Campaigning through the Ancient and Medieval Worlds

Hengest and Horsa

I wrote this a few years back now, and thought it would fit in with the project, for anyone who is interested in a little bit of the history of the period

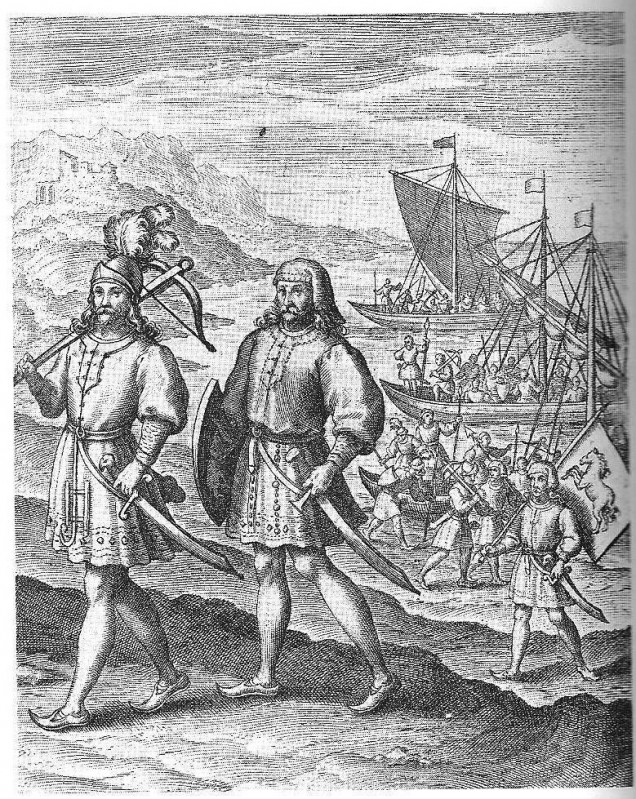

The modern-day county of Kent in the south east of Britain is steeped in the history of Anglo-Saxon England. Famous for the first Anglo-Saxon king to convert to Christianity, and the first written law codes of the English. Its story takes us back to the very first roots of the Anglo-Saxons that dug deep into the very fabric of England’s DNA. Drawing on parallels like other foundation legends such as Rome’s mythical birth story of Romulus and Remus, Kent’s story begins with the arrival of two brothers, Hengist and Horsa. Whether myth or truth, we are blessed that their story is laid out in three of the possibly most critical written narratives that have survived from the Anglo-Saxon period. We will explore their tale and how they managed to gain the very first foothold in England for the Anglo-Saxons.

The first of these sources were written by Bede (d. 735) and is called The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, which he completed in 731. Bede, a monk from Northumbria, gives us our first real insight into the origin story of the kingdom of Kent. Bede recounts how Vortigern, a British leader, invited Germanic tribes to Britain as mercenaries to fight against the raiding Picts. It was at the same time that Marcian became Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire. The date given for this is 449, although Marcian actually became Emperor in 450. In exchange for this service the warriors would be granted lands in the east. The initial wave of warriors that arrived on three ships found Briton so much to their liking they sent word home. More and more warriors began to come. Bede introduces us to our first Anglo-Saxon names, Hengest and Horsa as the leaders. Named as the sons of Wihtgisl, son of Witta, son of Wecta, son of Woden. In this work we discover that Kent was settled by Jutes and that they also established themselves in the Isle of Wight. Hengist would become the more famous of the two brothers. We learn from Bede the danger of battle, with Horsa reaching his end against the Britons.

Almost certainly, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, is the most famous of three sources that deal with Hengist and Horsa. The chronicle was perhaps initially written in the late ninth century, in Wessex, commissioned by Alfred the Great. It concurs with Bede in the initial date for the arrival of Hengist and Horsa as 449. With the chronicle agreeing the year we must presume that either the scribes of the chronicle used Bede as their basis, or that the date is as close as correct as we will be able to conclude. Archaeological evidence in the region can not give us a definitive year as to the transfer of power from Roman to Anglo-Saxon, but do show that by the beginning of six century there had been a movement from one culture to the other. We can also glean more information regarding the ferocious battles the Jutes fought against the Britons in those early days. The chronicle tells us how they fought at, Aylesford in 455 where it states that Horsa died, Crayford in 457, Wippedfleet in 465, and an unnamed place in 473. We also learn from the chronicle that Esc, the believed son of Hengist ‘succeeded to the kingdom’ in the year 488. From this, we can deduce that Hengist would have ruled in Kent until this date and it is probably the year in which he died.

The final of the three sources is the Historia Brittonum and has been attributed by a Welsh monk named Nennius. Nennius’ Welsh origin highlights an entirely different perspective to that of Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. This makes the Historia Brittonum interesting because it was written in the voice of the loser, the Britons who were pushed west by the Anglo-Saxon invasions into modern-day Wales. The Historia Brittonum alludes to more detail of both the families of Hengist and Vortigern and also into the story of how the Jutes gained their foothold on the south-east corner of England. From Nennius we also find out that Hengist’s daughter, who is unnamed, marries Vortigern after Satan had entered his heart. It is like Nennius is looking for an excuse and reason why Vortigern behaved this way, giving away land, and welcoming the primitive un-Christian Germanic tribes to England. He apparently could not have done this on his own, and his mind was now being manipulated by the devil. For his daughter’s hand in marriage, Hengist asked for the whole of Kent, replacing Gwyrangon who ruled there. With more land, Hengist began to invite more and more people to settle in Kent, and their settlements grew. Things though still did not run smoothly, and Vortigern’s son Vortimer fought against Hengist and Horsa, expelling the Jutes back to Thanet, as power and control of Kent see-sawed back and too with numerous battles. Eventually, Hengist plotted to pursue peace. However, it was a trick. Once he had all the senior men of Vortigern in one place, he cried out ‘English, draw your knives.’ This went against the agreed plan that no one would be armed. All three hundred of Vortigern’s men were murdered, and only Vortigern himself was left alive and taken prisoner. Nennius closes the tale by telling us how for his life he had to cede many different districts of the southeastern parts of England, including, Essex, Sussex, and Middlesex and with this, the Anglo-Saxons now indeed had their feet cemented into England’s future.

The Anglo-Saxons would go on to conquer the majority of England and would rule almost undisturbed until the year 1066 when William of Normandy would exterminate the ruling class at the Battle of Hastings, just like Hengist did with Vortigern’s leading men under the illusion of peace. Hengist’s stability in Kent would lead the way for further invasions and settlements of England by the Anglo-Saxons. New foundation stories being reported in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, for new Anglo Saxon kingdoms, such as Aelle of Sussex and Cerdic of Wessex, in the years 477 and 495 retrospectively. The Anglo-Saxons were definitely here to stay.

Bibliography

Brooks, S. & Harrington, S (2010)The Kingdom and People of Kent AD 400-1066: Their History and Archaeology, Stroud, The History Press

Carruthers, B. (2011), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Illustrated and Annotated, Barnsley, Pen & Sword

Hindley, G. (2006) A brief history of the Anglo-Saxons, London, Constable & Robinson

Morris, J (1980), Arthurian Period Sources, Vol. 8 Nennius, British History and The Welsh Annals, London, Phillimore

McClure, J & Collins, R (2008), Bede: The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Venning, T. (2013) The Kings and Queens of Anglo-Saxon England, Stroud, Amberley

Wickham, C. (2010) The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000, London,Penguin

Yorke, B (2013), Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, London, Routledge

Leave a Reply