named Robin Hood, with his accomplices, infested Sherwood and other law-abiding areas of England with continuous robberies.

Following this, John Major mentions Robin Hood within his Historia Majoris Britanniæ (1521), casting him in a positive light by mentioning his and his followers’ aversion to bloodshed and ethos of only robbing the wealthy; Major also fixed his floruit not to the mid-13th century but the reigns of Richard I of England and his brother, King John. Richard Grafton, in his Chronicle at Large (1569) went further when discussing Major’s description of “Robert Hood”, identifying him for the first time as a member of the gentry, albeit possibly “being of a base stock and lineage, was for his manhood and chivalry advanced to the noble dignity of an Earl” and not the yeomanry, foreshadowing Anthony Munday’s casting of him as the disposed Earl of Huntingdon. The name nevertheless still had a reputation of sedition and treachery in 1605, when Guy Fawkes and his associates were branded “Robin Hoods” by Robert Cecil. In 1644, jurist Edward Coke described Robin Hood as a historical figure who had operated in the reign of King Richard I around Yorkshire; he interpreted the contemporary term “roberdsmen” (outlaws) as meaning followers of Robin Hood.

Robert Hod of York

The earliest known legal records mentioning a person called Robin Hood (Robert Hod) are from 1226, found in the York Assizes, when that person’s goods, worth 32 shillings and 6 pence, were confiscated and he became an outlaw. Robert Hod owed the money to St Peter’s in York. The following year, he was called “Hobbehod”, and also came to known as “Robert Hood”. Robert Hod of York is the only early Robin Hood known to have been an outlaw. L.V.D. Owen in 1936 floated the idea that Robin Hood might be identified with an outlawed Robert Hood, or Hod, or Hobbehod, all apparently the same man, referred to in nine successive Yorkshire Pipe Rolls between 1226 and 1234. There is no evidence however that this Robert Hood, although an outlaw, was also a bandit.

Robert and John Deyville

Historian Oscar de Ville discusses the career of John Deyville and his brother Robert, along with their kinsmen Jocelin and Adam, during the Second Barons’ War, specifically their activities after the Battle of Evesham. John Deyville was granted authority by the faction led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester over York Castle and the Northern Forests during the war in which they sought refuge after Evesham. John, along with his relatives, led the remaining rebel faction on the Isle of Ely following the Dictum of Kenilworth. De Ville connects their presence there with Bower’s mention of “Robert Hood” during the aftermath of Evesham in his annotations to the Scotichronicon.

While John was eventually pardoned and continued his career until 1290, his kinsmen are no longer mentioned by historical records after the events surrounding their resistance at Ely, and de Ville speculates that Robert remained an outlaw. Other points de Ville raises in support of John and his brothers’ exploits forming the inspiration for Robin Hood include their properties in Barnsdale, John’s settlement of a mortgage worth £400 paralleling Robin Hood’s charity of identical value to Sir Richard at the Lee, relationship with Sir Richard Foliot, a possible inspiration for the former figure, and ownership of a fortified home at Hood Hill, near Kilburn, North Yorkshire. The last of these is suggested to be the inspiration for Robin Hood’s second name as opposed to the more common theory of a head covering. Perhaps not coincidentally, a “Robertus Hod” is mentioned in records among the holdouts at Ely.

Although de Ville does not explicitly connect John and Robert Deyville to Robin Hood, he discusses these parallels in detail and suggests that they formed prototypes for this ideal of heroic outlawry during the tumultuous reign of Henry III’s grandson and Edward I’s son, Edward II of England.

Roger Godberd as Robin Hood

David Baldwin identifies Robin Hood with the historical outlaw Roger Godberd, who was a die-hard supporter of Simon de Montfort, which would place Robin Hood around the 1260s. There are certainly parallels between Godberd’s career and that of Robin Hood as he appears in the Gest. John Maddicott has called Godberd “that prototype Robin Hood”. Some problems with this theory are that there is no evidence that Godberd was ever known as Robin Hood and no sign in the early Robin Hood ballads of the specific concerns of de Montfort’s revolt.

Robin Hood of Wakefield

The antiquarian Joseph Hunter (1783–1861) believed that Robin Hood had inhabited the forests of Yorkshire during the early decades of the fourteenth century. Hunter pointed to two men whom, believing them to be the same person, he identified with the legendary outlaw:

- Robert Hood who is documented as having lived in the city of Wakefield at the start of the fourteenth century.

- “Robyn Hode” who is recorded as being employed by Edward II of England during 1323.

Hunter developed a fairly detailed theory implying that Robert Hood had been an adherent of the rebel Earl of Lancaster, who was defeated by Edward II at the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322. According to this theory, Robert Hood was thereafter pardoned and employed as a bodyguard by King Edward, and in consequence he appears in the 1323 court roll under the name of “Robyn Hode”. Hunter’s theory has long been recognised to have serious problems, one of the most serious being that recent research has shown that Hunter’s Robyn Hood had been employed by the king before he appeared in the 1323 court roll, thus casting doubt on this Robyn Hood’s supposed earlier career as outlaw and rebel.

