The Four Levels Of Wargaming Part 4: Strategic Level Gaming

July 21, 2014 by crew

In our continuing series on the The Four Levels of Wargaming, we’re discussing games that present the “higher command” aspect of military operations. As we near the end of the series, we come at last to the most expansive scope of all, the strategic level game.

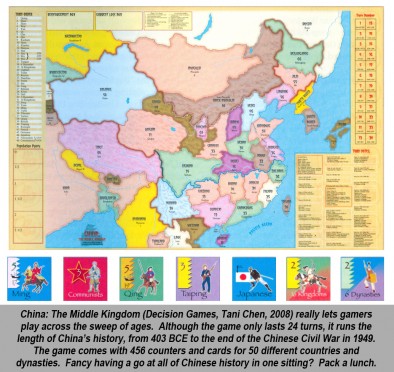

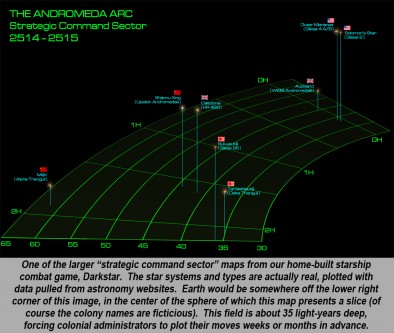

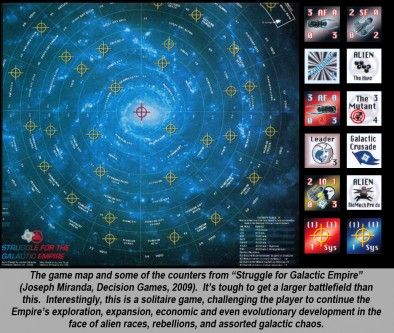

In a strategic level wargame, players control entire nations, coalitions, or empires. Therefore, if you “play” a captain in a tactical game, a colonel in a command tactical game, and a general in an operational game in the strategic game you take on the role of President, Prime Minister, or Dictator. Thus, these are no longer strictly military games, since you’re also running a nation’s diplomatic corps, political agendas, scientific and technological development, and wartime economy. In some games, even factors like religion and media relations are important. A single gaming piece could be a corps of 60,000 men or an army group of half a million. Industry production is tracked on charts measuring billions of pounds. Turns could represent anywhere from a month to centuries, in which case gamers are no longer heads of state, they are playing whole dynasties or perhaps the state itself.

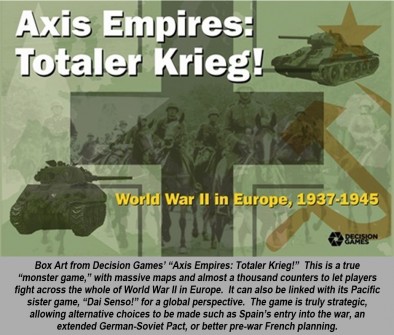

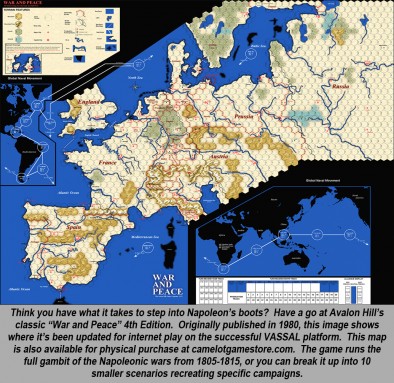

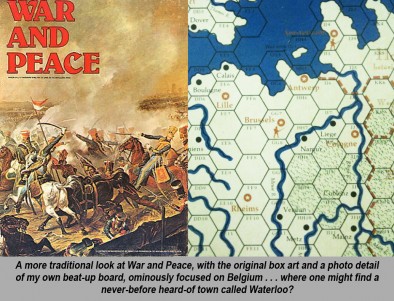

As we’ve said before, just because a game encompasses a larger scope doesn’t make it more complex, challenging, or “advanced.” After all, the case could be made that Parker Brothers’ Risk™ is a strategic-level wargame (admittedly, some would consider Risk to be a board game more than a true wargame). On the other end of the spectrum we have systems like Decision Games’ “Totaler Krieg!”, Avalon Hill’s “Rise and Decline of the Third Reich”, and ADG’s “World in Flames.” These games come with large maps, detailed rules, and thousands of counters—allowing players to movies fleets, armies, and air armadas across continents and launch million-man offensives the way some games fire off a burst of machine gun fire.

