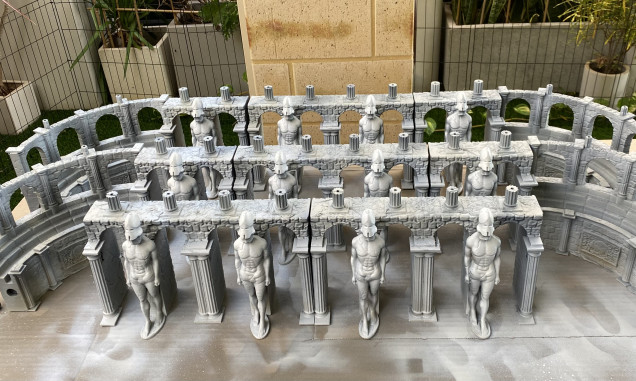

Circus Maximus

A splash of colour.

Although the Circus Maximus was designed for chariot racing, other events were held there, including gladiatorial combats and wild animal hunts, athletic events, and processions. By the time of Augustus, seventy-seven days were given over to public games during the year, and races were run on seventeen of them. There usually were ten or twelve races a day, until Caligula doubled that number, and from the end of his reign, twenty-four races became typical. The number of festivals in which racing occurred also increased, with Circus games instituted in honour of Caligula’s mother and sister, and Tiberius. Still, Domitian once had one hundred races a day but reduced the number of laps to five to fit them all in, and Commodus ran thirty races in just two hours one afternoon in AD 192.

These numbers are exceptional and not likely to have been repeated, if only because the horses had to be transported from the Campus Martius, where they were stabled, over a mile away.

The chariots started from twelve gates (carceres), six on either side of an entrance that led from the Forum Boarium. Above sat the presiding magistrate at whose signal the races began. Far at the other end, along the sweeping curve of the track, was another gate by which processions entered the Circus. In AD 80, it was rebuilt as a triumphal arch to commemorate the conquest of Judea by Titus.

On the spina, itself, were various monuments and shrines, including one to Consus and another to Murcia, who may have been the divinity of the brook over which the Circus was built.

At either end were the metae, or turning posts, comprised of three large gilded bronze cones grouped on a high semicircular base. There were thirteen turns, run counter-clockwise, around the metae for a total of seven laps, a distance of just over three miles.

To ensure a fair start, the starting gates were built along a slight curve so that the distance to the break line, before which the chariots were not allowed to leave their lanes, was the same for each. Drivers were required to stay within a marked lane until that point was reached, after which they could jockey for position. Lots were drawn to determine which gate was selected, and it was from the gates that the race began. The presiding magistrate (either a praetor or consul) dropped a white starting flag, the gates to the stalls flew open, and the race began.

Leave a Reply