Robin Hood as an alias

It has long been suggested, notably by John Maddicott, that “Robin Hood” was a stock alias used by thieves. What appears to be the first known example of “Robin Hood” as a stock name for an outlaw dates to 1262 in Berkshire, where the surname “Robehod” was applied to a man apparently because he had been outlawed. This could suggest two main possibilities: either that an early form of the Robin Hood legend was already well established in the mid-13th century; or alternatively that the name “Robin Hood” preceded the outlaw hero that we know; so that the “Robin Hood” of legend was so called because that was seen as an appropriate name for an outlaw.

Mythology

There is at present little or no scholarly support for the view that tales of Robin Hood have stemmed from mythology or folklore, from fairies or other mythological origins, any such associations being regarded as later development. It was once a popular view, however. The “mythological theory” dates back at least to 1584, when Reginald Scot identified Robin Hood with the Germanic goblin “Hudgin” or Hodekin and associated him with Robin Goodfellow. Maurice Keen provides a brief summary and useful critique of the evidence for the view Robin Hood had mythological origins. While the outlaw often shows great skill in archery, swordplay and disguise, his feats are no more exaggerated than those of characters in other ballads, such as Kinmont Willie, which were based on historical events.

Robin Hood has also been claimed for the pagan witch-cult supposed by Margaret Murray to have existed in medieval Europe, and his anti-clericalism and Marianism interpreted in this light. The existence of the witch cult as proposed by Murray is now generally discredited.

Associated locations

Sherwood Forest

The early ballads link Robin Hood to identifiable real places. In popular culture, Robin Hood and his band of “merry men” are portrayed as living in Sherwood Forest, in Nottinghamshire. Notably, the Lincoln Cathedral Manuscript, which is the first officially recorded Robin Hood song (dating from approximately 1420), makes an explicit reference to the outlaw that states that “Robyn hode in scherewode stod”. In a similar fashion, a monk of Witham Priory (1460) suggested that the archer had ‘infested shirwode’. His chronicle entry reads:

‘Around this time, according to popular opinion, a certain outlaw named Robin Hood, with his accomplices, infested Sherwood and other law-abiding areas of England with continuous robberies’.

Nottinghamshire

Specific sites in the county of Nottinghamshire that are directly linked to the Robin Hood legend include Robin Hood’s Well, located near Newstead Abbey (within the boundaries of Sherwood Forest), the Church of St. Mary in the village of Edwinstowe and most famously of all, the Major Oak also located at the village of Edwinstowe. The Major Oak, which resides in the heart of Sherwood Forest, is popularly believed to have been used by the Merry Men as a hide-out. Dendrologists have contradicted this claim by estimating the tree’s true age at around eight hundred years; it would have been relatively a sapling in Robin’s time, at best.

Yorkshire

Nottinghamshire’s claim to Robin Hood’s heritage is disputed, with Yorkists staking a claim to the outlaw. In demonstrating Yorkshire’s Robin Hood heritage, the historian J. C. Holt drew attention to the fact that although Sherwood Forest is mentioned in Robin Hood and the Monk, there is little information about the topography of the region, and thus suggested that Robin Hood was drawn to Nottinghamshire through his interactions with the city’s sheriff. Moreover, the linguist Lister Matheson has observed that the language of the Gest of Robyn Hode is written in a definite northern dialect, probably that of Yorkshire. In consequence, it seems probable that the Robin Hood legend actually originates from the county of Yorkshire. Robin Hood’s Yorkshire origins are generally accepted by professional historians.

Barnsdale

A tradition dating back at least to the end of the 16th century gives Robin Hood’s birthplace as Loxley, Sheffield, in South Yorkshire. The original Robin Hood ballads, which originate from the fifteenth century, set events in the medieval forest of Barnsdale. Barnsdale was a wooded area covering an expanse of no more than thirty square miles, ranging six miles from north to south, with the River Went at Wentbridge near Pontefract forming its northern boundary and the villages of Skelbrooke and Hampole forming the southernmost region. From east to west the forest extended about five miles, from Askern on the east to Badsworth in the west. At the northernmost edge of the forest of Barnsdale, in the heart of the Went Valley, resides the village of Wentbridge. Wentbridge is a village in the City of Wakefield district of West Yorkshire, England. It lies around 3 miles (5 km) southeast of its nearest township of size, Pontefract, close to the A1 road. During the medieval age Wentbridge was sometimes locally referred to by the name of Barnsdale because it was the predominant settlement in the forest. Wentbridge is mentioned in an early Robin Hood ballad, entitled, Robin Hood and the Potter, which reads, “Y mete hem bot at Went breg,’ syde Lyttyl John”. And, while Wentbridge is not directly named in A Gest of Robyn Hode, the poem does appear to make a cryptic reference to the locality by depicting a poor knight explaining to Robin Hood that he ‘went at a bridge’ where there was wrestling’. A commemorative Blue Plaque has been placed on the bridge that crosses the River Went by Wakefield City Council.