In a strategic game, even though a great deal of politics is involved, the coalitions are more or less set. In a World War II setting, for example, Germany is always an Axis power, although politics can be leveraged by both sides to influence whether Spain or Turkey enters the war along with them. The Soviet Union and United States are always Allied powers, although exactly when and how they enter the war is subject to all kinds of factors that the players can control and compete over.

I bring this up because some players may distinguish between “strategic” and “grand strategic” games. In the latter, players really do control the full course of their nation’s destiny. In a grand strategic game set in Game of Thrones, for example, the Starks of Winterfell may be allied with the Baratheons one turn, then turn on the Lannisters, and then finally cut a deal with the Targaryens. In such games, the balance of game play slides even more heavily into areas of economics, espionage, and politics . . . it’s theoretically possible to win without ever drawing your sword or firing a shot. Even in grand strategic games, however, there are usually absolutes. In our Game of Thrones example, it’s doubtful anyone will be entering an alliance with the White Walkers.

A great game that highlights this “free-politics” quality is Avalon Hill’s classic “Diplomacy,” where players represent one of the Great Powers of Europe prior to World War I. A word of warning, however, this is a cutthroat game of political double dealing so infamous that many have tagged it with the line: “Diplomacy – Destroying Friendships Since 1959.” Not that there’s any backstabbing in Game of Thrones. That whole Red Wedding thing was just a misunderstanding, right?

So far in this article series, one common thread has been highlighting how these larger-scale games can help construct meaningful narrative back to the tactical table top games so popular on Beasts of War. But in the case of strategic level games, this connection frankly starts to get a little thin. If you’re playing a Soviet captain ordered to hold a vital crossroads with six tanks and 75 guards riflemen, do you really need a view of the war from Stalin’s map room? Strategic games view war from such a high level that their potential for tactical narrative is tenuous at best.

That doesn’t mean they can’t help, however. A few years ago I ran a year-long series of tactical wargames and RPG sessions set in World War II. I used a set of Rise and Decline of the Third Reich to set up a “situation map” of Europe, Russia, and North Africa, using small bits of sticky-tack to fix counters on the board so I could stand the map up on an easel. Each week the pieces would move around a little, tracking the war’s progress. When my players arrived each week, I could kick off the session with a quick “situation brief” (complete with a little wooden pointer stick) that really helped immerse the players in their part of the war. But at the end of the day, it was more of a visual prop than an actual system we were running.

That being said, however, strategic games can be a lot of fun in their own right. They can also be very instructive for players who really want a deep-dive into a particular war or setting. For example, it’s perfectly fine for a Flames of War player to just accept that the Soviets will always outnumber the Germans, set up his game, and have fun. It’s also fine for players to watch a few TV documentaries and accept that the Soviets have bigger lists because “the Soviets had more men, factories, and logistical support.” But playing a strategic level World War II game actually challenges the German player to not only fight the Soviets, but balance resources with a war in North Africa and western Europe. Then there’s Sicily, Italy, and possibly Scandinavia, all while the British and American players are actively reducing your production budgets through strategic bombing. Meanwhile, the American player is pouring millions of men and billions of dollars across the Atlantic to staging bases in England. How much of your production do you put towards U-boats to try and stop that? How much foreign aid do you send to Turkey or Spain to try and get them in the war on your side? How much do you invest in security, with French, Polish, Russian, Greek, Yugoslav, Italian, and Norwegian partisans wreaking havoc across your lines of supply and communication? Only when you’ve been faced with some of these decisions (in a purely academic sense, of course) do you understand “first-hand” why those Tigers on the windswept steppe appear so lonely.

