Home › Forums › Painting in Tabletop Gaming › What Are You Painting Now?

- This topic has 4,897 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 5 months ago by

brennon.

brennon.

-

AuthorPosts

-

January 3, 2020 at 11:57 am #1468169

Today’s all things 1938 A Very British Civil War is the first part of a three parter. Mainly because this covers a wide ranging faction, The Socialists and The Left Wing. The majority of this was originally written by Paul Cunningham. So lets go.

The Left Wing and the People’s Armies

Mosley’s elevation to PM came as a great shock to the left in Britain. The Battle of Cable Street in October 1936 had proved that when the left mobilised in force, Mosley’s Blackshirts could be stopped. But having the Blackshirts in government, with the resources of the British Empire at its disposal was an entirely different matter.

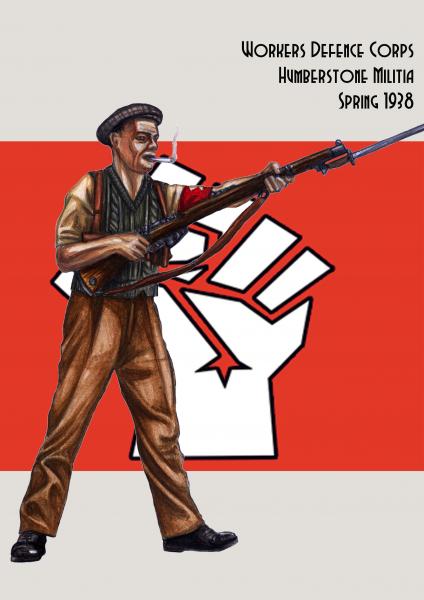

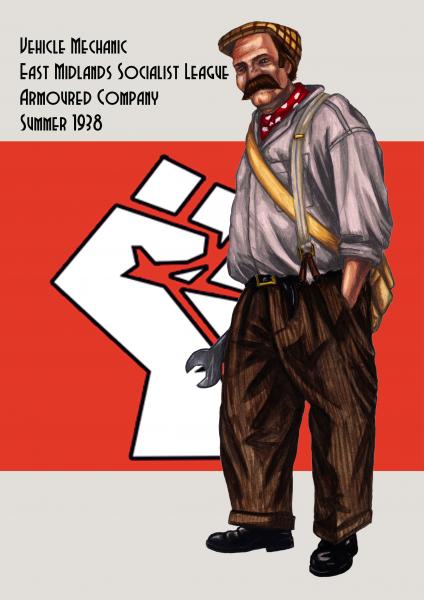

Workers Defence Corps

Growing out of the need to protect their marches and meetings from attack by gangs of Blackshirts, the Trade Union and Labour movement began to organize Defence Corps of workers. As the attacks worsened, weapons began to be used by both sides; fists gave way to clubs and knifes and the first serious casualties began to be sustained. After martial law was imposed in May 1938, shots were fired and armed British Union of Fascists militia began to attack Labour Clubs, Union offices and even Co-op stores. These were sacked and looted by black shirted mobs, who urged shoppers to boycott “Red-run shops”.The Workers Defence Corps were frequently organised by local Trades Councils, the local branch of the Trade Union Council. Lacking any uniforms other than a ubiquitous red brassard, tie or kerchief, these groups used whatever arms they could beg, borrow or steal. Their appearance closely followed that of working class men of the period; cloth caps or, for the skilled and office workers, trilby; trench coats, sports jackets or suits. In many cases, ties and collars, white mufflers or the local football team’s scarves were worn. Men’s clothes of the thirties used very few colours; brown, black, grey or navy blue, all in dark shades. Corduroy trousers in earth tones, with the occasional coloured woollen sweater, with or without sleeves, were sometimes seen. The use of military kit from WW1, acquired as souvenirs, was not unknown, although anyone affecting too military an appearance would have their legs pulled remorselessly; the exception being “tin hats” which were a much prized possession.

