Gaming In The Vietnam War – 50th Anniversary Of The Tet Offensive: Part Five

February 19, 2018 by oriskany

Here we are at last, Beasts of War, for the conclusion of our 50th Anniversary article series on the Vietnam War’s Tet Offensive.

Read The Gaming In Vietnam Series Here

So far we’ve seen:

- Part One: Introduction

- Part Two: Southern Battles near Saigon

- Part Three: Northern battles near the DMZ

- Part Four: Beginning of the Counterattack

But now it’s time to wrap up the Tet Offensive and review how its uncertain outcome wound up so dramatically changing the Vietnam War (and modern war in general). We’ll also hear from BoW community member Dave Wheeler (@davebpg) for a specific look at wargaming Vietnam in Flames of War: Tour of Duty.

Prognosis: Tet Offensive

Military Failure, Strategic Success?

So we’ve seen how the Tet Offensive attained nearly complete surprise. The NVA and especially the Viet Cong overran targets all across South Vietnam, but in the end were unable to hold any of them in the face of American firepower, or coordinate a successful “Phase Two” of their offensive.

In all, some 80,000 Viet Cong and NVA troops were committed to the Tet Offensive. At least 30,000 were killed or captured, making this a shattering military defeat, especially for the Viet Cong. In fact, the communist political structure in South Vietnam would never be the same, leaving the NVA to lead their war effort from now on.

Strategically, the Tet Offensive also failed because the anticipated popular uprising never took place. The Saigon government never fell. Communist forces had taken punishing damage and did not control anymore of South Vietnam’s geography or population than they had before.

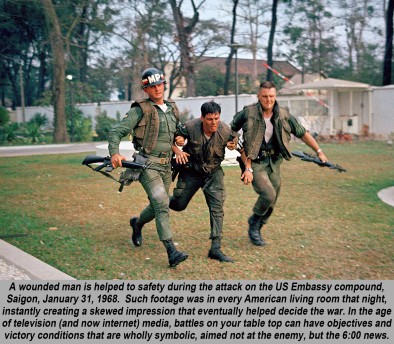

Yet the Tet Offensive had a huge unintended strategic effect, one that demands study by anyone with even a passing interest in how modern warfare is actually fought (or decided). In the end, the battlefield that really counted in Vietnam wasn’t in the hills or the rice paddies or the streets or the jungles…it was on the TV screen.

In a time when live colour footage could be beamed directly into the minds of a democratic population, how a war looks is often more important than the actual battlefield situation. As vital as this point was in the television-dominated 1960s, its relevance in today’s internet age is perhaps even more prominent.

Up until Tet, the American public had been assured over and again, by both military commanders and civilian leaders, that they were winning the war in Vietnam. The enemy was being ground down by attrition, all that was needed was faith, trust, and patience to carry the American military to yet another victorious war.

Tet showed how wrong they were, and that the communists could strike anywhere. The Embassy itself was attacked, the ambassador roused from his bed by Viet Cong gunfire. As President Johnson himself lamented...

“Light at the end of the tunnel? We don't even have a tunnel! We don't know where the tunnel is!”

In the end, the argument can be made that the Tet Offensive, despite its immediate failure, convinced the American public that the Vietnam War could not be won. Militarily this wasn’t true, but Mr and Mrs John Q. Taxpayer had made up their minds. The American withdrawal from Vietnam was now only a matter of time and losses.

Vietnam In Flames Of War

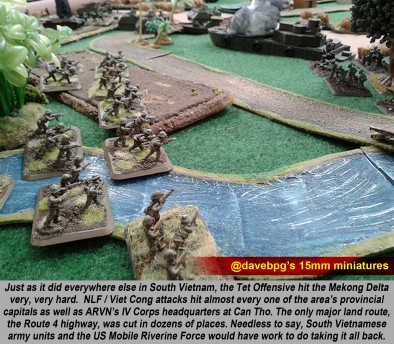

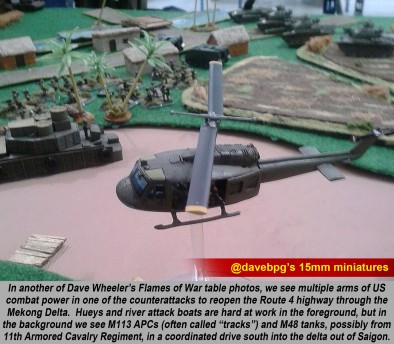

by Dave Wheeler (@davebpg)

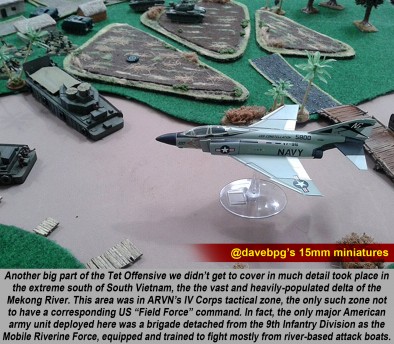

At the moment, Flames of War: Vietnam (FOWNAM) is in a state of flux. The original rulebook was published in 2011 (there was a starter book covering the battle of Ia Drang released with Wargames illustrated in 2009) with a follow-up expansion called Brown Water Navy (detailing the river battles in the south of the country) published in 2015.

There is, however, a new rulebook, being published in conjunction with Osprey, scheduled I believe for some time in 2018 which will bring the ‘Nam rules more into line with those used in Team Yankee and 4th edition Flames of War.

I’m expecting the new ‘Nam book to supersede some of the rules from the first book which I will discuss here.

The recent Team Yankee release, Stripes, has given us an insight into how Battlefront might alter the rules for transport helicopters in the new ‘Nam book so I will try to take this into account and not get bogged down into specifics which could be rendered irrelevant as soon as the new book comes out.

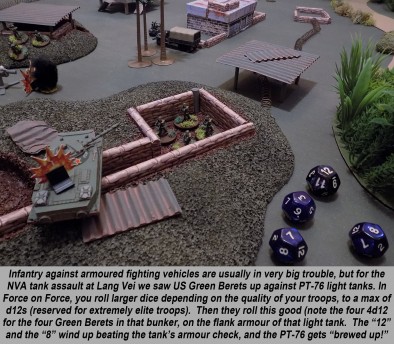

FOWNAM, in my opinion, does a very good job of representing the battlefield conditions the soldiers of both factions would have faced in Vietnam.

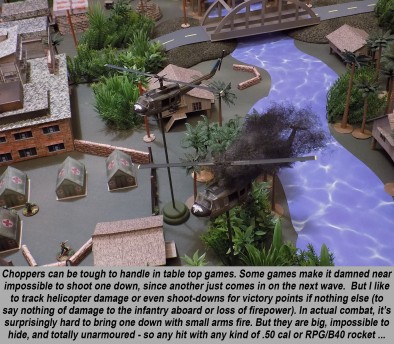

Transport helicopters, for example, are represented very well. For a start, it is impossible to buy (when list building) enough Huey’s to move all your infantry onto the table in one turn, instead they come on in waves and are deployed when and where the Allied player likes.

This holds true to real life as Huey transports where often in short supply, especially once battle damage and pilot casualties started to add up, so having to secure your LZ with your first “wave” of infantry to protect later transports is pretty accurate.

Gunships (Cobras and Huey variants) are even scarcer and are represented by the equivalent points cost. FOWNAM allows you to buy gunships as “Red Teams” and accompanying OH-6 (Loach) scout helicopters as “White Teams”, or you can mix them to make “Pink Teams” (another historically accurate point).