While they may not provide the tactical focus many of us are used to, strategic and grand strategic games offer the greatest scope of context. They present perhaps the final answer of “why is this battle taking place?” And not to get too heavy here, they’re also the closest a wargamer is likely to get to learning why nations are “forced” to go to war at all, what they hope to get out of it, and how (thankfully) these wars finally come to an end.

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact me at [email protected] for more information!

"“Diplomacy – Destroying Friendships Since 1959”"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"They present perhaps the final answer of “why is this battle taking place?”"

Supported by (Turn Off)

![Very Cool! Make Your Own Star Wars: Legion Imperial Agent & Officer | Review [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2025/12/Star-Wars-Imperial-Agent-_-Officer-coverimage-V3-225-127.jpg)

Love the series

Thanks very much! It’s been great fun to put together. 🙂

Now you just need to go on a trip to Northern Ireland and be a talking head on a Weekender

Wow, that’s high praise, especially considering I’d be in the company of BoW celebrity “consultants” like “Tank God” John Lyons and “Doctor” Dave. 🙂 I dunno, though. The way Warren and Lloyd beat up on poor Justin and Sam . . .

Actually headed to Normandy in a couple of weeks, though. And **hopefully** going to Salute 2015.

Sweet Awesome Sauce….

Thanks!

I have enjoyed reading your series and have loved getting a look at the gaming examples you have used. In your opinion what is the best way to represent fog of war in a strategic level game? Which games have you played which seem to offer the best fog of war aspect at this level. The reason I am asking is I teach a military history class and am always looking to add activities and visuals for examples and student interaction. Thanks again for the great series.

This is actually a really good question, one I almost feel ill-equipped to answer. The reason is because “fog of war” is typically a concept associated with the tactical or operational level games, which take place on a certain battlefield or campaign area. If memory serves (I feel nervous saying this to a history teacher 🙂 ), the term “fog of war” arose from the thick banks of white battlefield smoke in the days before smokeless gunpowder. Generals rarely ha d aclear view of the battlefield and garble important communication because the noise and smoke of the battlefield would obscure the bugles, drums, and flags used for communication.

To make a long story short, such clouding of situational awareness is something that I really haven’t run across very much in a true “strategic” level game. The turns are so long (a month, a year, or even centuries) that any such loss of clarity in intelligence or communication has enough time to get itself sorted within the span of time represented by the turn. Also, the playing pieces are so large (and the game so general in its high-level terms) that such “large blocks” of political, military, or economic capital aren’t very easy to hide. Finally, even when the enemy manages to “surprise” you, it’s usually a “month” or “year” before it’s your turn anyway and can do anything about it. This alone can represent that fact that your government and military needed significant time to recover from the shock of whatever happened.

For example, the Romans *knew* that Hannibal was coming over the Alps (strategic), but they may not have known exactly when and in what strength (operational). Hitler *knew* the Allies were invading across the Channel (strategic), but Allied misinformation, a confused German command structure, and just bad luck ensured that the Germans didn’t know exactly where and in what strength, or even if the Normandy were the “real” landings (operational or even tactical).

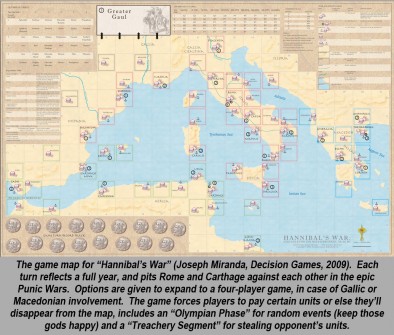

That being said, even heads of state have to make “wargaming” decisions based on incomplete information, so I’m not saying that Fog of War has no place in strategic level gaming. It’s just pretty rare. “Hannibal’s War” mentioned in the article does have a few rules on the subject, outlined below:

14.0 Fog of War

14.1 Your campaign markers should be kept face down, unless a rule specifically allows for another player(s) to examine them. You may also keep your total of talents secret, as well as your reserve of un-built units.

