The Battle Of Midway 75th Anniversary: Turning Point In The Pacific [Part Four]

June 12, 2017 by oriskany

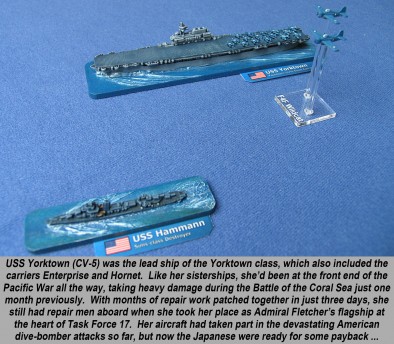

Good afternoon, Beasts of War, and welcome back to our article series commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Midway. Fought between the navies of the United States and Japan in 1942, few naval battles in the history of warfare have altered the course of a war so radically and so quickly.

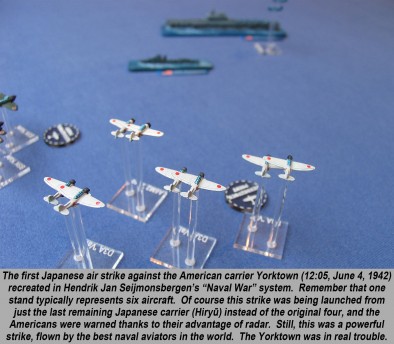

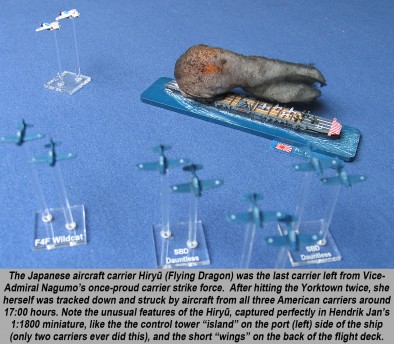

In taking this “wargamer’s tour” of Midway, I’ve had the great pleasure of working with Hendrik Jan Seijmonsbergen (BoW: @ecclesiastes), who’s provided dozens of fantastic photos of warship miniatures need to do Midway justice, and battle reports from Midway wargames, as played in his “Naval War” system available here: www.naval-war.com.

If you’re just joining us, so far we’ve reviewed Midway’s significance and Japanese planning in Part One. Part Two reviewed initial approaches and first strikes, and Part Three saw the tide of the battle (and the Pacific War) turn with a devastating American dive-bomber attack that crippled most of the Japanese carriers.

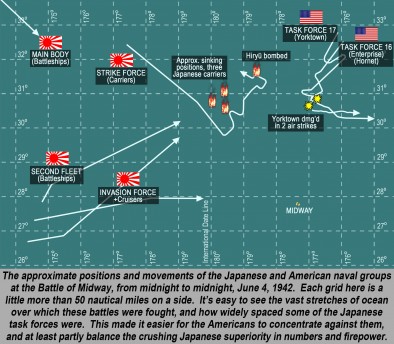

But even having suffered such a devastating blow (the loss of their carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Sōryu, along with hundreds of priceless naval pilots), the Japanese weren’t giving up. They still had one carrier left, the Hiryū (“Flying Dragon”), and were hell-bent on payback for what the Americans had done to them.

Vengeance

With the other three Japanese carriers still burning, the Hiryū was immediately given orders to launch every plane she had at the Americans. This was done quickly enough, as the Japanese fleet had been preparing to launch a strike anyway when those dive-bombers had arrived to wreak some unimaginable damage.

The Japanese air strike, naturally, was much smaller than originally planned. Still, the carrier Hiryū sent up a force of Aichi D3A dive-bombers (code-named “Val” by the Americans) and an escort force of Zero fighters. But here is where we run into the first big difference between American and Japanese carrier task forces …

The Americans had radar. The Japanese did not.

Bear in mind, “radar” in the early 1940s was hardly what it is today. Nevertheless, the American carrier Yorktown was able to detect the incoming Japanese strike about seventy-five miles out (roughly eighteen minutes’ warning).

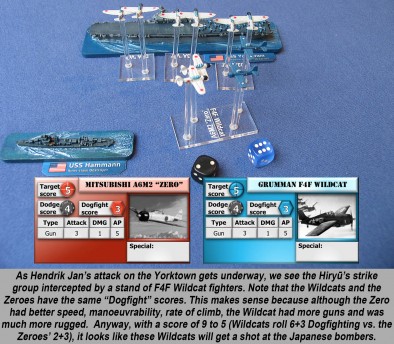

Thus, the dozen or so F4F Wildcat fighters already flying CAP (“Combat Air Patrol”) were able to intercept the Japanese well before they reached the Yorktown. This interception gave the Yorktown time to launch fifteen more Wildcats, ensuring the Japanese “Val” dive-bombers would have a hell of a time making the bombing run.

