Returning to Gangs of Rome

Recommendations: 27

About the Project

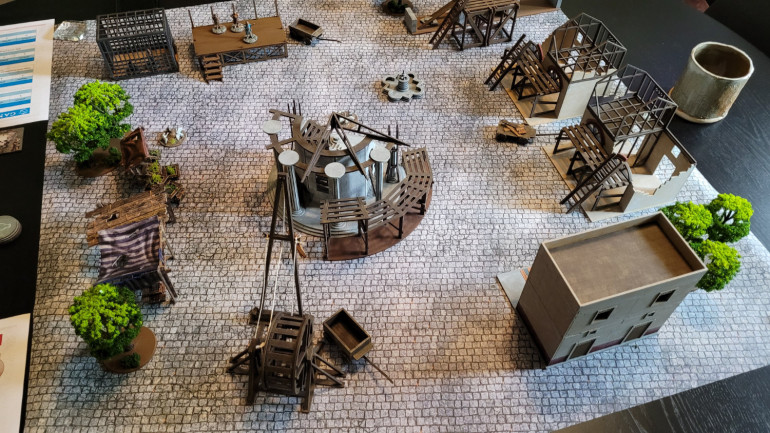

Time to try out the newly revised Gangs of War rules. I'll play through the three basic scenarios using the sample gangs provided in the rules. I'll also most likely try out some (if not all) of the advanced rules such as the Vigiles (Roman policemen), unsafe terrain, throwing scatter terrain, and the incola, the individual non-player denizens of the city.

Related Game: Gangs Of Rome

Related Company: Footsore Miniatures and Games

Related Genre: Historical

This Project is Active

Scenario II: Market Opportunity

We’re back after an appalling five months since our last game of Gangs of Rome. Join us as we struggle to remember how to play…

This scenario is more or less the same as the first, except that the three objective markers all start in the center of the board. The goal is still to be in possession of at least two objective tokens at the end of five rounds. Since there aren’t any new rules to learn, we took this opportunity to add two more non-player character types to the mix: the Vigiles, who function as a sort of police force, and a few Incola, individual characters who have a unique effect when a gang fighter gets near them.

We definitely went a little overboard here, with five mobs plus three Incola plus the Vigiles. The game’s token sheet only comes with six of the red mob tokens — you’re supposed to add a token for each mob, plus one for each Incola, which left us two tokens short. We were able to substitute easily enough, but in retrospect, a limit of six total mobs plus Incola seems like a good guideline to follow. The large number of NPCs made for a fairly crowded table, plus a lot of rules overhead to keep track of.

In addition to learning some new rules, we decided to take the training wheels off and put together our own gang fighter lists rather than use the starter lists from the rule book. We each took one of the Rome’s Most Wanted three-fighter gangs detailed in the book, and then filled out our lists with individual fighters. The first edition of GoR came with randomly generated stat cards for each model you bought, but that proved cumbersome (and a little expensive, I imagine) so the second edition rule book includes random tables, allowing players to accomplish much the same thing, but with a degree of wiggle room if they’re trying to generate stats for a specific figure. I converted some of my first edition cards, and randomly generated stats for some of the newer models, so we were both able to put together something close to the 200 points recommended for a regular game.

My opponent opted to use the Daughters of Sappho as her base gang, adding a selection of additional female fighters (all, coincidentally, leftovers from the first edition). I chose to counter with the Oscan Players, a new gang whose models were part of the second edition Kickstarter campaign, along with one each of the newly introduced specialist fighters: rixa (brawler), agilitas (acrobat), and furtum (thief). I’m thinking the thief in particular will be useful, with his ability to steal objectives from opposing gang fighters.

For Incola we chose the Puppeteer, the Centurion of the Vigiles, and good old Rufinus, the Scorpion Thrower. Our possibly overcrowded table made placing the mobs according to the rules (8″ away from table edges and other mobs) difficult to the point of impossible, but we did the best we could and got the game started.

The game uses a random token draw to determine turn order, with additional tokens added to the bag for the NPCs, allowing the player who draws one to move a mob or Incola in a way that will hopefully be beneficial to them. The mobs react if attacks are made to close to them, and most of the Incola effects depend on proximity as well, so it’s sometimes possible to turn them to your advantage, or at least get them out of your way.

In round one I managed to rush to the center and grab two of the objectives, while my opponent ran afoul of the Scorpion Thrower — Rufinus throws scorpions at any mob or gang fighter that moves within 6″ of him. Unfortunately he didn’t last long, as he got too close to an angry mob who didn’t appreciate having scorpions thrown at them and got trampled to death.