Loaches are able to act as spotters for the gunships whose rockets (treated as a sort of artillery in FOWNAM) can pound the enemy from a distance. With Loach pilots sometimes clipping the tops of trees with their rotors in order to accurately distinct enemy from friendly troops, you can imagine how dangerously vulnerable to ground fire they were.

In fact, I strongly recommend “Low-Level Hell” by Hugh Mills. Not just an excellent book on the subject, but a very compelling and exciting read as well.

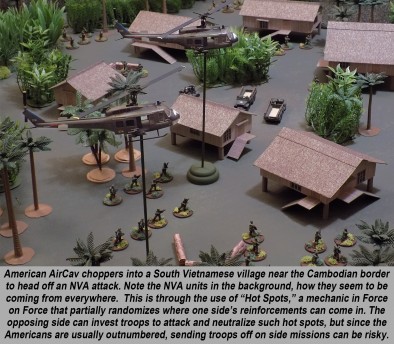

The Allies don’t get to own the table however. The NVA and Viet Cong almost always use various hidden deployment methods, mostly consisting of tunnels. These allow NVA and VC units to deploy literally anywhere on the table that is not within a certain distance of an allied infantry unit.

Loaches acting as scouts can force the enemy to deploy further away but unprotected gunships are very vulnerable. This means it’s very easy for the NVA to encircle and pressure objectives, LZs, and allied infantry very easily. In effect, the NVA and VC “own the jungle” which is backed up by plenty of personal accounts on the subject.

The VC get all sorts of interesting rules to represent their guerrilla warfare style. As well as booby traps (punji sticks, claymores, machine gun bunkers etc.), they can also disguise themselves as civilians. Whilst in civilian disguise, they cannot be targeted, but nearby allied infantry can “question” the civilians to determine their true identity.

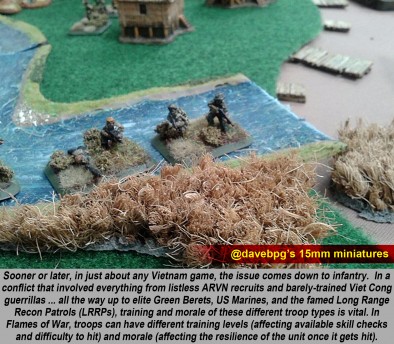

I’ve made reference a few times to the “Allies” in this writing, as Oriskany has pointed out there were troops in action here from many nations besides the United States. South Koreans and ANZACs (troops from Australia and New Zealand) also took part, as well as Taiwan, Laos, the Philippines, and of course South Vietnam itself.

Accordingly, FOWNAM allows you to build armies not only from the US (including armoured, air cavalry and riverine forces) but also ARVN (South Vietnamese) and ANZAC forces.

FOWNAM also has two rules sets presently not found in other FOW books, an absence which has long puzzled me. The first is the ability to keep artillery off the table. This makes perfect sense. Obviously, with the airmobile tactics of Vietnam, it would be daft to set up the artillery on the board before the infantry have even landed.

Besides, artillery nearly always operated from fixed firebases anyway. So unless the firebase itself was under attack, you’d never need put them on the table.

Instead, infantry stands above a certain rank (presumably with a radioman) can spot and call in the artillery. Why these rules haven’t found their way into regular Flames of War and especially Team Yankee is a mystery to me.

The other rule is the medevac choppers and medics that accompany the allied armies. In all honesty, they don’t make a huge difference. Wounded infantry must fall back until they meet up with a medic or medevac chopper. Once they do they roll to see if they are either okay to fight on or wounded badly enough to head back to base.

From my experience, this is rarely a game changer. It doesn’t make allied armies overpowered due to the effective “invulnerability” that a medic might offer. BUT…such enforced “casualty management” does create a fantastic narrative point to every game.

Securing your LZ to evacuate the wounded becomes such a distraction for the allied player that at times you completely forget to do important things like taking objectives, calling in air strikes etc. I suppose the screams of the wounded from your little metal and plastic figures gets too much for you!

And this leads me nicely onto the main reason why I like gaming in the jungles of ‘Nam. Every game turns into a movie, especially if you have the Rolling Stones or Credence Clear Water Revival playing in the background.

One of my favourite moments was towards the end of a game. Most of my US infantry had already left the board, leaving behind one badly mauled platoon to hold the LZ waiting for final extraction. As the Hueys tried to land under a hail of AA fire, one was chased off which didn’t leave enough room to evacuate all the infantry in one go.

With the LT wounded, the sergeant took over and ordered everyone else out, he would get the next chopper. The Hueys took off and circled overhead providing cover fire as long as possible but once the iPod shuffled from “Paint It Black” to “Adagio For Strings”…we knew it was all over.

“There are no veterans’ clubs for this war, no unit reunions, no pictures on the walls. For those who haven’t been there, or are too old to go, it’s as if it doesn’t count. For those who’ve been there, and managed to get out, it’s like it never happened. Only the eighteen, nineteen, and twenty-year-olds have to worry. And since no one listens to them, it doesn’t matter.”

Conclusions

Oriskany Wraps It Up

This concludes our look at the Tet Offensive, the bloody nation-wide assault that not only changed the course of the Vietnam War but also perhaps the way wars are fought (or at least decided) overall. They say “perception matters more than reality,” and at least within military circles, the Tet Offensive is a prime example.

Some historians call the Tet Offensive a success. I disagree. The communists failed to spark a popular uprising in South Vietnam or collapse the Saigon government, which were their stated aims. However, they inflicted massive psychological damage in a different arena, which eventually won them the war anyway (over four years later).

As always, I’d like to thank everyone at Beasts of War; firstly Ben, Tom, and Az for helping get this article series published, and Lance for the great front panel and magazine layout work. I’d also like to thank Warren and Justin for the great interviews, and of course the whole team for letting me publish on the site.

Most of all I’d like to thank the community for their continuing support!

Thanks a thousand times for taking the time to read these articles, and of course for the great comments, questions, and input in the thread below!

"In a time when live colour footage could be beamed directly into the minds of a democratic population, how a war looks is often more important than the actual battlefield situation..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"With the LT wounded, the sergeant took over and ordered everyone else out, he would get the next chopper..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Superb series. Thoroughly enjoyable read. Well done.

Thanks very much for kicking us off, @c0cky30 – and thanks very much for the kind words, especially coming from someone who’s produced some great Vietnam wargaming content yourself! 😀

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/my-chain-of-command-vietnam-war-blog/

Wow an amazing end to an amazing series well done.

One of the big appeals to me is that I can essentially “Play the Movie” to get into the era then move on to more historical stuff once I’m comfortable in the period. Basically the same way I got into Force on Firce by playing the “Day of the Rangers” Book and using Blackhawk Down as a reference before moving on to Russians in Afghanistan.

The Flames of War stuff looks very cool and I especially like the waves of Helicopters. Do I rush the objective or get numbers on the table. Do I rush the LZ or fort up while my opponent gets his stuff on the board. Very cool.

Fantastic series

I haven’t read it yet so no spoilers about who won please

Who won the war? Okay, we’ll be quiet. Who won the Tet Offensive? It’s fifty years on and people are still arguing, so apparently the issue still isn’t decided. 😀

The Media won and lost the war look at the power they have now they bug peoples phones n make storylines up to the point its different to know what’s true.