14.2 You may always examine your own forces, un-built units, talents and campaign markers. You may allow another player to see these things if you wish.

14.3 A player may examine another player’s forces at the following times: 1) during movement or combat, both involved players must reveal all the units in a square at the instant any units enter a square containing enemy units (however naval units, and any transported units, passing through a hex containing enemy land units may not see them; and 2) as a result of the play of certain campaign markers.

14.4 A player may voluntarily reveal his units at any time if he so desires. Otherwise, keep your units in each square stacked together in a single pile, thereby allowing only the top unit (of your choice) to be seen. There is no “stacking order” that must be observed.

This post is getting very long so I’ll wrap up. Since I feel like I haven’t made a useful recommendation on wargaming 🙂 , let me make up for it by recommending Philip Sabin’s book: “Simulating War.” Even though the book is a little densely-written (and the author a little self-serving about how smart he is), I bring it up because a great deal of its material is specifically aimed at using wargames as a teaching tool in the classroom. The book also includes a few “tear-out” games that can be set up and played in about an hour or two (to facilitate a classroom session), and easily accessible to students who have never played a wargame before.

http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/13410799-simulating-war

A great article, like all the others in this series. I particularly like the idea of using ‘light’ strategic or grand strategic wargaming elements to provide greater context to smaller scale engagements, thus helping flesh out the ‘why’ of any given clash of arms.

That said, I have long been a repressed megalomaniac, and the idea of commanding the fate of nations and influencing the arc of history (or alternate/fantasy world history, or ‘future history’) has a special appeal all of its own…

I know the feeling @vetruviangeek . While strategic-level games lack any kind of visceral immediacy or “smell the gunpowder” battlefield presence, there definitely is something to be said for playing the Soviets in AH’s Rise and Decline of the Third Reich, turning the tide on the German invaders, eventually launching a multi-million man offensive back into Poland (this is usually the biggest single shove the game produces). Picking up that d6, you can’t help but think . . . “the destinies of MILLIONS rest on this dice.”

Conversely, as the Germans its great to actually crack the Soviet Union. I’ve only managed it once or twice, but there’s a certain rush in watching Grossdeutschland Panzer Corps or XVLIII Panzer Corps rush toward OVER the Urals and actually peek into the first expanses of true Siberia. If you can do that, and invade England (wow, you’re good), I think the rules stipulate that America sues for peace and a new 50-year Cold War begins, but between the US and the Third Reich instead of Soviet Russia.

It occurs to me that one way to integrate strategic level and smaller scale games systems is to have the player of one side, or a coalition of players from the same faction/group of allied factions, setting some kind of general strategic level initiative in play, drawn in broad brush strokes, and then having to enact that policy on th operational and/or tactical level. So, the strategic initiative might be to target military production, break through enemy lines at a weak point, disrupt R&D, or launch a diversionary offensive to cover a special operations mission behind enemy lines, and that general strategic decision then informs the type of operational decisions made and the type of tactical scenarios played. This might offer a little strategic context and gameplay while still leving scope for more traditional wargaming mechanics to have their day in the sun.

Some old gaming buddies and I used to give that kind of “macro game” some thought, the problem we ran into was the sheer differences in scale between strategic level games and the lower-level games.