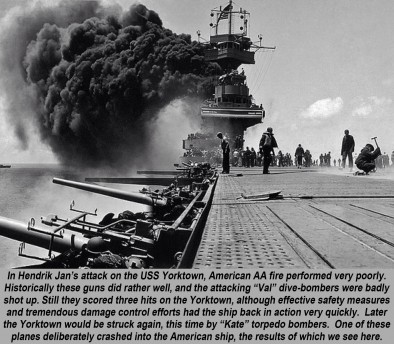

Nevertheless, the escorting Zero fighters managed to tangle up the Wildcats enough for fourteen Vals to get through. Nine more were lost to AA fire, but five survived to drop bombs, three of them hitting the USS Yorktown. But here is where we see another difference between Japanese and American warships: Damage control.

Where three hits, two, or even one bomb hit had blown up Japanese carriers like 38,000-ton boxes of gasoline-soaked fireworks, Yorktown was able to survive similar bomb hits with remarkable resilience. Mostly the reasons boil down to better training in damage control and that crucial few minutes’ warning afforded by radar.

One, there was no ordinance left stacked on Yorktown’s flight or hangar decks. American carrier crews were also trained to flood their aircraft fuelling lines with carbon-dioxide during an attack, ensuring that high-octane aviation fuel would not blow up if these fuel lines took a hit. Fire fighting training and equipment was also much better.

Nevertheless, Yorktown was badly damaged, losing almost all her boilers, two of her three aircraft lifts (enormous elevators in the flight deck that bring up aircraft from the hangar deck below) and her radar room. But fires were quickly brought under control, and no fuel or magazines exploded within Yorktown’s hull.

So complete and so fast was Yorktown’s recovery, in fact, that less than two hours after being hit, she was making twenty knots under her own power and even launching and recovering her own fighters.

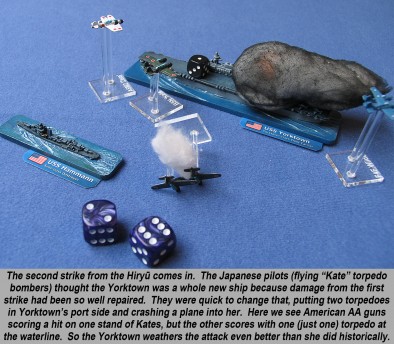

It was a good thing Yorktown had those fighters in the air because the defiant Hiryū (again, the last Japanese carrier at Midway) had already launched her last aircraft, a cobbled-together group of Zero fighters and Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bombers. Their target, again, was the Yorktown.

This second Japanese attack wave was mostly drawn from the squadrons of the dying carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Sōryu, planes that had been fortunate enough to be in the air when the Dauntless dive-bombers had gutted the three Japanese carriers. Such was the state of the once-proud Japanese carrier air force at Midway.

Again forewarned, the Yorktown’s fighters were able to make the Japanese pay dearly for this second strike. Since the Yorktown was not burning and making good speed, the Japanese, in fact, thought they were attacking either the Enterprise or Hornet (remember these ships were all of the Yorktown class, and thus look almost exactly alike).

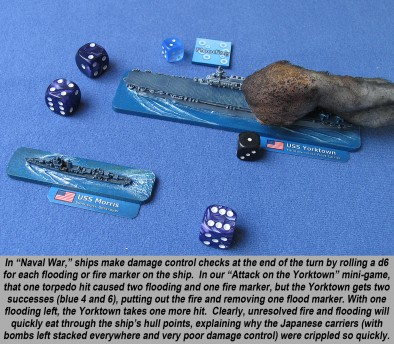

Despite horrific losses, five Kates managed to launch torpedoes into the water against Yorktown, two of which hit her on the port (left) side. One of the Kates also deliberately crashed directly into the Yorktown, setting off a titanic explosion.

This time Admiral Fletcher had to give the order to abandon ship. Still, the Yorktown wouldn’t sink, and throughout the afternoon and evening, firefighting efforts continued, as well as counterflooding to correct the ship’s dangerous list to port. For a while it looked like the Yorktown might yet be towed back to Pearl Harbor and saved …

Hiryu's Last Stand

Even as the Yorktown fought for her life, her scout planes had re-located the last Japanese carrier, the Hiryū. The two carriers from Task Force 17 (USS Enterprise and Hornet) launched a combined strike at the Hiryū, including some aircraft “orphaned” from the crippled Yorktown.

By 1700 hours on June 4th, this massed force of SBD “Dauntless” dive-bombers and Wildcat fighters had reached the Hiryū and were screaming down out of the sky. Hiryū twisted and turned, every gun ablaze, her remaining Zero fighters fighting back frantically.