I don’t know about the media bugging people’s phones, but there’s no doubt that today’s media companies (i.e., internet companies) are mining, storing, and selling our personal and browsing data.

And there’s no doubt that the new environment of algorithm-driven internet media has contributed dangerously to the “echo chamber” culture we now live in. With people increasingly reliant on outlets like Facebook and Twitter for news and opinion, and with trend and news feeds keyed only to provide you with what you’ve “liked” in the past, all you’re hearing are opinions with which you’re already in agreement.

Soon there is no “other side” to a given issue, and anyone who holds a differing opinion is “fake news” or just crazy. No discussion, no discourse, only increasing polarization in media, news, culture, an politics.

Back in October 2015, we went over the impact that companies like Facebook and “VK” (Russia’s version of Facebook” influenced the recruiting, force structure, logistics, international perception, foreign policy (of certain nations) and perhaps even the outcome of the 2014-15 Ukraine War.

The influence of classic “big media” was bad enough in the 1960s. The power wielded by social media nowadays is just terrifying. At least “big media” had the FCC or other national oversight agencies and some laws built around it. Social Media has grown so fast that the world’s national legislative bodies haven’t had time to build a framework around it, and it’s practically ungoverned at this point.

Yes it was a big story last year with the Sun newspaper that is still going through the courts

its Scarry how much they are changing opinions good and bad depending on how they cover story’s today @oriskany

Like Orwell wrote in 1984: “He who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”

We’re just slingin’ out the quotes today, aren’t we?

Well that very true but they went way to far one of the phones they cracked was a missing kid so because they were going in to see messages the police kept searching thinking she was still alive & I don’t think they have the killer now? @oriskany

I’m not familiar with the case, @zorg . 😀

It was the News of the World Milly Bowler case got to see they got someone I’ll not put the link it a bit Gorey.

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/news-of-the-world-closed-six-years-ago-amid-phone-hacking-scandal-but-where-is-everyone-now_uk_595e1f52e4b0615b9e8f5b7a

Inspiring as ever!

Thank you very much for the series @oriskany & co.

I’m gonna miss my weekly dose of jungle warfare.. 😉

Thanks very much, @suetoniuspaullinus ! I’ve really liked the Vietnam figures you’ve been putting up over on the WAYPAN thread! 😀

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/painting/forum/topic/what-are-you-painting-now-2018-waypn/?topic_page=27#post-227543

Another excellent series, very informative. Can’t wait for the next one to brighten up my Mondays.

Thanks very much, @gremlin – happy to say the next one is already started. A little bit of a smaller topic, but hopefully still interesting. We’re also hopefully working on some Great War material to commemorate the 100th Anniversary of the 1918 campaigns that closed the conflict, and also a certain very, very big tank battle in *cough* July *ahem* – sort of a 75th Anniversary thing? (*shhhh). 😀

Great Wrap Up! This leaves us with the importance of TET and @davepbg ‘s section has made me curious to see what changes we will find in FOWNAM.

Thanks, @gladesrunner – from what I have read the Nam updates will bring the FoW Vietnam material out of the “v3 era” and into the general Team Yankee rules framework. If it’s anything like the Team Yankee we played at the boot camp, it’ll be awesome! 😀

Thanks you two heroes for the worthy end of this series.

According to what Dave said on the artillery pieces, we´ll never see them on the tabletop with one exception and … hooray … we have a scenario, “attack on a firebase”. I guess operations like this were integral part of the (Tet) offensive actions by NVA and VC.

However, I have two questions left: Mortars do not count as artillery in this respect? What is the biggest artillery piece we would expect to see on the tabletop? Is it anything that doesn´t need to be towed, i. e. all the man-packed stuff?

Finally I came across a ARVN unit that gained merits, the South Vietnamese Special Commando Unit by the name of “Thunder Tiger”. They helped the Green Berets in the jungle fighting in 1968, says the quote. ARVN minis, we´re coming!

Whether something is a military success or not is mainly dependent on how success is defined and on how much of your objective is achieved, and even then it´s difficult. On D-Day I think the British had the objective of landing on the beach, securing it and then move on to Caen and take it. They didn´t take Caen, but they took the beach. Success or not?

I think the Tet offensive was a success for NVA and VC, because it proved Ho-Chi-Minh right when he claimed: “You will kill ten of us, and we will kill one of yours. In the end it will be you who gets tired of it.” NVA and VC are willing to persevere and they will, and the Americans had to take that serious. The communists meant business … although it´s odd to say a communist means “business”. So, success.

Speaking of successes or no successes I think I know what “obhe” is talking about with the next series in his reply to “gremlin”. Hints: The name of the city around which the fighting takes place starts and ends with the same letter. The name of the operation is similar to a certain hobby brand, the name of which has something to do with fortresses on hills. Am I right? Btw, obhe means “our beloved history editor”.

I´m looking forward to the Michaels offensive series.

These force on force rules seem to me quite playable. Pity I can´t get them here in my country (“sigh”). Oh, wrong, I can´t FIND them here. Perseverance, again.

I´m also rather happy the new FoW book for Vietnam is very good, according to an expert. Has Dave also tried to get some of the new miniatures and are they any good? On the pictures of retailers and manufacturers they look good, but there is nothing but the real thing, right?

Again, thank you very much. Have a nice week. Said the geek. 🙂

When if comes specifically to FoW Vietnam questions, @jemmy – I will defer to @davebpg or other experts like Bothi or Andre77 or James123t.

In Force-on-Force, artillery of ANY kind really is always off-board (including mortars) unless they are on as objectives. It’s not so much a question of weapon size as weapon range and indirect fire capability. I’ve had 120mm smoothbore tank guns on M1A2 Abrams battle tanks in Fallujah street battles, but even 60mm mortars (with ranges of 1.5-2 km) would be literally 20+ FoF tables away (3′ table at 1:72 = a board of only 72 yards, x20 boards = 1440 yards, the range of even the smallest infantry support mortars).

In Valor & Victory, you can see COMPANY-level support mortars on the table. This is usually 60mm mortars used by the US and ARVN, and often captured and used by the NVA / VC.

Battalion-level mortars in that game (81mm US, 82mm Soviet / Chinese) would count as “Light Barrages” – and handled as scenario-specific off-board assets.

105mm howitzers and above would be “Heavy Barrages” – again, always off board.

Typically, the term “artillery” does not include mortars – as they are usually thought of as infantry support weapons. Artillery tends to be its own arm, with 75mm or 105mm howitzers and up.

Awesome information on the ARVN Thunder Tiger. I had heard of the Black Panther ranger battalion that did pretty well in Hue. There was also the 37th Ranger Battalion that did pretty well with the Marines in Khe Sanh. There were good ARVN units (the 18th Infantry Division at the Battle of Xuan Loc was really the only unit that stood up to the 1975 “Ho Chi Minh” offensive that would eventually win the war for North Vietnam) – it just seems like they were the exception rather than the rule.

Regarding Caen – I feel that objective was pretty unrealistic. The objective of really any amphibious assault on Day One is really secure a lodgement secure enough to withstand inevitable counterattack and deep enough to bring on additional follow-on reinforcements for D-Day+1 operations. In this sense I would consider all the D-Day Beaches an objective success, with Omaha coming the closest to failure (measured by depth, ability to bring on immediate follow-up forces, and seizure of defensible terrain to break German counterattacks).

