Operation “Sea Lion” Invading England In 1940? [Part Three]

November 21, 2016 by crew

Good afternoon, Beasts of War. Oriskany here, ready once again to resume our explorations of Operation Sea Lion, Germany’s hypothetical invasion of Great Britain in September, 1940. Through research, theorisation, and wargaming, we hope come up with a prognosis of what this “invasion-that-never-was” might’ve looked like.

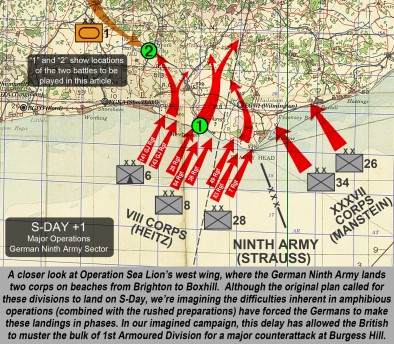

So far, we’ve taken an introductory look at Sea Lion and a cursory view of its prospects in Part One. In Part Two we actually launched the invasion with games depicting German airborne drops and beach landings in Kent, near the town of Folkestone. Now we’ll take a look at what’s happened to the west, along the shores of Sussex.

S-DAY +1

Landings at Newhaven

The date is September 16th, 1940. Initial German landings have been carried off by the Sixteenth Army at Hastings, New Romney, and Folkestone. However, German mines, bombers, and U-boats have failed to completely shut down ferocious Royal Navy counterattacks against the German invasion fleet crossing the English Channel.

Losses have been grievous on both sides. Already two of the Royal Navy’s most powerful battleships, HMS Nelson and Rodney, have been sunk by Luftwaffe bombing, while U-boats have torpedoed HMS Hood off the Isle of Wight. She’s been burning in a massive oil slick for the last eighteen hours.

One British task force, however, built around the battleship HMS Warspite, has broken into the westernmost convoys of the Ninth Army. Many transports carrying the 6th Mountain Division have lost, and the overall Ninth Army landings have been delayed by twenty-four hours. But as dawn rises on S-Day +1, these landings are on again.

As powerful as the Royal Navy was in 1940, one must remember their carrier force was small, and battleships are terribly vulnerable to air and submarine attack. Capital ships like HMS Courageous, Royal Oak, Barham, Prince of Wales, and Repulse, historically all were destroyed by Axis aircraft and submarines early in the war.

Naval actions of World War II teach one immutable truth: The battleship’s day had passed, aircraft and submarines were the new weapons of note. And in 1940, the Royal Navy (particularly the Home Fleet) was a force of battleships, hopelessly prepared for the previous war. If the Germans indeed own the skies over southern England …

Still, it’s tough to ignore this much firepower. This may well have been the death of the Home Fleet’s dreadnoughts, but we have to assume they would have fought like hell to defend their home shores. Thus, we’re imagining that the Home Fleet has weakened and delayed the Sea Lion landings, even if they couldn’t stop them entirely at first.

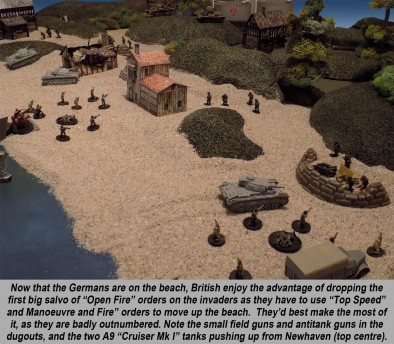

At 06:50 hours on S-Day +1, the German VIII Corps (Ninth Army) hits the beaches, running from Brighton in the west to Beachy Head in the east. In the centre of this attack, the 8th Infantry Division lands at Newhaven. Waiting for them is the under-strength 45th Infantry Division, part of the I Corps commanded by General Harold Alexander.

A solid commander, Alexander has made the best preparations he could. But he’s being hit by three German divisions, while other beaches like Folkestone are only being hit by two.

One reason the Germans are hitting these western beaches with additional forces could be their planned thrust to isolate London from the rest of the country, for which additional forces will be needed in the west. Also, these beaches are out of range of the German coastal artillery batteries at Calais and Boulogne.