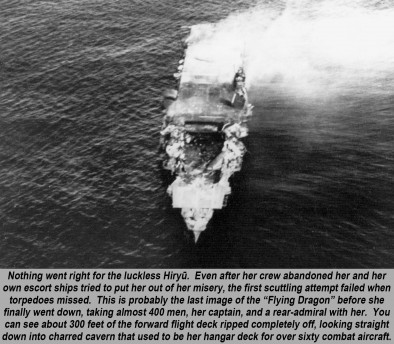

None of it helped. Despite valiant Japanese efforts, the Hiryū was struck by no less than four bombs. The first two hit near the bow, blowing the massive forward elevator completely from its housing. The other two struck aft, again catching a waiting strike wing as it was poised for take-off. Ammunition and fuel exploded, and Hiryū was doomed.

It’s genuinely difficult to overstate the dramatic cataclysm that had befallen the Japanese through the course of June 4th, 1942. In just one day, the dominant power of their “Kidō Butai” carrier strike force had been broken forever. Even worse than the loss of the carriers were the aircraft, and the priceless experience of hundreds of elite pilots.

Yet even now, the Battle of Midway was not over. As the sun finally set on June 4th, 1942, and the smouldering hulks of the Akagi, Kaga, Sōryu, and Hiryū entered their final death throes, the American carrier USS Yorktown was still fighting for her life. Fires and flooding were again under control … could the ship still be saved?

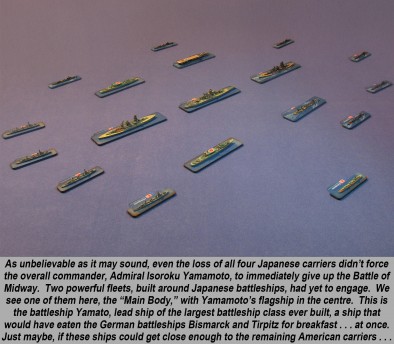

Also, hundreds of miles to the west, huge fleets of powerful Japanese battleships and cruisers had yet to engage. Among these was the flagship of the Japanese Navy, the battleship Yamato, the largest battleship the world would ever see. There was also the Midway Invasion Force, with yet more battleships, cruisers, and 5000 Japanese marines.

Even now, was it remotely possible that these dreadnaughts could catch the American carriers in a gunnery duel? Could the slaughter of the Japanese carrier strike group be revisited upon the Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown (assuming she was still afloat when the sun came up), using the “big battlewagon guns” instead of aircraft?

We hope you’ve enjoyed this wargamer’s look at the Battle of Midway. The battle is just about over at this point, but a few last strikes remain. In next week’s finale, we’ll look why Midway turned out this way, review the battle’s effects (both in the Pacific War and naval warfare in general), and perhaps some “what-if” alternative outcomes.

Most importantly, we’ll look at how battles like Midway can best be adopted into a wargame setting. Miniatures rules can be a little problematic, after all, when your battle area is 500 miles across, some of your combat units move at 300 miles per hour, and other units are 800+ feet long.

Meanwhile, we hope you’ll check out Hendrik Jan Seijmonsbergen’s “Naval War” system at www.naval-war.com, quite honestly one of the best-rounded, most applicable systems (not too detailed, not too simple) I’ve seen for WWII naval combat. And of course, comment below, and come back next week for the grand finale!

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"They still had one carrier left, the Hiryū (“Flying Dragon”), and were hell-bent on payback for what the Americans had done to them..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"...we hope you’ll check out Hendrik Jan Seijmonsbergen’s “Naval War” system at www.naval-war.com"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Wow! Great pictures I’ve never seen that one of the wrecked Hiryu before. Looking forward to the last part.

Awesome, thanks very much, @gremlin ! 😀 Yeah, there aren’t that many photos of many of the Japanese ships at Midway. As far as internet searches go, it’s also tough to find photos that aren’t altered too much or are of high resolution quality.

As far as the American warships involved, there are almost too many. And paintings too. I swear, if I run across just one more rendition of McClusky’s SBD Dauntlesses bombing the Akagi . . . 🙂

The last part wraps up the battle, discusses some “reasons why” and “what-ifs”, and kicks around some gaming options (or factors a Midway game should have in it, no matter what system is used, both tactically and operationally)

The one thing that still puzzles me is that so many Japanese crews, including high-ranking officers, willingly choose to go down with their ships. I know it is Bushido and such, but still can there be a bigger waste of battle experience than to just let your crack crews commit suicide while they could be saved and use their experience to train and command other ships? I still cannot comprehend why the Japanese command did not think it was prudent to find a way around this…

I also think that this was a major part in the abysmal damage control abilities that the Japanese show throughout the war.

Couldn’t agree more, @ecclesiastes . While the story of Rear-Admiral Yamaguchi and Captain Kaku standing on the bridge as Hiryu went down, remarking on the beauty of the moon (“How bright it shines” … “it must be in its 21st day”) is a nice one, you can’t help but notice it’s also costing the Japanese Navy 50+ years of officer experience.