The Saylis

The Gest makes a specific reference to the Saylis at Wentbridge. Credit is due to the nineteenth-century antiquarian Joseph Hunter, who correctly identified the site of the Saylis. From this location it was once possible to look out over the Went Valley and observe the traffic that passed along the Great North Road. The Saylis is recorded as having contributed towards the aid that was granted to Edward III in 1346–47 for the knighting of the Black Prince. An acre of landholding is listed within a glebe terrier of 1688 relating to Kirk Smeaton, which later came to be called “Sailes Close”. Professor Dobson and Mr. Taylor indicate that such evidence of continuity makes it virtually certain that the Saylis that was so well known to Robin Hood is preserved today as “Sayles Plantation”. It is this location that provides a vital clue to Robin Hood’s Yorkshire heritage. One final locality in the forest of Barnsdale that is associated with Robin Hood is the village of Campsall.

Church of Saint Mary Magdalene at Campsall

The historian John Paul Davis wrote of Robin’s connection to the Church of Saint Mary Magdalene at Campsall in South Yorkshire. A Gest of Robyn Hode states that the outlaw built a chapel in Barnsdale that he dedicated to Mary Magdalene:

I made a chapel in Bernysdale,

That seemly is to se,

It is of Mary Magdaleyne,

And thereto wolde I be.

Davis indicates that there is only one church dedicated to Mary Magdalene within what one might reasonably consider to have been the medieval forest of Barnsdale, and that is the church at Campsall. The church was built in the late eleventh century by Robert de Lacy, the 2nd Baron of Pontefract. Local legend suggests that Robin Hood and Maid Marion were married at the church.

Grave at Kirklees

At Kirklees Priory in West Yorkshire stands an alleged grave with a spurious inscription, which relates to Robin Hood. The fifteenth-century ballads relate that before he died, Robin told Little John where to bury him. He shot an arrow from the Priory window, and where the arrow landed was to be the site of his grave. The Gest states that the Prioress was a relative of Robin’s. Robin was ill and staying at the Priory where the Prioress was supposedly caring for him. However, she betrayed him, his health worsened, and he eventually died there. The inscription on the grave reads,

Hear underneath dis laitl stean

Laz robert earl of Huntingtun

Ne’er arcir ver as hie sa geud

An pipl kauld im robin heud

Sick [such] utlawz as he an iz men

Vil england nivr si agen

Obiit 24 kal: Dekembris, 1247

Despite the unconventional spelling, the verse is in Modern English, not the Middle English of the 13th century. The date is also incorrectly formatted – using the Roman calendar, “24 kal Decembris” would be the twenty-third day before the beginning of December, that is, 8 November. The tomb probably dates from the late eighteenth century.

The grave with the inscription is within sight of the ruins of the Kirklees Priory, behind the Three Nuns pub in Mirfield, West Yorkshire. Though local folklore suggests that Robin is buried in the grounds of Kirklees Priory, this theory has now largely been abandoned by professional historians.

All Saints’ Church at Pontefract

Another theory is that Robin Hood died at Kirkby, Pontefract. Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion Song 28 (67–70), published in 1622, speaks of Robin Hood’s death and clearly states that the outlaw died at ‘Kirkby’. This is consistent with the view that Robin Hood operated in the Went Valley, located three miles to the southeast of the town of Pontefract. The location is approximately three miles from the site of Robin’s robberies at the now famous Saylis. In the Anglo-Saxon period, Kirkby was home to All Saints’ Church, Pontefract. All Saints’ Church had a priory hospital attached to it. The Tudor historian Richard Grafton stated that the prioress who murdered Robin Hood buried the outlaw beside the road,

Where he had used to rob and spoyle those that passed that way … and the cause why she buryed him there was, for that common strangers and travailers, knowing and seeing him there buryed, might more safely and without feare take their journeys that way, which they durst not do in the life of the sayd outlaes.

All Saints’ Church at Kirkby, modern Pontefract, which was located approximately three miles from the site of Robin Hood’s robberies at the Saylis, is consistent with Richard Grafton’s description because a road ran directly from Wentbridge to the hospital at Kirkby.

Place-name locations

Within close proximity of Wentbridge reside several notable landmarks relating to Robin Hood. One such place-name location occurred in a cartulary deed of 1422 from Monkbretton Priory, which makes direct reference to a landmark named Robin Hood’s Stone, which resided upon the eastern side of the Great North Road, a mile south of Barnsdale Bar. The historians Barry Dobson and John Taylor suggested that on the opposite side of the road once stood Robin Hood’s Well, which has since been relocated six miles north-west of Doncaster, on the south-bound side of the Great North Road. Over the next three centuries, the name popped-up all over the place, such as at Robin Hood’s Bay, near Whitby in Yorkshire, Robin Hood’s Butts in Cumbria, and Robin Hood’s Walk at Richmond, Surrey.

