The Battle Of Midway 75th Anniversary: Turning Point In The Pacific [Part Two]

May 29, 2017 by oriskany

Welcome back, one and all, to our commemorative article series marking the 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Midway. We’re not only looking at this epic naval battle from a historical perspective, but also through the “gaming eyes” of Hendrik Jan Seijmonsbergen’s (@ecclesiastes) “Naval War” miniatures system.

The Battle of Midway was a decisive naval battle fought between the United States and the Japanese Empire in early June, 1942. In Part One, we introduced the Naval War system, sketched out the background of the Pacific War, and looked at both sides’ planning as the Battle of Midway began to take shape.

But now, it’s time to “weigh anchor and raise steam” … and set a course into the maelstrom of this historic battle.

Initial Approaches

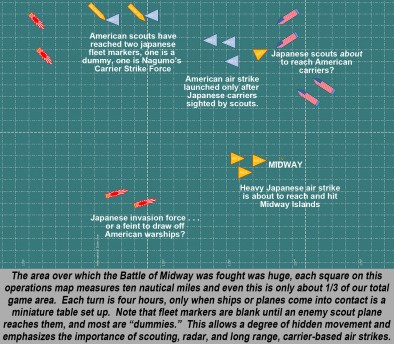

As discussed in Part One, the Japanese plan was to launch invasions at the Midway Atoll in the central Pacific and the Aleutian Islands off the coast of Alaska. When the Americans responded, perhaps dividing their all-important aircraft carriers between the two threats, the more numerous Japanese would ambush and destroy them forever.

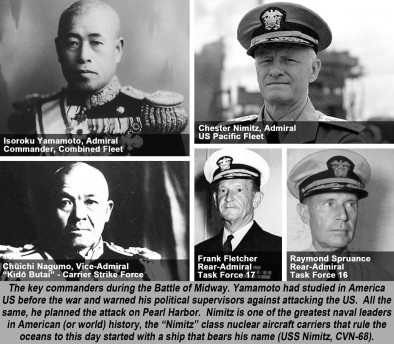

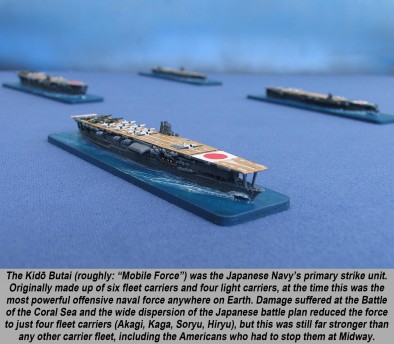

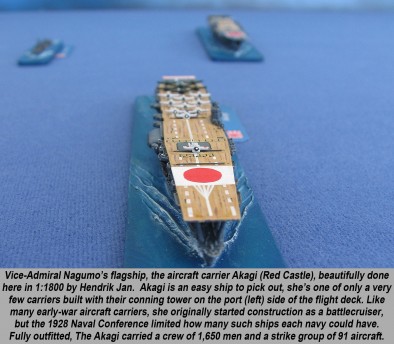

In overall command was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, naval mastermind behind the attack on Pearl Harbor. Commanding the main Japanese carrier strike force would be Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo. This was the heart of the Japanese Navy’s offensive power, built around the huge aircraft carriers Akagi, Kaga, Sōryu, and Hiryū.

Outgunning the American Pacific Fleet perhaps three-to-one, the Japanese were supremely confident. In fact, the only flaw most Japanese admirals saw in their plan was that the possibility that the Americans might not come out and fight at all, faced with such an obviously superior force.

Although badly outnumbered, the Americans had broken Japanese naval codes and knew every move the Japanese were making. Under the overall command of Admiral Chester Nimitz, the Americans thus knew to ignore the bait of the Aleutians landings, and instead concentrate everything on counter-ambushing the Japanese at Midway.

The Americans thus divided their aircraft carriers into two main groups. First of these was Task Force 16, built around the carriers Enterprise and Hornet, under the command of Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. The hastily-repaired carrier Yorktown formed the heart of Task Force 17, under Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher.