“Obhe?” “Oriskany Beasts of War Historical Editor?” – Or is this a re-spelling of Obi as in Obi-Wan? Your intelligence on potential July operations are pretty accurate. 😀 Oh, gotcha. Our Beloved Historical Editor. Nice to be Beloved. 😀 😀 😀

The Great War series is a little up in the air, as I’m really depending on some other community members for collaboration on that one. We are working on it and we are on track, I just hate making iron-clad promises when I’m not responsible for 100% of the work. Michaels Offensive will just be part of it, though. 😀

To my knowledge Force-on-Force is out of print everywhere, because the Ambush Alley / Osprey contract is no longer in place.

However, .pdfs should still be available. That’s where I got mine, and then printed a black and white copy so I could have a physical reference book at the table side.

Great series 🙂

Vietnam and especially the Tet offensive highlight how much impact the politics at the homefront have on war.

As von Clausewitz is supposed to have said : ‘war is the continuation of politics by other means’

I never read it, but thanks to the power of google we have access to this sort of stuff :

https://www.clausewitz.com/readings/OnWar1873/BK1ch01.html

Not easy to read by any means, but like Sun Tzu’s ‘art of war’ it is worth a look.

It is scary and impressive to think that he already knew some of the principles that became reality.

I would agree that von Clausewitz laid out principles and maxims for war in the late 19th and the first half of the 20th Centuries.

The comparison between Clauswitz and Sun Tzu is always an interesting one. Both sort of had a similar view point on the holistic “totality” of war, but applied it very different ways.

Sun Tzu’s most basic precepts (and super-paraphrasing and generalizing here) is – War is just a part of state affairs. For the state to get what it wants, war is just one tool in a broad array of tools, to include diplomacy, economics, cultural influence, espionage, even religion. War is not always the best option, in fact should only be approached as a “last resort” and after very careful consideration.

“Weapons are tools of ill omen.”

“Know your enemy and especially yourself, and in 100 battles you will be ever victorious.”

“Fail to know your enemy and especially yourself, and in 100 battles you will always be in peril.”

A successful general achieves victory, THEN seeks battle. An amateur seeks battle, then seeks victory.

Clausewitz, on the other hand (besides his theories coming 2000 years later), in many wars proposes “Total War.” One of my favorite quotes to demonstrate how “obsolete” Clauswitz thinking has become in modern war (Book One, Chapter One, “The Utmost Use of Force”):

If the wars of civilized people are less cruel and destructive than those of savages, the difference arises from the social condition both of states in themselves and in their relations to each other. Out of this social condition and its relations war arises, and by it war is subjected to conditions, is controlled and modified. But these things do not belong to war itself; they are only given conditions. To introduce into the philosophy of war itself a principle of moderation would be an absurdity.

Okay, bad news, Clausewitz. This no longer holds true in the nuclear age. 🙁 Sun Tzu has thus become “back in fashion” – with his proposals of wars to be initiated only as part of an overall and ONGOING series of coordinated and holistic state initiatives, used only when necessary, for as short a period of time as possible, and minimum use of force. In the Clausewitz model, “state policy” is more or less stopped or at least changed out of all recognition, and this then continued through the “other means” of outright, total, and “pulling any punches is absurd” warfare.

So the ACW, World War I and World War II are definitely “Clausewitzian” wars. Non-kinetic wars of the post-1945 period (including Vietnam) are definitely Sun Tzu. If Vietnam was fought by Clausewitz rules, it would have lasted 45 minutes with 100 mushroom clouds all over North Vietnam. “Done and dusted,” as they say.

Of course, Clausewitz has the advantage in that he actually existed. 😀 Historians still argue whether Sun Tzu was really a person, or a pen-name for a series of writers covering a general period of ancient Chinese history and philosophy. 😀

Anything from that era (= Sun Tzu) has a lot more in common with mythology and less with actual history, but hey … I’m sure people will wonder about those little metal men they find in our houses in a few hundred years 😉

And whether he was a real person or not … there’s no denying that what was written makes sense.

Besides … people have fought wars over words that certain fictional authors are said to have written.

That’s all we ought to say about this, right? anyways …

It’s kind of interesting how real world tactics described by both can be applied to games.

The politics part is best reserved for true high level abstract games (ie :a game like Diplomacy ), but bits and pieces do work even at a skirmish level (knowing your enemy and such)

That’s right, @limburger, I can see it now. Twenty thousand years after the Pandemic Plague wipes us off this spinning blue speck, the Kardishev-II level alien race that finds our bones and ruins will try to unravel what all these tiny metal men were about.

Clearly these figures were meant to represent an idealized perception of their own anatomy, but it’s unclear why they were so small. It’s certain they held great cultural and perhaps even religious importance, carefully attended, decorated, and maintained by an elite class of priests we think were called “gamers,” and reverently housed in shrines called “display cases.” Most interestingly, on special occasions they were put on carefully-staged dioramas galled “gaming tables,” where (we believe) great epics of their past were recreated and retold for future generations, painstakingly moderated by the “gamer” priests who worshiped a mysterious pantheon of small, stone-like gods called “the Dice?” We still don’t know much about these “dice” deities . . .

As far as wars fought over words “written” by fictional authors – yeah, I’m with you. 😀

Political and cultural factors can sometimes filter down to eve a skirmish level game, but they’re usually the kind of thing that factor into victory conditions, etc. The inability of certain units to call in available fire missions on targets in Hue City might be an example. But you’re right, these are usually conditions over which the player has no control but must contend with, rather than factors they can actually influence on this level.

Oh God, Diplomacy. There’s a beast of a game. Diplomacy: Ruining friendships since 1959 . . . 😀

Great read and a fabulous gaming resource once again!!!

……but now, can we please get back in the bush?

The bush is always ready and waiting for you, @raglan . 😀

Thanks, glad you liked the series. Can’t wait to see your finished figures in the support thread!

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/wargaming-in-vietnam-its-time-to-start-your-tour-of-duty/?topic_page=4&num=15#post-227619

A nice finally guys its hard to not have opinions on such a controversial war were the troops got the brown Stinky end of the stick instead of the politician’s for the mess this war was.

Thanks, @zorg – nothing wring with having opinions, so long as they are based on at least some crumb of fact, they’re proposed in a civil manner, and everyone remains willing to hear others out. So far these threads have been exemplary in that regard, more proof that this truly is a great community. 😀

Yes very informative posts with everybody giving new information from their country’s viewpoint.

Now if we could just get someone from Vietnam on here to post some perspective . . . 😀

I know one thing about Vietnam top gear was having a race through the country and they found the tail of a B52 in the middle of one of the town’s they went into. later a field with APC’s Tanks and the like dumped rusting away.

One thing I’ve found pretty surprising in gathering research for this series was all the photographs of memorials and landmarks in Vietnam for these battles. Most of them have old American equipment set up on display, some of it refurbished, some of it intentionally left in its charred, burnt-out, rusting state. Khe Sanh apparently has quite the site with a small museum and lost of equipment on display.

http://hueprivatecars.com/khe-sanh-combat-base-hue-dmz-tour/

The field may have been the museum they went to?

I think the site of the old American air base is now coffee farms. 😀 – with the museum, visitors center, and old tanks / APCs / helicopters all nearby.