Robin Hood type place-names occurred particularly everywhere except Sherwood. The first place-name in Sherwood does not appear until the year 1700. The fact that the earliest Robin Hood type place-names originated in West Yorkshire is deemed to be historically significant because, generally, place-name evidence originates from the locality where legends begin. The overall picture from the surviving early ballads and other early references indicate that Robin Hood was based in the Barnsdale area of what is now South Yorkshire, which borders Nottinghamshire.

Maid Marian is the heroine of the Robin Hood legend in English folklore, often taken to be his lover. She is not mentioned in the early, medieval versions of the legend, but was the subject of at least two plays by 1600. Her history and circumstances are obscure, but she commanded high respect in Robin’s circle for her courage and independence as well as her beauty and loyalty.

History

Maid Marian (or Marion) is never mentioned in any of the earliest extant ballads of Robin Hood. She appears to have been a character in May Games festivities (held during May and early June, most commonly around Whitsun) and is sometimes associated with the Queen or Lady of May or May Day. Jim Lees in The Quest for Robin Hood (p. 81) suggests that Maid Marian was originally a personification of the Virgin Mary. Francis J. Childe argues that she originally was portrayed as a trull associated with a lascivious Friar Tuck: “She is a trul of trust, to serue a frier at his lust/a prycker a prauncer a terer of shetes/a wagger of ballockes when other men slepes.” Both a “Robin” and a “Marian” character were associated with May Day by the 15th century, but these figures were apparently part of separate traditions; the Marian of the May Games is likely derived from the French tradition of a shepherdess named Marion and her shepherd lover Robin, recorded in Adam de la Halle’s Le Jeu de Robin et Marion, circa 1283. It isn’t clear if there was an association of the early “outlaw” character of Robin Hood and the early “May Day” character Robin, but they did become identified, and associated with the “Marian” character, by the 16th century. Alexander Barclay, writing in c. 1500, refers to “some merry fytte of Maid Marian or else of Robin Hood”. Marian remained associated with May Day celebrations even after the association of Robin Hood with May Day had again faded. The early Robin Hood is also given a “shepherdess” love interest, in Robin Hood’s Birth, Breeding, Valor, and Marriage (Child Ballad 149), his sweetheart is “Clorinda the Queen of the Shepherdesses”. Clorinda survives in some later stories as an alias of Marian.

The “gentrified” Robin Hood character, portrayed as a historical outlawed nobleman, emerges in the late 16th century. From this time, Maid Marian is cast in terms of a noblewoman, but her role was never entirely virginal, and she retained aspects of her “shepherdess” or “May Day” characteristics; in 1592, Thomas Nashe described the Marian of the later May Games as being played by a male actor named Martin, and there are hints in the play of Robin Hood and the Friar that the female character in these plays had become a lewd parody. Robin originally was called Ryder.

In the play, The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntingdon by Anthony Munday, which was written in 1598, Marian appears as Robin’s lawfully-wedded wife, who changes her name from Matilda when she joins him in the greenwood. She also has a cousin called Elizabeth de Staynton who is described as being the Prioress of Kirklees Priory near Brighouse in West Yorkshire. The 19th century antiquarian, Joseph Hunter, identified a Robert Hood, yeoman from Wakefield, Yorkshire, in the archives preserved in the Exchequer, whose personal story matched very closely the story of Robin in Anthony Munday’s play, and this Robert Hood also married a woman named Matilda, who changed her name to Marian when she joined him in exile in Barnsdale Forest (following the Battle of Boroughbridge) in 1322, and who also had a cousin named Elizabeth de Staynton who was Prioress of Kirklees Priory. If these parallels are not coincidental, then the Marian of Robin Hood fame, whose origins may be distinct from the Marian of the May games or of Monday’s play, may derive all her roots from her association with the historical Robert Hood of Wakefield.

In an Elizabethan play, Anthony Munday identified Maid Marian with the historical Matilda, daughter of Robert Fitzwalter, who had to flee England because of an attempt to assassinate King John (legendarily attributed to King John’s attempts to seduce Matilda). The “Matilda” theory of Maid Marian is further discussed in In later versions of Robin Hood, Maid Marian is commonly named as “Marian Fitzwalter”, only child of the Earl of Huntingdon, is the Maid Marian in McSpadden, J. Walker (1926). “Chapter I: How Robin Hood Became An Outlaw”. Robin Hood. London, UK: George Harrap – via Project Gutenberg.