Task Force 16 left the base at Pearl Harbor first, while Yorktown left two days later. Repair crews were still on-board, welding together damage suffered in the Battle of the Coral Sea in May. The two task forces would meet up at “Point Luck,” a spot in the Pacific about 325 nautical miles northeast of Midway.

Despite their vast numerical superiority, important parts of the Japanese plan were already coming apart. First off, the screen of submarines they stationed west of Pearl Harbor to report the departure of the American carriers arrived too late. Forewarned of Japanese plans, the American carriers had already left.

The Japanese carriers sailed on May 27th. On the next day, the Aleutian and Midway invasion forces also put to sea. Finally, on May 29th Yamamoto’s main force of battleships and heavy cruisers sortied. Hundreds of warships were now in motion, sailing from different bases far across the Pacific. The complex Japanese plan had been launched.

First Strikes

The Aleutian invasion force reached their targets in the far north of the Pacific, landing Japanese marines on the islands of Attu and Kiska, starting on June 3rd, 1942. Although these landings were successful and the islands captured, they failed to lure the American carrier fleet away from Midway, some 1,600 miles to the south.

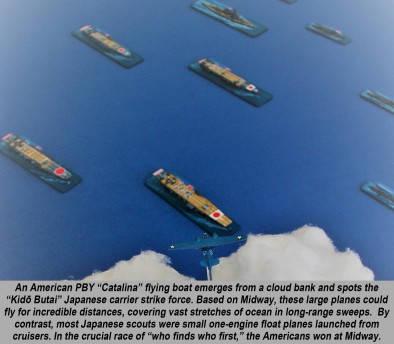

Meanwhile, Nagumo’s powerful carrier strike force was closing on Midway from the northwest. Although the Americans knew the approximate direction and date of the attack, they still had to actually FIND the Japanese. Thus, both sides began launching scout planes, each task force attempting to find the other.

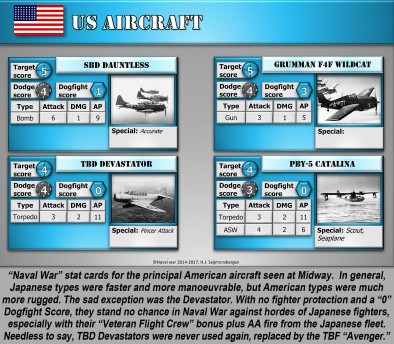

In this search effort, the Americans had a distinct advantage. Based on Midway, big PBY “Catalina” seaplanes could sweep much larger tracks of ocean than small Japanese float planes usually launched from cruisers or battleships. The Japanese search pattern was also very thin, thanks in part to mechanical failures in some of the search planes.

The end result was that the Americans found the Japanese first, with the main body sighted around 09:30 on June 3rd. B-17 “Flying Fortress” bombers were launched from Midway to bomb the Japanese (still 700 miles away), but the big four-engine bombers were unable to hit any Japanese ships in their high-altitude runs.

Nagumo knew he’d been spotted (and now attacked), but by LAND-based planes. He still had no idea American carriers were about, and so started preparations for a massive air strike on the Island of Midway itself.

