Gaming The American War Of Independence Part Five – The Southern Theatre & Endgame

May 2, 2016 by crew

Alas, all great things must come to an end, and so it is with our American Revolution explorations, presented by @oriskany and @chrisg.

For those late to the party, our previous parts are linked below.

- Part One – The Shot Heard Round the World

- Part Two – Initial Battles & Campaigns

- Part Three – The Central Theatre

- Part Four – War in the North

But for now, let’s close out wargaming retrospective on this amazingly complex and influential conflict.

Under Southern Skies

The Crown’s Perspective

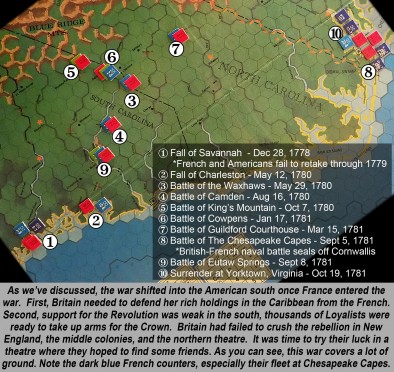

Well, it was only so long before the French entered the war against us. Orders came down to start shifting our efforts down to the southern colonies of Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia. We wanted to be in a better position against the French in the Caribbean, and we were told the colonists in the south would be on our side for a change.

At first, the new strategy seemed to work well. In late 1778, we took the port city of Savannah, Georgia in a seaborne invasion, and won a series of battles as the rebels tried to take it back. Then the French and Americans tried a joint siege to our new city in 1779, a siege which we broke rather handily, I might add.

But the real blow came in 1780, when General Sir Henry Clinton (our commander at Monmouth) mounted an expedition against Charleston, South Carolina. We won again, resulting in the surrender of an entire rebel army, over 5,000 in all, as well as their largest southern city. This would be the largest single American defeat of the war.

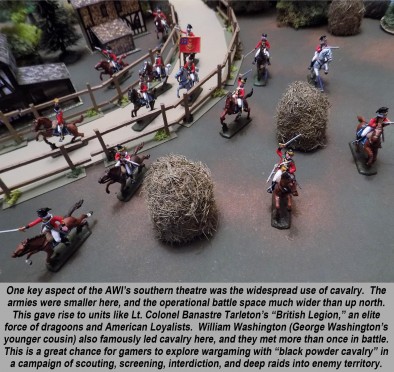

As rebel survivors fled from Charleston, our cavalry raced out after them. One such unit was Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s “British Legion.” These dragoons covered a distance of over 100 miles in 54 hours, and caught up with a column of rebels at a place called Waxhaws. After a brief but ferocious fight, the rebels surrendered.

During the surrender, however, Tarleton’s horse was shot from under him. His men, believing he’d been killed, laid into the rebels with sabre and bayonet. The rebels predictably labelled the incident a “massacre” for propaganda reasons. Nonsense, of course, but I will confess that Tarleton was a commander with no shortage of killing instinct.

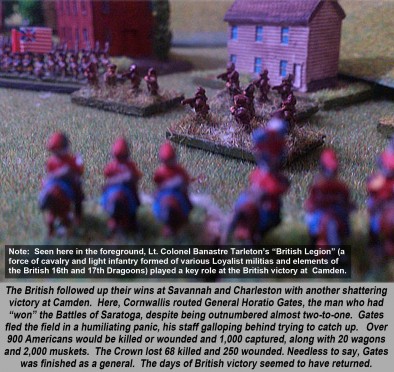

After the fall of Charleston, our General Charles Cornwallis was left in command of the south. He set off into the interior of South Carolina, intent on destroying the rebels under the newly-appointed General Horatio Gates. Their first battle was at Camden (August 16th, 1780), where we completely routed a larger rebel force.

A Brother's War

The Patriot Perspective

What had happened? Weren’t we winning this war? Savannah, Charleston, Waxhaws, Camden, we felt like we were back in New York during that terrible summer of ‘76. Huge numbers of southern Loyalists made things worse, resulting in personal, bitter, and savage fighting between Americans … which was always so much worse.

The British couldn’t usually control these Loyalists, though. Atrocities were horrific, frequent, and committed liberally by both sides. One battle, Kings Mountain (Oct 7th, 1780), was fought almost entirely between opposing American militias. True, it was nice to finally win a battle, but not against our own neighbours and countrymen.