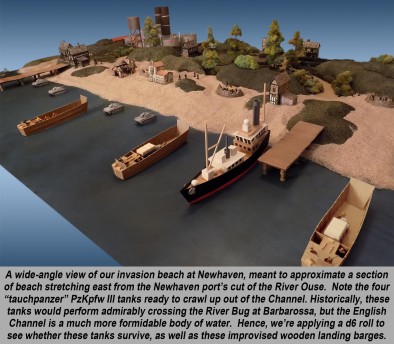

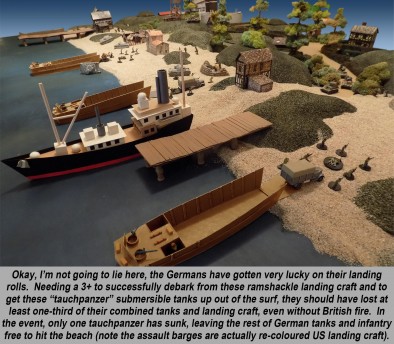

The landings of September 16th are a bloodbath. It’s tough to decide who is more badly prepared, the Germans with their wooden canal barges and hastily-converted “assault ships,” or the British who have little more than sandbags, mines, and some barbed wire to offer as “coastal defences.”

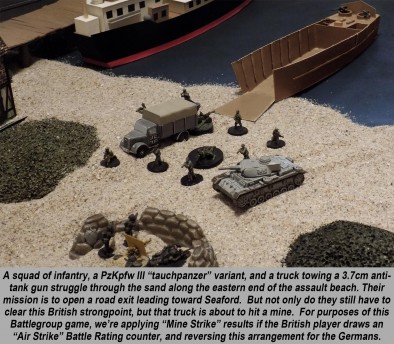

Many of the German “tauchpanzer” submersible tanks don’t perform nearly as well as expected. Although they’ll perform well in river crossings in other theatres, the English Channel is no river. Also, even ancient 18-pounders and underpowered 2-pounder anti-tank guns can easily pop holes in approaching German landing craft.

German heavy equipment also presents a problem. Much of it is still horse-drawn, and horses are not creatures made to endure the pitching and rocking of landing craft, much less when under fire. When the doors finally open, the usually stampede ashore in a panic, often pitching their towed equipment into the surf.

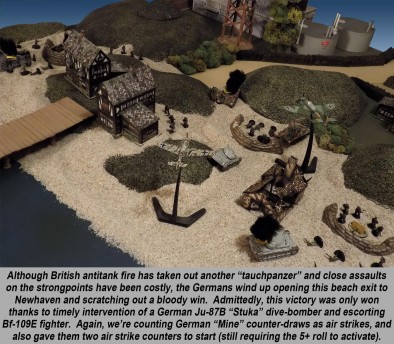

Yet again, it’s the Luftwaffe that saves the day. With Heinkel He-111C, Junkers Ju-88A, and Dornier Do-17 bombers hitting British reserve assembly areas, communication points, and bridges, and Ju-87B Stukas hitting more tactical targets right on the front, the Germans soon claw out just enough of a toehold to secure a tenuous lodgement.

The Luftwaffe, however, is quickly coming to the end of its tether. Simultaneously having to support the landings, sink British battleships and heavy cruisers, and protect the airborne drops from RAF squadrons being re-mustered from bases in the Borderlands and Scotland, endurance of men and machines is rapidly becoming a problem.

S-DAY +3

First Counterstrike

The German 6th Mountain Division just can’t buy a break. Not only do half their transports get sunk by the HMS Warspite trying to cross the Channel, but their weakened landings at Brighton have relegated them to a “flank covering” force for the other divisions of VIII Corps / Ninth Army.

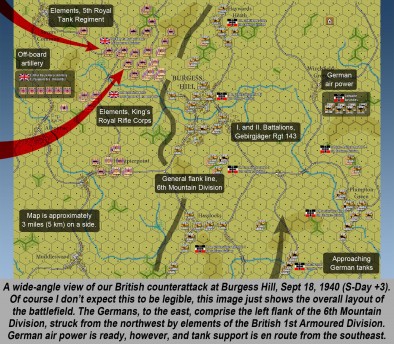

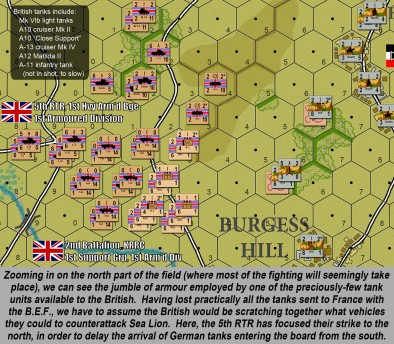

Now, as the VIII Corps pushes its way steadily toward Horsham, Crawley, and Tunbridge Wells, perhaps even a breakthrough toward London and the Thames, the 6th Mountain Division is struck in the left flank by one of the first powerful British counterstrikes of the invasion, mounted by the 1st Armoured Division attacking at Burgess Hill.