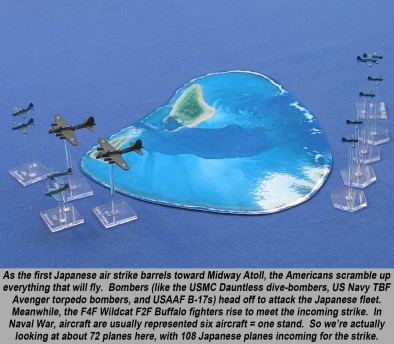

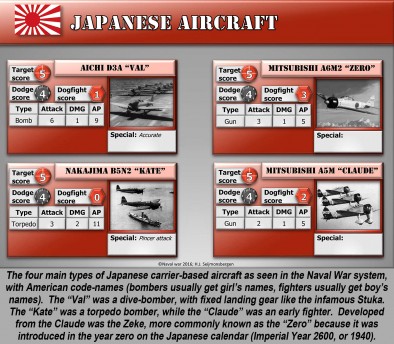

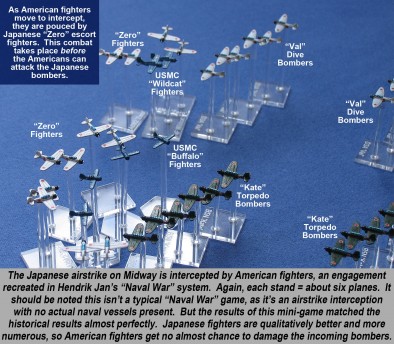

The next morning (June 4th), the four Japanese carriers struck Midway with over a hundred aircraft. US Marine Corps fighter pilots stationed on the island did they best they could, but they were heavily outnumbered and flying mostly outdated F2F “Buffalo” type fighter planes.

Yet despite heavy damage to Midway’s airfields, Midway had already launched more Navy, Marine Corps, and Army Air Force bombers for another attack on the Japanese carrier force. The result was a slaughter, with terrible losses sustained by the American planes without a single Japanese ship being hit by bombs or torpedoes.

The first Marine pilot to go down was Major Lofton Henderson, leading Squadron VMSB-241 in an attack on the aircraft carrier Hiryū. He was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross, and “Henderson Field” was named after him on Guadalcanal. One badly-damaged Army B-26 bomber also tried to crash into Nagumo’s bridge, barely missing.

Fatal Decisions

It was clear to Nagumo that despite the mauling they had received, the Americans on Midway still posed a lethal threat. Accordingly, he ordered his carriers to prepare the remainder of his planes for another strike. Meanwhile, his first strike wave was just returning, and urgently needed to land before they ran out of fuel.

At this precise moment, however, a scout plane from the cruiser Tone reported that it had sighted a collection of American ships, but didn’t say what kind. The flight and hangar decks of Nagumo’s carriers became more crowded as preparations for the second strike continued. Perhaps forty minutes later, another message came in...

“American force is accompanied by what appears to be an aircraft carrier.”

Nagumo now had one hell of a problem. His orders were to sink American aircraft carriers (the whole point of the Midway operation), which posed an even bigger threat than Midway. But his flight decks were crammed with planes loaded for a LAND strike, armed with contact bombs instead of armour-piercing bombs and torpedoes.

The flight and hangar decks were in chaos as the carriers tried to recover the planes of the first Midway strike, then prepare a second full-strength strike at Midway, only to have these orders changed for a naval strike against American warships. Each of these tasks takes a carrier hangar crew (hundreds of men) about an hour to prepare.

In a frantic attempt to do execute these three tasks almost at once, the Japanese carrier crews slaved at top speed. As orders were passed down to arm the planes for shipping strikes, then land strikes, then shipping strikes again, ordinance was left stacked up on the hangar and flight decks instead of being safely stored in the ships’ magazines.

Nagumo, meanwhile, wasn’t the only one facing deadly choices during the fateful morning hours of June 4th. Since the Japanese carriers were first spotted about twenty-four hours ago, the carriers Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown had been making top speed to close the distance in a desperate effort to get in that all important first strike.

Being outnumbered, the Americans HAD to hit the Japanese first. A first strike, with a little luck, just MIGHT cripple one or two Japanese carriers and even the odds. Thus we see the desperate, unescorted, and tragically doomed bomber strikes from Midway Island on the morning of June 4th.

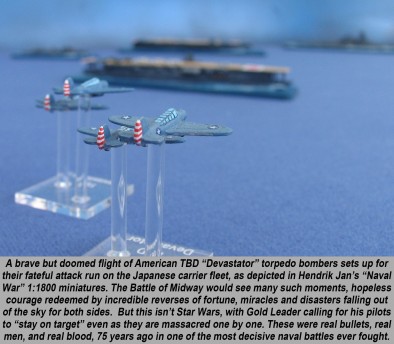

As grim reports of these missions came in, the American carriers now launched their own strikes. They still weren’t quite close enough for some of their older TBD “Devastator” torpedo bombers to make it back before their fuel ran out. They were launched anyway…on a one-way mission.

