The Saratoga Campaign Of The American Revolution – Part Three: Burgoyne Runs Into Trouble

September 28, 2017 by oriskany

We’re back, Beasts of War, for our continuing series highlighting the 240th Anniversary of the Saratoga Campaign of the American Revolution. Fought between the forces of the British Crown and Patriot rebels in the summer and fall of 1777, it would turn the tide of the war and is thus directly instrumental to the founding of the United States.

Thus far we’ve outlined the campaign’s background in Part One, as well as presented a 20mm wargame recreating the Battle of Hubbardton. In Part Two we looked at a supporting British drive from the west meant to support the Crown’s main invasion of New York State. This, of course, led us to a wargame recreating the Battle of Oriskany.

So let’s get stuck back in, and see where the Saratoga Campaign goes from here.

“This Was Going So Well”

Burgoyne Assesses His Options

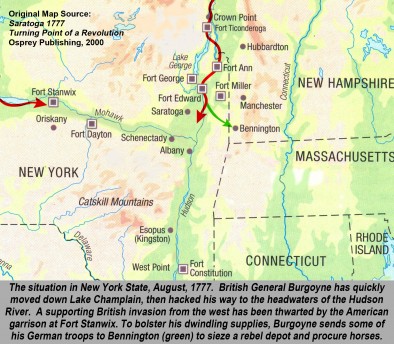

Just to quickly recap, the British commander of this invasion was General Johnny “Gentleman” Burgoyne. His overall plan was to advance from Canada down into upper New York State. By seizing the line of Lake Champlain and the Hudson River, he hoped to split off the “core” of the rebellion in New England and win the war for Great Britain.

To execute this plan, he gathered an army of some 10,000 British regulars, Crown Germans from Hesse-Hanau and Brunswick, Canadian Rangers, American Loyalists and Iroquois warriors. Initially “Gentleman Johnny’s” plan was going smoothly, taking Fort Ticonderoga almost without a shot fired and winning the Battle of Hubbardton.

As July gave way to August, however, the British started to run into problems. A smaller supporting invasion from the west had broken down completely, stalemated by an American garrison at Fort Stanwix and the bloodbath that was the Battle of Oriskany.

So although he didn’t know it yet, Burgoyne had lost his supporting invasion from the west (expected to meet him in Albany, capital of New York). More bad news arrived from British-occupied New York City, where another planned invasion had been postponed. Of three original participating armies, only one remained. Burgoyne was on his own.

Burgoyne’s main body had also entered much, much more difficult terrain. His problem was that Lake Champlain and the headwaters of the Hudson don’t quite touch, and the few dozen miles between them are mountainous, cut by steep ravines, and impassably wooded.

The American commander, Major-General Phillip Schuyler, heavily outnumbered, tried to make the most of this tough terrain. American woodsmen and militia fanned out through the woods, cutting down trees along the precious few hunting trails and wagon tracks Burgoyne might use as “roads.”

Canadian woodsmen were sent to clear this damage and build small bridges over (not kidding here) up to fifty separate ravines. But Burgoyne’s army had to chop and hack their way through the sweltering summer heat, endless trees, clouds of mosquitoes, and struggle across repeated ravines and rocky brooks.

So difficult was this terrain, in fact, that while Burgoyne had “blitzkrieg-ed” his way down 132 miles of Lake Champlain in no time, but it took him twenty-one days to advance the twenty-three miles from the southern tip of Lake Champlain to Fort Anne.

Burgoyne bears plenty of blame for this. As much as he bemoaned his tenuous wilderness supply lines and his slow advance, his army carried with him a huge convoy of champagne, fine uniforms, musical instruments, furniture, crystal, everything needed to party in the rarefied style to which a gentleman of note might be accustomed.

Burgoyne was also enjoying a vivacious affair with the wife of one of one of his commissary officers, and the two would stay up half the night drinking, singing, composing songs, all while his army marched ever deeper into the jaws of very serious trouble.