By the third day of the invasion, the situation is growing critical for the British. Despite horrendous losses landing from both the air and sea, the Germans have managed to secure the ports of Folkestone, Newhaven, and Eastbourne. Second-wave German divisions are now being debarked in these ports, including two panzer divisions.

Airfields at Hawkinge and Lympe have also been taken, allowing for the fly-in of the German 22nd Air Landing Division. It isn’t all going the Germans’ way, however. A brigade of the 1st London Division, despite being cut off, is holding Dover against all comers, denying the Germans a key port planned for the invasion.

The British realize, however, that they have to strike back now. Accordingly, 1st Armoured Division is given some of Britain’s last tank reserves, reinforced with infantry, and ordered to hit the flank of the German VIII Corps, where the German 6th Mountain Division is braced at the crossroads town of Burgess Hill.

The British have chosen the place for their attack carefully. The 6th Mountain Division lost the better part of a regiment just crossing the Channel, and has had a rough go of its since then. Also, as a mountain division, they’re short of motorized transport, and they’ve been struggling to keep up with the rest of the German advance.

Thus, while the rest of VIII Corps, and especially von Manstein’s XXXVII Corps further east, have been driving north, their flanks become ever more vulnerable as the weakened, exhausted 6th Mountain Division tries to protect Ninth Army’s wing.

Knowing that the Germans will rule the skies, the British reinforce their attack with plenty of antiaircraft batteries. They’ve also been remobilising old stockpiles of 18-pounder howitzers left over from World War I. Far from the newest weapons on the field, they can still lay down plenty of fire support that just might turn the day.

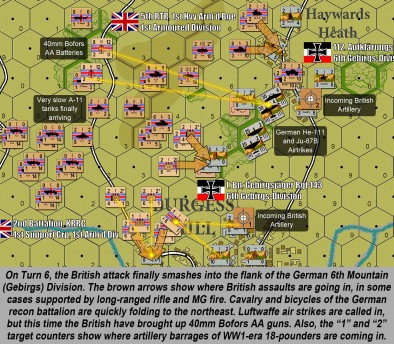

The British launch their attack in the predawn hours, when darkness will still cover their approach from the Luftwaffe. By the time the sun is up fully, the ridges overlooking their advance bristle with 40mm Bofors AA guns. They don’t stop the Stukas entirely, but the Luftwaffe’s impact on this battle is much diminished.

The massed British artillery opens gaps in the sparse German flank protection north or Burgess Hill. The faster Mark VI light tanks, cruiser tanks, and armoured cars race through these breaches, while the slower infantry tanks grind into the German line and support a battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps advancing into Burgess Hill itself.

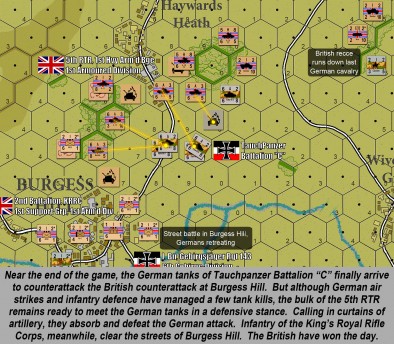

By midday, the flanking regiment of 6th Mountain Division has been badly mauled. Counterattacking German tanks are pinned by British artillery and shot up as they attack dug-in Matildas. To prevent a complete collapse of VIII Corps’ flank, 6th Mountain and 8th Infantry divisions are pulled back, largely halting this part of the German advance.

The British victory at Burgess Hill comes just in time for an embattled Winston Churchill. Remember that he was a compromise choice to replace Neville Chamberlain, who only resigned four months ago. In our timeline the British never won the Battle of Britain, so Churchill is still “Mr. Gallipoli” who has yet to win the confidence of the public.

Accordingly, there’s been a strong faction of Parliament who’s been anxious to cut a deal with the Germans – and they’ve been screaming for Churchill’s resignation practically since the first German soldier landed at Folkestone. In the wake of Burgess Hill, however, these opponents are silenced. Britain...will fight.

But with the spearheads of two German armies now on her shores, now including the lead regiments of two panzer divisions, is it too late? Drop your comments below. Is the tide finally starting to turn? Is German luck at last starting to give out? The fate of Western Europe could hang in the balance!

