Centennial Gaming In The Great War – The Campaigns Of 1918: Part Two

April 30, 2018 by oriskany

We have returned, Beasts of War history fans, to our continuing series on the 1918 campaigns of World War One. Specifically focusing on the spring and summer of 1918, my friend Sven Desmet (BoW @neves1789) is taking a wargaming look at the 100th anniversaries of these engagements, which in many ways changed the face of war.

Read The Series Here

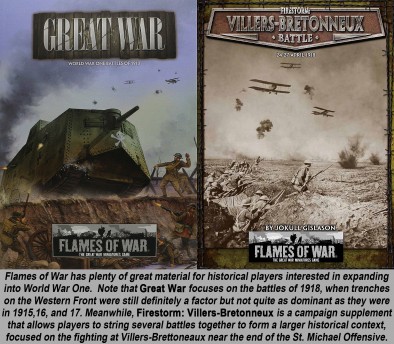

In Part One last week, we introduced the project and summarized the Great War up to this point. We also looked at some of the “mechanics” of Great War combat (i.e. trenches, artillery, and machine guns, railroads), and took a first look at how these work on the tabletop (specifically, Flames of War “Great War”).

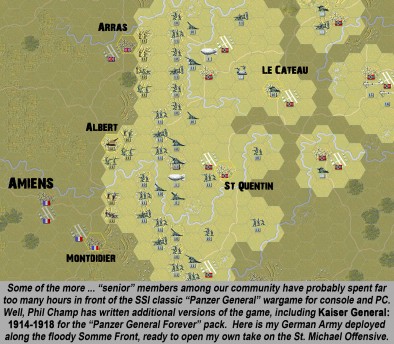

So now it’s time to “go over the top” and get started with the actual battles of 1918. We’ll start with the “St. Michael Offensive” of March and April 1918, looking how the Germans hoped to finally shift the war decisively in their favour. More importantly, we’ll look at how actions in this offensive can play out on the 15mm table.

The St. Michael Offensive

The Clock is Ticking …

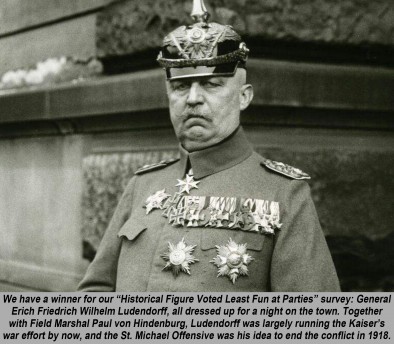

The St. Michael Offensive - also called the Ludendorff Offensive or the “Kaiserschlacht” (Kaiser’s Battle) - was a massive German attack on the Western Front starting in March 1918. The goals and concept for the offensive become clear with a brief overview of Germany’s strategic imperatives in the fourth year of the Great War.

At the outset of 1918, Germany was faced with a “good news, bad news” situation. On the positive side, Russia had dropped out of the war after a string of cataclysmic defeats and the Bolshevik Revolution. The Germans had finally broken free of their classic strategic dilemma, the two-front war.

The Central Powers had also frustrated attempts by the Western Allies to start “second fronts” at places like Gallipoli and at least for the moment, Austria-Hungary was holding the Italians in the south. As 1918 opened, the Germans could focus solely on the Western Front, giving them a momentary numerical advantage over the British and French.

The bad news was that the Americans had entered the war in 1917. For now, it was taking the Yanks time to raise an army, ship it across the Atlantic, and integrate with British and French armies already in place. But later in 1918, the Germans knew they’d see the numerical balance shift irrevocably against them.

All these factors led the German Imperial Staff to an inescapable conclusion for early 1918. In order to get any kind of favourable result out of the war, the deadlock in the trenches would have to be broken now. The Western Allies had to be dealt a crippling blow before the Americans could tip the scales against Germany forever.