This is the episode in Vietnam

https://topgear.oldtvepisodes.com/episode/watch-full-episode-of-top-gear-vietnam-special-series-12-episode-08-s12e08/ @oriskany

This is a pretty funny show, @zorg ! 😀 I like where the three guys are standing in the square at the beginning and all getting the Vietnam movies wrong. Then they think they’re rich, ready to buy Maseratis and Lamborghinis with their 15 million dong, only to find it’s worth about a thousand bucks. And of course the biggest guy winds up with the most ridiculously undersized scooter.

“They will try to do in eight days what the Americans could not do in ten years – get to Hanoi . . . ” Well, the Americans never invaded North Vietnam and never tried to “get to” Hanoi, so I’m afraid these dudes will have to stop riding tiny motorcycles long enough to read a book or two . . .

Just kidding. A funny show, and cheered me up this morning! 😀 : D 😀

Yeah the Guy’s are nuts on the show.

When he’s taking the motorcycle driving test –

“Is he . . . the most ridiculous human being that has ever lived? Or is living now?”

They are funny stunt’s on the show you will have to see the one with the trucks but the stunts got to weard at the end when they got dropped by the BBC

https://topgear.oldtvepisodes.com/episode/watch-full-episode-of-top-gear-series-12-episode-01-s12e01/

I guess all shows “jump the shark” eventually. 😀

Yup

I’m tempted to argue that the troops in any war get the brown stinky end of a stick …

It’s always the young dieing for the beliefs of the ‘old’ guard at home.

Best not to think of this stuff to hard, because in the end it’s just a game to us (and let’s hope that is all it ever will be).

Just a game to us . . .

Absolutely. And since we’re apparently on a quote-fest tonight . . . who can forget the prophetic writings of H.G. Welles who wrote Little Wars in 1913 – one of the world’s first “wargames” – comparing playing wargames against doing it for real “in 1:1 scale” . . .”

And if I might for a moment trumpet ! How much better is this amiable miniature than the Real Thing! Here is a homeopathic remedy for the imaginative strategist.

Here is the premeditation, the thrill, the strain of accumulating victory or disaster — and no smashed nor sanguinary bodies, no shattered fine buildings nor devastated country sides, no petty cruelties, none of that awful universal boredom and embitterment, that tiresome delay or stoppage or embarrassment of every gracious, bold, sweet, and charming thing, that we who are old enough to remember a real modern war know to be the reality of belligerence.

… sad isn’t it, that this was published in 1913 … in light of what would happen less than a year later?

This world is for ample living; we want security and freedom; all of us in every country, except a few dull-witted, energetic bores, want to see the manhood of the world at something better than apeing the little lead toys our children buy in boxes. We

want fine things made for mankind — splendid cities, open ways, more knowledge and power, and more and more and more.

And so I offer my game, for a particular as well as a general end; and let us put this prancing monarch and that silly scare-monger, and these excitable ” patriots,” and those adventurers, and all the practitioners of Welt Politik, into one vast Temple of War, with cork carpets everywhere, and plenty of little trees and little houses to knock down, and cities and fortresses, and unlimited soldiers — tons, cellars-full, — and let them lead their own lives there away from us.

My game is just as good as their game, and saner by reason of its size. Here is War, done down to rational proportions, and yet out of the way of mankind, even as our fathers turned human sacrifices into the eating of little images and symbolic mouthfuls. For my own part, I am prepared. I have nearly five hundred men, more than a score of guns, and I twirl my moustache and hurl defiance eastward from my home in Essex across the narrow seas. Not only eastward. I would conclude this little discourse with one other disconcerting and exasperating sentence for the admirers and practitioners of Big War. I have never yet met in little battle any military gentleman, any major, colonel, general, or eminent commander, who did not presently get into difficulties and confusions among even the elementary rules of the Battle. You have only to play at Little

Wars three or four times to realize just what a blundering thing Great War must be.

Great War is at present, I am convinced, not only the most expensive game in the universe, but it is a game out of all proportion. Not only are the masses of men and material and suffering and inconvenience too monstrously big for reason, but — the available heads we have for it, are too small. That, I think, is the most pacific realization conceivable, and Little War brings you to it as nothing else but Great War can do.

Great read lads

Thanks very much, @rasmus ! 😀

Well done to Jim and all those contributors who helped in this fine series.

I surprised you with my titbit on the Brits early war, but you definitely go me back with the background and details on Tet, Made me realise how little I didn’t know.

As I said in part 1 , I do have memories as a 9 year old of the new coverage of the battle for the Embassy,

Not sure how I ended up gaming Vietnam when I came out of the RAF in 1981, but think it as going to Salute in *3 ans the shiney syndrome , a company called platoon 20 had just released their Anzac figures and I was hooked,

Lots of digging around for out of production Airfix Centurion Tanks, and the soft plastic M48’s , a expensive purchase of decidedly iffy resin M113’s (later replaced by the excellent skytrex 20mm range , Airfix Bronco’s Skyraider and Phantoms plus Hasagawa Hueys.

Originally used a set or Rules with camo cover Gia Miah I. think they were called, but eventually converted a set of Liecester games WW2 rules and converted the Pony Wars system to control the NVA/NLF whilst all the players played Alkies (funnily enough the system developed later got used to run bugs in Starship Troopers and then later almost reversed to to run rebel forces in the Vietnams style Hammer Slammers.

That should be Salute in 1983!

Thanks very much, @bobcockayne ! 😀 Yes, your surprise information on British involvement in 1946 was interesting. In all fairness, though, that was the First Indochina War (French vs. Viet Minh), not the Second Indochina War (“Vietnam War” – US/South Vietnam / allies vs. Viet Cong and NVA).

So my record on Vietnam still stands! 😀 😀 😀

Just kidding of course. 😀

Yeah, I know the feeling on trying to put together the minis for a Vietnam-themed army. I went to Battlefront and everything on the Vietnam page was taken down, I guess they were gearing up for the new “Nam” release. So I had to cobble together stuff from four different companies. My USMC M48A3s are actually Israeli Magachs (okay, “Magachs” are just M48A3s in Israeli markings), etc.

I used to read Hammers’ Slammers. Indeed a huge Vietnam War influence there, down to the rebels wearing “black pajamas.” Want to see how Vietnam will play out on other planets in a sci-fi setting? There it is. 😀

I hear you re: solitaire Vietnam games, where the game itself somehow controls the NVA/VC. There are a lot of games like that out there, I was recently looking at one themed on the Marines at Khe Sanh.

Thanks again for the great comment!

“That should be Salute in 1983!” – gotcha. 😀

Dave Drake was in the Black Horse as an Intelligence operator during Nam , so they were more him writing about his experiences in a fictional setting , but you probably know that, did talk to him via E-mail a few years back. I was writing articles for Miniature Wargames, for the Hammers Slammers game, and was checking with him if he had any problem with me writing unit histories for fictional units in his Universe for a supplement I wanted to to write, but then never got time, for my own unit Mallets Manglers. Came across as a really nice guy.

Awesome! The guy I game with a lot here in Florida, @aras , is a big Hammer’s Slammers fan. I read a couple of the novels back around 1998-2000 (I remember the job I was working at the time).

I never knew there was a game for that, though. I may have to look into this and send a link to my buddy. He’d probably be interested.

Another great Vietnam – Sci Fi crossover was The Forever War – written in the mid-70s by another Vietnam veteran. Won tons of Sci Fi fiction awards, and it also deals extensively with the soldiers trying to adjust back to civilian life after the war.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Forever_War

I like how you created your own unit, Mattlet’s Manglers! Maybe I should try one, Oriskany’s Obliterators! Okay, that was terrible. 🙁

Yup Heres the link

http://www.hammers-slammers.com/the_crucible.htm

John Treadway who now edites Minature Wargames wrote them:

Think they are still in print.