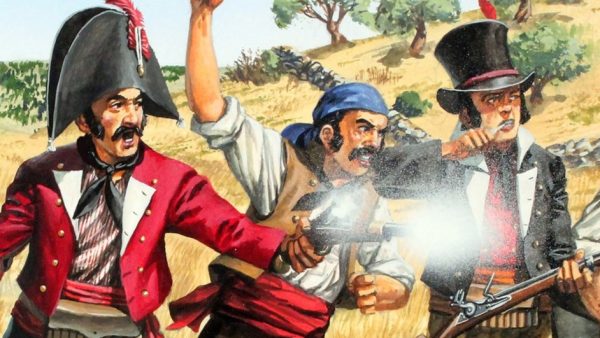

Burgoyne then made a disastrous error. Determined to intimidate the local populace into joining his Loyalist ranks rather than growing Patriot militias, he issued a proclamation in which he outright threatened to “give stretch to the Indians” and release his Iroquois warriors on any local farms or towns not signing up to Burgoyne’s cause.

This led to a controversial incident in which a locally famous woman, Jane McCrae, was murdered and scalped, the top of her skull and long red hair presented triumphantly to Burgoyne. Burgoyne was disgusted, but the damage had been done. The news spread like wildfire and soon American generals were drowning in enraged Patriot volunteers.

As Burgoyne finally reached the headwaters of the Hudson, skirmishing heated up along his route of advance. He was able to set up bases of supply at places like Fort George and Fort Anne, but the extended length of time it had taken him to get here meant that he had practically no supplies left to put in these forts.

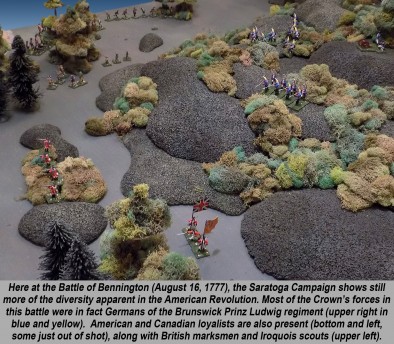

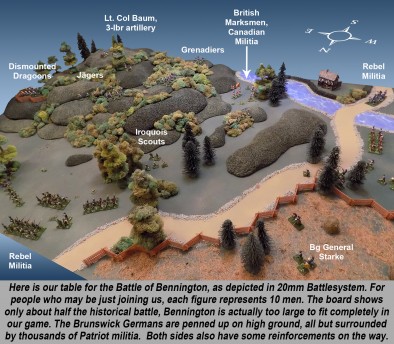

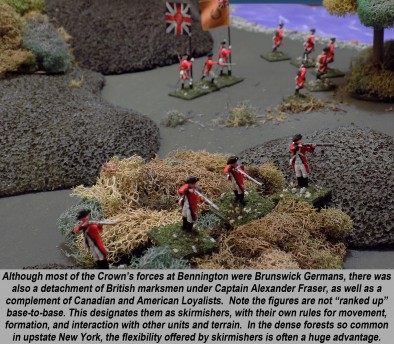

This sharpening need for supplies, horses for his German dragoons, and Loyalist reinforcements prompted Burgoyne to send Lt. Colonel Friedrich Baum, one of his Brunswick officers, to lead a force of 800 Crown Germans, British marksmen, and Iroquois scouts eastward to capture a rumoured depot of American supplies, horses, and carts.

Unfortunately for Baum, he and his column would run into a Patriot militia force almost three times their size at the Battle of Bennington. Burgoyne was about to suffer the next hobbling setback in his planned invasion down the Hudson River.