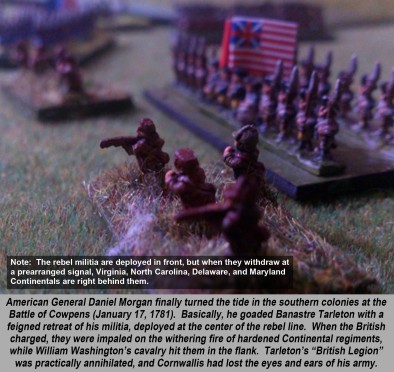

Finally we managed to turn it around. Daniel Morgan, founder of the Virginia Riflemen and hero of Saratoga, finally lured the “Butcher” Tarleton and supporting British units into a Battle at Cowpens, South Carolina (Jan 17th, 1781). We tempted them into a charge with a false retreat, then let them have it with point-blank musketry.

That was the end of the “Tory Legion” as we called them. Cornwallis came after us, of course, but our new general Nathaniel Greene just kept fighting and falling back, fighting and falling back. We lost every battle, but steadily exhausted and wore down the strength of Cornwallis’ Army as we withdrew up into North Carolina.

One such battle was Guildford Courthouse (March 15th, 1781). Again we lost, but not before Cornwallis lost a further quarter of his army and even had to use artillery on his own men. Hundreds of years later, Nathaniel Greene’s defensive campaign in the Carolinas is still seen as a masterpiece of asymmetrical operational warfare.

Yorktown

The Patriot Perspective

For most of 1781, we led Cornwallis and his redcoats around the Carolinas, sometimes literally in circles. Finally, they gave up the chase and instead headed north to Virginia (against the orders of his superior, General Clinton). Here, Cornwallis hoped to cut communication between the northern and southern colonies.

Bad move. Moving that far north allowed Washington to march down against Cornwallis, along with a sizable force of French troops under General de Rochambeau. Before he knew it, Cornwallis was pinned against the coast at a small Virginia town whose name history would never forget … Yorktown.

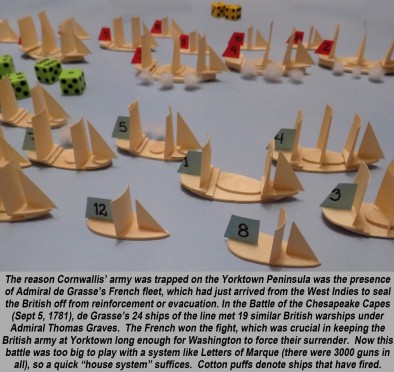

So couldn’t the British just be evacuated by their navy, as they’d been from Boston in early 1776? Not this time, since the French fleet from the West Indies under Admiral de Grasse had come up to blockade the British in. Quite a risk, to sail in the Caribbean at the height of hurricane season with all those wooden ships.

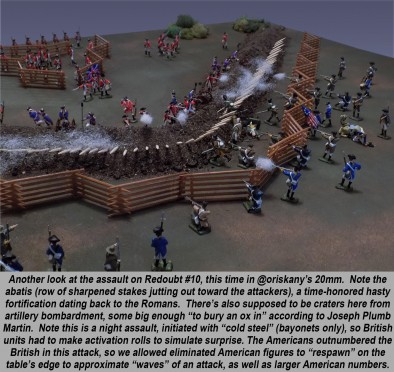

When the French fleet defeated the British at the Battle of the Chesapeake Capes (Sept 5, 1781), Cornwallis’ fate was sealed. Now it was just a matter of bombardment, siege works, and steadily tightening the ring by assaulting outlying fortifications. The most important of these were Redoubts “9” and “10” on the southeast perimeter.

World Turned Upside Down

The Crown Perspective

Outnumbered by the combined French and American forces (almost 20,000 in all), we had no choice but to dig in as best we could and hope for help to arrive from New York. The American and French bombardment was ferocious and incessant.

For three weeks this went on, through the rest of September and into October. But when our enemies assaulted and took two of our outer redoubts (No 9 and 10), our defences were well and truly cracked. Direct-fire American guns could now be brought right up to our inner defences and fired straight into Yorktown itself.

Finally, Cornwallis had to surrender on October 19th, 1781. As our units marched out of Yorktown to lay down their arms, legend has it their bands played a song called “The World Turned Upside Down.” Indeed it had been, how else could the most powerful army on earth be surrendering to a third-rate rebellion?