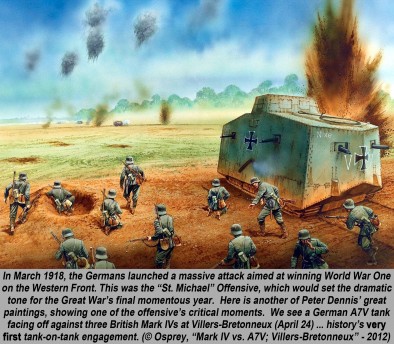

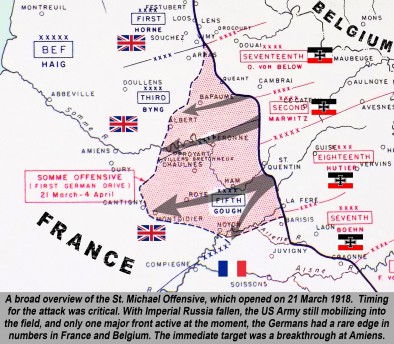

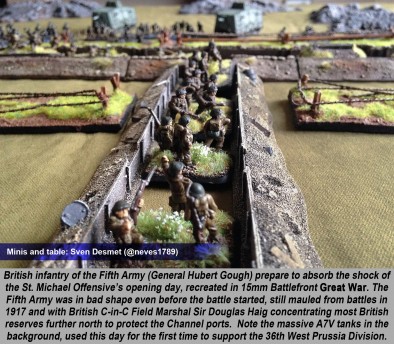

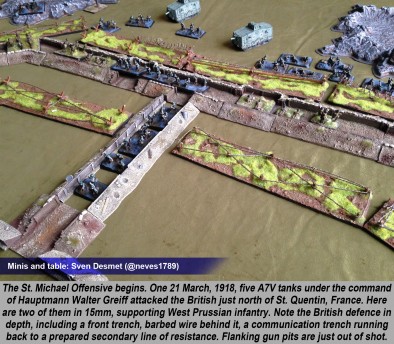

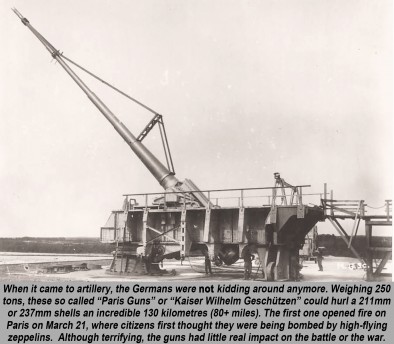

Named after Germany’s patron saint, the St. Michael Offensive launched on March 21st. For five hours, over 6,500 guns and 3,500 mortars plastered the sixty mile front of the British Third and Fifth Armies along the Somme. Then, sixty-five divisions of the German Second, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Armies shoved forward.

The British reeled back, their Fifth Army, in particular, taking hideous losses. At least for the moment, the Germans seemed to have finally broken the trench stalemate with the largest territorial gains since 1914. A big factor in this success was the use of new “stormtrooper” units and tactics, which Sven discusses in more detail below.

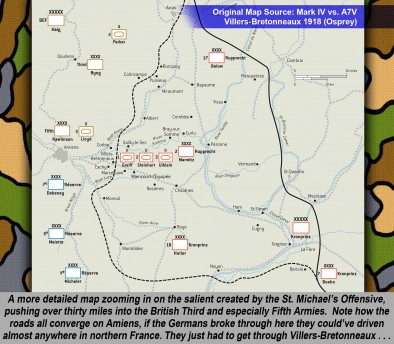

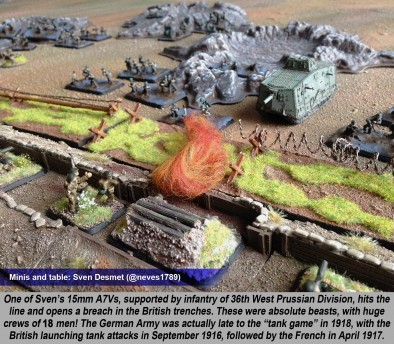

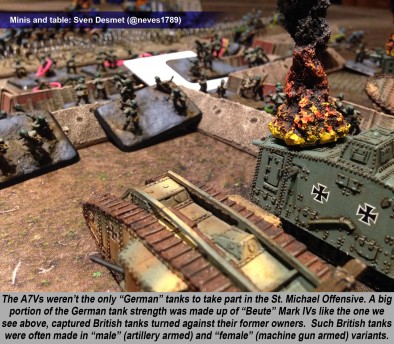

The German objective was a breakthrough at the city of Amiens. But they were finally halted just short of this target in a series of battles around the town of Villers-Bretonneaux, a landmark moment because it would see history’s first true “tank engagement” - with opposing tanks actually firing on each other in combat.