Some Workers Defence Corps were organised by trade union, location or occupational group. Pits or factories often had their own section, while the bigger plants could be at company strength. The very largest, Fords at Dagenham and the LNER militia, could be near battalion strength. Reflecting the views of the age, women tended not to be admitted to these units, but formed first aid teams, although there were exceptions. Some forceful individuals were integrated into mixed Workers Defence Corps, while some groups of female workers, mill girls in the cotton industry for example, formed their own defence corps. Although some Workers Defence Corps in the East End of London were composed overwhelmingly of Jewish members, the decision was made by the Trade Unions not to “divide the resistance” on ethnic or religious grounds.

Politically, the Workers Defence Corps wanted a return to an elected Parliament, the prosecution of Mosley and his supporters for crimes against the people and a raft of social welfare reforms. Not explicitly republican, the movement would be willing to fight alongside the pro-Duke of York faction, some Local Defence Volunteers and the Anglicans. Relations with the revolutionaries of the Independent Labour Party were strained, but cooperation was possible. Similarly with the Communists.As well as using their Trade Union banners, some groups often continued to wear their distinctive work clothes. Thus firemen, postmen, railway workers and busmen could be seen armed and taking the field in their uniforms. Miners often sported their helmets and lamps, while Dockers carried their infamous hooks as side arms. Since the Workers Defence Corps frequently elected their own “captains”, often union officials, rank marks were not needed. Gun shops were stripped of their stock, shot guns requisitioned and SMLEs “acquired” from Territorial Army, Regular Army or in ports, sympathetic Royal Navy mutineers. The occasional Lewis gun was present, but heavy weapons were absent. In time, successful clashes with the British Union of Fascists militias would yield Nazi-supplied arms as prizes. Improvised and experimental arms were also developed, including armoured vehicles made from commercial lorries and a range of exotic anti-tank weapons. Many of the Workers Defence Corps members were ex-servicemen, with Great War experience and therefore no stranger to the arms they acquired; transport was readily available in the form of requisitioned lorries, buses and charabancs.

In areas where the labour movement was strong before 1936, the Workers Defence Corps were capable of denying the streets to the British Union of Fascists and the forces of the crown. In some areas, the trades council set up Workers Councils that effectively ran affairs; South Yorkshire, the Fife coal field, Battersea, Hull, and Sheffield, etc.

In terms of military effectiveness, the Workers Defence Corps were varied. While they raise large numbers some sections were poorly armed, trained and led. Others proved dogged in defence of their neighbourhood and many of the new Council estates and large factories proved to be “no go” areas for anything less than British Union of Fascists legions or regular infantry. But even the most effective were prepared to travel only a very limited distance. They were thus incapable of acting as a strategic force against the forces of King Edward VIII and Prime Minister Mosley, partly due to this reluctance and partly due to their lack of heavy weapons.