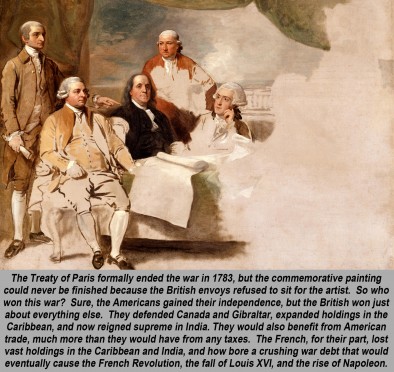

The disaster at Yorktown forced a change in British government. The new Parliament wanted an end to the war in America, so even we fought the French, Spanish, and Dutch around the world, fighting in America came to a close. Against all odds, and despite all the times we SHOULD have won this war, the rebels had somehow prevailed.

A Global Stage

As previously discussed, one of the most dramatic shifts in the American War of Independence was the entry of France into the war on the American side. Immediately this turned the conflict from a colonial, regional issue into a full-scale global war, one that would see furious fighting all around the world.

First, the French and British immediately came to naval blows in the English Channel, bringing the war right to Britain’s doorstep. Intense fighting also erupted as the French struck toward British possessions in the Caribbean like Jamaica, Barbados, and Dominica, islands of immense commercial value that had to be defended.

The British were soon striking back at French possessions in the Caribbean like Guadalupe and Martinique. Given the monetary value of these colonies, it’s easy to see why battles over backwoods American farms were almost forgotten.

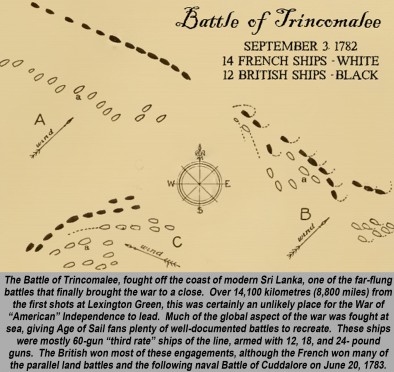

Spain joined the war against Great Britain in 1779. This ignited a fight in the Mediterranean as Spain fought to regain control of Gibraltar, lost to Britain in 1704. France was also trying to usurp British control of India (France held colonies here at the time), sparking naval battles, sieges, and land engagements across India.

Finally, war broke out between Britain and the Netherlands in late 1780, when the Dutch refused to stop smuggling arms to the Americans out of St. Eustatius, another island in the Caribbean. Indeed, this war had come a long way since those first shots on the Lexington Green almost six long years ago.

Even after the fighting in America stopped at Yorktown in October 1781, the rest of the “world war” raged for two more years until the British finally won dominance in India at the naval Battle of Trincomalee in late 1782. The Treaty of Paris, finally ending the war and ceding American independence, wasn’t signed until 1783.

Finally, the war was over.

Conclusions

Thus concludes our journey through the American Revolution. Of course there is plenty more to say, in just five short articles there’s no way we could cover everything. We weren’t able to cover the global aspect of the war in nearly enough detail, to say nothing of the “frontier war” in Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

Perhaps some of you with knowledge in these areas will share some of your knowledge in the comments below?

As always, we would like thank the Beasts of War team, especially Ben and Lance for helping us publish our material on the site - the links, the layouts, the scheduling, and of course for making our articles look so amazing.

Even more so, we’d like to thank all of you for taking time out of your busy gaming day to read through our ramblings. Your time, patience, and merciful eye are all appreciated, almost as much as your comments below! Let us know what you think, or share any experiences you may have had with 18th Century wargaming.

By James Johnson & Chris Goddard

If you would like to write for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"...before he knew it, Cornwallis was pinned against the coast at a small Virginia town whose name history would never forget, Yorktown"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Even after the fighting in America stopped at Yorktown in October 1781, the rest of the “world war” raged for two more years..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

A great end to a fantastic series! 🙂

Thanks very much, @gladesrunner . 😀 Admittedly I had to cram quite a bit into this last one, but hopefully it works out and the readers enjoy it all the same.

Well done @oriskany and @chrisg . I had no idea the French were involved on such a grand scale in the land battles. I thought their contribution was mostly naval. Shows I need to brush up on my history!

The missus has been thinking about getting into AWI, mostly for the models and the beautiful terrain that has recently been released, but I think she might enjoy the gaming aspect as well. Can you recommend any mass combat tabletop systems for this era, one where you could play larger battles like Saratoga… er… Freeman’s Farm?