This in a battle that has already cost the Japanese centuries of top naval aviator experience. That one bomb strike on the fantail of the Akagi is estimated to have killed 300 years worth of pilot training (sixty elite pilots, all with at least five years of training and combat flying hours). Multiply this by four carriers! You have over a millennium of priceless experience that just doesn’t get replaced. I mean it’s one thing to train a conscript rifleman and push a Mosin-Nagant into his hand, you can’t do that with aircraft carrier pilots.

Well, you can try. The Battle of the Philippine Sea is the result (June 1944) – the Americans call it the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. Ace pilots were landing on American carriers with up to SIX kills in a single sortie (more than 95% of fighter pilots get in a lifetime). Soon after it was kamikazes . . .

I also full agree about damage control (how can I not)? facts are facts and it’s in the article. 😀

A good example can be taken by the damage sustained by Yorktown vs, some of the Japanese carriers. One of them was crippled with just one, possibly two bomb hits (sources differ). Meanwhile, Yorktown was hit by three bombs, then two torpedoes, then an aircraft collision, and still she was going to make it until (spoilers) – you have to see what happens in Part 05! 😀

I already know what is in part 05 :D:D

To the subject, the point of damage control is that you learn by doing. If you let your whole damage control crew go down with the ship, there is no curve, the next crew will just make the same mistakes again….

I think Lexington and Shokaku illustrate this: Lexington went down, but most of her crew got of and US damage control improved accordingly with lessons learned. Shokaku is one of the few Japanese carriers that had time for a learning curve, since she survived Coral Sea, Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz. At Santa Cruz, she took quite a beating but didnt go down as her fuel lines were drained and her remaining aircraft launched. Her earlier experiences may have helped her there. Taiho and Shinano imho suffered from the lack of transferrable damage control experience. For Taiho specifically it is noted

“Meanwhile, leaking aviation gasoline accumulating in the forward elevator pit began vaporising and soon permeated the upper and lower hangar decks. The danger this posed to the ship was readily apparent to the damage control crews but, whether through inadequate training, lack of practice (only three months had passed since the ship’s commissioning) or general incompetence, their response to it proved fatally ineffectual. Efforts to pump out the damaged elevator well were bungled and no one thought to try to cover the increasingly lethal mixture with foam from the hangar’s fire suppression system.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_aircraft_carrier_Taih%C5%8D#Fate)

Seems they could have used some of the guys that went down with the other carriers to point some stuff out there….

Thanks, @ecclesiastes – If memory serves, and I mean that literally, I don’t have my books with me here at work 😀 . . . Shinano was also sailing with a partial crew? Part of a shakedown cruise or some such? So when she was torpedoed there wasn’t a full crew to enact damage control procedures / watertight compartments, etc.

I did read that the after Midway, the Japanese did try to establish some better damage control procedures, training, and equipment (speaking to what you’ve said about Shokaku).

I honestly don’t know very much about Taiho, other than the “high level” obvious (Ozawa, Philippine Sea, June 44, “Great Pheonix,” etc). I know she was pretty advanced ship, and the Japanese were hoping she’d form the nucleus of a revived Japanese carrier fleet. But of course, you can have all the carriers and even carrier aircraft you want, if your pilot corps has degraded too much in training and experience … 🙁

All for the honor – a waste – but they did not loose face

Morale and fighting spirit is a tricky thing. It is definitely important, and leading by example IS very important. But it can totally be overdone.

I’ve been thoroughly enjoying this thread and to have it pop up in time for my lunch, brilliant.

Thanks very much @brucelea ! Yeah, I think the team aims for mid-day publication on these articles for best initial reception. 😀 Glad you like the articles so far! One more to go!

Again, I am surprised at how anxious I am about how this will all turn out. Silly, I know, but the writing really keeps me on the edge of my seat even though I know the end of the movie 🙂

Hey, thanks very much @gladesrunner . 😀 Glad you liked it.

Thanks for this – a great read. It has opened my eyes to using miniatures for this sort of wargame… before I would have just used hex sheets and tokens. This has even encouraged me to reach out to some of my old Flat Top team to see what they are up to and if they still wargame (it has been a few years, probably over 30 – I suspect a number of partners might not be pleased).

Thanks, @itchardpirate . Hey, there’s nothing wrong with hex grids and counters, especially with a game like Flat Top. 😀 Still, great miniatures add a much more visceral and visual feel for the tactical aspect. For the overall operational picture, the movements and dispositions between battles, that requires some kind of tracking map. A hex grid, or even a longitude-latitude grid if you feel like getting out a protractor and plotting fleet movements like an actual staff officer! 😀

Another fascinating article from Oriskany – and this episode highlighted two aspects

of war that I had not really ever considered before:

– the importance of identifying worst case scenarios and then training for to mitigate

the effects of them (damage control)

– the valuable but difficult to quickly replace training and experience of commanding

officers and veteran pilots

How often are these aspects of a warfare represented in a tabletop game, I wonder?