If you would like to write for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"...we have to assume they would have fought like hell to defend their home shores"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"In the wake of Burgess Hill, however, these opponents are silenced. Britain...will fight"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Amazing series I’ve really liked reading these. It makes me want to dust off my Blitzkreig Germans and see if my friend still has his Early War Brits

Thanks very much, @elessar2590 – I was very interested in the Weekender and XLBS show to see how John and Justin will also be running Sea Lion-themed games in 28mm for Bolt Action. Hey, if even one person / gaming group sets up a game and runs something they haven’t thought about before, my work is done. 😀

Amazing!

It reads like a good book. The political factor is rather intriguing as well..

Can’t wait to read the next instalment!

Thanks, @suetoniuspaullinus – the “narrative” part of the campaign is certainly fun to do, but tricky as well … if only because it can quickly run away with itself and we try to keep these articles to a certain length. I know I said I would last week, but this time I MEAN it … 😀 I will start up that parallel thread in the historical gaming forums (Thursday, most likely) where we can all dump in exposition, background, our own games, photos, and not be limited by length or content type. Then we can really get into the “good… Read more »

I’ve enjoyed reading these, been a particular favourite of mine for years. I would advise anyone who wants to see the view from the German side to read ‘Invasion of England 1940’ by Peter Schenk. Which gives a good idea of just how badly thought out this operation would have been.

Great call, @grizler – Schenk’s writing has in fact been a major (in fact the biggest) source on this series, at least regarding the German planning and orders of battle.

From Part One:

http://www.beastsofwar.com/battlegroup/operation-sea-lion-invading-england-part-one/

This was a really interesting read @oriskany I like the British counterstrike at Burgess Hill. It did go quite as planned I assume. Especially taking into account the fact that they had some knowledge on how to do it after France with Arras being the most spectacular one. Taking into account a lot on AA units was a decisive factor and dug in Matildas is a pain in the bottom. Yet, the attack would be a boost to the morale. So the Brits would have to push further the next day and I wonder if the remains of RAF would… Read more »

I have to admit, @yavasa , I’m completely unfamiliar with the PQ-17 system. I’m assuming this game recreate the PQ-17 Arctic convoy in 1942? What a slaughter that was. And a great example to show what tough time any Royal Navy force would’ve had under German controlled skies. Yes, the British did very well at the Burgess Hill battle. VERY well, in fact, considering. Let’s just say that I’m making no secret about the fact that I’m giving both sides a lot of credit in the course of this Sea Lion campaign. Clearly, we’ve been giving the Germans a lot… Read more »

I couldn’t agree more on Arras @oriskany Yet, some historians tend to show it as an excellent example of a counter strike with the use of tanks. Yet, as you have written it was uncoordinated and conducted with poor equipment. 😉

The approach to this articles that you are writing about with giving credit to both sides is good. If it was hardcore wargaming I don’t believe the counter attack would stand much chances not to mention the whole German landing would be hmm… interesting.

My idea? Whaere what?! I will wait for the next installment 😉

@oriskany As for the PQ-17 just visit GMT Games and search for the game. The rules and some exmples of play are for free. It is not an easy title but really rewarding imho.

Oh, and I’ll check out that PQ-17. COmbined arms WW2 naval wargames are tough. I’ve found that they re often too simplistic (War at Sea, either the Avalon Hill board game or the miniatures A&A game) or too complex (Avalon Hill’s “Flattop”). 😀 Finding something in the “sweet spot” would b e nice, and free is always a good thing! 😀

Thanks, @yavasa – indeed Arras definitely had a big impact, but I think a lot of this came about when Hitler got the reports of what had happened and it reinforced his already-frayed nerves about how far and fast the panzers were advancing without infantry support. He was a World War I veteran, and was used to war a certain speed. The idea of the panzers charging ahead without the infantry always made him (and many of the infantry and artillery trained generals on his staff) very anxious. Battles like Arras seemed to prove to them how reckless the panzer… Read more »

that was a turn up for the books the end of this one series is going to be as predicable as the US elections were with one of the spearheads mauled and half the supply fleet gone ill go 50/50 @oriskany

Thanks, @zorg . I think a big part of what people think about when considering the “possibility of Sea Lion” has to do with whether the Germans can actually make the crossing. As may be apparent from these articles, I think that prospect was actually a lot easier than many people think in the early fall of 1940. It’s what happens AFTER that . . . that’s the killer. It certainly was for the Allies at Normandy. They planned and prepared and planned and prepared for two years for that one incredible day, and then got hung up in the… Read more »

yes the Germans defiantly don’t have the huge supply fleet the allies had in Normandy and will struggle to advance on limited reinforcements/supply’s even with a weakened enemy.