Thanks for the comment, @cpauls1 . I’m pretty sure that Yorktown was the only really BIG one French ground troops got mixed up in, and even that is more of a “siege” than a “battle.” There may have been some additional small landing engagements up by Rhode Island, I’m going to have to check up on that. As far as mass combat tabletop systems … eh … that’s kinda tough. And it’s part of why I pretty much built my own for this series. Most of the ones I’ve found have been a little too simple or a re-freakin’-diculously detailed… Read more »

As for games with toy soldiers – there is Blackpowder from Warlord Games and the is a AWI book for it as well

I’ve heard good things about Black Powder from Warlord, @rasmus . Is that more of a skirmish-level game, i.e., 1-1 figures / soldier, with about 15-30 soldiers per side?

What I see it is a full on real wargame – I did see a game of the Franco-Prussian war in 10 mm – around 15 regiments aside

Holy crap. Okay, @rasmus – I was thinking of a different game. Maybe the Perry’s 28mm range.

Black Powder is a full regiment game. Although, most of time a single 28mm model is representing 50-100 men. I play the American Revolution through Black Powder since I find the system pretty accessible (read: easy to teach new players). However, the rule book itself can be very confusing if you aren’t familiar with either the era (like I wasn’t) or I believe Warmaster (which I have never even seen played). I like Black Powder well enough. However, it does feel like I am leaving out a good chunk of the rules when playing the American Revolution as the system… Read more »

Gotcha, @clash957 . I was actually kind of wondering what people were talking about, with 20mm and 28mm yet they can still “do the big battles” that included tens of thousands of troops. So these are “command tactical” games, where the representation isn’t 1-1. Sweet. This was exactly what we were looking for. I know what you mean re: the differences between Napoleonics and AWI. People tend to think they are very similar, and in some ways they admittedly are. But there are also noticeable differences. One is the attack column you mention, which I believe was a French tactic… Read more »

Thanks @oriskany I’m looking for something where you’re going to have a lot of models a side, say a 20:1 ratio or thereabouts, so we can play small engagements but can still scale up (and spend thousands in the process) :-).

Would you recommend 20mm soft plastic as the way to go? Seems relatively inexpensive compared to 28mm, but hard as hell to paint.

Oh, @cpauls1 -you’re talking about a miniatures game. Okay, in that case, yeah, the Redcoats and Rebels system seems pretty good, if complex (their suggested conversion scale runs from 20-50 men per miniature). http://freewargamesrules.wikia.com/wiki/Redcoats_and_Rebels I can’t say I’ve tried this game, but actually found it a pretty solid source of research because holy hell, have these guys done their homework. It’s a beefy game, so perhaps a simplified, streamlined version would work. As far as models to paint, I just bought inexpensive soft-plastic “army men” from toysoldiercompany rather than actual “miniatures.” They painted all right, at least if you look… Read more »

I think for hex based games for the AWI you could use not so much modular boards but use terrain pieces on a blank map instead, in the same fashion we use movable terrain pieces on the tabletop.

You know that’s not a bad idea, @jamesevans140 – I never used to give modular hex terrain much of a thought until I saw some of the boards for the Tide of Iron series. Not the best games, overrated, unbalanced, and overpriced, but you can’t argue with the quality of their boards and how precisely the modular hex elements fit over the base board (okay, so maybe not so overpriced). Hell, even the Memoir series was pulling this off with reasonable success. Granted, you’d have to exponentially drop-kick this concept to the stratospheric new heights in order to achieve anything… Read more »

Great stuff once again, love the ping pong between the two of you

Thanks very much, @rasmus . Yeah, when we started we were aware that lots of people on BoW would come down on both sides of this issue, so rather than avoid it, we decided to go straight into it in a light-hearted away.

Thanks very much for the comment! 😀

Here are a few options for AWI miniature games. I’ve not played them all but mentioning them in case anyone wants to look them up. Muskets and Tomahawks is a skirmish game covering both the FIW and AWI. I like it a lot. Black Powder and its Rebellion sourcebook cover larger battles. I’ve not played BP but I do own the rules and they seem decent. Osprey did a rule set called Land of the Free. I don’t know much about the system but it’s a beautiful book. For miniatures I’ve tried the Perry and WGF (now Warlord) lines and… Read more »

Great suggestions, @koraski – Black Powder seems like more of a match for me, but that’s just because I tend to like larger battles.

I have tried Muskets & Tomahawks (as noted in these articles), and it’s a great game if you’re into a more skirmish-based model. A great part of M&T is the “subplot” mechanic if you’re just looking to play a game less “nuts and bolts” reliant on historical detail.