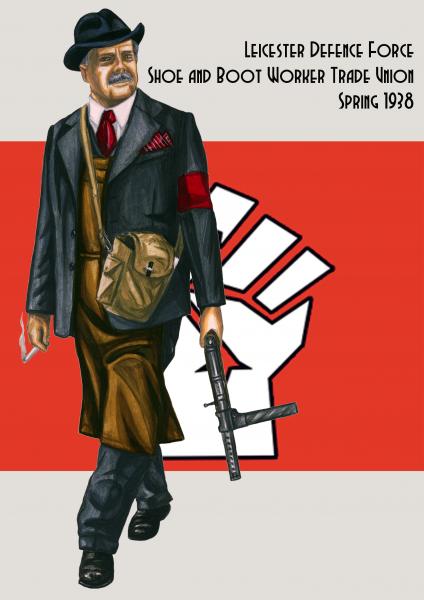

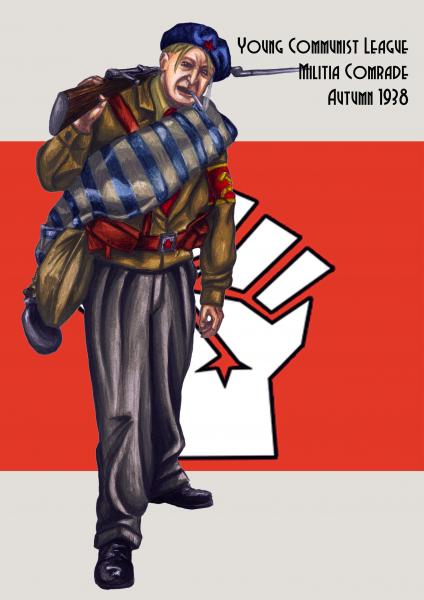

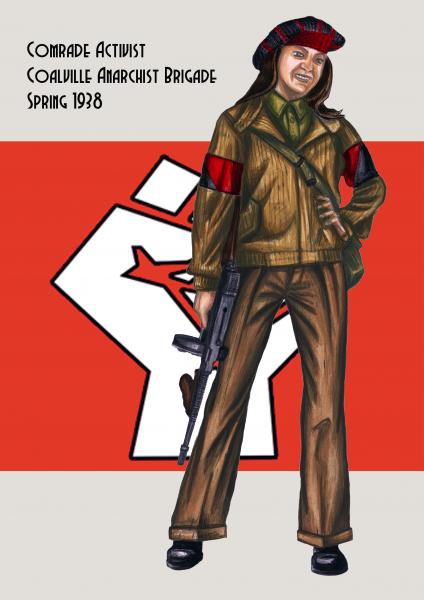

Independent Labour Party Militias or the “Worker’s Army”

The crisis drove the Independent Labour Party, which had disaffiliated from the mainstream Labour Party in 1932, sharply to the left. It adopted a policy of revolutionary socialism and saw the crisis as an opportunity to make the revolution. It wanted no compromises or cooperation with the “pro-capitalists” factions and urged the workers to take over the factories, docks and mills. From squads formed to fight the British Union of Fascists, armed groups of Independent Labour Party formed themselves into semi-autonomous militia units, sometimes ironically called the Worker’s Army by other factions; these groups invented stirring names for themselves, like “The Robert Kett Column”, “The Socialist Revolutionary Brigade” and so on.Based in Independent Labour Party strongholds including Glasgow, West Yorkshire and Norwich, these groups attracted those fighters radicalised by the crisis; anarchists, militant trade unionists and disillusioned ex-communists, some embittered by their experiences in the Spanish Civil War. The events in Spain and the role of the Communists in suppressing the Independent Labour Party’s’ sister party, the POUM, inevitably created deep hostility between the ILP and the Communists; this spilled over into conflict on more than one occasion.

The Worker’s Army groups attracted brave but militarily inexperienced younger members, with a sprinkling of ex-servicemen and ex-Spanish fighters. They attempted to dress as soldiers, wearing a variety of khaki army surplus clothing, including black or khaki berets and fore-and-aft caps like their comrades in the CNT/FAI militia in Spain. Some French surplus uniforms were smuggled in and worn by these militias. Red kerchiefs, overalls, breeches and puttees were also marks of this faction; traditional military smartness was disdained as “petty bourgeois” by these fighters and a studied scruffiness was the norm.

However, in the attack, none were as fearless or indifferent to casualties as these groups. Always poorly armed, with a range of rifles and few heavy weapons, they were led by their elected officers, always addressed as Comrade-Lieutenant, etc, who could be dismissed by their troops if incompetence or cowardice was suspected. They were organised into sections of 8-14 fighters, with the conventional platoon, company, battalion structure of the British Army of the period, although lacking in heavy weapons and armoured support. These troops integrated women into their ranks, as nurses but also as fighting soldiers, to the derision of the British Union of Fascists and the Communists. The smallest of the three main left-wing groups, the Independent Labour Party /Anarchists were very well motivated and brave to the point of foolishness, but poorly armed and difficult allies to their potential friends.