Everything went wrong for the Americans. In their haste to launch a first strike against the Japanese carriers, the fighters, torpedo bombers, and dive bombers were not massed into a single strike that headed toward the Japanese all at once. Remember it takes at least half an hour to get all these planes in the air, that’s thirty minutes of fuel.

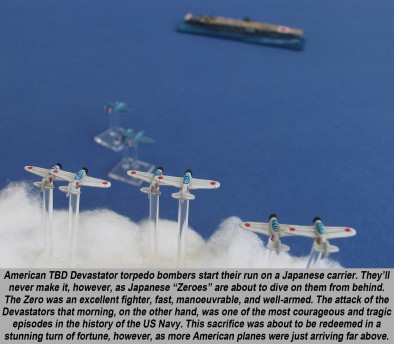

Thus, the American strike force flew out in patches, along different vectors. Many got lost. They did not arrive over the target together. When the TBD “Devastators” arrived, they had no fighter cover. Already past the point of no return on fuel and flying tragically obsolete aircraft, they more or less knew they were doomed…

They attacked the Japanese fleet anyway.

The hail of anti-aircraft fire from dozens of huge Japanese warships was incredible. Meanwhile, nimble “Zero” fighter planes also ravaged the lumbering torpedo bombers as they struggled to come in on shallow, flat attack runs to drop torpedoes in the water toward the Japanese ships.

The results were as horrific as they were predictable. Every single Devastator torpedo bomber was shot down. Each plane had two men aboard, and only one man survived from the entire force (rescued later from the water). Not a single hit was scored on a Japanese warship.

Miracle In The Making?

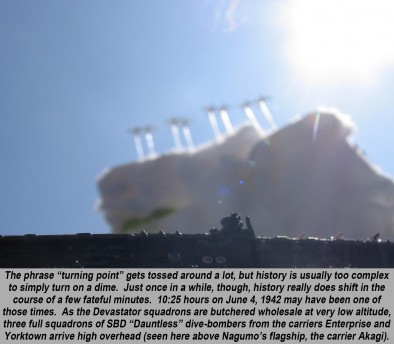

However, the grisly massacre of the Devastators had, in an ironic twist, left the Japanese carrier fleet completely exposed to a new threat. A force of SBD “Dauntless” dive-bombers from the carriers Enterprise and Yorktown, previously lost, just happened to re-find their bearings and arrive over the Japanese fleet at just that very moment.

These dive-bombers arrived at high altitude, mostly from the northeast. The Zero fighters were all at low level, tearing apart the luckless torpedo bombers to the southwest. Below the American dive-bombers was the entire Japanese fleet, exposed and unaware, their hangars packed with extra ordinance and fuelled warplanes.

What would follow would be five of the most decisive minutes in the history of naval warfare.

We hope you’ll join us next week for Part Three of our look at the Battle of Midway. As you can see, things are about to kick off in a really big way. Meanwhile, we hope you enjoyed the article, and will post your comments and questions below!

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"But now, it’s time to “weigh anchor and raise steam" and set a course into the maelstrom of this historic battle..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Already past the point of no return on fuel and flying tragically obsolete aircraft, they more or less knew they were doomed [...] they attacked the Japanese fleet anyway..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

![TerrainFest 2024! Build Terrain With OnTableTop & Win A £300 Prize [Extended!]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2024/10/TerrainFEST-2024-Social-Media-Post-Square-225-127.jpg)

Excellent as ever. Have enjoyed stories about Midway ever since reading about it in a comic book back in the 60’s. Looking forward to reading about Charlton Heston’s part in the battle.

The ship models are brilliant, are they scratch built or retail? Roll on part 3.

Thanks, @gremlin . 😀 Ah, good ole’ Charleston Heston. He plays a fictional character in the movie, that I think takes part in the strike against the carrier Hiryu. We get to that in Part 04.

Except this time it’s the crew of the Hiryu who have to yell that iconic line:

You blew it up, Charleton Heston! You maniacs! Damn you! Damn you all to hell!

