PanzerKaput Goes To Barons' War

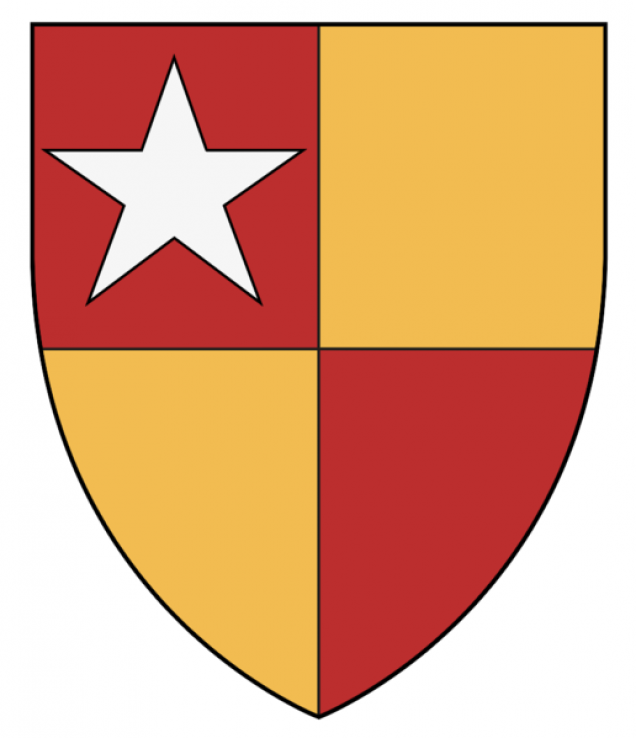

Robert de Vere

Robert de Vere (d. 1221) was a member of a comital family, based at Hedingham (Essex), which owed its rise to rise to eminence to the patronage of the Empress Matilda in the civil war of King Stephen’s reign in the 1140s. Robert himself was the third surviving son of Earl Aubrey (d. 1194) by his third wife, Agnes of Essex, and succeeded to the title on the death of his elder brother, another Aubrey in October 1214. Sometime before Michaelmas 1207 Robert had married Isabel de Bolebec, the aunt and namesake of Earl Aubrey’s wife, who had died childless in 1206 or 1207. Isabel the niece had been the heiress to the Bolebec estate, which was centred on Whitchurch (Bucks.), and her own heirs were her two aunts. Robert’s marriage can therefore be seen as part of a de Vere strategy to retain control over at least half of the Bolebec lands. The de Veres were one of the least well-endowed of the comital families and would have been loath to allow a valuable estate to slip from their grasp.

Robert’s defection to the rebel side in 1215 provides yet another example of King John’s capacity to alienate men who should have been numbered among his natural allies. His predecessor in the title had been one of the king’s most loyal intimates and administrators. Robert was probably moved to defect in part by his resentment at the relief of 1000 marks charged for his entry into his inheritance, which was high for an estate of only moderate extent. Most of all, however, he probably nursed a grievance against the king for his failure to confirm him in the title of earl and in the office of court chamberlain, which de Veres held by hereditary right. Robert is known to have been present at the baronial muster at Stamford in April 1215 and he was named by the chronicler Roger Wendover as one of the principal promoters of discontent. He was a key figure in the East Anglian group of rebels. By 23 June, after the meeting at Runnymede, the king was evidently angling to regain his support because on that date a royal letter was issued which implicitly recognised him as earl of Oxford. By that time, however, it was too late: Robert had already been named to the Twenty Five. Towards the end of March 1216 John took possession of his castle at Hedingham after a three-day siege and the earl, who was not present, was granted a safe-conduct to seek the king’s forgiveness. Within months, however, he had defected to Louis of France and he was not to re-enter royal allegiance for good until the general settlement of the rebellion in the autumn of 1217.

Robert died shortly before 25 October 1221 and was buried in Hatfield Broad Oak priory (Essex). A century after his death, to mark the long-delayed completion of the priory church, a fine tomb effigy to his memory was commissioned, carved by the same sculptors who produced the monument to Aymer de Valence, earl of Pembroke, in Westminster Abbey. At the Dissolution, the effigy was transferred to Hatfield Broad Oak parish church, where it remains. Robert’s widow obtained the guardianship of their son, Hugh, who was a minor, and of his estates, which she was to exercise for about ten years. She died on 3 February 1245 and was buried in the Dominican friary at Oxford, nearer to her own family’s estates.

Leave a Reply