January 3, 2020 at 12:10 pm #1468171

January 3, 2020 at 12:10 pm #1468171

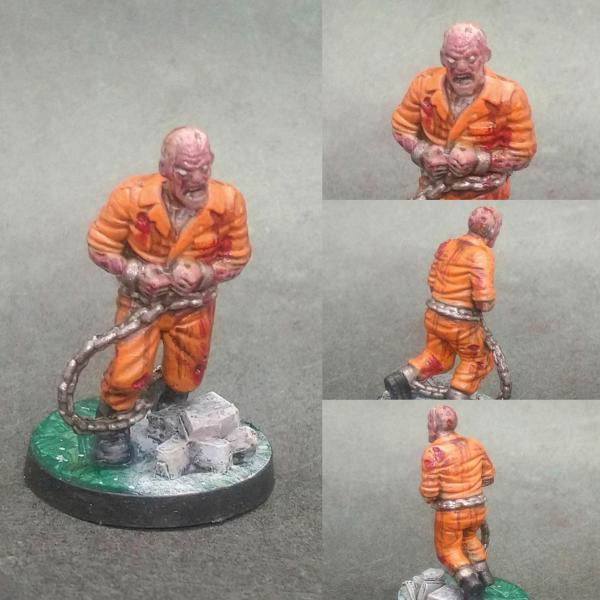

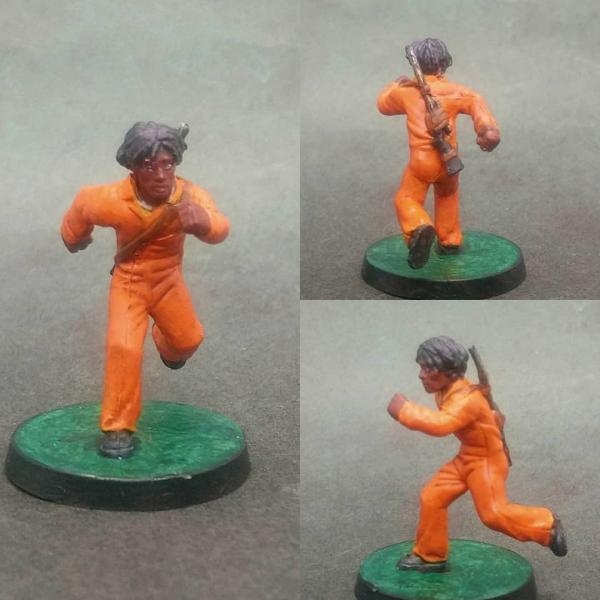

Santa bought me Safety Behind Bars. ?

And I got some painting in over the holiday with a couple of Foundry minis

January 4, 2020 at 11:23 am #1468489

January 4, 2020 at 11:23 am #1468489Continuing with my visit to the world of 1938 A Very British Civil War amd the second part of the Left and People’s Armies.

The Communist Party of Great Britain’s Forces

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) were the British section of the Communist International (Comintern) based in Moscow. This link brought both advantages and disadvantages. The fighting forces lead by the Communist Party of Great Britain had access to the military expertise of the international communist movement including the recently bloodied International Brigades, and to the military resources of the Soviet Union. Thus only the Communists were able to create field forces capable of meeting the British Union of Fascists Legions or regular forces loyal to king Edward VIII. The communist forces thus became a home for non-Communists who wished to take the fight to the enemy and recruitment soared.However, the subordination to the Comintern meant that other anti-fascist factions were deeply suspicious of their activities and motives; the recent experience of the Spanish Civil War sowed doubt in the minds of the Communist Party of Great Britain’s potential allies. The emphasis placed on discipline and political conformity meant that while the Communist forces were the most conventionally military in appearance and organisation, the fear that they served a foreign authoritarian power reduced their appeal.

Militarily, the Communist had a long experience of fighting fascists. With the formation of the Mosley Government, the Communist’s moved to forming fighting squads of party members and supporters; comrades and friends in contemporary Communist Party of Great Britain jargon. The fighting squads were armed in the usual ad-hoc manner, until arms supplies from the Soviet Union began to enter Britain via the ports, including Liverpool, Portsmouth and Whitby, effectively controlled by the Popular Front forces.

These early squads were mixed gendered and were large sections about 20 strong, commanded by an Officer and Non Commissioned Officers appointed by the Party and supported by a Political Commissar; there was no nonsense about elected officers in the Communist Party of Great Britain forces. The commissars were a combination of welfare officer for the troops and political enforcer of the Party Line. The squads were reasonably effective in both attack and defence, but somehow seemed to lack the dogged defensive spirit of the Workers Defence Corps or the reckless abandon of the Worker’s Army. Their critics said they lacked initiative and would not act without central direction from the Party.