The Puppeteer managed to get a few early jabs in. Any gang fighter within 4″ of him gets insulted by his puppet, reducing their attack or defense stats for their next activation. When my opponent got an opportunity to move him, the Puppeteer ran and hid behind some market stalls, where he remained for much of the game.

In round two, my acrobat who managed to snatch one of the objectives retreated to a construction scaffolding where we got to explore one more rules addition: the ability to throw items such as roof shingles or clay pots at opposing gang fighters. My opponent had one of her fighters pursue to a nearby scaffolding, where we proceeded to throw roof tiles at each other. The rules for this are very straightforward, with proximity to a piece of scatter terrain conferring the ability to make a ranged attack. Since the game allows for counterattacks and we were both standing next to piles of roof tiles, we ended up with quite the flurry of construction material.

I tried really hard to get my thief into position to steal one of my opponent’s objectives. He got into base contact, but failed on the steal action, allowing my opponent’s gang fighter to wallop him. Meanwhile, my opponent smacked down my other objective carrier and was able to grab a second objective, then retreated most of her models to her side of the board. I gave chase, and in round three my thief finally managed to earn his pay and grab another objective. Meanwhile my acrobat, still holding an objective, retreated to my end of the board to pick slivers of roof tile out of his hair.

We misread and/or forgot some of the rules governing the Vigiles, so they didn’t make an appearance until round three. The Vigiles are two models on a single 40mm base, who begin play off the board. At the start of the game a disturbance counter is set for a d6 plus the number of rounds in the game (in this case five) — we started with the disturbance counter at 8. Every time any mob reacts to a gang fighter attack, or is forced to react by a player moving them, the disturbance counts down 1. When it gets to zero, the Vigiles appear, adjacent to the mob that triggered them, and them move to attack the nearest gang fighter.

Of all the NPCs, the Vigiles have the most rules overhead. You need to remember to count down their timer, but also, once they are in play they react to every gang fighter aactivity any time a mob reacts within their line of sight. Their larger bases can sometimes make it difficult for them to get to their targets, which is thematic of guards fighting their way through a crowd but also required a fair amount of consensus when determining their targets.

By round four we had quite the scrum going, with my brawler fighting it out with Urganalla, one of my opponent’s Daughters of Sappho. They were backed into a corner and surrounded by an angry mob and two sets of Vigiles all baying for their blood. Plus a dog (the Fierce Mastiff from GoR first edition who I recreated as a regular gang fighter). There was a lot of back and forth but in the end my opponent held on to the objective.

With all the re-learning we had to do, we ran out of time and decided to call the game at the end of round four. Honestly we couldn’t really see how anything that might happen in a fifth round would change things, as Urganalla had my brawler on the ropes, and each of us had managed to move one of the other two objectives out of reach. The game was great fun though, although as mentioned earlier we definitely tried to pile too much optional stuff on for what was only our second-ever game. Lessons learned for next time: stick to six or fewer NPCs (incola, mobs and Vigiles combined), start the game a little earlier in the day, and try not to wait five months wait five months between games…

We’ll be back for Scenario III: Bounty, hopefully sooner rather than later.

Scenario I: Looting

This scenario seems designed to cover the basics of chasing down objectives. The goal is to be holding the most objective tokens at the end of five rounds, so not only do you have to collect them, but you have to hold on to them for the duration of the game. It’s a little more interesting than a last man standing type of game, as the characters who pick up objectives then become priority targets.

The setup also serves as an introduction to the “token draw” style of determining turn order. Colored tokens are added to a bag (or in our case, a Roman-looking cup), along with a third color (red) that represents the three non-player mobs. We start out by placing two tokens for each player in the cup, then drawing them to determine who gets to place the objectives. Interestingly, there isn’t anything to prevent us from placing objectives in our starting areas.

I like the token draw system for this kind of game, I think it reflects the idea that this is a chaotic street brawl, not an orderly military action. When a player draws a red token they get to either move a mob (rolling a die for the distance moved) or force a reaction, which is determined by a die roll and can either be scared (they run away), neutral, or angry (they attack the nearest player figure).

After objectives are placed, we refill the cup with tokens, drawing them to determine the starting placement for our gang fighters and the three mobs. Once that’s done, we’re ready to start.