Agreed, @zorg . I think the best chance for a long-tern German victory here is some kind of political collapse or diplomatic solution. But after the British victory at Burgess Hill, that might not be forthcoming . . . 😐

role on Monday for the next instalment to find out. Lol

We’re also starting the support thread in the Historical Gaming forums, @zorg – keep an eye out! 😀

sweet.

What about the Royal Navy destroyers and smaller MTB’s of which they had a lot. Do they not play a part yet ? Or are they waiting in the wings to cut off supplies. The Luftwaffe had a pretty bad track record when it came to targetting Naval craft.

Great questions, @huscarle ~ I’ve just checked my records and I show 34 destroyers with the Home Fleet in September, 1940, 11 of which were under repair (I’ll get their names together in a list later on). So that’s 23 operational destroyers. Not a lot, I don’t think, against some 4000 (admittedly *unarmed*) German transports and “landing craft.” I think this is especially true considering that many of these destroyers would still be required to keep the convoy system going with the United States and the British trade empire. The plight of the Royal Navy vis-a-vis destroyers can be inferred… Read more »

What about the Kriegsmarine which took heavy losses in the Norway campaign over half of the Destroyer fleet and some Cruisers were lost. They weren’t left with a lot that wasn’t in for repair at the time. The biggest threat will be the U Boats for sure. The Luftwaffe unlike other Air forces made little use of torpedo’s and lacked A.P. bombs hence their bad strike rate against shipping. I’m glad to see they have overcome these difficulties and made it ashore as the land campaign is what we all want to see played out. The German Army is another… Read more »

Great point, re: the German surface fleet, @huscarle – the German surface fleet in the 1940 Sea Lion plans are basically a non-issue, at least so far in the plans and documentation I can find. Indeed about half the Kriegsmarine’s surface assets were lost or at least heavily damaged during Operation Weserübung. None of the “famous” heavy ships (Bismarck, Tirpitz, etc) were ready in the fall of 1940. From what I can find, all the remaining surface units were either being held back or sent out into the open Atlantic to . . . and I’m not kidding here .… Read more »

True Battleships are ineffective when it comes to the right weaponry. Despite having cracked the German codes. I believe the RN would have responded in part to the ruse to draw them away into the Atlantic. To not respond would have alerted the Germans to the fact that we were party to their communications which in long run have been far more costly. This was a pretence which was played throughout the war. We always used the information gathered from the code breakers carefully. Not giving the game away was a priority. Using the info from Bletchley often required creating… Read more »

@huscarle – I would agree that deliberately “ignoring” intelligence is sometimes undertaken so as to not tip your hand than you’re reading the enemy’s mail. The famous (or should I say infamous) example of this is the terror-bombing of Coventry. I’ve read accounts that claim the British knew this was coming and took no steps to defend or evacuate the town, these lives were “deliberately sacrificed” to preserve the Enigma / ULTRA secret. I would offer the following: As with many presumed factors or actions undertaken by the British predicted for a a Sea Lion scenario, logic is often skewed… Read more »

Another great article and more great photos. That trawler sitting by the dock was built totally from scratch in like 2 hrs! Just to put some decoration on the table.

Well worth the effort. Tables should always look cool

Thanks very much @gladesrunner and @huscarle – Ahh . . . actually that was about three hours. And after that game I put about another two hours into it to really finish it off (and enter it in Chris Goddard’s November Competition –

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/painting/forum/topic/november-painting-competition-is-now-open/

So it actually looks a little better now than it did on this table (sadly). 🙂

Quite an interesting read @oriskany. If the RN Home Fleet cant impale itself on the spears of the enemy, then what was it good for. At this stage of the invasion I see it as now or never for the RN and those extremely expensive dreadnoughts just become expendable. At this stage of the war the 2 pounders and 37mm AT guns that are almost laughable later in the war are remarkably potent at this stage of the war and most German tanks will not get a second chance with the 2 pounders. The Royal Artillery training is almost second… Read more »

Thanks @jamesevans140 – Reading what you sayabout the RN “impaling itself,” I’m reminded of the plans the Japanese had for their battleship Yamato at Okinawa. Only enough fuel for a one-way voyage, no escorts . . . just beach yourself next to the American invasion beaches . . . you CAN’T be sunk now, and fire those 18-inch guns until the ammo runs out . . . I agree 2-pounders are no joke against armor of the period. With a close range penetration of out to 20″ . . .they have at least a 50-50 chance of penetrating just a… Read more »