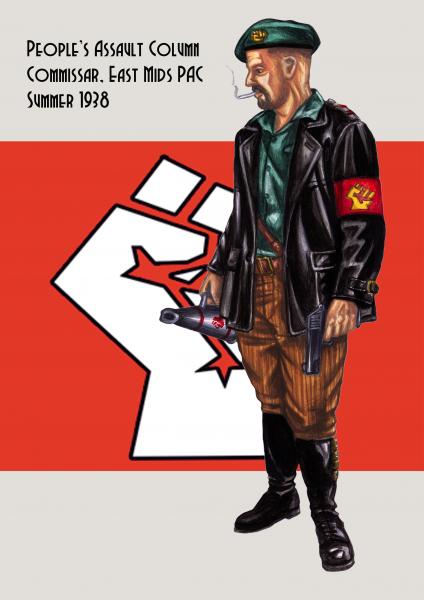

People’s Assault Columns

As the crisis deepened the Comintern decided to develop forces in Britain capable of waging mobile, attacking warfare. In November 1938 the English-speaking remnants of the International Brigades that had been withdrawn from Spain in October were redirected to Britain and, reinforced with fresh arms and equipment from the USSR and new recruits, became the core of the People’s Assault Columns. British recruits were formed into similar columns, which became the best equipped and uniformed of the left’s forces.The appearance of the columns was self-consciously military. Not for them the bohemian look of the Worker’s Army or the armed civilian style of the Defence Corps. Taking their lead from the International Brigades, khaki uniforms were acquired from around the world, complete with overcoats, berets or side caps, steel helmets from a number of sources, while officers and commissars wore black or brown leather jackets in a variety of styles. Women were excluded from the ranks. Each battalion had its own standard, which was presented at a ceremonial parade. Of all the left forces, only recruits to the Assault Columns were taught drill. While not the Brigade of Guards, the Columns were identifiably regular soldiers, as understood in the 1930s.

Organised along the lines of the International Brigades, with clear rank and command structures, including Commissars, the Assault Columns consisted of three or four companies per battalion with three or four battalions per column. Often one ex-International Brigade battalion would be brigaded with two or three new British battalions. At Column level, Soviet advisers discretely gave advice and ensured that the interests of the USSR were never forgotten. Artillery usually consisted of mortar sections at Battalion level, while motorised transport consisted of a mix of commandeered commercial vehicles. However, this was far superior to the rest of the left’s forces.

Tanks were supplied by the Soviet Union, never in great numbers and crewed by Red Army personnel. The T26 and BT5’s supplied were formed into sections of three with three sections per platoon. These platoons were seen as strategic assets and were allocated to offensives as and when needed; the agreement of the “Comrade-Adviser” was always needed before their deployment. Given the ad-hoc nature of the Crown’s forces, and the quality of British produced Armoured Fighting Vehicles in this period, the Assault Column’s armour and Soviet anti-tank artillery, were formidable opponents.

January 4, 2020 at 11:23 am #1468490January 4, 2020 at 8:50 pm #1468544

January 4, 2020 at 11:23 am #1468490January 4, 2020 at 8:50 pm #1468544Happy New year.

First project of 2020 finished. ?

Safety Behind Bars Expansion minis (6) finished well enough to get playing.

January 5, 2020 at 8:06 am #1468570

January 5, 2020 at 8:06 am #1468570Irregulars

While building up a field force, the Communist Party of Great Britain and the Comintern considered those areas in which the forces of the Crown were dominant. Rather than leaving such locations to the mercies of the British Union of Fascists, small groups of highly motivated individuals were sent behind enemy lines, to carry out irregular action, including sabotage, assassination, the Workers Army claimed the targets included their members, and general disruption. Inevitably, the British Union of Fascists countered with reprisals and hostage taking; far from being universally popular, the Irregulars were sometimes bitterly hated by the civilians in the areas affected. The Party’s network of members ensured that the Irregulars continued to operate and Crown forces were dispatched to patrol behind the lines.Thus, the Irregulars performed a strategically important role.

Conclusion

By the winter of 1938, Britain was ablaze, from the Fife coal fields to the Channel ports, from the South Wales Valleys to the Norfolk Broads, forces fighting against King Edward VIII and Prime Minister Mosley, and for various visions of a better, socialist future were engaged. Towards the end of 1938, three People’s Assault Columns were positioned in Portsmouth, Liverpool and North Yorkshire. An offensive designed to “crush the Mosleyite vipers” once and for all could not be far off.