Just saw the great big battle in a box starter on the Warlord site. If you’re affected by shiny things, you may want to stay away 🙂 Terrific deal!

Thanks for the info @koraski 🙂 I’ve gone looking for the WGF models on the Warlord site, but couldn’t find them. Do you have a link?

Never mind. Found it. Hadn’t been on the site for a while… duh.

If WGF stands for “Wargames Founry” – I also found these:

http://www.wargamesfoundry.com/our-ranges/american-war-independence/

😀

The Wargames foundry ones are the last ones the Perrys did before they started Perry Miniatures as far as I remember.

Great series of articles by the way

I think the WGF they were referring to would be the Wargames factory plastics

Thanks very much, @huscarle . 😀

Okay, so according to the August 12 announcement linked below (forgive me if this is old news) – looks like Warlord Games will be the exclusive worldwide distributor of all Wargames Factory miniatures, including their sets for the American War of Independence.

http://www.wargamesfactory.com/announcements/warlord-game-and-wargames-factory-partnership

Yes I meant War Games Factory. As per the link above Warlord picked up most of the ranges. The WW2 stuff is available through Dreamforge now but everything else including unreleased kits are Warlord now.

I always thought Wargames Foundry was WF while War Games Factory was WGF but that naming convention may only exist in my head…

All this reminds me of the time on an old thread we were talking about AWI, and through a typo, I started “talking” about AIW.

So American War of Independence turned into Arab-Israeli Wars.

“Hold on, hold on. Israeli Centurion battle tanks at Yorktown? Okay, we crossed some wires somewhere.” 😀

Loved this series gents, many thanks for putting such an immense effort to cover it for us. As a little bit of added history, it was during the siege of Gib in 1776 that the Royal Engineers was formed (then called the sappers & miners). 300yrs old we are, Hurrah for the CRE!

Thanks, @brucelea – if there was ever a place for ‘little bits of added history’ it’s here. I think @crazyredcoat brought up the Siege of Gibraltar in one of the earlier threads as well, so I’m glad we could give it a mention. Jeez, this siege lasted three years?

Almost as long as it’s going to take you to paint all those Soviet infantry, I’ll bet (just kidding). 😀 😀 😀

Having little knowledge of AWI this has been an interesting and enjoyable articles which have inspired me both look further into the history of this campaign and pick up some AWI mintures. Thank you for a fantastic series of articles.

Thanks very much, @chrisgear84 . If even just a couple of people start looking at the AWI or even run some games set in this part of history, then all the work was worth it. 😀 Glad you liked the series! 😀

Inspired partly by this series and partly by oriskany’s mention of Black Powder, I decided to write up a full review of the Black Powder supplement Rebellion! for the American War of Independence. It can be found in the Historical Gamer Town Square.

Awesome, @clash957 ! Spin-off thread! I love it! I will definitely check it out!

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/black-powder-rebellion-review/

Another excellent series of articles. You have both done an awesome job, so-much-so that Jamie has been on the Warlord website everyday looking at the starter sets and rules. What have you started?

Again, loads of things I never knew on a topic that I have no ‘gaming’ connection to, but enjoyed reading every installment.

Do you recommend any further reading?

Thanks, @unclejimmy . 😀 The two books I recommend (and apologies if I’ve recommended these before) . . . Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier (Short Title). Written by Joseph Plumb Martin, who started his war at Long Island in August 1776, joined the Army at 15 and served all the way to the very last assault on Redoubts 9 and 10 at Yorktown. His is the only complete first-hand account of a man-in-the-ranks through the whole Revolution. Essential for the “what it was like to be really be there” perspective. http://www.amazon.com/Narrative-Revolutionary-Soldier-Adventures-Sufferings/dp/0451531582 Patriot Battles Written by Michael Stephenson. I mention this… Read more »

This has been a great series. A lot of hard work has gone into it. Another rule set

I like the look of is ‘British Grenadier’ by Partizan Press which is an AWI adaption

Of ‘General de Brigade’ rule system which is great for larger scale games. Well worth

checking out.

Thanks, @ozzie – I’ve done some quick checks on this British Grenadier system you mention, and found the link below that shows some pictures of sample pages. Indeed, these books look great. I also see where they revised their “Freeman’s Farm” scenario – nice to see they’re still working on and improving the most important battle (by that I mean my favorite battle. 😀 😀 :D)

https://www.caliverbooks.com/Partizan%20Press/partizan_BG.shtml

Thanks for the comment!