The Battle Of Bennington

August 16th, 1777

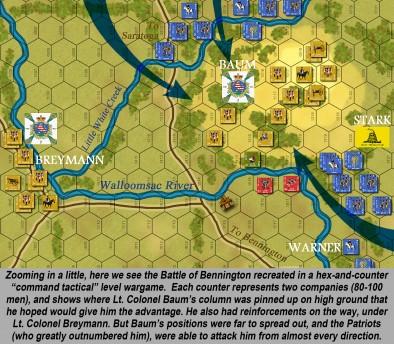

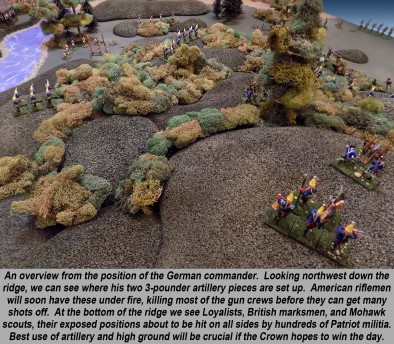

Lt. Colonel Baum led his force (mostly dismounted dragoon cavalrymen of the Prinz Ludwig Regiment) eastward toward Bennington. They skirmished with American militia along the way, and by August 14th were in no doubt that a very large American force stood in their way.

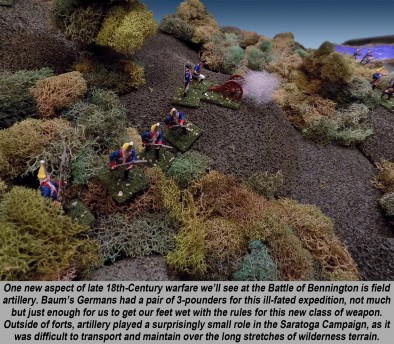

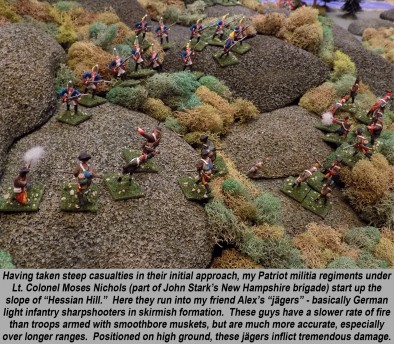

Still, Lt. Col Baum wasn’t too worried. American militia had a habit of fleeing the battlefield practically at the first sound of gunfire. Also, as the Crown forces reached the main bulk of the American militia force, Baum fortified his position (including three-pounder artillery support) atop a tall hill overlooking the Walloomsac River.

The American commander was Brigadier-General John Stark, a rough, surly, and combat-hardened New Hampshire veteran of Bunker Hill, the 1775 Invasion of Canada, Trenton, and Princeton, as well as the French and Indian War. As a colonel, he’d quit the Continental Army when less experienced officers were promoted ahead of him.

Now Stark was back, coaxed back into service by promotion to brigadier-general. Stark had accepted, but only on the condition that his New Hampshire militia would be independent of Continental Army command. Many of his “militia” were also former Continental regulars, and so would not “run from the first shot” as militia often did.

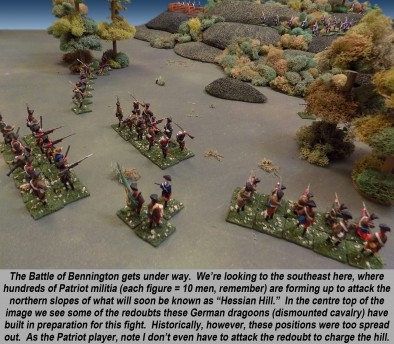

Stark saw that the Germans (reinforced by Loyalists, Iroquois, and a company of British sharpshooters) were well fortified on high ground north of the Walloomsac River, just across the New York-Vermont line. For two days his men probed the Crown position, unable to do much more because of intense rainstorms on August 14-15.

Finally, on August 16th, the weather was clear. Stark took a risky gamble by dividing his force, hoping to attack the German position from multiple sides. His men also managed to get closer to the Germans by disguising themselves as Loyalist militia. Finally at 15:00 hours, Stark launched his attack.

Although the Baum’s Germans and their Crown allies fought bitterly, they never really stood a chance. The American militia was also not “running away,” fired up when Brigadier Stark exclaimed: “The enemy is ours, or tonight Molly Stark [his wife] sleeps a widow!”

Surrounded and outnumbered almost three-to-one, Lt. Colonel Baum’s Brunswickers tried to break out by mounting desperate sabre charges on foot. Baum was mortally wounded in one of these charges, and his surviving men would soon surrender.