😀 😀 😀

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sPbjPOgRtyA

@gremlin The ship mini’s are a combination of Shapeways 3D printed models (mainly from Tiny Thingamajigs’ shop https://www.shapeways.com/shops/tinythingamajigs) and repainted Axis & Allies War at Sea miniatures.

I still say that @ecclesiates ‘ last photo in this article, of those SBD Dauntlesses coming out of the sun above Akagi is one of the best wargaming table photos every taken – full friggin’ stop – cut, dry, the end. 😀 When he proposed this as a “cliffhanger” photo to Part 02 leading into Part 03, I thought it was genius. 😀

I have to agree…that is a great photo! At first glance I thought he took his mini to an air show and had fantastic timing with the camera!

The lens flare is great. 😀

Agreed. That’s a really purty picture.

Any chance of seeing how it was done? Scratching my head as to how he got down so low with such small models.

I didn’t take a picture of me taking a picture ofcourse 🙂

The model was balanced at the very edge of the table (even hanging over a bit, holding my breath) and I took the shot from the ground looking up at the sun and the dive-bombers past the ship. I really had that shot in my mind for a while and it took some waiting for a clear sunny day to make it happen 🙂

I figured it might be something like that.

Great idea and a good execution. Not often we see that in our hobby. 🙂

This probably goes without saying, but just in case …

Users can click on any of these images to expand, then right click to “Open Image in New Tab” (the command in Chrome, I’m sure in other browsers the command is similar) to open the image in its full 1920p size and resolution. 😀

Brilliant stuff!

Thanks, @dawfydd ! 😀

Fantastic stuff, thanks for the write-up, and to @ecclesiastes for the pictorial accompaniment.

Thanks, @evilstu – and I second the thought re: @ecclesieastes ‘ photos. Couldn’t have done this article series without it, or at the very most, it would have just been photos of counters on a grid and historical images. 🙂

Great stuff, while I have seen a number of documentaries on the battle. I like getting it down in games height

Thanks very much, @rasmus – I agree the wargames angle is critical, especially when publishing on Beasts of War. After all, I can write history for years, but without that connection to a wargame, it;s just a class where many of us used to fall asleep in our younger days. 😀

I think if more history teachers presented history in terms of a war game, less of those students would be falling asleep. I know I now feel a little more comfortable talking about the battle and I am NOT a “history buff”

Well, there’s always Simulating War by Phillip Sabin – where he discusses teaching through wargames.

A little pretentious, but still a great read.

https://www.amazon.com/Simulating-War-Studying-Conflict-Simulation/dp/1472533917

I love how clearly you broke down the events leading up to the day and the day itself. Also, the pictures really help tell the tale. However, it’s your captions that really tie it all together for me. They give great information that might have weighed down the article if squeezed in and while highlighting the great shots and @ecclesiastes gaming efforts.

Looking forward to the next part.

Thanks, @gladesrunner – Captions are the “secret sauce” to an Oriskany article. Of the other writers who’ve contributed articles, I’ve only seen one put in captions. They’re required to “place” the image in the article and tie in with context. Plus, I can squeeze in more words that way. 😀

Read Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway

Book by Jonathan B. Parshall

the miracle 5 minutes explained,,,,,it wasn’t a miracle and it wasn’t 5 minutes. Buying into the account by Fuchida to explain away the failure of the japanese at midway.

Read it. Maybe we should wait until Part 03, when we get the segment of the battle you’re talking about, you’re talking about before you start picking apart our work.

So far, the article is great. Far too few historical games covered and just finished a Leyte Gulf 1944 game ( article is coming )

You’re writing an article on Leyte Gulf? That that sounds interesting. 😀 My only thought is, are you covering the whole battle in one article? Or a series?