Rather like politics, logistics, espionage, etc. almost certainly much too abstract or strategically “high level” for an isolated battle or skirmish game, especially at 28mm

or 15mm scale.

Perhaps this would make for an interesting article series: how thinking creatively (and questioning the wisdom of what had been done before) helped win wars.

Thanks, @aztecjaguar . Great points and great questions.

This statement is intended only in the broadest, most summary of terms, but the Japanese military in World War 2 seemed to be “hyperaggresive” in many of its doctrines and design. The Zero fighter was given very fast speed, nimble maneuverability, long range, and immense firepower up to and including 20mm cannon in some variants. But armor plating for the pilot? A self-sealing fuel tank?

Just one anecdotal example, but you see my point. Carriers were built to carry as many aircraft and as much ordinance as possible, but never really put much through into safety measures. Crews were trained to turn strike groups around as fast as possible, not so much in damage control.

Even what few safety procedures existed happened to be ignored on the Japanese carriers on the fateful morning on June 4 (as ordinance was switched back and forth on the Japanese strikes groups being prepared, the previous ordinance wasn’t taken back to magazine decks below the hangar decks).

Although the Japanese aren’t alone in this. Shortcuts in ammo handling is though to have caused some of the catastrophic explosions that claimed several British battlecruisers during the Battle of Jutland, 1916.

As far as training experienced officers and pilots, here the Americans (and I think the British as well) had a very different policy from many of their enemies. Once a pilot had seen a certain amount of experience, he was pulled OUT of combat. This is why the highest-scoring American ace (Maj. Richard Bong) – scored 40 kills while top German ace (Erich Hartmann) scored 352. German and Japanese pilots flew until they died. American (and I think British) pilots were pulled off combat flights and sent to train more pilots.

In this way, no matter how bad fighter losses may or may not have been, the Americans always had a “next rank” of solid pilots ready to step up and keep the squadrons operational.

How can things like this be represented on the table top?

Besides just assuming certain things are “for granted,” (there will always be more Shermans than Tigers, but Tiger crews will always be better trained and more experienced than Sherman crews, etc) . . . multilevel gaming seems the answer. Operational and strategic decisions and countermeasures can play out in a campaign setting, and when units meet for combat, a tabletop game is set up BASED ON THE CONDITIONS and force levels stipulated by what’s happening on the operational / strategic map.

Thanks for the comment!

Thank you Oriskany for your excellent reply to my post – I feel honoured to receive my very own Oriskany article!

You also anticipated my thoughts on other operational mistakes similar to the Japanese Imperial Navy’s limited damage control when their carriers were attacked and damaged:

and that would of course being the (probably avoidable) Battle Cruiser losses at the Battle of Jutland in 1916.

Here the problem, apparently, was the agressive “keep the big guns firing” orders to the 15″ gun crews on the British Battle Cruisers. This led to the safety procedures (to avoid “Flashbacks” igniting the magazines of cordite) being temporarily ignored in the heat of battle. The sealed and armoured “Flash doors” separating the levels within the gun turrets were fatally wedged open – to enable the shells and bags of cordite to be delivered as fast as possible up from the magazines located deep within the ships armoured “belt” to the big guns. This allowed an explosion or fire “up top” to have a rapid chain reaction of explosions reaching down into the huge quantities of cordite and the Hugh high explosive 15″ shells stored in the magazines, blowing the ships apart from within.

David Beatty, Commander of the Britsh battlecruiser Fleet, famously remarked: “There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today”, after two of his ships – including Battle Cruisers Invincible and Queen Mary exploded.

Finally, rather than accept the (correct) findings of the Investigation into the cause of what when “wrong” with the Battle cruisers at Jutland, First Sea Lord Jelicoe decided, against the evidence, that the problem was insufficient armour-plating. Perhaps it was a misplaced sense of loyality to the Naval officers, protecting them from being blamed for bad ammunition handling proceedures.

Looking forward to the final part of the Midway series and continuing to read all the comments from Orsikany and the Beastsofwar community.

@aztecjaguar – No worries, sir, and great post!

I’m a little less solid on World War I naval history and operations than I am on World War II, but I know the basics (Jutland, Dogger Bank, Heligoland Bank, the U-Boats, the first British aircraft carriers and the first aircraft carrier strikes against German zeppelin bases, etc).