I love these historical “What if’s”. I do wonder about Operation Sealion though if they had tried the “First Sea Lord Jack Fisher Manoeuvre”. Fisher had put forward a plan during his tenure as First Sea Lord during WWI of an amphibious assault of Germany through the Baltic Sea after grounding a number of big gunned cruisers to act as fire support. Once grounded they would be unsinkable and were the most likely way for troops to survive the trip to the beach in great numbers. Once there the troops (about 4 divisions) would spread out and would require far… Read more »

Thanks, @horus500 – now THAT’s an awesome mental image, the Graf Zeppelin completed and loaded not with aircraft, but hundreds of tanks – big ones too (at least for the time) – PzKpfw IIIs and IVs. Maybe even a handful of those early B- and C- model StuGs! 😀 Landing on the Baltic coast? That’s a rough ride in World War 1 – you have to get right past the sizable German Navy (in those days). They’ve just completed construction / enlargement on the Kiel Canal (I’ve read some people call THIS one of the contributing factors to starting WW1)… Read more »

Another great read. I posted up a link on the FB page. But you should check out the documentary called. “It Happened Here” Filmed in 1964 it covers life in an occupied England.

Would be cool for some skirmish game ideas.

@commissarmoody – thanks very much, and thanks for the Facebook link. More exposure is always a great thing for an article series like this!

Skirmish games in occupied England is a subject I think @jamesevans140 will be covering in more detail (I can only add so much in limited space). But I’ll definitely keep an eye out for the documentary. I just watched “Hitler’s Britain” which was okay, but not great.

Hitler’s Britain was ok. I know you folks can nitpick just about any history or what if scenario to death. But its ok for a starter. The same guys who did “It happened here” also did a documentary in 63-64 exposing pretty much how ill prepared the government was to deal with a full on nuclear war. It was band by the BBC if memory serves. “It happened here” fallows a lady who was a Nurse prewar and the problems she had to deal with getting reregistered with the new government. The new rules. trying to just get along as… Read more »

@commissarmoody – Actually found It happened here on Youtube yesterday and gave it a watch. Didn’t get through all of it yet, but it was definitely pretty good. 😀 Great recommendation, thanks! 😀

Glad to hear you are enjoying it. As I said, its not for every one. But I think its a good start for those who want to do an occupied Britain style game.

Indeed, @commissarmoody – I definitely prefer the approach taken by “It Happened Here” it to a “Hitler’s Britain” approach. At least the version I see on YouTube and Netflix – Hitler’s Britain immediately goes for the huge CG red swastika banners hanging off Big Ben and Westminster . . . immediately going for that emotionalist gut reaction. I dunno, just not for me. In fact, when @lancorz was working up some of the banner graphics for this article series, I asked him specifically to avoid this kind of thing. (1) – who wants swastikas sprawled all over Beasts of War,… Read more »

Let’s face it @oriskany unless those dreads do something they are nothing but anchors of defeat. While others in the RN and government would be screaming that they might be WW1 relics but they will not be paid off for another 20 years so be careful with them. Expanding on your Yamato scenario there are plenty of mud flats in your invasion areas where these dinosaurs could be put to useful rest. In our Finnish wars of this period we have become very respectful of the Swedish and German 37mm guns and sidestepping that 88 style son of a gun… Read more »

Great comment, @jamesevans140 – I agree that these battleships are pretty much doomed, unless they’re not used (which I highly doubt). Still, the mental imagery of just one of these things loose in the middle of a largely wooden German invasion fleet is a deliciously horrible glory. Okay, I’m looking at (Sept 6, 1940) – in the Home Fleet: 1st Battle Squadron BB 26 HMS Nelson BB 29 HMS Rodney (just completing turbine blade repair) BB 04 HMS Barham Battle Cruiser Squadron BC 51 HMS Hood BC 34 HMS Repulse 1st Cruiser Squadron CA 39 Devonshire CA D84 HMAS Australia… Read more »

As always a joy to read, enjoy your thanksgiving

Thanks, @rasmus ! 😀 Have a great holiday (some long-overdue time off coming up . . . ) 😀

Really enjoyed the first two articles but had been looking forward to how the boys from Sussex performed when their turn came. Good to see that they put up a fight! The tricky part with any beach landings along the Sussex coast is the hill line just inland (South Downs). This reaches the sea in parts, Beachy Head being a good example of a formidable chalk cliff akin to Dover. The South Downs would present any landing army a tough struggle having just landed. Given the scenario, I would imagine that the Germans would have pushed over this, especially given… Read more »