Once again I’ve negligent in getting to this series, and I do apologize. I suppose I have better than a layman’s understanding of the battle, and could once rattle off the names of the carriers on both sides, but it’s always good to see a new take on this pivotal battle, and the gorgeous models of course! The outside armchair arguments I could do without (and a major reason why I steer clear of gaming historical conflicts), but that aside, wonderful work @oriskany , and beautiful models @ecclesiates . Love the photo! Well done to both of you! 🙂 @gladesrunner… Read more »

Thanks, @cpauls1 . 😀

I agree that “armchair arguments” are annoying, but as you say, they are part and parcel of historical wargaming. And since they’re wargames (and not recreations or reenactments) I feel they have to have at least a little “what if” opportunity for players to try different solutions to the tactical or operational problems at hand.

And besides, as BoW Historical Editor, it’s kind of my “job.” 🙂

Glad you liked the article!

Always enjoy your historical wargaming articles Oriskany – and, of course, your not so secret secret weapon, sorry sauce: key scenes using models, the strategic and tactical maps, as well as the historical photos – combined with the detailed annotations. Excellent work! You’ve almost certainly already read John Keegan’s “Battle At Sea” which Includes Midway. For those of you who haven’t read it, this book gives a good Introduction to key naval battles, such as Midway, Trafalgar and Jutland. To be honest, I bought Battle At Sea as I am interested in Jutland – my Grandfather was an officer on… Read more »

Thanks, @aztecjaguar – Actually, sorry to say I don’t have that one. I know, right? John Keegan? In my defense, the man wrote quite a bit. To own a copy of it all you’d almost need an addition on your house. 😀 I was mentioning Jutland the other day on the Hobby Night Live thread. I built a fleet of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers for Fire When Ready, 60 ships in all – well, 60 playing pieces, not sure I would call my ships miniatures – they’re certainly nothing like Q@ecclesiastes ‘ miniatures. Anyway, looks pretty sweet all set up… Read more »

I know they would be huge but I want a 1:200 US and Japanese carriers so that I can display my Wings of Glory Aircraft.

Thanks, @turbocooler . Eh . . . they wouldn’t be too big (cough, cough) at 1:200. A fleet carrier’s flight deck of the day would be four feet long. Great, eh? Even at 1:200 a single “unit” is bigger than many gaming tables. 😀

great work @oriskany @ecclesiastes on the article and models will definitely see the battle in a different light.

Thanks, @zorg . Glad you liked the article and hope you like Part 03. 😀

cant wait.

Cool deal. Those dive-bombers mentioned at the end of this article really kick things off in Part 03. 😀

a free run with no fighters definitely makes it easier.

Part 03 MIGHT be slightly delayed in publication – site issues. 😀 We’ll see what happens and hope for the best!

Do I sniff a sense of pride in the author about the American Attitude this battle was fought in and the American Navy in total (then and today) ? 😀 Don’t get me wrong, there is nothing wrong with “being proud” or at least there should be nothing wrong with it. We Germans just have a very complicated relationship with being proud of military achievements. And Midway is definately one of hell of a military achievement. So I actually envy you to be able to “feel proud” without remorse whether this is “right” or “politically correct”. Great article again. Did… Read more »

@bothi, I get a lot of the complicated relationship you are talking about from my German friends here in Australia. The answer is that you are not guilty of the sins of the father, so speak your mind without guilt. Unless of coarse you start talking about playground domination and the extermination of all hamsters as a final solution. Then it becomes a whole new problem. Around the post war generations you can speak with pride of German achievements, there is a lot to talk about. Just be sensitive around the generation that did the actual fighting.

My family originally comes from Montana in the American northwest, where at least 20 major battles against Native American tribes took place in the 1860s, 70s, and 80s. Included among these is Little Bighorn, probably the most famous (and infamous) “Indian Battle” of all. Needless to say we have to be a little careful with our relationship with these wars and political, social, and cultural background against which they stand.

I tried to recall the first time I read a history of the war in the Pacific: I think it was around 44/45 years ago. You summation of events thus far around Midway and the ‘noises off stage’ are fabulous!

Great part 2 @oriskany. As it is 3am here I will talk more when I wake up, but by that time you will be asleep.