Say we’re using Third Reich, World in Flames, or Axis Empires (I’m sorry I keep using WW2 examples, it’s just what I know off the top of my head) for the strategic system. The Axis sets the strategic imperative in the Spring-42 turn: “Launch Case Blue.” Okay, that’s 2 million Germans and Axis allies driving for six months through the Ukraine, the Donbas, the Caucasus, and eventually to Stalingrad. That equals (just to use an extreme example) about 1000 Bolt Action games (200 men on each side) x at least 180 days of campaigning = 180,000 Bolt Action games. Wow. I hope your group like Bolt Action. 🙂

Of course this is a silly, extreme example, you’d use some kind of representative system (This is a “typical action” of this campaign, etc.). But even if you could work that out, you run into another issue, the number of different lower-level games you’d need:

*some kind of ground combat (obviously)

*aerial operations for Allied strategic bombing efforts

*a dogfight game for tactical battlefield air operations

*some kind of spy game for espionage / code breaking / sabotage

*a mechanic for competing technologies and countermeasures?

*a naval game

*a submarine warfare game (these would probably be different)

*a diplomacy game with random events for assassinations, etc.

*who knows what else?

Again, an extreme example. The group could resolve to just represent certain tank battles in Panzer Leader or Flames of War or Tide of Iron or whatever, and leave the rest of the strategic game to run itself in a conventional manner.

Long story short, I think strategic games just cover too much ground for a true integration, both in scale and variety. But who knows?

Yup, that’s a lot of Bolt Action games, even for a super fan of the system…

I see your point; with such a vast disparity of scale, it will always be difficult to integrate the different systems in a meaningful way. Still, I like the idea of having swanky strategic maps showing the ‘state of play’ and broader strategic context surrounding an operational, tactical or hybrid campaign, even if it plays no further role than that.

And as we have already noted, strategic games gratify one’s inner iron-fisted tyrant more than anything else… 😉

Like I said in the article, we had that Third Reich map set up for our tactical / RPG series (ah, Misha . . . my Russian tank captain), but it was more of a visual prop that an actual system. This was before we had our big Phillips flatscreen TV. I content to it from my laptop, these days I could use it for a cool “CIC tactical display” for a sci-fi or space game. 🙂

Nice informative end to the series @oriskany.

to be continued?

Yep, we have one more in this series . . . hopefully out next week. 🙂

The closest I came to that level was Total War on PC if you never played you can switch from emperor/king to field commander. In saying that I wasn’t that good at the fighting lost more men when I commanded the army. I go further when I concentrated on ruling and let the computer handle the battles I think the best I managed was half of Europe mid east and North Africa

Oh, man @zorg , I am terrible at computer games. Give me the Germans invading Poland and I would find a way to lose. 🙂 Unless it’s really a “computer” version of a traditional wargame as opposed to a “video” game (RTS or some such).

The best I ever did in Third Reich as the Germans was France and Russia, but couldn’t take England before the Americans drowned the island in little green counters. (“Substantial”-level Victory, I think)

Another time I did the opposite, Took France and England but couldn’t knock out Russia in the time allowed. (“Marginal victory”)

I did win very well with the Germans once in the late war 44-45 scenario (you can either do the whole war or parts of it). It you start the war at the beginning of 44, German WILL lose, it’s just a matter of when. Well, when the game ran out of turns in the fall of 1946, I still had armies along the Soviet-Polish border and the Americans/British were still clogged up somewhere in western France. Forget Italy. 🙂 Admittedly, my opponents were still learning the game, though.

Great article once again. I really want to play agame that includes a treachery segment…TREACHERY!

When I try to recreate a tactical level battle. I have a far greater desire to get it as close as possible to the history. With the victory conditions coming down to a “how well” or “how long” sort of thing. For some reason. In these larger games, I’m far more prone to dreaming of the “what ifs”. Of course, one favorite I’m sure I share with many is Hitler getting clipped, and the then western allies Join a hasty West Germany and have a throw down with the latest and greatest of the era. Pershings, Comets, Panther IIs all vs an ocean of JSIIs and JSIIIs.

Actually that would be a great tactical game, but the “how we got here” part, would be fun to play in stategic level game.

