The “Four Levels” Of Wargaming: A New Scope On The Hobby

June 30, 2014 by crew

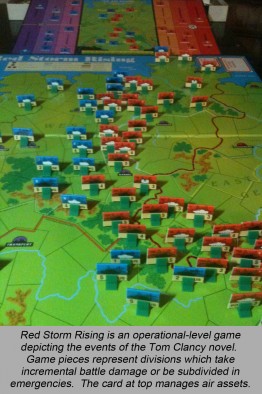

Wargamers would almost universally agree that narrative is one of the most vibrant aspects of our hobby. Only through such context can we answer the all-important questions of why we’re striving to take that bridge, town, castle, or spaceport. While great books and spectacular artwork go a long way in filling this crucial need, zooming out to view the larger “operational-level” picture is another great way gamers can provide this background. By playing (or at least reviewing) games that deal in these bigger pictures, players can get a real understanding of how certain battlefield decisions are made, and why certain scenarios in our familiar tactical games are shaped the way they are. Additionally, this can be done in almost any genre and in almost any medium of gaming (miniatures, computer games, or even hex-and-counter games). Even if a higher-level “general’s game” doesn’t appeal to you, understanding the basics of how these systems work can be a great help in building your own narratives for traditional tactical games.

Definitions may vary, but wargames generally come in four basic levels. These could be thought of as tactical, “command” tactical, operational, and strategic. Players may recognize other categories, and of course there’s always some overlap in a given game system.

The smallest and probably most familiar of these levels is “tactical” or “pure tactical.” Here, playing pieces represent individual combatants or vehicles, often with highly-granular rules for movement, firing ranges, and true line-of-sight. These games are fast, sharp, visceral, and deadly, and if this kind of gaming interests you, there’s a great site called “Beasts of War” you may want to check out.

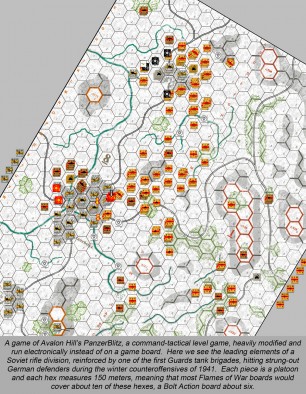

The next step up is sometimes called “scaled tactical” or “command tactical,” which simply represents a given engagement at a higher level of command. The map still represents a single battlefield (albeit a much larger one), and the game still represents a single engagement fought on a single day. But each playing piece now typically represents a platoon of 40-50 men in modern or sci-fi games. In black powder, medieval, fantasy, or ancients games, this number can go as high as companies of 200, cohorts of 600, or battalions of 1000. With 40 or 50 pieces per side, players now take the role of majors, colonels, or even junior-level generals, commanding thousands of men in combat.

This is the solution usually employed by history-heavy World War II players, American Civil War players, or Napoleonic players. Can you imagine Warren painting 200,000 minis for his game of Waterloo? Engagements like Gaugemela, Cannae, Agincourt, Martson Moor, or Gettysburg just wouldn’t be possible in a “pure tactical” model. Many of these command tactical games are still played with miniatures and terrain, such as GHQ’s Microarmor series, Command Decision, and even TSR’s old fantasy-based game Battlesystem. Other command tactical games, however, step away from miniatures in favor of more easily-managed mediums of gameplay such as computers or counters. Some players might consider such “command tactical” games just a subdivision of the broader tactical genre, but remember that when you’re dealing with units instead of individuals, the basic math driving all the game’s systems have to undergo fundamental changes.