After the dominance of the British in the first four episodes, I just didn’t see the ending of this story coming – America gaining independence, what a plot twist!

In all seriousness though, fantastic series of articles. I’ve learnt a lot about this period of history, dispelled some myths I had about the war and learnt the relevance of ‘oriskany’. Well done and many thanks – what’s your next series of articles going to be about….?

Thanks very much, @redvers . What makes this final act of the AWI even more of a plot twist is the fact that even now, the British were dominating the war almost up to the very end with tremendous victories like Savannah, Charleston, Camden, Waxhaus, etc. Sometimes it feels like the AWI is “fictional,” a Hollywood script written by studio executives where the scrappy underdogs pull it out only at the last minute. Of course, the reality isn’t quite that cartoonish. The Americans suddenly got some very powerful friends — British attention, effort (and victories) were suddenly diverted in ten… Read more »

a great read guys nice one @oriskany & @chrisg

Thanks very much, @ zorg ! 🙂

Jamie has just bought a copy of ‘Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier’ and a rulebook for AWI. How long before he buys that starter set?

Hopefully not too long, @unclejimmy ! Liberty or Death! One of the thing I like best about Narrative of a Revolutionary solider are the little bits of nostalgic “military antics” he gets into. They sneak out of camp some nights looking for what they call a “wee sip of the good creature.” Someone in his company gets in a fistfight, and his mates try putting him in the back of morning formation so the Lieutenant doesn’t see the black eye he’s sporting. All the same bulls*** we used to pull in 1989-93, you probably pulled in your day, they probably… Read more »

First off…it blows this got bumped of the front page. We see so little history on the site it’s a shame to have to hunt for it. Anyway, I realized I never commented on the ship models. I mean you can tell they are very basic, but they get the job done, they can be easily differentiated by class, and they are a new thing to see on a Revolutionary War board. I also love how the redoubt turned out in the photos with their anti-personnel spikes. (Though the dirt on the dining room table was a bit in a… Read more »

In all fairness, 😀 😀 this last article did hit in the middle of Dark Ages week, and they left the article up on the feature bar (top of the front page) for an extra day. And you can always use the tags (Historical / Content: Article) pull all of these up.

And hey! I cleaned up all that dirt! 😀 Very very little of it ever wound up on the floor. 😀 Trust me, I spent way too much time picking little roots and pebbles out of it to let it go waste!

Thanks guys @oriskany and @chrisg !

It was a very interesting journey into the American Revolution 😉

I must admit that I am really intrigued by the mechanism which led to the British defeat. Wonder how it would end if Cornwalis did listen to his superior!

Thanks very much , @yavasa – and really great question. If Cornwallis had “done as he was told” by General Clinton and come back to New York earlier, obviously Yorktown never happens. So I guess this really comes down to what would happen if the war had extended into 1782 … 1) Obviously, Washington, Rochambeau, and de Grasse never would have cornered him at Yorktown. That defeat would never have happened, and the British Parliament wouldn’t have called for the British Prime Minister to be replaced (the fall of the Frederick North government) and replaced with one who were tired… Read more »

Thought something similar @oriskany but you made hell of an interpretation! 🙂

Yeah, @yavasa – once I get typing I tend to get carried away. Sorry about that. Especially when I have the day off from work. Four day weekend! Whoo-hoo! 😀

Thanks.

So we come to the turning of the last page of another great series. First of all congratulations to @chrisg and @oriskany for a great and seamless collaboration on this article series. What I enjoyed most was the use of multiple scales on the hex map and table. These scales you guys showed us from the grand strategic to minor tactics that have an extremely clear and inspiring view of the AWI. You guys have shown me this tiny little side show growing into a world conflict that will see major changes and sadly almost lost in the detail a… Read more »

Thanks, @jamesevans140 . 😀 In regards to the multiple levels – we knew that we wanted to talk about (and people would ask about) the higher-level operational and strategic questions, so I wanted to use / include a game that would at least attempt to portray that level. Also, trying to talk meaningfully about the tactical details of battles is difficult without first establishing a wider context. A picture is worth a thousand words, which means “wide-angle” operational maps. Having big game map photos is (a) more “appealing” since it brings a further gaming element to the audience, and also… Read more »

Yet again you have failed! Failed to disappoint me again. An Excellent finale to an excellent series. Thanks to you both.

Thanks very much, @hengest . 😀 when you come to the end of project like this, you’re always half-relieved it’s finally finished, but half-sad too.

That’s why there’s always “the next project.” 😀