Yet despite desperate efforts, the Germans would fail to break through to Amiens. Thus, other offensives would have to be launched, covered in Parts Three and Four of this series.

Sven Gets Down To Details

Not Just A Military Necessity

As Jim has pointed out; this was the big one for the Germans and they knew it. This offensive had been planned not only to get a military victory but to end the war and dictate the peace. Or at least come to the negotiating table as equals...

The situation at the German home front had made it clear that the war could no longer go on, both politically and economically. The Social Democratic Party was gaining support against the war and gradually swaying public opinion against the military dictatorship of Ludendorff and Hindenburg.

Fuelling this growing feeling of dissent was the deteriorating economic situation. Since 1914 the British Navy had been blockading German ports and preventing foreign products, including food, from entering the country. By 1918 hundreds of thousands of civilians would have been starved to death.

Bewegungskrieg/War Of Movement

One of the defining aspects of the St. Michael Offensive would be the speed at which the Germans broke through the line. In 1806, The Prussians had learned what speed meant at the hand of Napoleon and had studied this aspect of war throughout the 19th Century.

Generals like Clausewitz, Moltke and Schlieffen had passed on their views on warfare to the World War One generation of Prussian officers. So really most German generals (disregarding Falkenhayn) had not forgotten that war was all about movement, it’s just that the stalemate got in their way.

For their last big strategic offensive, they would have to apply all the lessons from the previous years to force a decision. If there ever was a do or die moment for the Germans during World War One, then this was it.

Innovation

In Part One we saw how trench warfare had been around for centuries and how industrialised warfare had led to a stalemate. The operational and tactical advantage had shifted to the defender. The many failed offensives of both sides had shown how costly in lives that could be.

Before we dive into the actual offensive, we’ll take a look at the innovations that the Germans had developed throughout the war. Ludendorff himself had already published writings on both defensive and offensive tactics in positional warfare in 1917-18 and had these taught to his subordinates, sometimes down to company level.

One of the bigger innovations came from the artillery officer Georg Bruchmüller. He had successfully commanded large artillery formations on the Eastern Front during the Russian Brusilov and Kerensky Offensives in 1916 and 1917. Unlike the Allies, who favoured long artillery barrages, Bruchmüller advocated short intense barrages. He would eventually be known as Durbruchmüller; Durchbruch meaning breakthrough in German.

These were less aimed at destroying the entire frontline and causing mass casualties but trying to disrupt the enemy as much as possible. His barrages would only last five hours and used three phases. First, attack the enemy troops with gas. Then hit their guns with a mix of gas and high explosives, and lastly a creeping barrage of high explosives to screen the German infantry attack.

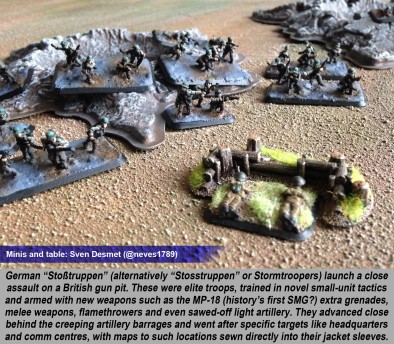

The other German innovator was Oskar von Hutier; a German general who had served in the west and east since 1914. He had studied enemy tactics like the successful Russian Brusilov offensive of 1916 where the Russians had penetrated the Austrian line at their weakest points using smaller, specialised units. Von Hutier would take this approach and formed the now famous Stoßtruppen or stormtroopers.

One of the main tactics employed by the Stoßtruppen was infiltration. They would follow the creeping barrage into the enemy trenches and push beyond, ignoring strongpoints to isolate and surround them. Reserves would push into these breaches instead of onto the strongpoints as had been the case in earlier battles like at Ypres or Verdun.

The close combat power of the Stoßtruppen was also increased through the use of the lighter MG-08/15 machine gun and the famous submachine gun, the MP-18. However, most Stoßtruppen were equipped with pistols, hand grenades and close combat weapons like knives and spades...all intended to maximise shock upon the enemy and keep the offensive going.