You have probably already seen this documentary, but I found it very interesting and informative on the investigations done as to why those British battlecruiser blew up, both investigations at the time, and investigations carried out much more recently with deep sea submersibles on the wreck sites.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nCGOE6UiAWo

There are definitely some parallels between the improper procedures employed on the Japanese carriers on June 4 1942, and the British battlecruisers on May 31 1916. It’s a rough analogy, but if we think of aircraft as the carrier’s weapons, and the rate at which they can turn around squadrons and prepare new strikes as almost analogous to the rate of fire of the British 15″ guns, it’s basically the same. we want to throw weapons at the enemy at double the rate of speed, so let’s cut in half our safety procedures (already dangerously slim on Japanese carriers at the time).

Great post! Thanks very much!

Great read yet again – I did not have time to read it this morning , but I have caught up now

Thanks very much, @rasmus ! 😀 The site in general seems a little quiet today re: comments. Here’s hoping for more tomorrow (across all the topics, not just this one). 😀

“Post-UKgamesExpo Pre-Origins-GenCon” fatigue I guess. Heading off Wednesday myself

Thanks @rasmus . Heading off Thursday myself, a brief trip up to Canada. 😀

Thanks,

Great reading did the japs have radar technology then ?

Cheers Tim

@timp764 – actually no, the Japanese Navy was not equipped with radar at the time. In fact, radar was one of the facors that really helped determine how well USS Yorktown would weather the assaults thrown at her, she always had about 75 miles of warning when a Japanese strike was coming in, and so her fighter protection was always able to take the first big slice out of the incoming Japanese strike.

It’s hard to imagine a strike like McClusky’s SBD Dauntless dive-bombers being so insanely successful if the Japanese had radar on those four Japanese carriers or their escort ships.

But you can kind of tell the Japanese at the time weren’t even thinking in terms of radar. Yes, they knew about it, they knew the Americans had it . . . they just didn’t feel it was “necessary” or realize the magnitude to its advantage. Look at how they hoped a Japanese surface battleships fleet just might be able to sneak close enough to the American carriers in the dark and surprise them on the morning of June 5 or 6. Radar can see in the dark, guys. The Americans might not be able to launch a strike at you until morning, but they will know you are there and have a fully-loaded airstrike on all their carrier decks ready to launch at first light.

a great read I think the emotions were to strong with the Japanese pilots out for revenge the radar was the final straw for the last runs. another thing that affected future pilots was the best pilots never returned to the flight schools to pass on the skills learned in combat. @oriskany

Thanks, @zorg . 😀 Indeed, after so much time in combat (I forget what the exact criteria was, it might have been number of combat missions), American pilots were often rotated back to work as instructors. So say you have a thousand pilots, and in the German or Japanese model, you have three pilots that are gods at 100%, but then the other 997 drop off rapidly, until 500 or so are below 10%. The Americans, on the other hand, have a full 1000 (or more), all at 80%.

Who’s winning that fight?

To be fair, both the German and Japanese pilot training programs also suffered more and more as the war progressed from a crippling lack of fuel. You can’t train if you can’t fly, and you can’t fly if you barely have enough fuel to put combat-rated pilots in the air in desperate, outnumbered defensive battles as it is.

yes but some of the best German pilots were trained with gliders which would have helped with most of the basic training on the fuel front. @oriskany

@zorg – Earlier in the war, sure. Before Hitler basically shut down the German airborne program after Crete. I don’t think German airborne operations were ever undertaken again. @piers would know for sure on that one.

probably not.

😀

You take Bushido and twist it, then force feed it to a population twisting society. A twisted society can only have twisted views. Such as damage control is beneath a warrior even though you in a brining ship at sea.

Radar like the aircraft carrier was having a difficult birth. Yet battle space intelligence was fully appreciated at the time and much effort was placed in gaining it. Scout plans, submarines, fast light cruisers, light cavalry and armored cars were all purpose built to this endeavour. Yet even in the militaries that used it, it was not unilaterally excepted.

Perhaps it felt too much like witchcraft at the time. Was it perceived as a threat to the rule of the traditional intelligence gatherers? For Japan it could be one of those logical back flips. Such as accept the aircraft carrier but seek a dreadnaught solution.

One thing is that in WW2 the world in those short years had never seen such turmoil, strife, social upheaval and technological change. Sitting in the eye of this storm it would have been extremely difficult to see, let alone choose the correct path. Experimentation at every level of our existence is happening. So I suppose for the young its was a time of excitement, even greater than today’s youth. For those that were older they could only hold onto the only solid ground they could find. Tradition.

Thanks, @jamesevans140 –

The Japanese doctrine and military philosophies in World War 2 are a mystery to me. On one hand they embraced new technology, in other areas they shunned it. Is many ways they led the world in new tactics and doctrine, in others they were throwbacks. And it’s not even a Japanese Army vs. Navy thing, because both had plenty of merits and flaws in these regards.