Good stuff again Oriskany 🙂

vetruviangeek said:

“That said, I have long been a repressed megalomaniac”

Aren’t we all…

Thanks, @amphibiousmonster . When I actually downloaded the rules for Hannibal’s War (the game with the treachery segment), I was mildly disappointed to see it’s pretty much limited to buying off enemy units. Think the big betrayal scene in “Braveheart” when half of William Wallace’s army just rides away . . . I was picturing all kinds of knavery like assassinating enemy generals with poison maidens, kidnapping their daughters and trading them off to barbarian chieftains, bribing/blackmailing enemy politicians to have their generals recalled in disgrace . . . Come on, man! It’s ancient times!

The “what ifs” are what strategic games are all about (at least historical ones). While the economics model, coalitions, and geography of Third Reich are all detailed and realistic enough to ensure that Axis will lose 75% of games . . . EVENTUALLY . . . the how and when are the big variables that determine which player wins the game. They also had variant counters that were a lot of fun, one of which was Hitler’s assassination. No Soviet pre-war purges was another, Hitler doesn’t interfere with the German jet fighter program (huge bonus to German defensive economic warfare points, since German jet squadrons are massacring Allied bomber formations), German agents start anti-British insurgency in Iraq (where have we heard that lately), improved British diplomacy ensures no Vichy French forces join Axis pool after the Fall of France, etc, etc, etc.

No “magic chit” to end the game in a single draw (Black Lotus in MtG 🙁 ), but little things for “what-if” flavor. I always found it interesting to see how little a difference some of these “OMG war-winner” variables actually made. Strategic-level warfare is just so big, that no single factor can ever really bring the whole system crashing down.

Thanks for the great series of articles oriskany. I was a great read and nice to hear about the games I have not played but others have enjoyed in this genre. I will never forget playing a game of World in Flames where Germany did not capture France until 1941 and did not attack Russia/USSR at all, drawing the Americans who had entered the war at this stage into re-enforcing the French lines. Germany then encircled France and wiped out all of the French, British and American units. By doing this Germany was able to focus on taking Gibraltar with a sneak attack by the Italians fleet with German units and also take the Suez canal. The allies had to rebuild their ground unit strength before they could re-engage Germany on the European map, and lacked forces to protect the Pacific. The axis held the Mediterranean. Changed the entire outcome of the war, with Germany and Japan ending up with a very rare win. Proved a couple of things to me. France had to fall and it was Russia who soaked up much of the German fury and bough time with Russian lives for the west to build up to defeat Germany, and the fight in Africa was crucial to the allied campaign in the pacific.

Damn, @mattgro . That sounds like a wild scenario in World in Flames. I guess if Germany was not yet at war with the USSR, they really would have 250+ extra divisions to engage in another World War I in France, this time really taking out the US, UK, and French armies.

Interesting bit about the assault on Gibraltar. There was a plan to do just this, but since Spain could never be fully drawn into the war, the Germans and Italians never really had the needed staging point. In Third Reich Spain rarely comes in on Germany’s side, just as often Germany declares war and invades across the Pyrenees once France falls. I wonder, if you remember, did the Germans/Italians ever take Malta in your game? That was the real lynch pin that held the central Mediterranean together for the British. Had that fallen, holding onto the Suez and possibly even Gibraltar might have proven very difficult.

You couldn’t be more right about the Soviet tying down and destroying 90% of the German war machine, at least their ground forces. THEY won that war. The British put in the time and the Americans put in the money, but the Soviets put in the blood. I’ll resist getting up on my soap box, but this is a huge thing for me. I could spew pages on this, but I’ve found that people get bored with my ramblings and . . . even worse . . . sometimes even take offense if they mistake my position for “belittling” American, French, or British contributions, especially if they had relatives in service at the time.

I would certainly never mean to do that, but the fact remains that over 350 of almost 400 Axis divisions destroyed in World War II were destroyed in the Soviet Union (some were destroyed several times over). Also, the combined military/civilian death toll of the US, UK, Commonwealth, and France (European and Pacific) is outnumbered by the Soviet death toll by about 40-1. No, that’s not a typo.