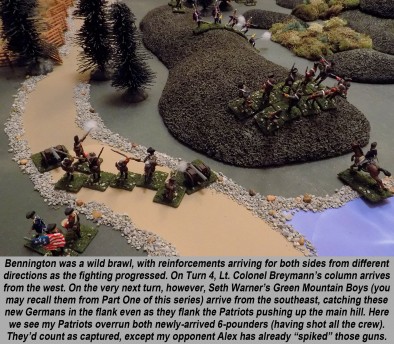

Yet news of this unfolding disaster had already reached other Crown forces. Another column of Germans, this one under the command of Lt. Colonel Heinrich Breymann, had already arrived and attacked Stark’s militia. Disorganised by battle in which they’d just defeated Baum, the Patriot militia was driven back.

Just short of dusk, however, yet another force arrived on the scene, some of Colonel Seth Warner’s militia, some of whom had fought at the previous Battle of Hubbardton (see Part One of this series). This was enough to halt Breymann’s column, which sustained heavy casualties and lost all their artillery in the closing hour of battle.

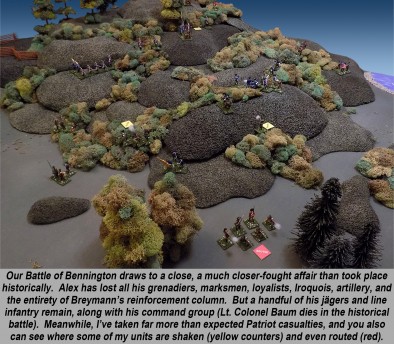

The Battle of Bennington was over. After the humiliation of losing Fort Ticonderoga, the defeat at Hubbardton, and the bloodbath at Oriskany, here, at last, was a clear Patriot victory. Baum’s force had been virtually wiped out to the last man (if you include prisoners). Breymann’s relief column had been badly mauled and driven back.

For Burgoyne, however, the bad news was just beginning. The results of Bennington triggered a congress among the Iroquois leaders scouting for Burgoyne’s divisions. A majority of them decided to quit, no longer convinced Burgoyne or the British were worth supporting. Burgoyne had lost the eyes and ears of his army.

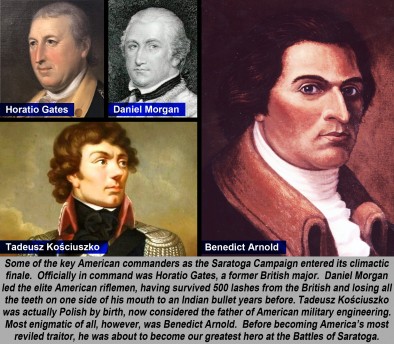

Still, things were not peachy in the American camp, either. For “surrendering” Fort Ticonderoga without firing a shot, the American commander (Phillip Schuyler, a man with many political enemies anyway) was finally fired and replaced with a general nowhere near as good, the former British major Horatio Gates.

Also, the Americans were hardly in a position to follow up on the victory at Bennington. After winning this battle, Stark, Warner, and most of the Vermont and New Hampshire militia simply decided they’d done enough. Now that Burgoyne’s columns had recoiled back into New York, his British army was no longer their concern.

This left General Gates with a rather small (but growing) force to stand against Burgoyne’s army, which was gathering speed again now that they’d finally reached the Hudson River. Fortunately for him, Gates had some stellar officers working for him, far better commanders than himself.

The first of these was Tadeusz Kosciuszko. Originally Polish-Lithuanian, he’d fought in Poland’s wars against Russia and Prussia. Now in American service, he applied his genius of engineering to picking the place on which the American army would fortify, and design the emplacements and artillery positions around it.

Then we have Daniel Morgan, leader of the famed “Virginia Riflemen” and widely regarded as the father of US Army Special Forces. He’d survived 500 lashes from the British during the French and Indian War, during which an Indian bullet had also smashed all the teeth from one side of his mouth … a seriously tough customer.

Perhaps even more important was Benedict Arnold. In the days before he was America’s greatest villain, he was one of America’s greatest heroes, easily the most effective leader in the Revolution’s northern theatre. At Saratoga, his courage and tactical command would win the battles that quite simply, make the rest of American history possible.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this third instalment in our Saratoga article series. Get ready, because in Parts Four and Five we will feature the First and Second Battle of Freeman’s Farm (historically, the Battle of Saratoga) – where the outcome of this pivotal campaign was finally decided.