Thanks, @redvers – but you’ll remember I apologized in advance if I blew up up house! 😀 Sadly, I had to cut it off a little for reasons of space, but the hex maps I had set up for some of the earlier battles really do have a line of hills along its north edge. I didn’t know the name of South Downs, but these hills (I think) are in there, based on information I can find on Google Earth and the like. These hills have a big impact in Panzer Leader games, for reasons of LOS, spotting, movement penalties,… Read more »

You did indeed apologise up front. And from the game you played, it was more likely the British artillery that would have done the damage rather than the invading Germans. I think the line of hills on the north of your map that you cut off aren’t far enough north. The one you refer to is just a rise from the ‘low weald’ to the ‘high weald’ in Sussex. The North Downs run east to west about 20 to 30 miles north of Burgess Hill. The South Downs, just to the south of the village of Hassocks in your battle,… Read more »

That my bad, @redvers – I checked my files and this line of “northern hills” I think I was looking at Ashford over in Kent. I don’t know of those are the same hills you’re talking about (i.e., if “North Downs” runs that far east). So far the only brown slop hexes (in Panzer Leader) that have really been in a position to make a difference have been the bluffs immediately behind Folkestone. Those have been murder, just as they are when you play Gold or Omaha in Normandy (but not, say . . . Juno, Sword, or Utah). Anyway,… Read more »

I didn’t realise that these were custom drawn maps. Extra kudos to you for that. They’re pretty accurate and probably about right for 1940’s Sussex – even more kudos for getting it that close when you’re aiming from the other side of the Atlantic. Not sure where you get the time to put all the effort in! And yes, the hills North of Ashford are the North Downs that, having skirted the south of Croydon, then turn South East and head down to the coast. The white cliffs of Dover is where they meet the sea. Of course, any British… Read more »

Thanks, @redvers – yes, custom drawn maps, BUT . . . I have a library of template files and components I’ve steadily built up in Photoshop so it’s not quite as horrific as it sounds. And the “point-point” cartography (ahem) DOES admittedly compromise with game mechanics and the templates in place.

Great series of articles. Very tempting to play a game of London as Stalingrad… I’m not sure the old dreadnoughts would have been sunk so easily, especially Rodney and Nelson. I would accept their weakness against U-Boats, but German air power had limited ability to sink battle ships. They had no torpedo bombers, which were a key aspect to Japan’s success in the pacific. (Italy had them, and as their efforts in the battle of Britain, showed, Italian air power was pretty feeble). I would argue the deck armour plating of RN capital ships was fairly substantial, and German bombers… Read more »

Thanks very much, @rjparker – you make some great points n the British dreadnaughts. A few posts above I have their listed names in the Home Fleet in September 1941. Three battleships (one of them very old) and two battlecruisers. The more I look at this, the more I think the “heroes” of the Royal Navy in this scenario may have been the cruisers. The Battleships are just too vulnerable to U-boat attack (point taken about the aircraft). The destroyers are too few, and trying to either protect convoy routes or the aforementioned capital ships against U-boats. British carriers are… Read more »

oriskany

What a great article series, We both enjoyed reading it and the pictures really add the flavour.

Chris G and Victoria

Thanks very much, @chrisg and @victoriag ! 🙂

I have been thinking @oriskany perhaps like a bar room fight it is the little guy you have to keep your eye on. In this case the motor torpedo boats. Look at the carnage the German E-Boats caused when they got in amongst the U.S. practice invasion exercise. Also a Ju-88 doing a torpedo run would not try to run then down and they are too agile for a Ju-87 to dive bomb. The MTBs would carve up the tugs pulling the landing barges or any of the motorised one for that matter. The 75mm IG18 and the 37mm PaK36… Read more »

@jamesevans140 – “A bar room fight it is the little guy you have to keep your eye on. In this case the motor torpedo boats.” — I’m coming around to that as well. That, and the cruisers. Were you still thinking of a War at Sea scenario in the channel? Chris Goddard I think was the one toying with the idea of an MBT – E-boat “skirmish.” 😀 The 7.5 cm IGs work so much better for me in Panzer Leader. They only have a 2 attack factor but a 12 range, which means that 2 AF doubles to 4… Read more »

oriskany

chrisg is a sleep. i will let him know 🙂

Cool deal. Thanks! 😀

We are thinking about a WaS games @oriskany for Operation Sea Lion. One issue is that While we have respectable U.S. and Japanese Fleets our U.K. and German fleets are fairly poor, just enough for a 100 points battle. If we were to do a series of games it would be to effect what is landed in the beaches. For our current look at the Home Guard we are going to use your articles for the background story and so to that end it will be you telling us what arrived. Certainly later if we wished to do our own… Read more »