Yamamoto wrote before the war: “Battleships are like religious scrolls old people hang up in their houses. They are a matter of faith, not fact.” So to a large extent the Japanese Navy was leading the world in large-scale carrier operations, demonstrated with thunderbolt clarity at Pearl Harbor. Later they would lose many of their carriers, and so fell back on the battleship as a second position. But I think deep down, most knew the carrier was the way forward. They started converting old battleships into “hybrid” carriers, and straight-out converted the third Yamato-class battleship Shinano into a carrier mid-way through construction.

Then you have the Army, who supposed never built a more technologically-advanced, well-equipped army because “Japan was a maritime nation, and never envisioned large land wars.” Huh? They invaded CHINA, you don’t get into larger land wars than that. And yes, China’s army at the time was hardly a world-beater, but they Japanese also suffered two harsh defeats at the hands of the Soviets in 1938 and 39. THAT didn’t set off alarm bells?

So I dunno. They “shunned” radar, but had the world’s most advanced torpedoes and were the world’s absolute best at night naval tactics (when radar is the most useful). The prized and venerated their aces, but sent them up in flying death machines. Don’t get me wrong, any nation’s military is going to have some contradictions, but the Imperial Japanese Navy of of World War II is just a fascinating puzzle for me.

The IJN vs IJA rivalry would have contributed quite a lot to the RADAR issue, since it wasn’t tech that could have immediate proof of value that the two groups could show off, there’s also the whole them not cooperating with their research teams. I don’t think they “shunned” radar so much as they didn’t have any good radar tech throughout the war and so figured they couldn’t rely on it anyway.

On the aircraft issue, Japanese pilots experiences during the fighting in Manchuko and China against the highly maneuverable soviet biplanes led them to prize maneuverability over anything else. And since the Japanese aircraft engines weren’t as powerful as the US, UK or German ones, when the IJN wanted a new fighter with speed, firepower and range as well as the high maneuverability demanded by its pilots, it was the armour that had to go.

As for the Army, in regards to their never large land wars, well they did intend for that war to be a short lighting war with a quick Chinese surrender, the fact that the Chinese didn’t surrender quickly was a big shock to the Japanese. But more than that, a modern army is expensive in resources, motorizing the army when they where facing massive oil shortages simply wasn’t an option, and tanks and artillery need a lot of metals which again, they had shortages in, especially since the IJN needed so much of that for its ships. I mean the Japanese where reluctant to even experiment given their resource shortages.

Great comment, @denythewitch .

The IJN vs IJA rivalry would have contributed quite a lot to the RADAR issue, since it wasn’t tech that could have immediate proof of value that the two groups could show off

That’s actually a great point. Technology like radar was seen (at the time) in many circles as a “defensive” measure, and since you win wars by ATTACKING people, the militaries of some of the more aggressive nations didn’t immediately see the full applications. The Germans are a good example of this in early WW2. They had radar, they knew how it worked technically, but didn’t operationalize it right away into a full air defense network like the British did during the Battle of Britain. They couldn’t understand where the RAF was getting so many fighters and pilots, not fully realizing that radar was allowing the RAF to vector interceptors only exactly where and when they were needed.

Of course, once the RAF and USAAF started bombing German cities . . .

. . .when the IJN wanted a new fighter with speed, firepower and range as well as the high maneuverability demanded by its pilots, it was the armour that had to go.

Indeed. Again, I think this is another symptom of the same basic “flaw” in some of the thinking. In any military doctrine or technology, mobility and lethality are two of the primary concerns. But a third is survivability. War is a “contact sport,” as they say. 😀 And while I understand where the Japanese were coming from with their “best defense is a good offense” – “the enemy can’t kill you if you kill him first” methodology, in a war where the enemy is at least at technologically or industrially as advanced as you are, he’s gonna land some hits now and then and your guys have to be able to “take it on the chin.”

To be fair to the Japanese, they’re certainly not the only ones to fall into this. The British certainly did in WW1-WW2 with the whole “battlecruiser” concept. “Speed isn’t replacing armor, speed IS armor” as Jackie Fischer said (paraphrasing there). Of course Jutland and Denmark Strait show otherwise. I don’t care if your battlecruiser raises steam to 32 knots instead of 28 knots, she’s not outrunning a German 15” shell.

We’re even running into this a little with our Arab-Israeli Wars content. The IDF had won so many battles and wars with its “hit hard, hit first” doctrine . . . focusing on tanks, strike aircraft, and elite light infantry (“paratroopers” in halftracks) – that when they finally WERE put on the defensive in Yom Kippur they found they were lacking a little in bedrock defensive assets like infantry, engineers, and especially artillery.