Comment below, and tell us what you think of wargaming in this complex and dynamic theatre!

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"As July gave way to August, however, the British started to run into problems..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Fortunately for him, Gates had some stellar officers working for him, far better commanders than himself..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

![Very Cool! Make Your Own Star Wars: Legion Imperial Agent & Officer | Review [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2025/12/Star-Wars-Imperial-Agent-_-Officer-coverimage-V3-225-127.jpg)

Something I’m liking during this series is the awesome terrain and minis you have there @oriskany. So many people just assume all the old “Black Powder” era combat was done on wide, flat plains with no terrain around and you articles are really showing a good example of the reality of woodland battlefields. Enjoying these a lot and can’t wait for the next one.

Also I didn’t realise Morgan was so tough. 500 lashes would probably permanently cripple or kill you but he survived it and went back for more. Definitely someone I need to look into more.

Thanks very much for kicking us off, @elessar2590 – Indeed many of these battles in upstate New York were on very dense terrain … we had to “thin out” our Battle of Oriskany table last week for “player practicality.” Moving forward to Parts 04 and 05, we get to the First and Second Battles of Freeman’s Farm, which is a little more open and flat. Still lots of great terrain features, though.

Yeah, Morgan took 500 lashes during the Seven Years War / French and Indian War for striking a British officer. I certainly don’t think he took them all in one day, of course. I think for sentences like this would would take something like 50, wait a week, take 50 more, etc.

He’d also had all the teeth smashed out of one side of his mouth by an Indian bullet. So he certainly wasn’t in “pristine order” by the time of the American Revolution. 😀

In fact, technically he wouldn’t make it through the war. After the Battle of Cowpens in early 1781, he has to quit the field because of malaria, back problems, and some of the lingering after-effects of all these wounds. So yes, these earlier injuries definitely did have a lasting effect on him.

What always strikes me a little funny are the portraits you see of men like this. He always looks perfectly normal in the paintings. For a guy who’d taken a face wound like that (and reconstructive surgery was oh-so-advanced in the 1750s-60s) you have to wonder what he really looked like.

I picture the artist finishing the work and showing it to him.

“Wow, I really look like that?”

Yes, sir. Good as new, sir. That’s how we see you, sir. Please don’t kick our asses, sir …”

😀 😀 😀

Maybe that was just his Tinder picture and he wanted to look his best for the wenches?

That would be and uncomfortable meeting.

“Ooo, I’m here at the Bemis Tavern to meet Colonel Morgan, commander of the 11th Virginia. He seems really impressive and . . . Oh my God! You *cough* look nothing like your picture!”

Then again, I have to believe Daniel Morgan was enough of a badass that he would be able to do well with the ladies regardless. 😀

I mean look at guys like Mick Jagger and Steven Tyler. 😀

money & power beats ugly every time.?

Yep. I guess that means we all have a chance, eh?

The original plan for that hill was some old laundry and a hunter-green bedsheet over it to try to get a large hill effect. I was out trying to find the sheet at the store and not having much luck. Glad to see another solution worked better.

Yeah, @gladesrunner – I grabbed a bunch of my desert and arctic painted styrofoam hills and re-painted them the same green, This game me a lot more, which I was able to stack up like this to make the approximation of part of “Hessian Hill.” 😀

Big hills like this are kind of tough for people who must use “modular” terrain. I remember using the “bedsheets” idea for the bluffs overlooking Omaha beach back in the Worldwide DDay Challenge. We made it work … I guess … but it’s always an imperfect solution.