In Robin Hood and Maid Marian (Child Ballad 150, perhaps dating to the 17th century), Maid Marian is “a bonny fine maid of a noble degree” said to excel both Helen and Jane Shore in beauty. Separated from her lover, she dresses as a page “and ranged the wood to find Robin Hood,” who was himself disguised, so that the two begin to fight when they meet. As is often the case in these ballads, Robin Hood loses the fight to comical effect, and Marian only recognizes him when he asks for quarter. This ballad is in the “Earl of Huntington” tradition, a supposed “historical identity” of Robin Hood forwarded in the late 16th century.

20th-century pop culture adaptations of the Robin Hood legend almost invariably have featured a Maid Marian and mostly have made her a highborn woman with a rebellious or tomboy character. In 1938’s The Adventures of Robin Hood, she is a courageous and loyal woman (played by Olivia de Havilland), and a ward of the court, an orphaned noblewoman under the protection of King Richard. Although always ladylike, her initial antagonism to Robin springs not from aristocratic disdain but from aversion to robbery.

In The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men (1952), she, despite being a lady-in-waiting to Eleanor of Aquitaine during the Crusades, is in reality a mischievous tomboy capable of fleeing boldly to the countryside disguised as a boy. In the Kevin Costner epic Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, she is a maternal cousin to the sovereign, while in the BBC adaption of 2006, she is the daughter of the former sheriff and was betrothed to Robin before his leaving for the Holy Land, and in his absence embarked on her own crusade against poverty in aiding the poor in a fashion similar to what Robin later achieved, becoming a skilled fighter in the process and leading the people to refer to her as ‘The Night Watchman’.

Maid Marian’s role as a prototypical strong female character has made her a popular focus in feminist fiction. Theresa Tomlinson’s Forestwife novels (1993–2000) are told from Marian’s point of view, portray Marian as a high-born Norman girl escaping entrapment in an arranged marriage. With the aid of her nurse, she runs away to Sherwood Forest, where she becomes acquainted with Robin Hood and his men.

Little John is a companion of Robin Hood who serves as his chief lieutenant and second-in-command of the Merry Men. He is one of only a handful of consistently named characters that relate to Robin Hood and one of the two oldest Merry Men, alongside Much the Miller’s Son. His name is an ironic reference to his giant frame, as he is usually portrayed in legend as a huge warrior – a seven-foot-tall master of the quarterstaff.

Folklore

Little John appears in the earliest recorded Robin Hood ballads and stories and in the earliest references to Robin Hood by Andrew of Wyntoun in 1420 and by Walter Bower in 1440. In the early tales, Little John is shown to be intelligent and highly capable. In “A Gest of Robyn Hode”, he captures the sorrowful knight and, when Robin Hood decides to pay the knight’s mortgage for him, accompanies him as a servant. In “Robin Hood’s Death”, he is the only one of the Merry Men that Robin takes with him. In the 15th-century ballad commonly called “Robin Hood and the Monk”, Little John leaves in anger after a dispute with Robin. When Robin Hood is captured, it is Little John who plans his leader’s rescue. In thanks, Robin offers Little John leadership of the band, but John refuses. Later depictions of Little John portray him as less cunning.

The earliest ballads do not feature an origin story for this character. According to a 17th-century ballad, he was a giant of a man who was at least seven feet tall, and introduced when he tried to prevent Robin from crossing a narrow bridge, whereupon they fought with quarterstaves, and Robin was overcome. Despite having won the duel, John agreed to join his band and fight alongside him. From then on he was called Little John in whimsical reference to his size. This scene is almost always re-enacted in film and television versions of the story. In some modern film versions, Little John loses the duel to Robin.

Starting from the ballad tradition, Little John is commonly shown to be the only Merry Man present at Robin Hood’s death.

Despite a lack of historical evidence for his existence, Little John is reputed to be buried in a churchyard in the village of Hathersage, Derbyshire. A modern tombstone marks the supposed location of his grave, which lies under an old yew tree. This grave was owned by the Nailor (Naylor) family, and sometimes some variation of “Nailer” is given as John’s surname. In other versions of the legends, his name is given as John Little, enhancing the irony of his nickname.

According to local legend, Little John built himself a small cottage across the River Derwent from the family home. The site now has a 15th century Grade 2 listed ex-farmhouse and barn built on it, called Nether House at Offerton.

In Dublin, a local legend suggests that Little John visited the city in the 12th century and was hanged there.

Little John was a figure in the Robin Hood plays and games during the 15th to 17th centuries, particularly those held in Scotland.

Many historical figures are named Little John and John Little, but it is debatable which – if any – are the inspiration for the legendary character.

Friar Tuck is a companion to Robin Hood in the legends about that character.

History

Tuck is a common character in modern Robin Hood stories, which depict him as a jovial friar and one of Robin’s Merry Men. The figure of Tuck was common in the May Games festivals of England and Scotland during the 15th through 17th centuries. He appears as a character in the fragment of a Robin Hood play from 1475, sometimes called Robin Hood and the Knight or Robin Hood and the Sheriff, and a play for the May games published in 1560 which tells a story similar to “Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar”. (The oldest surviving copy of this ballad is from the 17th century.) The character entered the tradition through these folk plays, and he was originally partnered with Maid Marian: “She is a trul of trust, to serue a frier at his lust/a prycker a prauncer a terer of shetes/a wagger of ballockes when other men slepes”. His appearance in “Robin Hood and the Sheriff” means that he was already part of the legend around the time when the earliest surviving copies of the Robin Hood ballads were being made.