Great point about the resources in metals and oils needed for development and large-scale industrialization / mobilization of and tanks and artillery. These were shortfalls that really helped start the war with the US / UK / Australia / Netherlands / France in the first place, and certainly would have slowed any attempt to expand on these kinds of assets and units.

Thanks

It’s been a great series can’t wait for next weeks episode

Cheers

Tim

Thanks very much, @timp764 ! 😀 One more to go!

Great article as always @oriskany .

It just puts more emphasis on how wars are won: Information, information, information.

You know that you’re enemy is planning a trap and where? Let’s turn it around.

You know when the enemy planes are coming? Intercept them.

You know where the enemy u-boats are (enigma)? Well send the convoys around.

You know the tactics of your enemy (El Alamein)? Let’s fight where those tactics won’t work.

Things like these always have a big impression on me. Two seemingly small differences (Radar and breaking the Japanese Codes) made all the difference in the Battle of Midway. Ok maybe not all the difference, but I think the deciding ones. Imagine what would / could have happened when you strike those two factors out of the equation.

##SPOILER AHEAD## (I still don’t know if you really can spoiler history)

Similar impressive is how long the Yorktown managed to stay afloat. The damage control systems (not in the meaning of technical systems, but more in the likes of a paradigm) made it, that it nearly took the same amount of “pounding” to get rid of the Yorktown than the 4 Japanese Carriers in total. At least a similar amount than the three first carriers that sunk. And then again the Japanese Carriers went down in hours. The Yorktown fought on for about the same amount combined of the Japanese Carriers. Very impressive. I saw pictures from when they found the wreckage of the Yorktown in ’98. The damage doesn’t even seem that substantial. Maybe they could have saved her. If she just hadn’t been on beams-end.

But I’ve read that the torpedoes that hit her came from an Japanese Sub and not Kate Torpedo Bombers. And that a destroyer trying to stabilize her was sunk in the process. Is that wrong? Or do I just get ahead of myself / the article?

Thanks very much, @bothi ! 😀

It just puts more emphasis on how wars are won: Information, information, information.

Knowledge is power, as they say. 😀

In regards to radar and the broken Japanese naval codes, I would agree 100% that these are crucial factors, and that 90% of battles are won or lost before the first shot is fired. That’s doesn’t bode very well for “wargaming,” but it’s honestly true, and speaks to the idea that wargames can never really be completely accurate. Nor should they strive to be, or else they wouldn’t be fun.

And just because the outcome of a battle may be heavily influenced by these information-driven preconditions, doesn’t mean the battle is “over.” You could argue that ultimate outcome World War 2 in general was decided at the end of 1941, that doesn’t mean the fighting, cost, or sacrifice from 42-45 wasn’t “necessary.”

The Yorktown was indeed a heroic ship. She should hve sunk at Coral Sea, she should have spent three months (instead of three days) I drydock at Pearl Harbor before Midway. She could have sunk after the first air strike, she probably SHOULD have sunk after the second air strike. Yet still she might make it . . .

Unless you’ve ever read a history book on Midway. SPOILERS! 🙁 🙁

Yes, she totally survives the Kate torpedo bombers, and would have made it under tow back to Pearl Harbor … except for a Japanese submarine named I-168.

No worries, @bothi – you can’t really “spoil” history, especially when the name of the article series includes the phrase “75 Year Anniversary.” 😀

75 years? People have had a chance to see it in the theater AND the director’s cut. 😀

The whole Japanese aims, goals and technology thing is a complicated bowl of spaghetti or should I say noodles.

Another example comes from them watching the British.

They learned the lesson from Tarantino but completely ignored the radar lesson from the battle of Britain.

It is a really here take this medicine but don’t touch that it’s a witches brew.

Just to add onto @denythewitch comment. Again it’s that twisted Bushido thing again. To the warrior while his sword is his authority and instrument of justice. The speed of the sword is his shield and so a warrior needs no shield.

So the armour of the plane is linked to the word shield and becomes a dishonorable this to carry. In the original concept of the sword being the shield the samurai was expected to wear full body armour in battle.

However what @denythewitch is saying remains true, the sword is your shield is the fuel placed on that fire.

Thanks very much @jamesevans140 –

Hold on, the Japanese learned a lesson from Tarantino? Quentin Tarantino? Wow. Was this before or after he made Pulp Fiction 😀 😀 😀 Django Unchained? The Hateful Eight? 😀 😀

Just kidding, I know what you mean. HMS Illustrious making a strike on Taranto.

British influence on early IJN doctrine, tech, and shipbuilding is clear and unmistakable. Correct me if I’m wrong, but weren’t some of the ships or guns at 1905 Tsushima straight-out BOUGHT from the British?

I’m pretty sure the original Akagi battlecruiser and Kaga battleship designs were based on British influence.

And I should say Welcome to Beasts of War @timp764 !! 😀 😀