Loving this series. I also enjoyed the chat on the weekender regarding it. This war is wrapped up in so many myths it’s good to have some facts. I find it so interesting that British forces won so many battles but just couldn’t win the war. Perhaps if they hadn’t had such a soft approach at the beginning of the war around New York which allowed Washington to escape.Mainly because they realised they would have to make peace with the colonists once they were beaten they held back to much expecting a surrender that never came. And generals that just didn’t coordinate together very well. Also when France got involved the threat of loosing the sugar islands in the Caribbean was more important to Britain than the 13 colonies.There was so much going on that you never hear about with what today is considered important

Thanks very much, @denzien –

Glad you’re liking the series. We’re hoping to gather more comments to show that readers at Beasts of War are occasionally interested in this material, so we definitely appreciate your participation n the conversation/

There is definitely a mythological fog around a lot of this material, especially here in America.

The British indeed won battle after battle after battle after battle. 1776 is an unbroken litany of disasters for the Americans in New York, it’s not until Trenton that Washington scores even a small victory against the Hessians at Trenton (and Princeton, NJ against the British right afterwards).

1777 would prove no better, with Washington losing the Battle of Brandywine and Battle of Payone, which gives the British our capital city, Philadelphia.

Now by the European way of doing things, the war is over. You’ve beaten the enemy’s army several times, and taken his capital city. Game over.

Except the Americans aren’t playing by the European rules. Once it becomes clear to the British commander (General Sir William Howe) that the Americans aren’t surrendering despite all he’s done, he actually asks permission to retire in the winter of 77-78. It seems he knows that he’s “checked all the boxes” and it hasn’t won the war, and especially in light of Burgoyne’s defeat in upstate New York in October 1777, it will all be downhill from here.

ABSOLUTELY right about the generals not coordinating together very well. The most grevious example of this is Burgoyne’s plan which we see in Part One of this series. He was to drive south from Canada to Albany, where Howe’s army (or at least a large part of it) would drive north from British-occupied New York City and meet him.

The problem is, these plans had to be approved by Lord Germaine and Lord Frederick North, Minister of American Affairs and Prime Minister, both in London. It takes 2 months for a ship to cross the Atlantic in those days. So before Burgoyne leaves for Canada (again) in 1777, he gets approval for his plan. Then, after he leaves, Howe’s plan comes in for the invasion up the Chesapeake Bay to invade into southern Pennsylvania and take Philadelphia. It’s too late to retract approval for Burgoyne’s plan. Howe’s plan is approved. So Howe sails south out of New York City, while Burgoyne (with no idea what’s happening) marches south of our Quebec and St. Jeans, expecting Howe’s troops to meet him in Albany. By the time he hears that Howe (and Sir Henry Clinton, Howe’s subordinate) is NOT going to meet him in Albany, it’s too late.

Yeah, very bad coordination. 😀

I’m glad there is some catering for those of us who like our historical games. I grew up on Games workshop because it was easy to get hold of in the late 80s early 90’s but as soon as the internet came along with disposable income it was my first love of history that took over. 18th and 19th century are what interests me the most so the more I see here I’d gladly support it.

Thanks

Awesome, @denzien . Of course I can’t speak for the whole team, but comment count is a big part of what determines what kinds of articles I write going forward.

Of course the “biggest winner” was BattleTech, but that’s a completely different genre.

Within historicals, Team Yankee seems to be the biggest draw lately. 2016’s American Revolution Series stacked up quite a score, so I honestly though this Saratoga-specific series would draw a little more (especially now that I had the right miniatures and could do more of the battles “properly” with a real system). But no worries. 😀

The comments are much appreciated, and the best way to support more 18th – 19th century “black powder” content on Beasts of War (as least myself). 😀

a great read as others have said not the nice open fields you would expect.

Thanks, @zorg – indeed the terrain this far north was pretty thick. In Parts 04 and 05, though, we get into some of the farmland along the banks of the Hudson River approaching Albany, and so the terrain starts to open up a little. 😀

The more I read these articles, the more amazed I am that these people I have never heard of played such an important role in helping us pull away from the Dark Side 😉 Thanks for the history lesson and really great pictures to go along with it.