Putting It Into Practice

All these theories culminated on March 21st, 1918 with the start of Operation Michael. Ludendorff put the centre of his offensive on the Somme at the point where the French and British armies met and tried to drive a wedge between the Allies. The German Eighteenth Army under von Hutier pushed southwest to drive the French from the Aisne and threaten Paris for the first time since 1914.

Meanwhile, the German Seventeenth and Second Armies pushed the British Fifth Army back from the Somme and aimed at the important rail hub at Amiens. Capturing this town would severely hinder the Allies lines of communication and might even see the British thrown out of the continent.

Indeed the British suffered heavy casualties as the new German tactics wreaked havoc on the regular British soldiers.

In fourteen days the German Stoßtruppen had broken past the trenches, pushing sixty-five kilometres (forty miles) into the open fields beyond, an astronomical distance by Western Front standards. Allied resistance, however, had not completely crumbled and all these gains did not come without a cost. Many of the best trained and experienced German troops had now been killed or wounded or were simply exhausted.

When after two weeks, the offensive came to a halt, the Germans found themselves in an overextended salient with the Allies recovering and reinforcing. The offensive had failed to reach its strategic goal and stalemate had returned. They would, however, keep up the offensives as we’ll see in Parts Three and Four.

In Flames Of War: Great War

Flames of War Great War brings the Stoßtruppen to life through a number of special rules and equipment that reflect their character and allows players to recreate the St. Michael Offensive. A Stoßkompanie or assault company is equipped with pistol and MG teams and the odd SMG and flamethrower.

They give the player the option to perform a night attack, making everything harder to see and hit. They can also use the spearhead rule, allowing them to deploy further into No Man’s Land. Combined with a “Fearless Veteran” rating, the best in both skill and morale, it makes these guys tough as nails on the tabletop.

The scenarios covered in the book perfectly suit the St. Michael Offensive, going from a standard trench attack through to a more mobile battle for the second line and then eventually the green fields beyond. This also works great as a mini-campaign like my Great War opponent (@Erik101) and myself have been playing.

In Part Three we’ll be taking a look at how the Allies countered these tactics and how artillery and tanks played a role both in real life and on the tabletop. The last big German strategic offensive had failed, yet it still had not brought an end to the war...

Oriskany’s Debrief

We hope you’ve enjoyed this second look at centennial gaming in the Great War. Have you tried any “storm trooper” tactics of your own? How would you handle a trench breakthrough in your wargaming?

Post your questions, feedback, and comments below, and keep the conversation going!

"At the outset of 1918, Germany was faced with a “good news, bad news” situation..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"One of the bigger innovations came from the artillery officer Georg Bruchmüller..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

![TerrainFest 2024 Begins! Build Terrain With OnTableTop & Win A £300 Prize! [Extended!]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2024/10/TerrainFEST-2024-Social-Media-Post-Square-225-127.jpg)

Very informative article. I feel the urge to start painting some 15mm WW1 figures, fortunately I have a load awaiting paint from the Great War Kickstarter.

Thanks very much for kicking us off, @gremlin ! I’m noticing that many of the 1918 WW1 15mm figures looks very similar to 1940 BEF and French Army figures, even the Germans look very similar in 15mm (at least early WW2). The tanks and artillery, however, of radically different. I might get a 15mm A7V just as a display piece, with that huge block shape and the rivets, it’s just such a beautiful disaster to look at at. 😀

Thanks! They’re great fun to paint, the 15mm scale just works so well for anything around company level.

Another great article! Interesting how the outcome in World War I seems to be in doubt much later than it was in World War II. Looks like @oriskany and @neves1789 make a great team!

Thanks very much, @pslemon ! There’s actually a third person that should be in these credits,@neves1789 mentions him in his text and I could have sworn I put him in the photo credits – that’s @erik101 . I’ll have to check my originals, I was certain I re-uploaded replacement images with his name in those blue credit bars, but I might be losing my mind again. Half the miniatures and terrain in those WW1 table photos are his, though, and we want to make sure he’s recognized for his part in helping Sven and I put this series together.

Thanks for the reply! Working with @oriskany has been awesome 😀

I also just noticed that @erik101 wasn’t mentioned on all the pictures but I’m sure he won’t be too upset 😉

Here’s what happened – I was under the impression that @erik101 ‘s miniatures were in the photos with French and German troops in Parts 01, 03, and 05. These were photos @neves1789 took for me after I realized we needed British troops featured in the St. Michael / Georgette offensive material.