January 5, 2020 at 11:26 am #1468577

January 5, 2020 at 11:26 am #1468577Kastellan Robots and Cybernetica Datasmiths for my 40k army. Full project here: https://www.beastsofwar.com/project/1427037

January 5, 2020 at 9:36 pm #1468702

January 5, 2020 at 9:36 pm #1468702

Finally getting the time to work on my DAKJanuary 6, 2020 at 1:25 am #1468725January 6, 2020 at 7:13 pm #1468881

Finally getting the time to work on my DAKJanuary 6, 2020 at 1:25 am #1468725January 6, 2020 at 7:13 pm #1468881Finally finished a Blood Angels assault squad that had been sitting on my to-do shelf for almost 10 months!

More on my usual hobby project! 🙂

January 6, 2020 at 8:16 pm #1468898Coming to the end of my journey with a little bit of background history into the events that started 1938 A Very British Civil War.

Background to 1938 A Very British Civil War

The Crises in Monarchy and Government

On November the sixteenth 1936 His Majesty Edward VIII invited Prime Minister Baldwin to Buckingham Palace. The matter for discussion was the King’s intent to marry the American divorcée Wallis Simpson. The Prime Minister indicated that the Government would not and could not support Edward’s marriage, telling the King that if he wished to marry Mrs Simpson he must abdicate. If the King refused the Government would be forced to resign. Prime Minster Baldwin already had it from the other political parties that if that was the case they too would refuse to form a Government. A constitutional crisis loomed.

By the end of the month King Edward VIII, buoyed up by the support of the “King’s Party” of politicians and aristocrats, chose to call Baldwin’s bluff. On December the seventh he summoned Prime Minister Baldwin to an audience at Buckingham Palace and informed him that he saw no reason to give up his affections for Wallis Simpson or his throne and so would do neither. With a heavy heart and true to his word, Baldwin tendered in his resignation. Over the next few days, and despite his best efforts, Edward was unsuccessful in persuading the leaders of either the Liberal or Labour parties to agree to form a Government. Even Winston Churchill, a long-time friend and the most prominent member of the King’s Party, refused the post, recognising that public support for the King was on the wane.

Mosley as Prime Minister

Finally, King Edward VIII turned to his friend Sir Oswald Mosley. Mosley, who had held a Government post in the past but, was not in Parliament at this time, agreed to Edward’s offer and on December the eleventh his appointment as Prime Minister was announced by the Palace.

His unelected status, as well as his extremist politics caused outrage in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, with members on all sides of the political spectrum walking out. Although under pressure from Mosley, Edward was keen to maintain as much of the governmental system as possible and so refused to dissolve Parliament. Instead those MPs and lords who did not take their seats were merely recorded as absent, and the Mosleyite Government presided over a rump parliament of pro-monarchists and men who felt it might still be possible to influence government through the regular channels.

The appointment of Mosley as prime Minister sparked major protests across the country. An Autocratic Monarch and a Fascist Government combined to bring out even the most moderate. In areas where fights between socialist and right wing organisations had already been regular occurrences, such as Newcastle and the East End of London, the violence became ever more extreme as Mosley’s party, the British Union of Fascists, feeling more secure with their leader at the head of Government, sought to end the Socialist Movement once and for all. A rapid escalation saw many inner city areas divided along factional lines, with barricades being erected and armed men launching raids into rival zones.

1937 The Purging of the Guards

By the end of February 1937 it was clear that the regular authorities were unable to cope with the levels of violence and protest. There were increasingly desperate calls from the Chief Constable of various areas for armed support. King Edward VIII was unwilling to use soldiers against his own people and unsure that the army, many of whose officers were distrustful of Edward’s pro-German sympathies, would obey such an order. Instead he granted approval for the raising of Auxiliary Constabularies, equipped and structured along military lines and financed by the War Department, who were to “assist and support the regular police authorities in disbanding militant organisations and restoring order”. Whilst their deployment gave the authorities the upper hand to begin with many saw them as an example of Personal Rule and, remembering the reputation of the Black and Tans in Ireland, resolve hardened and previously quiet areas saw protests and violence.