@oriskany, I do remember we didn’t take Malta, but it doesn’t provide any use to the Allies when their is no way to get to it. Took Suez from Lybia while the British were too focused on France and the German U boats, we snuck the 12-6 SS tank unit down there and played shock and awe, and Gibraltar was a full naval invasion the next turn with the entire Italian Fleet providing support. We did that the turn after France fell, using southern France as the staging area, deciding not to declare Vichy due to the dominant position and the units left in France. It is fun to get German subs on the pacific map, real headache to the commonwealth convoys.

I do agree with you about Russia, due to the cold war they were never given the credit due for the onslaught they survived and eventually triumphed over.

Gotcha. I understand, @mattgro , it sounds like you guys took the Mediterranean “the hard way” . . . from the outside in instead of the other way around. Take Suez in the east and Gibraltar in the west, leaving Malta in the center as immaterial . . . instead of the way it might have happened historically (take Malta in the center, leaving Suez isolated from Gibraltar and thus vulnerable to capture).

It also sounds like the Italian Navy was the decisive “what-if” factor that allowed the Axis to score these additional successes. I’ve always wondered about that. The Italian Army in World War 2 doesn’t have that great of a reputation (despite some pretty solid units), but their navy was actually quite good, with plenty of excellent modern warships, plenty of supporting bases and infrastructure, and a solid tradition in its officer corps. I’ve never understood why it wasn’t given more of an opportunity to show its stuff against the British Mediterranean Fleet. Some people say it was because the Italian Navy didn’t have aircraft carriers, but in the Mediterranean . . . would it really need any? With bases in Italy, Libya, Sardinia, Albania, and later Greece, Crete, and Rhodes? Italy comes “built-in” with a whole fleet of “unsinkable” aircraft carriers. 🙂 Maybe they never got the coordination nailed down between their navy and air force.

Nice article again, have really enjoyed reading the series and seeing some games that brought back some happy memories

For Fog of War our ultimate try was a Napoleonic game…where we did a smalish engagement

there were 4 junior commanders that had regiments on there own 3x2table in 28mm after that were 2 brigade commander who saw the same game being played out on a 6×4 in 6mm each and finally the overall commander who had there own 8×4 table and saw the battle being played out n 2mm. Made for some interesting decisions during the game for the overall commander but way too time intensive

Wow, talk about different scales. 🙂 I assume you guys had some kind of referee running things on the different tables? Keeping developments on one table constantly updated on the higher-echelon tables? That couldn’t have been easy. I’m sure “real life” fog of war might have had a hand there, with simple player and/or referee error.

We’ve tried “double blind” PanzerBlitz a few times, where one player has his units on a board on one room, and the other player has his units on a board in another room. A referee runs them both. Only when enemy units “appear” (spotted or fired or you blunder into them or whatever), is the enemy unit placed on your board. Sadly, you need a referee, which is never fun (at least for the referee :)). Also, it only works with smaller battles because there is just way too much to keep track of (the referee has to keep both maps . . . in his head, and these articles have shown what some of these boards look like), although taking lots of pictures with a smartphone camera definitely helps!

True aerial reconnaissance photos! 😀

It was a just a trial go at something different. I think we had 5 umpires on the day. As I mentioned before it was very time intensive and something we never repeated again

Yikes. Five umpires. That represents a lot of man-hours contributed by people who don’t even get to play. We usually can’t get one umpire/referee for double blind PanzerBlitz/Leader. I’m not surprised that the experiment you describe was not attempted again.

Great set of articles. I have been thinking about looking at how I can incorporate some of these ideas into a massive 40k campaign system. Please continue to write articles like this, very inspirational and interesting.

Thanks, @follypuff . 🙂 I’ve been trying to incorporate some 40K examples and ideas, since I know 40K is probably the biggest game on BoW or in the “wargame space” in general. My problem is that I don’t play the game myself and know next to nothing about the universe. I’ve been picking up little bit here on BoW, the 40K wiki site, and of course in the posted comments . . . when people bounce 40K ideas off the material presented in the articles.