No worries, sir. Thanks for the comment and get a good night’s sleep! 😀

Great article and I’m really looking forward to part three, and those photo’s really set the mood, especially that last one

Indeed that last photo is beyond epic, @hairybrains . Full credit to @ecclesiates on that one, not only the photo but the IDEA for the photo and where it would go in the series.

The Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway are both observed out here and around their anniversaries documentaries are aired. At least one of them focused purely on the moment you are about to describe. However knowing exactly what is about to happen does not spoil the enjoyment of this article series. Oddly an insight to carrier warfare for me came from a documentary on the making of the 1960’s film of The Battle of Britain. They wanted shots of the bombers and fighter streams crossing the channel from France. They had tremendous issues in getting this shot. By the… Read more »

Thanks, @jamesevans140 – Such “management” mechanics are important in more complex carrier-themed games like Avalon Hill’s Flattop, where it’s important to know where you aircraft squadrons are, they’re furl status, whether they can make it back to your carriers before night falls … And when they’re on your carriers, whether they’re prepared on the flight deck or in the hangar being maintained / loaded, and with what ordinance. In a game specifically about carriers, that kind of detail is important. Not sure if we’d need it in a system like Naval War or War at Sea. 😀 At Midway, the… Read more »

@ecclesiastes I left a comment for you under part one as I did not want to clutter up part two with a conversation started in part one.

Sorry, almost meant to add that IO 100% agree with your mention of the strange dichotomies of Japanese naval doctrine and thought. Yes, they’d proven moreso than anyone else just how “dead” the battleship really was with Pearl Harbor, Renown and Repulse, etc. Yet they still believed in their OWN battleships somehow. At least many of them did. I’ve always been interested in Yamamoto’s quote: These battleships in our navy are like carrying a samurai sword in battle. They are more religious objects than military resources.” Given how much of Japanese culture (i.e., the Army) felt about Shinto religion and… Read more »

To be fair to the Japanese, all major powers clung to their battleships. Even Hitler wanted a high seas fleet and only switched to submarines after the surface navy had suffered several major defeats. And even after the war, several countries kept battleships in service for a decade or more. Heck, the US used several in the first Iraq war… 😮 Another strange dichotomy can be seen in the bombing campaign against Germany. The London Blitz failed entirely to break the will of the Brits to fight. Yet, for some reason, the Allies believed it would work against the Germans.… Read more »

To be fair to the Japanese, all major powers clung to their battleships. Well sure. What I find interesting is how some elements of the Japanese naval command structure continued to place battleships at the center of their planning, and others did not (i.e., Yamamoto, as quote above), all while Japanese naval operations repeatedly PROVED the battleship’s obsolescence through the first six months of the US-Japanese Pacific War. It’s almost like they were continually proving themselves to be more advanced than their own theories. Meanwhile, not all the Japanese naval commanders or planners clung to the battleship (e.g., Yamamoto as… Read more »

I believe you are right in what you say. Everyone normally begins fighting a new war as if it was like the last. Yet no two wars are the same. What does not stop is the politics and power broking especially when the dynamics and status quo are being upset. The actual winning of the war becomes secondary. This sounds like nonsense until you read the political histories of a given war. Take for example land warfare prior to the beginning of WW2. You have the centuries old cavalry as the prestige arm. It’s officers have most of the top… Read more »

@oriskany completely agree. The US at this stage still were learning this new carrier based war thing. They were having trouble coordinating their bomber types within an effective fighter screen. Compared with their strikes in the latter part of the war, this looks like a drunken effort. This is not to say they were incompetent as experience and lessons learned have not had enough time to have an effect. The same as the German blitzkrieg. In Poland it was effective but not quite there yet. By the time their get to Barbarossa blitzkrieg is looking like a well oiled machine.… Read more »

While I would agree that many nations, America included, were still learning the trade of carrier warfare, I would maintain that the Americans of TF 16 and 17 were a little better than the morning of June 4, 1942 would have us believe. Note, I say a little better. 😀 The Americans knew the Japanese fleet was out there, USMC and USAAF bombers based off Midway bad been trying to hit them throughout the previous day to no effect. Then the Japanese hit Midway on the morning of June 4, hard. So the Americans knew the Japanese were close (based… Read more »

History can be a difficult read at times, especially so given the doomed nature some of the men faced at Midway. Their courage leaps well beyond the boundaries of many today.