It was an obvious and simple act that finally resulted in the unrest in England becoming a full blown civil war. On the twelfth of May the Edward VIII attended at Westminster Abbey for his coronation. Security was incredibly tight and whilst soldiers of the Guards regiments lined the route form Buckingham Palace to the Abbey it was the Metropolitan Auxiliary Constabulary, made up predominantly of Fascist party members and already being recognised as ’Mosley’s Legion’ who stood behind them watching the crowd.

The King was traveling in a closed car; the traditional state coach had been deemed too risky a proposition. As it turned into Parliament Square shots were fired – some said from the crowd, others claimed it was Guardsmen or even the Auxiliaries. The result was pandemonium. The car roared off for the safety of the Houses of Parliament whilst the Auxiliaries started randomly firing into the crowd. The guardsmen turned on the Auxiliaries and for about a quarter of an hour the square was a battleground between the two, before senior officers were finally able to restore order.Almost immediately Edward instructed Mosley to declare martial law. All major cities were brought under a curfew and the Auxiliaries were given even stronger powers. The King and Wallis fled to the safety of Madresfield Court, a stately home near Worcester.

In the days following the assassination attempt rumours over who fired the shots was rife. Amidst claims that they had been the ones to open fire on the King Edward and Mosley had the British based battalions of the Scots, Irish and Welsh Guards disbanded entirely. Whether or not any of the soldiers had been responsible for the attempt on Edward’s life, all had had their honour impugned and, left without jobs and prospects saw this as a stab in the back.

Ironically the declaration of martial law had seen the militarisation of a number of left wing and anti-monarchist forces, including the Anglican League, as they sought to protect themselves from the attacks of the Auxiliary Constabularies, who were tasked with shutting them down. Mosley and Edward finally deployed Regular and Territorial Army units in an attempt to quieten the counties. As part of a conciliatory approach it was decided that the regiments should remain in their home counties in order that the sense of armed invasion by outsiders should be minimised. It was to prove a costly mistake for the government.

January 6, 2020 at 10:44 pm #1468951January 7, 2020 at 1:07 am #1468978January 7, 2020 at 3:15 pm #1469161January 7, 2020 at 3:40 pm #1469181

January 6, 2020 at 10:44 pm #1468951January 7, 2020 at 1:07 am #1468978January 7, 2020 at 3:15 pm #1469161January 7, 2020 at 3:40 pm #1469181Continuing with the final stages of my journey around the world of 1938 A Very British Civil War today I bring you more about the background to why the civil war started.

The Empire and Nation Fragments

King Edward VIII’s decision to marry Simpson caused a crisis not just in England but across the Empire as well. In Australia and New Zealand the Governments fell and new elections were called. The nationalist Governments of South Africa and Ireland used it as a pretext to finally separate themselves from Britain and the Commonwealth. De Valera, the Irish Prime Minister, also used it as an opportunity to send troops into the Province of Ulster, purportedly to help restore order and protect Eire’s borders but in effect to annex the north. The King’s brothers and their families, unwilling to become embroiled in the political furore retreated to Canada.

In India the crisis gave the independence movement cause for joy. With the British government in crisis they felt sure that they would have a freer hand. The Viceroy saw what was coming and with skilful diplomacy managed to work with the Congress to maintain the status quo during the early days of the crisis.

The fragmentation of Edward’s realm did not take place entirely overseas. Edward’s decision to marry Wallis Simpson caused a split in the Anglican Church with a majority of the Church Assembly, led by the Bishops of Hull and Bath and Wells, declaring the King unfit to act as the head of the church and forming an Anglican League aimed at replacing him with his eldest brother.

This in turn led the General Assembly of the Scottish Kirk to form a Council of State (made up of MPs, Peers, civic dignitaries and army officers from Scottish regiments) which, using the medieval Declaration of Arbroath as its template, announced that Edward was an unfit King and that Scotland would no longer recognise his rule nor that of the London Parliament. It went on to call upon all Scotsmen to assist in removing the taint of Fascism from Scottish soil. The regiment of the Scots Guards were welcomed back with honour and a number of Scottish regiments followed their example, mutinying en masse. Those battalions not serving overseas were led by their Colonels and, acting with the local authorities, forcibly disarmed and expelled the British Union of Fascists and Auxiliaries. By the end of 1937 the Council had officially closed the border with England.