So if some of these British minis in Part 02 are his, I do apologize.

No worries @oriskany, it’s only the last picture in fact that was taken with his terrain, though it’s only showing my mini’s. 😉

I don’t think after 1914/15 the result was in doubt. I think it needs mentioning what the British blockades of German ports was achieving and even Ludendorff realised something needed to be done before the German people rose in revolution in their opposition to the continuation of the war

Thanks @torros 😀

>>>>

Correction to my earlier correction re: @erik101 🙂 (apparently I’m still asleep this morning) – His miniatures were in the photos with French and German troops in Parts 01, 03, and 05. These were photos @neves1789 took for me after I realized we needed British troops featured in the St. Michael / Georgette offensive material. The photo credits are in fact correct. 😀

another great article 🙂

Thanks very much! 😀

Thanks @commodorerob ! You’ll be pleased to hear we’ve managed to get some naval action in part 5 😉

Do the Entente get the Spearhead rule as well?

I would defer to @neves1789 on this one, but I don’t think so. From WWPD page on FoW Great War: German Army Lists: they seem to single out Stoss platoon for “Stosstactik” and “Spearhead” rules. Hardly conclusive, of course. The Stoss Platoons. What many German players are going to be drooling over. These boys are fairly pricey, and are always Fearless Veterans. So the basic buy is 6 pistol teams and a MG team. You can add an additional pair of pistol and MG teams, and also add a flamethrower. The command pistol can be swapped for a SMG. All… Read more »

No, although they get some other special rules. The French get Quick Fire, rerolling failed hits with their 75’s and They Shall Not Pass, rerolling failed counterattack tests. The British get British Bulldog, also rerolling counterattacks. The Americans get rerolls on their unpinning tests and don’t need command teams to assault.

The mission specific rules offer more flavour though and really give the game a WW1 feel.

I think it bears noting (at least I’m pretty sure on this) – that Battlefront was going for a 1918 feel for these rules. The mechanics and dynamics for a battle taking place in, say, 1914 would be quite different.

Oh absolutely! I’d even dare using an ACW ruleset for 1914 ^^

There is a rule set called Bloody Big Battles which covers mostly 19th century large battles but it has been adapted to the Balkan Wars and the early days of WW1. Its basically a cut down version of Fire and Fury but although I haven’t played it myself seems to have a small but loyal following

“I’d even dare using an ACW ruleset for 1914” – with a few mods, yes. From what I understand belt-fed machine guns like the Vickers, Maxim, and MG08 were in use, but few enough that a little tweak in the rules or adding a new unit for “machine gun companies / battalions” (depending in the scale in question) would probably straighten that out. Repeating rifles of late ACW might be close enough to bolt-action rifles of 1914 for an approximation. Care has to be taken, though, battles like 1866 Königgrätz show the devastating difference between even rudimentary breech-loading weapons and… Read more »

@oriskany you wouldn’t have to worry too much about Machine Guns in 1914 since everyone except the Russians only had two guns per Battalion. The Russians had 8 but since officers were responsible with their lives if anything happened to the gun they tended to be pretty far away from the action.

I would just increase a unit’s firepower to represent the two MG’s. Breech loading artillery is very tricky though.

@elessar2590 – *** “you wouldn’t have to worry too much about Machine Guns in 1914 since everyone except the Russians only had two guns per Battalion.” Right, this is pretty much what I was thinking. My only question would be about separate MG units (not in the battalions, but in their own) which so many armies seemed to embrace in earlier years. Whether this would be a factor in 1914 I honestly don’t know, I don’t THINK so, but wanted to leave it open as a possibility in my original reply. Breech loading artillery, yes. In most unit-based games (as… Read more »

@Oriskany Bloody good article again, Always amazed at how a simple idea like the Stormtroopen worked, we off course know it was used again and with armour in WW2,

Be interested to read the next bit on how they countered it,

Like a lot of my historical reading, did it ages ago so nice to get a refresher,

Particularly as I’m considering doing a Masters degree on War studies in the next year if I can sort out the pesky living expenses thing.