On a lighter note, I particularly like the last photo of the planes appearing over the clouds behind the Japanese carrier, very dramatic. Kudos to whoever arranged that picture.

@redvers, I totally agree that photo is my favorite gaming photo to date.

All @ecclesiates on that one, @redvers and jamesevans140. 😀 We were talking about photos, what miniatures he had, what parts of the battles we wanted to cover, and how the battle’s events would be spaced out over the parts of the article series. His idea for a “cliffhanger” photo of the SBD Dauntless dive bombers arriving “out of the sun” over the Japanese flagship Akagi sounded great as soon as he mentioned it. 😀

Sorry @oriskany for the time that it had taken to reply to your comments. I wrote a reply yesterday. I then went and had a meal then I came back and finished it off. When I submitted it requested me too log on again and once I had my submition was lost. I did not feel like rewriting again. Well between your efforts and photography your photos between your efforts have come out great. You guys have taken the wargame article to a new level where the photos are now also telling some of the story. I agree with what… Read more »

No worries, @jamesevans140 – 😀 Just while we’re on the topic of carrier innovation, etc., we should really point out that while the Americans and Japanese probably built the first real “carrier fleets” and showed the world what these fleets are really capable of across thousands of miles of ocean, the BRITISH really should not be forgotten as the true innovators when it comes the carrier itself. First purpose-built aircraft carrier designed, of course – HMS Hermes 1924 (although I think Hosho was actually completed first) First full-length flight deck (i.e., the “model” aircraft carrier) – HMS Argus First pilot… Read more »

The Secretary was actually the approaching aircraft and it was her mirror, however her contribution to history is all but forgotten. The pre purpose built history of the carrier reads in a similar fashion. The innovation of landing lines and catch hooks, the development towards the classic flight deck arrangement. I don’t remember the exact details to this. Towards the end of WW1 the RNAS laugh an attack from one or two converted carriers against a Zeplin hanger. The Sopwith Pup features large in this attack. These details of this attack are usually featured in extended histories of this aircraft.… Read more »

Thanks, @jamesevans140 – I guess I didn’t know t he particulars of the story or even how those landing “guide beams” work exactly.

I found the name of the book I was thinking of while talking about the stratification of calcification of military thought …

War: by Gwynne Dyer

https://www.amazon.com/War-1985-soft-cover-Gwynne/dp/B0013V9SJY/ref=sr_1_12?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1496689899&sr=1-12

Oh, no. Not Gwynne Dyer! He is the most despised ‘pundit’ the Canadian military has ever known. I believe he reached the lofty rank of sub-lieutenant before being drummed out of the navy for being a self-absorbed, tactically inept sh#t pump.

He regularly lobbies to have defence budgets slashed as retaliation.

Wow, really? Didn’t know all that. I only read the one book, I know he’s written a lot more so I don’t really know about his general “posture” or politics or body of work. A lot of what I read in “War” seemed to make sense and wasn’t too judgmental – although I think he’s re-written it with “War – the Lethal Custom” which may change my mind.

OK, now that I’ve calmed down…

Much of what Dyer writes is a rehash of the work of others. Doesn’t mean its wrong; just means the analyses aren’t his.

He also wrote firsthand accounts of conflicts he wasn’t invited to.

Much of what Dyer writes is a rehash of the work of others

You know what they say. History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other. 😀

@cpauls1 I know where you are coming from. Another author that I will not name in his books he uses quotations, some out of context, to basically do a character assassination on someone he does not like. When challenged he claims only to be quoting from history. Yet somehow managed not to use opposing quotes for balance. He comes across like a little boy blowing raspberries while hiding behind mum’s skirt. Some would place Liddell Hart in this category for his perpetual quest for claiming blitzkrieg as his but others got the credit for it. While he can have some… Read more »