Did a whole pile of original tongue in cheek versions of units mentioned in the books that developed their own life.:

Units such as the El’ Bharmies

East Riding Constabulary (originally that was the only word I could get to rhyme with the original West Riding Yeomanry.

And of course the infamous Rebels of the Conservative Revolutionary Alliance Party

and the Gov Forces of Patriotic Organisation of National Government.

As most members of The Manglers joked they were there ‘To take the CRAP out of the PONG!

Know the Forever War well, and read the follow up book Forever Free.

@bobcockayne – Making up “tongue in cheek” units: Forever ago my brother @amphibiousmonster and I created an alternate history of WW2 for Panzer Leader, where one of the major fronts of WW2 takes place in the continental United States. We had fun coming up with redneck units, hippie units, all kinds of goofy “flying circus” auxiliaries. We mounted an invasion of South Florida once, with some of the landings in Key West, where Federal forces had to overcome the “Heroes of Margaritaville – Irregulars” -etc. 😀

@bobcockayne – re: Forever War – I could have sworn I saw a graphic novel version of it somewhere, but this would have been 25-30 years ago.

hmmm upcoming content…big tank battle in July….75th anniversary…will we be trading in Huey’s and jungle for T34’s and muddy open grasslands? If so, we’re gonna need a bigger table.

Я не знаю, что вы имеете в виду?

Я не знаю, что вы имеете в виду?

Only in the mating season…It was ghastly

Now, now … let’s not give people the wrong idea. 😀

Kurses . You found me out

Ich weiß nicht, was du meinst?

An excellent series. Thank you.

Thanks very much, @stuart20 ! 😀 Glad you liked it.

A truly great end to a slice of a truly difficult subject matter @oriskany. May I say you handled it very well.

Vietnam was truly a case of no winners just some guys lost more than other guys and anyone that it touched was a victim of it, including their families back home. This I think will remain until the Vietnam War is no longer in living memory. It still goes on for me.

So many people have looked to great detail of this war looking for answers that never gave themselves up. I think some of the answers is not in the detail rather in a macro and inclusive view of the whole world at the time were it all went a little bit crazy.

If you remember in the Midway series we talked about what is a turning point and what was its dynamics. We saw there were lesser and greater turning points. Loose a greater one and that is the point were the war was lost. In the greater turning point there is a moment that is created by the confluence of a number of events or happenings that could have started months or years before the moment. These events we try to align for our benefit.

What I have come to believe, and I would be the first to say I am wrong, Tet was a rare and unusual greater turning point. This turning point was more like a self fueling fire storm that simply carried the events and those involved along with it.

Let’s take a look at the would that Tet lived in.

In British military terms it would be called an emergency while today we would call it a police action. A small war, in British terms of limited warfare. They were still writing the book on this one but they had many rules on what you can’t do and not enough rules about what you could do.

Westmoreland leaves the White House with no war aims our exit strategy. This is an action not a war which means you need neither. But what if the action becomes a war?

Over in the Middle East they are using Cease fire warfare. North Vietnam believes it can play this game at higher stakes.

Just about every other day some terrorist group is hijacking a plane to try to further their cause. I can’t remember if it was 1971 or 1972 had 371 hijackings in that year alone.

The US is going through a cultural change that could turn into a powder keg at any moment.

The under 35s for the first time are starting to question things. Some of the not so nice things that the government and military have done are coming to light. Such as experiments that were done on a select group of the population without asking first.

The under 21s mistrust the government and military completely. Anything the Man says are all lies until he is caught out. You have the hippies that want nothing to do with the war and just want to live in their alternate life style. Pass me the joint, man. Then you have the anti war moment with its protests, rallies and occasional riot. You have an anti government movement throughout the universities of the world holding their rallies along with the anti nuke movements holding protests outside military installations ending with the odd riot. The world economy is booming. Especially out here $AU1.00 got you $US 1.20. So the Middle classes have never had it better. Consumerism is at its height. Just it looked like it was falling apart and they were nervous. So we have a strange mix of things happening. New GIs hardly had time to settle in Vietnam when they were approached by car salesmen offering deals that were deducted by installments from their pay, so when they got home from their tour of duty they had a brand new muscle car that they owned waiting for their return.

There’s a lot more but I will stop here.

All this may seem like rambling but these points and those that I did not mention are moving through society creating currents and under toes. From president to the person on the street are being carried along towards major social revolution. We were living in the nano second where an explosion begins. Now how to accelerate this in the US?

We all too often believe the media is there to bring us the facts about current affairs and we call this news. The media industry is there to sell copy and the more sensational it is, the more it is worth. The old English word for news is gossip and the more you dislike someone or something the more you twist it to your personal beliefs before passing it on. The owners of the media had their own anti war agenda and they shaped the gossip to their agenda.

Yet no sooner the Tet Offensive had started the media were creating copy stating the US had suffered a complete defeat and the war was lost. The population back home would believe this as they knew (or chose to believe) the government and military were lying all along. The powder keg had found its spark. The will of the people had been broken.

Yet the military was actually winning. The Tet Offensive was about as close as it got to conventional stand up warfare that the US fights best. Giap knew this too and the North Vietnamese government was handing the war to the US as it was too soon to roll over to conventional warfare as the US held must of the advantages.

So indeed the Tet Offensive give the Wargamer to begin playing Vietnam wargames as it does resemble warfare they are more used to playing. However there is no reducing it low enough to remove politics. If you do then your not doing Nam. Clausewitz does make a comeback here as Nam most definitely was politics by another means.

Truly great article series that I believe handled an extremely complex conflict very well.

Thanks very much, @jamesevans140 – Indeed I would totally agree that that the deeper one dives into the detail of Vietnam, the further one strays from obtaining any meaningful answers. I would say this applies to the historical pursuit of Vietnam as much as the actual conduct of the war at the time. To Summarize, Over-Generalize, and Over-Simplify, (SOGOS – my new acronym which apparently I’ll be needing more and more in these articles 😀 ) – the American leadership got so “stuck into the weeds” winning individual battle sand counting bodies that they didn’t see or understand the larger picture that they were steadily losing the war.

I do remember the Midway discussion of the nature of military / historical turning points, this was my first sentence in my first article, if memory serves. 😀 Applying that to this series, I would completely agree with the great point you make regarding Tet as one of the exceptions to the rule, “true” turning point rather than the usual belated indicator of a trend that was actually already obvious to all but the uninitiated. Again, to “SOGOS” 😀 – Tet turned Vietnam from a “war of reality” which the Americans were winning, albeit painfully and slowly (results of the 1967 operations prove this) to a “war of perception” that the US was doomed to lose, and did it practically overnight.

I would also agree that the military was winning the war on the ground even during and after Tet. In many ways this was exactly the kind of battle the brass was hoping for, a stand-up fight out in the open (relatively speaking) with an enemy that wasn’t vanishing into the brush. NVA and especially NLF/VC losses were positively staggering. But it didn’t matter, because the war was no longer about reality, but perception, thanks to the aforementioned turning point. Giap hated the whole idea of the Tet Offensive from the middle of 67, he knew it was a terrible idea militarily. Tet was the political brainchild of General Tanh in COSVN, and accepted by Party Chairman Le Duan in Hanoi. Giap is often seen as the “architect” because after Tanh’s death in July 67, Giap inherits the plan and responsibility for its execution. He resolved to make the best of it, and does admittedly add his own “spin” to it (especially re: operations in the north near the DMZ) but if it were up to him, Tet might never have happened at all.