A friar with Robin’s band in the historical period of Richard the Lion-Hearted would have been impossible because the period predates friars in England (but see Eustace the Monk, a medieval outlaw); however, the association of Robin Hood with Richard I was not made until the 16th century; the early ballad “A Gest of Robin Hood” names his king as “Edward”.

What follows is a story which includes different versions of the legend. He was a former monk of Fountains Abbey (or in some cases, St Mary’s Abbey in York, which is also the scene of some other Robin Hood tales) who was expelled by his order because of his lack of respect for authority. Because of this, and in spite of his taste for good food and wine, he became the chaplain of Robin’s band. In Howard Pyle’s The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, he was specifically sought out as part of the tale of Alan-a-Dale: Robin has need of a priest who will marry Allan to his sweetheart in defiance of the Bishop of Hereford.

In many tales, from “Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar” to The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, his first encounter with Robin results in a battle of wits in which first one and then the other gains the upper hand and forces the other to carry him across a river. This ends in the Friar tossing Robin into the river.

In some tales, he is depicted as a physically fit man and a skilled swordsman and archer with a hot-headed temper. However, most commonly, Tuck is depicted as a fat, bald and jovial monk with a great love of food and ale, though the two are not mutually exclusive. Sometimes, the latter depiction of Tuck is the comic relief of the tale.

Two royal writs in 1417 refer to Robert Stafford, a Sussex chaplain who had assumed the alias of Frere Tuk. This “Friar Tuck” was still at large in 1429. These are the earliest surviving references to a character by that name.

Will Scarlet (also Scarlett, Scarlock, Scadlock, Scatheloke, Scathelocke and Shacklock) is a prominent member of Robin Hood’s Merry Men. He is present in the earliest ballads along with Little John and Much the Miller’s Son.

The confusion of surnames has led some authors to distinguish them as belonging to different characters. The Elizabethan playwright Anthony Munday featured Scarlet and Scathlocke as half-brothers in his play The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntington. Howard Pyle included both a Will Scathelock and a Will Scarlet in his Merry Adventures of Robin Hood. Will Stutely may also exist as a separate character because of a mistaken surname.

Charge and Cry Havoc!

I have been playing about this evening with my The Barons’ War by Warhost and Footsore figures sculpted by the wonderfully talents Paul Hicks. The character in these figures is amazing and so full of life. Great stuff. I so love this range of figures and the history around the First Barons’ War and Robin Hood too.

Stanley Hotoft of Humerstan and William de Huntingfield

Here is Stanley Hotoft of Humerstan, in the white ermine, and William de Huntingfield, in the yellow and I am chuffed with the way they have turned out. I am truly loving this period, doing the research and paint the heraldry and enjoying it.

Stanley Hotoft of Humerstan is not really based on a real person and the heraldry is not based on a real heraldry, he is actually based on my wife’s childhood toy, I flat knitted mule called Flat Muffin. I have based the heraldry on the mule, horse actually and the colours because Flat Muffin is white.

William of Huntingfield was a medieval English baron, Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk and one of the Magna Carta sureties. He held Dover Castle for King John from September 1203 (as a Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports) and in exchange, the king took his son and daughter hostage. He was granted the lands seized from his disgraced brother and appointed Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk for 1210 and 1211. In the First Barons’ War he was an active rebel against King John and one of the twenty-five chosen to oversee the observance of the resulting Magna Carta. He subsequently supported the French invasion of England, and took part in the Fifth Crusade, where he died.

This now bring me to 75 painted, 11 mounted but it still means that I have another 60 to paint including 16 mounted. Also I think I am going to get the Fortified Manor, The Dark Age Fort Bundle from Sarissa Precision for the game too, if it looks right, which I think it does.

Medieval Colours

I am no expect on Medieval colours in anyway, I basically find a colour I like the look of and go with that. Basically if it looks right it is.

However, I have discovered this wonderful website to help me too and I was surprised by just how bright they can be.

I think it will be of use for other periods and genres too.

Sir William Rimet and Sir Gilles Dubois

May I introduce two more mounted Lords , Sir William Rimet and Sir Gilles Dubois. These are the commanders of the next two 500 point forces I am building and also can be used as simple normal knights too. The actually miniatures are characters from Footsores Barons’ War range, them being the evil King John and Falkes de Breaute.

Sir William Rimet (King John) is painting using the England football team badge for the heraldry and team colours for the tunic and team. I have hand painted the shield and the horse curtains and I think the over look is right. Interest fact is about the England team badge is that it was actually based on the Plantagenet shield, so this is fitting.