Wales became divided. In the north a long tradition of anti-English sentiment formed the basis for a Welsh independence movement which sought to replace the Crown with a Welsh Republic. In the South however the sentiment was far less strong and, whilst many were unhappy with the King both on religious grounds and over the appointment of Mosley, the instinct was to remain loyal to the Crown. Edward’s advisers wanted to maintain access to Welsh Coal stocks but still treated the Welsh with suspicion fearing a repeat of the Scottish Crisis. The disbanding of the Welsh Guards heightened tension following the assassination attempt on the Royals. But in Edwin Lloyd-James, Mayor of Cardiff the south of the Principality found a leader who had insight and ability and who was prepared to be completely ruthless. Seeing how far things were deteriorating in the Principality, with the North in the hands of the nationalists, Westminster making noises about sending in troops from London and many of the mining villages setting themselves up as independent socialist communes, he welcomed home the Welsh Guards with a parade and had them based at Cardiff Castle. Their pay was picked up by the City and as far as possible their honour was restored. In return Lloyd-James had a superior military unit under his direct control ready to respond to any Nationalist threat.

Liverpool and Cornwall

Meanwhile the Nationalists had not been slow in organising, and were receiving considerable support from across the Irish Sea. Irish Republican volunteers travelled to Anglesey to meet Welsh leaders. This marked the start of a regular traffic of volunteers and advisers keen to open a second front against the British. Sympathetic individuals within the Irish Government and army were also prepared to covertly supply the Nationalists. As the guerrilla war began Nationalists infiltrated the south, attacking economic targets. The Guards provided a good defence but inevitably some operations succeeded and put further economic pressure on the south. As the first Irish prisoners were taken Lloyd-James realised this was now more than a simple internal struggle and he needed to find a way to take the war back to the Nationalists rather than remaining on the defensive. As a result he entered into talks with the Irish right-wing Blueshirts organisation. Although not any more positive towards the British Government than the Republicans, the Blueshirts welcomed the encouragement to continue their fight against the Irish Government and IRA onto Welsh soil. Consequently companies of Blueshirts were let loose in north Wales with the mission to hunt down the Nationalists and their Republican allies. A long and bitter conflict began, but it moved some of the focus away from the vulnerable south giving Lloyd-James a breathing space allowing him to turn his attention to the smaller but well entrenched socialist miners’ militias.

In Liverpool there had been considerable protest against the British Union of Fascists, culminating in a Dockers’ strike with men refusing to unload supplies and goods destined for the regime. British Union of Fascists units from Manchester arrived to break the strike and take over the city council.

Led by Socialist Mayor Henry Walpole large numbers of demonstrators took to the streets to oppose the Fascists. Peaceful protest turned to pitched battles and the Fascists soon found themselves outnumbered and driven back. The British Union of Fascists leaders called for support from Auxiliary Constabulary, but when these too gave way the army was called for. The Liverpool Regiment were the first on the scene. Ordered into the city centre they faced a crowd of several thousand still led by the Mayor. When the crowd refused to disperse the order was given to open fire. The officers of the Liverpool Regiment hesitated and then ordered their men to stand down. At this point a delegation of officers approached the Mayor and offered their services to the people of Liverpool. Not all military units followed the Liverpool Regiment, some returned to their barracks whilst others continued to support the British Union of Fascist and Auxiliaries. Liverpool’s mayor declared it a Free City, arguing that it would not participate in the madness of the rest of the country.In scenes mirrored across the counties of England Cornwall had split into a variety of small factions. Civic and religious communities were split over loyalty to the Crown. A minority still backed the king but could not support a British Union of Fascist government, while a more vocal majority argued to follow Scotland and Liverpool in seeking independence. Police units proved totally incapable of checking an increasing spiral of violence and so the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry were deployed along the Tamar with the mission of keeping the factions apart.

A nationalist militia was formed and became known as the Army for Cornish Liberation or the Kernow Liberation Army. In response Royalist agents supported the more pro-Edward party by creating a rival Cornish Democratic Royalist Party with its own militia.

-

AuthorPosts

The topic ‘What Are You Painting Now?’ is closed to new replies.

![Very Cool! Make Your Own Star Wars: Legion Imperial Agent & Officer | Review [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2025/12/Star-Wars-Imperial-Agent-_-Officer-coverimage-V3-225-127.jpg)