I know the spike in passenger liner terrorism you’re talking about – most infamously this would be after the Black September War, where Syria invades Jordan in 1970, and the founding of the Black September splinter group of the PLO/PLA from the remnants of its infrastructure in Jordan. But that’s another whole article there …

The only thing I’m not 100% in agreement on is again, the application of Clausewitz to the Vietnam War. “Continuation of State Policy by other means” is a phrase in my opinion too often misunderstood, and often taken out of context from the rest of his writing. “War is an exercise in violence put to the utmost bounds – to introduce into war the principle of moderation is an absurdity,” etc. So until I see a mushroom cloud over Hanoi, I’m sticking with Sun Tzu on that one. 😀

Then again, Sun Tzu is 100 times more relevant, enlightened, and generally applicable to most military history that Clausewitz anyway.

Glad the Vietnam series is finally complete. And very glad you liked it, seriously. Your support is always immensely appreciated. I was pushing the support thread for a while but I think I’m letting that go to sleep as well at this point (I have more photos of Hue, V&V Vietnam, etc.) – but I’m not going to punish the community anymore. Besides, the next article series is already started! Part 01 submitted and under review by copy editor / content manager! 😀

Great to here that another series is on the way.

I am tidying up some WW1 stuff, I will send you a copy once it is done.

The issue concerning On War is that it should never have been printed. His money chasing wife printed it after his death against his expressed wishes. As such we are missing the most important parts of it.

Most people have no idea on how to read Clausewitz and thus have no idea about what they are saying. The book was written at the height of the age of reason philosophy. The book is on the metaphysics of war, so it is the philosophy of war. Your take the current argument or believe and you take it to its extremes releasing the stupidity of the argument against its reason. By adding your own arguments and reason you slowly build and move the focus to the opposing pole where your conclusions and points dwell. Here in lies the issue. Those final points and conclusions were never written, we did not reach journeys end and have no idea what he was telling us about war. The other issue is that he was not a very good philosopher. His work was looked down upon by the leading philosophers of the day. However he did understand the basics.

Take a look at a number of his statement from the beginning of his book and then look at them towards the end of the book. Throughout the book he will argue a point with excepted reason and then add another clause to it, slowly refining the statement to his point that he will bring across.

At the beginning of the book war is an act of ultimate violence by the state or government against another state or government being total devastation. Ok this is a SOGOS, by the way I love this acronym, but bear with me as I don’t want to drag the book out to find the exact quotation.

By the end of the book this statement has been transformed by inclusion of clauses. War is now a focused application of violence upon a centre of gravity that will break the political will of another government and people to resist your will placed upon them. So we have gone from kill everyone to changing their minds, SOGOS again.

We are missing at least two chapters as far as I can work out. The next chapter will add further clauses to the statements to tune them to his conclusion. In the final chapter he would have laid out in point and case his conclusions of what On War is. At this stage we step out into the sunlight and marvel at his enlightenment. So it is all about convincing you that you have come to the same conclusion as he and that you are happy that you did.

So to me philosophy of this period is more like pulling teeth. Today I make my case and you would either accept or reject it. So today we would print the last chapter and address the main opposing points and leave it at that. So it would be a work of about 40 to 50 pages.

Today we are taken in as it seems to be a finished work. His wife edited the work to give this impression. So people quote from any part of the work like quoting from the bible.

Sun Tzu had gone in another direction. My 1970’s copy of his work has very large text and is 99 pages. Current copies using small text are 200 pages or more in lengthy. China had a number of writers on war plus or minus two centuries of Sun Tzu that have been included as his work. While the up to the minute copies are now telling you what he had written and how you must interpret it.

De Jomini on the other hand is a finished work that is more hands on practice and as such is reaching the end of its usefulness. There are still many useful lessons. As a section or paragraph becomes obsolete it is marked as such or deleted altogether.

When comparing Clausewitz and De Jomini as contemporary works the latter is far more relevant at the time. Clausewitz is the theory of war, while De Jomini is the Idiot’s guide to war. One thing I love about e-books is that I can afford to have a number of versions of these three books.

War is an exercise in violence put to the utmost bounds – to introduce into war the principle of moderation is an absurdity.

Here he is taking war to its extreme limits, a place where none with a conscience can go. This is a slap in the face to wake the reader up for them to say NO we cannot go there, this is not civilised war. He had established extreme left to which he will spend the rest of the book moving us to the right. So your reaction to the statement is as he intended.

As far as the Vietnam series is concerned with learning the truth about our behind it I will let the veterans of the war have the final say. A favorite in theatre retort, even if you threatened to shoot one of them would be answered through thousand yard eyes.

It just means nothing, man…

It means nothing.

Have to admit I am completely unfamiliar with De Jomini.

While I would continue to hold up Sun Tzu over Clausewitz 😀 I would certainly never propose to toss Clausewitz out the window completely – even if “history has passed him by” to a certain degree in the age of (by necessity) non-kinetic warfare, at least among first- and second-rate powers. There are still sections and ideas in those writings that certainly hold water.

Nor would I hold up Sun Tzu as some kind of Gospel – his writings on the specifics of the use of flame and how to always deploy your formations a little to the left of where you want them because every man in formation has a tendency to drift behind the shield of the next man … Maybe these don’t hold a lot of weight in modern mechanized combat?

Again, to SOGOS, it seems that Clausewitz proposes that when war comes, state policy undergoes a “continuation by other means,” implying that the original means are paused while the war in in play. The Sun Tzu model proposes as a single channel amidst a holistic and simultaneous portfolio of channels, to include espionage, sedition, diplomacy, economics, cultural assimilation, even religion. It’s all one game that often doesn’t jive with the much more segmented and compartmentalized western style of thought (in general, never mind martial theory).

Sun Tzu also emphasizes that most of the real decisions are made well before the war starts. whether or not to even go to war. In Clausewitz these decisions are taken for granted, dictated by the “state policy.” War is almost never necessary in Sun Tzu, and should be avoided whenever achievement of state aims is possible through employment of some other combination of tools available (“Weapons are tools of ill omen” – “War is of the utmost importance to the survival of the state – it is the ground of death and life, the path to survival or destruction”).

Once the decision to go to war is made, again the battle is won or lost before it starts. “The successful general achieves victory and then seeks battle. The unsuccessful general seeks battle, then hopes for victory.” – “When the thunderclap comes there is no time to cover the ears,” etc.

Intelligence is the most powerful weapon in the Sun Tzu model (despite the “Cliff Notes” crowd believing it is speed) – “Know yourself and know your enemy, and in 100 battles you will be ever-victorious. Go into battle without knowing your enemy or knowing yourself, and in 100 battles you will be always in peril. ” In the age of cyberwarfare and satellite imaging this seems more vital than ever.

I may be paraphrasing here, this is all from addled memory at 1:00 AM. 😀

As far as Sun Tzu’s books continuing to “grow,” there are a hundred and one interpretations, contemporaries who were writing at the same time and theorists who have translated and re-interpreted it endlessly.

Then there’s the question over whether or not Sun Tzu even existed as a singular man, or if he’s some kind of pen name shared by a host of oral historians and philosophers, as many believe Homer actually was.