Sir Gilles Dubois (Falkes de Breaute) is not based off any thing other than I like the colours and any resemblance to a East Anglian football team is accidental, them being Norwich City. I wanted a Dragon or Drake rampant on the shield and though I am not to sure if historically they had dragons on the shield, it looks cool and again this is hand painted on there.

Jérémie Colman of Bawburgh

Jérémie Colman of Bawburgh is one of the Lords in this group, he is the one in Green and Yellow quartered tunic. He is actually based of the colours of a football team, in this case it is Norwich City, and actually the name of the knight, Jérémie Colman of Bawburgh, is a local Norwich hero, Colman’s Mustard. I thought it would be a wee bit of fun to add in him and also shows that you can take anything to make them sound like a knight.

Roger la Zouche

I have based these well one of the on Roger la Zouche, a local Lord, he is the one in yellow tunic with a red helmet.

Roger la Zouche is

A Witness to Henry III’s Confirmation of The Magna Carta.

Second Lord Zouche.

Heir To Brother William 1199.

Sheriff of Devonshire 1228-31.

Second Lord Zouche. Sheriff of Devonshire 1228-31.. A witness to Henry III’s confirmation of the Magna Carta. Heir to brother William 1199.

A Fight in Leicestershire

Jérémie Colman of Bawburgh clashes with Roger la Zouche in The Barons’ War: by Warhost and Footsore.

Some More Scenery, A Blacksmith's Forge

I have added a terrain piece or maybe even an objective for the Barons’ War game and I think it fits in nicely. The forge comes from Iron Gate Scenery and has an LED that fires up the forge, it comes with the kit, I am not Blinky, not got the skills. It is a lovely kit and I had fun painting this and I think it fits the period as well as a number of other games too.

Eustace de Vesci

Eustace de Vesci (1169/70-1216) was one of the group referred to by contemporaries as ‘the Northerners’, the original hard-line leaders of the baronial resistance to King John. The son of William de Vesci and Burga, daughter of Robert de Stuteville, lord of Cottingham (Yorks.), he was lord of Alnwick in Northumberland and an extensive landowner in northern England. He was married to Margaret, illegitimate daughter of William the Lion, king of Scotland and half-sister of Alexander II of Scotland. At Richard the Lionheart’s second coronation in 1194, following his release from captivity in Germany, he witnessed a royal charter in favour of his father-in-law.

At the end of 1194 Eustace is found engaged in Richard’s service at Chinon, the great Angevin castle in Anjou, and five years later was one of the guarantors of the treaty between King John, newly succeeded to the throne, and Count Renaud of Boulogne. In 1210 he accompanied John on his expedition to attempt the pacification of Ireland. Accused in 1212, alongside another important northern lord Robert FitzWalter, of plotting against John’s life, he fled to Scotland, and his lands were seized. After John’s submission to the pope in 1213, however, he was allowed back, and a few months later he was awarded restitution of his lands, although his castles at Alnwick and Malton were destroyed.

Later in 1213 in a gesture indicative of his continued defiance of the king, he refused to enlist in John’s expedition to Poitou, in south-west France, and in the following year he also refused to pay scutage (money in lieu of military service). His intense dislike of John was evidently well known to the pope who, in 1214, warned him to remain loyal to the king, since his submission to the pope regarded as a faithful son of the Church. In 1215 he was deeply involved in the military operations that led up to the making of Magna Carta, associating himself closely with a Yorkshire rebel, his kinsman Robert de Ros of Helmsley. In September he was one of a group of nine malcontent barons singled out for excommunication by the pope.

Although by the following May he was seeking a reconciliation with the king, as soon as Louis, the French king’s son, took on the leadership of the baronial cause he went over to him. He met his death in late August 1216 at Barnard Castle in County Durham, where he was shot in the head by an arrow while conducting siege operations. He left a young son William, who came of age in 1226.

Robert de Vere

Robert de Vere (d. 1221) was a member of a comital family, based at Hedingham (Essex), which owed its rise to rise to eminence to the patronage of the Empress Matilda in the civil war of King Stephen’s reign in the 1140s. Robert himself was the third surviving son of Earl Aubrey (d. 1194) by his third wife, Agnes of Essex, and succeeded to the title on the death of his elder brother, another Aubrey in October 1214. Sometime before Michaelmas 1207 Robert had married Isabel de Bolebec, the aunt and namesake of Earl Aubrey’s wife, who had died childless in 1206 or 1207. Isabel the niece had been the heiress to the Bolebec estate, which was centred on Whitchurch (Bucks.), and her own heirs were her two aunts. Robert’s marriage can therefore be seen as part of a de Vere strategy to retain control over at least half of the Bolebec lands. The de Veres were one of the least well-endowed of the comital families and would have been loath to allow a valuable estate to slip from their grasp.