In the first round we both focused on getting as close as possible to the objectives. We each placed one objective in our respective starting areas. so we were able to easily collect one objective each, although my opponent tried to make it diffucult for me by putting one of the mobs in my path. With one objective claimed by each of us, our remaining gang fighters moved towards the remaining objectives, one of which was up on some scaffolding.

As round two started, we both decided to try to protect our fighters who were holding objectives. My opponent’s solution was to blend with the mob, an action that allows a fighter to effectively hide in the crowd. When in base contact with a mob, the fighter can use the blend action to temporarily leave the board. At the start of their next activation, that fighter is placed in base contact with any of the three mobs on the board (it doesn’t have to be the one they originally blended with). It’s a great feature of the game that really gets across the idea that the streets are crowded with people and it’s easy to lose yourself in the throng.

I decided to have my fighter climb to the top of the under construction temple in the center of the board, reasoning that at least I would have limited avenues of approach to defend. What I didn’t think about was the fact that this figure was far and away my most effective fighter, so having him hide out for the whole game was a bit of a waste.

Meanwhile, we both rushed the two remaining objectives with our other fighters. The action economy in Gangs of Rome is really interesting, and quite different from the usual “each model can do two actions” that we see in most games. In Gangs of Rome, when a fighter activates they can choose to do between one and four actions. The player has to declare what the actions will be, using tokens to mark them on the board. For example, a player might declare “Marcus will move to this spot, then climb the scaffolding, then move into base contact with Rufus, then make a melee attack against Rufus.” That player then rolls dice equal to the fighter’s agility value (generally between 5 and 7); any result of 4 or better is a success, and the number of successes determines how many of the actions can be resolved. If any planned actions go unresolved, the fighter accumulates stress, which reduces his agility value until it is cleared.

One of the unclaimed objectives was up on some scaffolding, which limited how many fighters could get to it and fight over it. My opponent reached it first but wasn’t able to pick it up. I attempted a dramatic action with Manlius, one of my fighters. The plan was to climb up onto a closer bit of scaffolding, run across it, leap the gap to the scaffolding with the objective, and then pick it up. Planning four actions was a bit risky since Manlius only had an agility of 5, meaning I would need to roll 4 or better on four of the five dice. Unfortunately I only managed three, so Manlius made it to the objective but wasn’t able to pick it up, and he gained a stress for his trouble.

On the other side of the board, we ran into our first taste of combat, which is gloriously simple. The attacker rolls a number of dice equal to their attack value, with any 4, 5, or 6 being a hit. This is especially easy with the themed Roman numeral dice — you’re just looking for any result with a V in it. The defender then rolls dice equal to their defense value, with any 4, 5 or 6 blocking one of the hits. The defender takes damage equal to the number of unblocked hits. Combat is made a little more exciting when the defender only takes 1 or no damage; then they get to do a counterattack, following the same roll attack/roll defense steps. It’s all very simple and straightforward, which makes for a nice change after some of the more convoluted rules sets out there.

The marketplace brawl continued into the next round, eventually resulting in my side’s first casualty and my opponent claiming a second objective. Eventually I was able to get Marcus, my gang’s MVP, over to that area of the board to take down my opponent’s fighter and snatch the objective, giving me two of the four but with the same figher holding both of them, making him a prime target.

The scuffle on the scaffolding continued as well, with my fighter eventually grabbing the objective and retreating to the neighboring building. But wait! Valens, one of my opponent’s fighters, had a sling, one of the game’s few ranged weapons. He jumped down from the scaffolding to get a better shot, but ran afoul of the mob in the process. When a gang fighter makes an attack within six inches of a mob, they roll a die to see how they react, as described above. In this case the result was a 5 — they’re angry! They attacked the nearest gang fighter, which unfortunately for me (or very cleverly for my opponent) happened to be one of mine. It hardly seems fair, but angry mobs aren’t known for their discrimination in choosing targets.

In round four I decided that discretion was the better part of winning, so I moved Marcus (holding two objectives) as far away from the action as possible, bravely hidden behind a market stall. In the mean time, the chaos at the building site continued, resulting in two casualties for my side and two objectives for my opponent. As round five began, I realized my mistake in sending Marcus into hiding. While he did hold two objectives, he was also my best fighter and was now too far away from the action to do anything useful. My other remaining fighter made a brave attempt to get at least of my opponent’s objectives, it was not to be.

The game ended with each of us holding two objectives. The scenario didn’t specify a tie breaker, but we decided that since I had suffered two casualties and my opponent only one, she could claim the victory.

Stay tuned for Scenario II: Market Opportunity, in which we fight over loot from a tipped over market stall…