The “Dark Side” eh? 😀 😀 😀

Oh Benedict Arnold. You were among the best of us. Stupid man. 😐

but we have cookies? Lol

@zorg – would that be cookies or “biscuits” in the UK? 😀

My girlfriend @gladesrunner and I were kidding around about what the next global war might really be about, tea-drinking nations vs. coffee-drinking nations. As a citizen of the coffee-drenched US, I think you and I would sadly be on opposite sides of this conflict. But we’d have the Spanish, French, and Germans as our allies. However, your big edge would allies in Russia, India, and China. Our only hope would be mobilizing tens of millions of crazy Latinos and Latinas out of South and Central America. “Bezerker infantry” all cranked up on hard-core Cuban espresso! 😀 😀 😀

no we have cookies and sausage rolls as well, tea the best place for that is a river and cucumber sandwiches yuk.

See, I can’t even talk about “American” food, all our best chow comes from other countries … although we do put our own spin on it, I guess. 😀

that’s not true I have seen man v food you have great food I would be dead over their over eating.

😀 Maybe it’s because we dumped all that tea and biscuits in Boston Harbor … so we had to start stealing other peoples’ ideas for food. 😀

steal never just copying some good ideas that’s all.?

Sounds good to me.

Holy cow, Never knew how much we Europeans depended on hired or alliance based support in the Empire building days. Plus we didn’t seem to grasp the concept of giving Senior Campaign Commanders some scope to make decisions due to the vast geographical distances involved.

Hugely interesting series so far. Thanks very much.

Why do the fighting yourself when you can get others to do it for you. The problems with the conflict was that it was still I think a delicate political issue at home in Britain and in America and although I have no evidence to back it up I am sure the Generals were given orders about exactly how far they could go in terms of suppression of the population

Thanks very much, @bonesbs ~

Indeed, only about a third of Burgoyne’s army was actually British. This is why I keep writing “Crown” forces – and honestly so do most of the published books on the topic.

A third were British

A third were German (mostly Hesse-Hanau and Brunswick)

A third were North American of one stripe or another (American Loyalist, Native American Iroquois, or Canadian Ranger).

Now granted, this was up north, in what was considered a “subsidiary” theatre. British armies elsewhere in the Revolution (i.e., Howe’s / Clinton’s main armies of 1776-78) were much more British. There were some Germans, but the British proportion is closer to 80-90%.

The British are huge on this idea of using other people to fight their wars. As late as world War II, we have 150,000 (roughly) British dead, but 400,000 “Dominion / Commonwealth.” So the other 250,000 are Canadians, Australians, Kiwis, Indians, South Africans, etc. etc.

You can’t really blame them. The UK just doesn’t have the population base of say the US or USSR.

But the tradition is an old one.

As far as commanders having scope to make decisions … if anything guys like Germaine and North gave guys like Howe and Burgoyne too MUCH scope. They approved both generals’ plans, and couldn’t / didn’t revoke or amend these approvals when they came into conflict because of the times and distances and slow communication. The overall attitude in London seemed to be … “well, they’re professional officers. They’ll figure it out.” Except they really didn’t.

Now Henry Clinton (Howe’s second in command, left to command in New York City when Howe headed south against Washington and Philadelphia) does make some attempt to help Burgoyne, on his own, trying to help Howe’s plan, Burgoyne’s plan, and his own mission to hold New York City, all work at once. But’s kind of a case of too little, too late. We cover it briefly in Part 05.

Thanks for the comment! 😀

I would agree partially, @torros . There’s definitely a case to be made that the British military and political leadership didn’t see the full extent of the threat. The American rebels were misguided fools … but still “Englishmen” and therefore not “true enemies” like the Spanish or French.

I think what they didn’t realize was the fundamental shift that had taken place in at least part of the population, that they honestly DID NOT see themselves as Englishmen.

Also, a big part of British strategy in the war as late as 1780 was the recruitment of Loyalists. So they couldn’t go “crazy” with suppression if you’re trying to actively recruit and militarize one-third of the population to your side.

All that said, some Crown commanders really did cut loose on the locals in some cases. Johnny Burgoyne “gave stretch” to the Indians that led to the Jane McCrae affair. Banistre Tarleton and his Tory Legion manufactured thousands of enemies for the Crown in South and North Carolina.

So it’s case of … go too soft on the populace, and you encourage them to rise against you. Go too hard on the populace, and you force them to rise against you.