Robert’s defection to the rebel side in 1215 provides yet another example of King John’s capacity to alienate men who should have been numbered among his natural allies. His predecessor in the title had been one of the king’s most loyal intimates and administrators. Robert was probably moved to defect in part by his resentment at the relief of 1000 marks charged for his entry into his inheritance, which was high for an estate of only moderate extent. Most of all, however, he probably nursed a grievance against the king for his failure to confirm him in the title of earl and in the office of court chamberlain, which de Veres held by hereditary right. Robert is known to have been present at the baronial muster at Stamford in April 1215 and he was named by the chronicler Roger Wendover as one of the principal promoters of discontent. He was a key figure in the East Anglian group of rebels. By 23 June, after the meeting at Runnymede, the king was evidently angling to regain his support because on that date a royal letter was issued which implicitly recognised him as earl of Oxford. By that time, however, it was too late: Robert had already been named to the Twenty Five. Towards the end of March 1216 John took possession of his castle at Hedingham after a three-day siege and the earl, who was not present, was granted a safe-conduct to seek the king’s forgiveness. Within months, however, he had defected to Louis of France and he was not to re-enter royal allegiance for good until the general settlement of the rebellion in the autumn of 1217.

Robert died shortly before 25 October 1221 and was buried in Hatfield Broad Oak priory (Essex). A century after his death, to mark the long-delayed completion of the priory church, a fine tomb effigy to his memory was commissioned, carved by the same sculptors who produced the monument to Aymer de Valence, earl of Pembroke, in Westminster Abbey. At the Dissolution, the effigy was transferred to Hatfield Broad Oak parish church, where it remains. Robert’s widow obtained the guardianship of their son, Hugh, who was a minor, and of his estates, which she was to exercise for about ten years. She died on 3 February 1245 and was buried in the Dominican friary at Oxford, nearer to her own family’s estates.

Geoffrey de Say

Geoffrey de Say sat in the baronial camp in an uneasy alliance with Geoffrey de Mandeville, his cousin but also his rival for the inheritance of the de Mandeville earls of Essex. The competition between the two men and their families affords a reminder that there were divisions within the baronial camp as well as between the rebel barons and the king. No more than such other medieval opposition movements as the Ordainers in Edward II’s reign or the Appellants in Richard II’s were the Twenty Five of John’s reign a solid monolithic bloc unhindered by faction or rivalry.

The two Geoffreys both had a claim on the estates of another namesake, William de Mandeville, third earl of Essex, the last of his line, who had died without issue in 1189. De Say’s claim arose from his grandmother, the long-lived Beatrice de Say, the first Mandeville earl’s sister, who transmitted her rights to her son, while Geoffrey de Mandeville’s claim was inherited from his mother, another Beatrice, the wife of Geoffrey FitzPeter and daughter and eventual coheiress of William de Say II, William I’s son. Geoffrey de Say I, our Geoffrey’s father, obtained a grant of the disputed lands from Richard the Lionheart in 1189, but was unable to raise the huge sum of 7,000 marks (about £2333), which the king demanded as his price. The estates, accordingly, reverted to the king and were awarded instead to Geoffrey FitzPeter, a powerful man and later King Richard’s justiciar. FitzPeter and his wife were confirmed in their possession of the estates by a royal charter granted at Messina on 23 January 1191. The early stages of the dispute are told in a fascinating account in the Walden Abbey chronicle, The Foundation Book of Walden Monastery.

The younger Geoffrey had started his career under Richard and John fighting in the defence of Normandy and had evidently lost property there when the duchy was finally overrun by the French. As early as 1202 the duchy’s seneschal was instructed to find as much as one hundred liberates of land with which to compensate him for the losses which he had suffered.

In 1214, after his father’s death, he reactivated the family claim to the Mandeville inheritance, this time against FitzPeter’s son – Earl Geoffrey – taking advantage of his service with the king in Poitou to offer him no less than 15,000 (£10,000) marks for possession. John wrote to the justiciar in England ordering him to take advice on what might be the best course to take. No further action is recorded, and presumably the justiciar did nothing. It is no surprise, therefore, in 1215 to find Geoffrey on the rebel side, aggrieved at his failure to secure justice. In June he was named to the Twenty Five and in November he was involved alongside FitzWalter and de Clare in the fruitless negotiations with the king for a settlement. Siding with Louis and the French, he only made his peace with the royalists after the massive baronial defeat at Lincoln in May. He was not active in the politics of the Minority. In 1219 he went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and in 1223 to Santiago de Compostella, apparently in the company of Earl Warenne. He died on 24 August 1230 while campaigning with Henry III in Poitou.

Geoffrey married Alice de Chesney, whose date of death is unknown, and he left a son William, who succeeded him and lived to 1271.

The Completed Force, So Far

Here is all of the first wave of the Barons’ War range fully painted up and jolly please I am with the look of it. I think I have captured the look and feel of a medieval army from the early 13th century.