I think it needs remembered the Germans lost a lot of men in Operation Michael ( I think about 200,000) Probably their best troops to be honest that they were going to be hard replacing that experience. A bit like the initial attacks in 1914 they tired themselves out and found it harder and harder to resupply as the days wore on

Very true. This is all covered in future segments, especially the Spring Offensive / Kaiserschlact overview of Part 05.

Am I jumping ahead too much Jim?

No, @torros, I just wanted to make sure our readers knew we didn’t “miss” this. We are limited in how big we can make these articles, and therefore can only include so much information per article. The series is developed and produced as a body (and even then of course we can’t get everything). But rest assured, we do get to this. Meanwhile, if we don’t address perceived omissions, people get the wrong idea. It’s an unfortunate side effect of publishing in a “sniper-rich” environment of the internet. Everyone has to prove how well-read they are (short of putting int… Read more »

Thanks very much, @bobcockayne – Always glad when people appreciate the effort myself and other content creators put into a project like this. Like most great ideas, military or otherwise, the success of things like the stormtroopers comes not in its “high concept” but in the details of its execution. “Greatness comes not is doing extraordinary things, but in doing simple things extraordinarily well.” Aircraft, tanks, poison gas, that’s all fine, but as late as 1918 Germany was practically destroying whole British armies (Fifth, for example and almost the Third) primarily with much older tools like infantry and artillery, just… Read more »

@sven must not forget to give you praise for your bit,

Haha thanks 😀

That master’s degree sounds real interesting, does it specify on a historical period or is it more based toward modern application?

How inspiring. There is one thing I want to mention first, and this is the accuracy with which things are described and explained here. This is truely splendid, and for this I will confer the “Pour le Merite” to both @oriskany and @neves1789 . And that´s even before I read the last three parts. 🙂 One of my historical sources has it that even if from 1917 onwards the eastern front didn´t see much or any fighting any more, still there were around a million men locked down there. I wonder if the offensives 1918 had been successful had those… Read more »

@jemmy – wow the Blue Max? I don’t know if I deserve that. I know @neves1789 does, but I think we already gave him the “Croix de Guerre” as well. This guy won’t be able to stand up soon under all his medals. I’ll settle for the World War I service medal, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_I_Victory_Medal_(United_States) … with bronze star for second award (after our “Heroes of Limanowa” article series last year). Yes, both Sven and I have been working very hard to ensure our accuracy is at the highest possible standard. I say possible because we are limited in size and length… Read more »

The Russians had serious problems coming to the table since the Bolsheviks wanted peace but didn’t want huge chunks of Russia leaving the nation and the Germans at one point in 1918 did reoccupy Russian territory. The Germans wanted to split as many countries from Russia as possible and used that as the excuse to keep the pressure on. The Germans were also pretty involved in the war in Finland with Mannerheim preventing the new nation from falling to Communism. The Russians only real threat was “if you don’t give us peace we’ll start a Communist Revolution in your country”… Read more »

Thanks very much, @elessar2590 – yes, I have read that, where on his return to Russia, Lenin apparently traveled by closed train through parts of Germany and along the way made a pit stop for a hefty piece of German funding to cause problems in Russia … definitely an embarrassing secret the Bolsheviks wanted hidden in the late teens and early 20s (Russian Civil War years). I did not know about the Germans involved in Finland. Was this during World War I or afterwards during the RCW / Friekorps era? I honestly don’t know. My friend @aras has a lot… Read more »

During the war. The Finnish Civil War was January to May 1918.

Yep and not only did Lenin get his initial backing from Germany he continued to receive German support right up to the Revolution. It actually came out a few weeks before the October Revolution but the Communists managed to keep it quiet aside from the intital week or two before things in Russian went completely insane.

Russia … 1917-1922 … that’s definitely a violent slice of history right there.

Another amazing article guys.

@neves1789 how did you find the Flames of War rules for using Tanks? I’ve played some WW1 Flames but never used tanks. Do the rules feel a little clunky or do they add another layer of period feel?

great stuff guys good to get some meat on the bones as its more WWII I have mostly read over the years.

Thanks very much, @zorg ! I agree it’s always great to expand the topics when it comes to historical wargaming. It’s not like we have a shortage of material or anything! 😀

That’s for sure @oriskany.

🙂

Ok, shame on me! I completely missed the first day of article two.