When the people who live in a given part of the world have finally made up their minds that they just don’t want you there, there almost isn’t a “right” answer at that point besides swallow your pride and get out. The British learned it in America. The Americans learned in Vietnam. The Soviets learned it in Afghanistan, the French learned it in Algeria. In cases like this, the “imperial” power almost always loses. 😐

@oriskany Jim do you have access to any of the writings of the radical whigs in Britain that made their way to the colonies?. From memory of my history classes at school I remember they wanted to promote Republican ideals in Britain. I couldn’t remember any more so went to Wikipedia (I know) and it kinda brought back memories . It said

radical Whigs’ political ideas played a significant role in the development of the American Revolution, as their republican writings were widely read by the American colonists, many of whom were convinced by their reading that they should be very watchful for any threats to their liberties. Subsequently, when the colonists were indignant about their perceived lack of representation and taxes such as the Stamp Act, the Sugar Act and the Tea Act, the colonists broke away from the Kingdom of Great Britain to form the United States of America. “Radical Whig perceptions of politics attracted widespread support in America because they revived the traditional concerns of a Protestant culture that had always verged on Puritanism. That moral decay threatened free government could not come as a surprise to a people whose fathers had fled England to escape sin. The importance of virtue, frugality, industry, and calling was at the heart of their moral code. An overbearing executive, and the threat of corruption through idle, useless officials, or placemen, had figured prominently in their explanations of their exile in America.” So “most” of the ideas the American Revolutionaries put into their political system “were a part of the great tradition of the eighteenth-century commonwealthmen.

Wouldn’t surprise me, @torros . The political movement behind the Revolution starts way back in the 1760s, when American colonists are definitely still “subjects of the Crown” – so I could certainly see English writings influencing American thought at the time.

But what really sets the fuse burning is the greedy, ham-fisted, and short-sighted economic measures put in place by the Crown, Parliament, and the Crown-subsidized monopolies like East India Trading Company (some of the acts you’re mentioning in your post).

This is the reason the Revolution starts in merchant- and shipping-oriented New England The whole idea of British taxation was kind of a red herring to get the people fired up, as they American colonists were some of the richest and least-taxed people on Earth. The kinds of taxes, tariffs, and trade/shipping restrictions that were causing problems were in fact only impacting big merchants like John Hancock. Its more of a trade war than a revolution of “ideals.”

At least at first, it wasn’t a question of rich vs. poor, or republican virtues vs. royalist “evil.” It was rich vs. rich, and who can get the common people rallied to their cause through propaganda and political agitation?

Of course, later (1775-76) the Revolution gets re-branded with more noble ideals as embodied in the Declaration of Independence. Certainly didn’t start that way.

It’s like a lot of things, a good idea comes along and everyone wants to claim some of the credit for it. We certainly aren’t innocent in this regard, a lot of Americans like to claim “credit” for the French Revolution of 1789 (as if that’s something you’d want to claim “credit” for). 😀

Sure, a lot of French officers and citizens saw the American revolution and carried back those ideals to France. But what we tend to forget is they already HAD these ideals, that’s why some of these people were supporting us in the first place. The most direct influence America has on the French Revolution is the crushing war debt with which the French treasury was burdened after the 1783 Treaty of Paris. France, and Louis XVI, never recovers.

This is another part of these article series I like, pay attention to the comments section and you learn even more.

Since the development of LF and HF, then later Satcom, Theatre Commanders have had the “vital link” back to Government so I wonder if the scope/remit to make decisions has improved or actually reduced in real terms?

Truer words never spoken, @bonesbs – the comments are indeed often the best part of the article. If for nothing else, it gives me a chance to go over material that wouldn’t fit in the actual writing. More importantly, it gives other history buffs a chance to add their perspective and thus expand the conversation, especially from a gaming perspective. 😀

Great article. Interesting how the town of Bennington is in Vermont but the actual battle site is in New York State. And how all these Vermont and New Hampshire militia basically go home after this victory because the war wasn’t in “their state” anymore. Great insight into how chaotic the American army was at the time.