Very interesting reply @oriskany.

As we all know war exists on several layers within the space time continuum. The international military community also goes through periods where one kind of thing gets their interest over other things. It is very similar to the fads of fashion and no less logical or illogical.

For whatever the reason the Prussian/German military culture has driven much of European war culture since Napoleon. Right up to the late 1890’s De Jomini was their man and Clausewitz was an idiot. Then they dropped De Jomini and purged him from their textbooks. Clausewitz was taken up like a misunderstood relative and embedded as he was suddenly understood. De Jomini is lost to us until around the very late 1980’s when his writings are republished.

Sun Tzu I find more interesting. He is just about everyone’s darling at the moment and his composite is being fashioned to our modern eyes.

At the end of the day it probably does not matter if he is one writer or many. The important thing are the lessons to be gained. Too many place importance on the man and not the lesson and what they find relevant.

Today in education we learn facts and figures and demonstrate in tests that we have developed the logic to apply them. Yet this is a very recent kind of reduction. Previously to this we were educated through stories and we demonstrated that we understood the story’s meaning or moral. An example of this kind of learning that still exists today are some chapters of the bible and the story of the little boy who cried wolf. It does not matter if there was a little boy or that there was a wolf who killed him. What matters is we understand what the story is trying to tell or warn us about.

As junior officers both Clausewitz and De Jomini served on Napoleon’s chief of staff . So their outlooks are based from their experience of a career serving on the Chief of Staff of a number of countries. Both were Swiss. Today we would find this as strange that when a war broke out their were employed like mercenaries to fill the Chief of Staff, national interest and the like. However this was the norm of the day. It would also appear to have been the norm in Sun Tzu’s time as well. However he or they felt with the ruler direct involving them at a much higher level.

So for Clausewitz and De Jomini working as Chiefs of Staff a number of decisions were already made for them and they were conducting the war not the failure of policy that created the war. So in their writings they are influenced by their position and only lightly advise the rulership on how they could conduct the policy. After all they are several levels of social standing than the rulership and they lived in times where one had to be aware of your status and conduct yourself in accordance to one’s position in society.

So their writings are not as holistic as Sun Tzu’s writings. Their writings are focused on the strategical, operational and finally tactical and are light on in other areas. This would include things like training as they are used to using what they are given. Meanwhile Sun Tzu focuses on quality and chain of command.

Sun Tzu’s writings covers from the political to minor tactics, so socially Sun Tzu was in a social position where he could write strongly about policy and quality to the rulership. All three have more insight in one area than another, so it would be advisable to use each where applicable rather than use one over another. All three have much to teach us as long as long as we interpret each through modern eyes and to make best use of it in modern times.

Technically speaking all of them are obsolete. All wrote under the assumption that only a country can make war. Yet we live in times where groups spread over a number of countries that are not the enemy. To all three this would be insane stupidity. However some from each does transfer to this modern condition.

All three writings are dangerous if misinterpreted. Both Germany in WW1 and Japan in WW2 read that a ruler should not interfere as the military takes control of the running of the country in times of war, thus removing the options that politics and policy can provide.

The writings of Moa, Kilcullen, Chan and Patel are more relevant to war in our times.

The principals of war that each country builds it’s doctrine upon already contain the shared key points of the writers.

However that fab thing effected the US from Vietnam to the 90’s concerning intelligence. The fad was to use satellites and aerial photography for this. However in the first Gulf War they discovered this was a poor substitute for having a spy in the government or court that spoke to the military. Yes the US had the CIA but it did not report needed information automatically and they were to busy playing with international policy and the KGB to have boots on the ground where needed in Iran.

All thing is just my own thoughts on the matter and as usual I don’t necessarily agree with the flow. But hay that’s me. 😉

If you want a book @oriskany that contains all their writings and compare them try this one.

https://www.amazon.com/gp/aw/d/B007F3D9YY/ref=mp_s_a_1_40?ie=UTF8&qid=1519863169&sr=8-40&pi=AC_SX236_SY340_FMwebp_QL65&keywords=De+Jomini

It is in my E-library.

Cu Chi Tunnels are preserved in two locations:

– Ben Duoc Tunnels (base of Party Committee, Command of Saigon Military Region – Cho Lon – Gia Dinh) in Phu Hiep hamlet, Phu My Hung commune, Cu Chi district, Ho Chi Minh City, publicized by Ministry of Culture and Culture received National Historical and Cultural Relics under Decision No. 54 / VHQD of April 29, 1979.

https://privatecartransferhoian.com/

All too true @oriskany.

A nation-state can hardly afford war now as it is. In the old days it was how many days could the war last before they would have to go nuclear. Today it is how many days can they last before they are bankrupt. Nor can the nation-states get anywhere near the donations either. Hezbollah’s costs for it’s war of 2006 with Israel was mostly funded by international donations.

Are we going the way that only private enterprise can afford war? If so how would the nature of war change?

What would be the plight of the common soldier?

If Lebanese soldier is killed the family gets nothing. In contrast if a Hezbollah soldier gets killed his wife gets a pension and the education of his children is paid for. That is an amazing contrast. Given this how many Hezbollah soldiers are professional soldiers and how many are radicals in the traditional idea of what a terrorist is?

Do we need to create a modern definition to what a professional soldier is and what protection do they have under international law?

I watched a documentary the other week that highlighted how strange times we live in. Many small nation-states in Africa and South America simply cannot afford the cost of infrastructure government departments, yet the country cannot run without them. Most have turned to organised crime to get around this impasse.

If you need to reregister your car or drivers license you go to your local crime boss. He collects the fees and issues any paperwork. He then takes his cut and passes the rest to the government. Even local garage collection is organised this way. Of coarse while your dealing with the local crime boss about these matters you can pickup or organise your illegal drugs and other contraband.

In Lebanon hospitals and libraries tend to be more Hezbollah owned and run. The same goes for basic services such as water, electricity and sewerage.

So what the government cannot afford they are turning to organised crime and terrorist groups to provide.

So sooner rather than later we are going we are going to have to address what all this means. Nation-States are no longer looked up to as an example to follow and they are looking more like things of the past rather than the future.

There is certainly going pressure for the Nation-States to fall apart as well. The Californian economy is something like the 8th largest in the world and is growing. The rest of the US economy is not that good. On the face of it would California and its people be better off without the US dragging it down.

Coming from a culture of imperialism my reply no they would not be. However is this really the correct answer. The world has a long history of civilisations rising up only to collapse into barbarism, of golden and dark ages. There was a glimmer of hope when the British empire collapsed as it gently let go. Empires usually cause the most destruction as they implode.

Do you and I are most definitely living in the most unusual off times.

I am Vietnamese. I am the next generation of this war. I don’t blame this atrocity at all. Because I don’t understand how America thought at that time. And I believe it is also the right choice for your country. But now the two countries are friends. Try to maintain this friendship for the beautiful.

Catching up on this series again after getting the urge to game Vietnam. It’s a truly excellent resource @oriskany *salutes*

Thanks very much, @somegeezer ! Always heartening to know these old article series sometimes still get a look and are useful now and then to fellow wargamers!

I am Vietnamese. I am the next generation of this war. I don’t blame this atrocity at all. Because I don’t understand how America thought at that time. And I believe it is also the right choice for your country. But now the two countries are friends. Try to maintain this friendship for the beautiful.

https://tintuc.hahalolo.com/

Vietnam!