Another great entry. I have to say I love how much I learn in you articles without getting bored. Though I’m embarrassed to admit that of the thousands of words of well written text and the great table and map shots, my favorite image is of Ludendorf and his title of”least fun at parties” . Poor Germany, it never had a chance with guys like that in charge.

Hey, if you ask me, they were very “kind” to Ludendorff when they made him the villain in the recent Wonder Woman movie.

Oh, Hollywood. ** sigh ** Will you ever actually grow up?

Well history is written by the Victor’s so the won’t be nice to losers They have just defeated.

Well, @zorg , given Ludendorff’s wartime policies, followed by his support and legitimization of Hitler in his early career, I’d say he deserves his “villain status. 😐

He was probably a bit do lally by then?

Well, he helped Hitler in his early days and was present at the Beer Hall Putsch … in fact he was the main political weight and “legitimacy” behind it, so …

Great stuff.

Thanks very much, @c0cky ! 🙂

For me guys this article was way too short. In the same way you see a really good movie but feel you were ripped off as it only went for an hour. Then you look at your watch to see it was actually two and a half hours long. The miniatures look great. With the second installment you really hit the spot, so we’ll done to all of you. Took me a while to get to this installment as I have been busy creating masters, molds and casting them for the Desert project. I have hit a number of auctions… Read more »

Thanks, @jamesevans140 – For me guys this article was way too short. In the same way you see a really good movie but feel you were ripped off as it only went for an hour. Then you look at your watch to see it was actually two and a half hours long. Ha! Thanks very much. We were actually kind of bursting the seams on this one, per the constraints and limitations by which we try to abide for publication. Luckily, we have three more articles in the series, and perhaps another series later in the year (Centennial for Hundred… Read more »

Great read both of you

Thanks very much, @rasmus ! 😀

Thanks @oriskany. Look forward to what Sven has to say about the stormtroops. Funny that they were active for just 3 years yet they are infused in our culture. Mention them to people who literally knows nothing about them and an almost prime ordinal fear stirs briefly in their subconscious. Yes a did catch your 75th actual on Tunisia. Our first focus is on Gazala, @timp764 choice. Here we implement doctrine and tactics of the combatants to test them and better understand them. This goes for the troops and their equipment as well. The leadership gets the same treatment. Then… Read more »

Thanks, @jamesevans140 – @neves1789 has covered the Stormtroopers in this part of the series, in particular when he discusses von Hutier’s observations from the Eastern Front and application into a new German stormtrooper doctrine adopted and applied against British and French formations in the West. Totally agree about the “nightmare image” in the subconscious. This is a point I touched on near the end of the article series interview in last week’s weekender. “This is the 1918 nightmare image of the German Stormtrooper with the steel helmet and face hidden behind a gas mask erupting out of nowhere” … or… Read more »

George Lucas makes tremendous use of this fear as a tool in his Star Wars Saga combined with the old Hollywood tool that the bad guy wears a black hat. Imperial Storm Troopers just the name and we need no more explanation. The very essence of evil is a man dressed in black breathing through a gas mask. So to this very day ‘The Nightmare’ still there just below the surface. To me storm troopers are little different to blitzkrieg in that it is a convergence point of ideas and theories that everyone is kicking around. Then suddenly someone has… Read more »

@jamesevans140 – Wait a minute, Star Wars has a villain in black who breathes through a mask? No way! See, now I know you’re just messing with me. 😀 But dear God, no more STAR WARS! The series is dead! It’s been creatively dead since 1983! The only parts of the franchise that were good after that were some of the EU material, that Disney / Lucasfilm has now decisively nuked out of canon! *weep, sob* I would agree that the ideas of WW1 stormtroopers and early WW2 blitzkrieg have a lot of parallels, at least in broad conceptual strokes… Read more »

I was just as shocked! I thought Star Wars was about a father with breathing problems trying to deal with a wayward son that he had not seen since the boy was born. 😉 I completely agree about what is being done with Star Wars. I thought there were laws about interfering with a corpse? I also get the patronising comments from my grandson about that was my Star Wars and this is his Star Wars. The realistic depth of penetration to which blitzkrieg could operate at is far greater than that of Hutier tactics. There is a limit to… Read more »

“Your” Star Wars and “my” Star Wars. I would agree with that. “Our” Star Wars is great, “theirs” is terrible. 😮