@jamesevans140 – It’s tempting to imagine British battleships beaching themselves right next to German invasion beaches or even “running the gauntlet” and drawing all the fire so cruisers, destroyers, and even MBTs could whisk in and start sinking German transports. It might even be fun trying it out in a wargame. But I don’t think the British would have tried this. A completely subjective guess here. But the British public and especially Navy officer class really cherished these things. The Germans bombed Westminster Abbey and the British shrugged it off. They practically leveled Coventry in one of the worst terror-bombings… Read more »

@Oriskany, just a bit further on my previous comments about Germany’s drawing the British fleet into a decisive action in the Channel or North Sea. It’s easy to assume that the battle would go Britain’s way because we look at the fleets available at the time and assume it’s a numbers game. Germany doesn’t have the Tirpitz and Bismarck yet so they will lose and quickly. What is worth remembering is that less than 20 years previous Brigadier General Billy Mitchell sunk a battleship and was ultimately humiliated and court-marshaled for demonstrating the fact that you got thousands of planes… Read more »

@horus500 – okay, my bad. We’re talking about a possible British offensive on German shores in WW2, I thought we were talking about WW1 (hence, Jackie Fisher, etc) While I certainly can’t argue with the possibility, I don’t think that would have happened but ONLY for political reasons. British strategic thinking at the time was focused on peripheral landings all over the place . . . Sicily, Italy (which they did, obviously), but they also wanted landings in Greece, Yugoslavia, Sardinia, Norway, every place EXCEPT northwest Europe. We can’t forget how desperately and bitterly Churchill opposed the landings in France… Read more »

@oriskany Just had time to read parts 2 and 3, and they are a great ‘what if’ bit of reading and gaming, with some fabulous tabletop shots. Well done, as always!

Awesome, @cpauls1 – thanks very much! 😀

I don’t remember, do you guys celebrate Thanksgiving tomorrow? If so, have a great holiday! 😀

This scenario does make for great wargaming as it is a battle and a raid within the same game. Too true about British public opinion. Indeed if a person brought me a business plan with the same parameters as this scenario I would reject it out of hand as an act of desperation. There is great investment for only a small temporary gain at best case. But there is the a danger if the plan were presented the Churchill. He has a propensity to risky daring do plans and the RN loves Churchill. The plan would most likely to fail… Read more »

That’s one of the great things about World War 2 from a gaming perspective . . . things change so fast that these special rules don’t have a chance to “pile up” too deep. Yes, we start stacking up special rules for 3.7cm PaKs and their HE ammunition, L56 8.8cm, the 122mm on the JS 2 and 3 tanks, etc. But I can’t imagine a scenario where a 3.7cm is standing next to a Tiger, except in an AA role on the back of a halftrack. So in any given scenario, you don’t have to work in too many special… Read more »

That was one great things about many map based games of the period is that they kept most special rules to the scenario brief that allowed very specific fine tuning for a specific battle. Yes they were many games that had round type and numbers. We used the GHQ rules for moderns 1:300 where we used platoons and company of tanks where round management seriously slowed down the game. We did not think much of it at the time as all wargames took a better part of the day and large games took multiple days. Today people want several games… Read more »

Oh, absolutely (on the 37mm FlaK with Tigers). 20mm, 37mm, and 20mm quad AA systems used as HE on enemy infantry is one of the most fun things to do in Panzer Leader.

Well, that and fire a “Wespe” or “Hummel” direct-fire into an enemy-held urban hex. BIGGA-Boom! 😀

Ohh Yeah!!!!

Back scratching at its best.

I am amazed that so many players talk about combined arms but rarely to I see it on the table Pared teams can be devastating.

Honestly I’m not sure if many of the game we see nowadays are big enough or deep enough to demand that kind of combined arms work. Battlegroup is a sure exception, but I’m sure people are used to me schilling for that game. Well, this is just one of the many reasons. Same with Panzer Leader. You can’t just stack up on big cats and expect to win. Heck, look at that fallschirmjaeger game we just finished in the Sea Lion thread. The best infantry in the game until 1945 USMC assault infantry, and the Germans lose because that’s ALL… Read more »