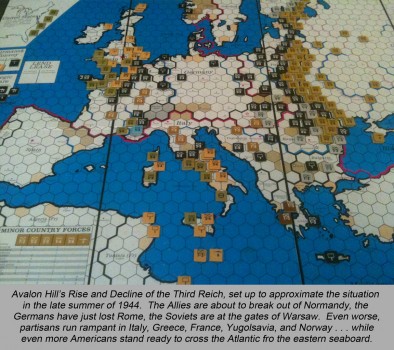

The highest level, of course, is “strategic” or “grand strategic.” Here, players take command of entire nations, coalitions, or empires. The map could represent the whole world, with each turn representing three months to ten years. In Decision Games’ Struggle for Galactic Empire, the map represents the whole Milky Way galaxy. Although still wargames, they also deal heavily in politics, diplomacy, economics, culture, and sometimes even anthropology. The simplest example is the classic Risk, although this level of gaming is better represented by games like Avalon Hill’s Rise and Decline of the Third Reich and Decision Games’ Totaler Krieg.

Between the tactical and strategic games, however, is the often-overlooked operational-level game. Here, at least in my experience, is where the real “dragon’s horde” of narrative gold can be found.

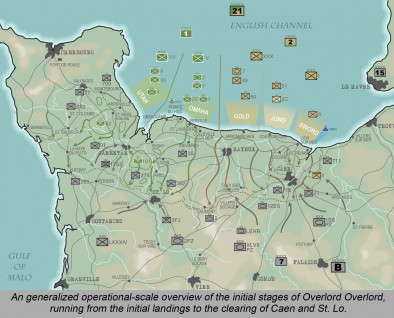

Simply put, an operational-level game conducts a campaign over a period of days, weeks, or sometimes months. The map could include the five invasion beaches of Normandy (as in Avalon Hill’s Overlord), a planet or star system in a sci-fi game, or the Holy Land in a game about the Crusades. Turns usually represent timescales ranging from twelve hours to a week, depending on the era. A game piece might represent a battalion (800-1,000 men) to a division (15,000-20,000 men), an air squadron, a naval task force, or a single capital ship (battleship or aircraft carrier). Crucially, they might also represent a supply column, logistics base, or tanker convoy.

Operational-level games differ from strategic games in that they are small enough to remain strictly military. Although there is a large degree of resource management, there are no “pure” economics, diplomatic factors, or shifting alliances. They also differ from even the biggest command tactical game, however, in that they never represent any single engagement. When an engagement begins, the combat strengths and characteristics of the units involved are usually compared to arrive at a ratio, various factors are considered, dice are rolled, and the results applied to both attacker and defender. There could be three, four, or five engagements resolved in a single operational turn, with dozens or even a hundred battles resolved before the complete game is finished.

Strictly speaking, operational-level games aren’t “campaign games” like the “Alternate Bulgaria” Bolt Action series we recently saw featured on The Weekender. Campaign games are usually a series of tactical games connected by an overarching narrative. True, a campaign game might have some operational elements built into it, like how far certain units can move on the larger map. But an operational-level game puts much more detail into the higher-level mechanics of military operations like logistics, shipping, airlift capability, and coordination with naval units.

Because operational-level games require significant resource management, limited intelligence (hidden movement), and heavy number-crunching, many recent releases have been computer games. Matrix Games’ Operational Art of War is a great example. Others stick to the conventional game boards, like the series of games regularly published in Strategy & Tactics magazine by designers like Ty Bomba and Joseph Miranda. Larger games include Diffraction Entertainment’s Blitzkrieg series, monster games which sometimes come with thousands of counters and 6-foot by 8-foot maps.

Clearly, there’s a much larger world of wargaming beyond the firefights and skirmishes in which we embroil our miniatures. Maybe it’s time to “get promoted” in your army, and see if you have what it takes at the general’s table.

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact me at [email protected] for more information!

"...players take command of entire nations, coalitions, or empires. The map could represent the whole world, with each turn representing three months to ten years"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Clearly, there’s a much larger world of wargaming beyond the firefights and skirmishes in which we embroil our miniatures..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

A veryngood article with the breakdown of the different levels. I think back to my Avalon Hill games day when you had those huge hex boards and played out huge battles.

Thanks, @stvitusdancern . Avalon Hill, those were the days, eh? They live on through their Axis & Allies line (not only the classic board game but also their miniatures games), but I think the really big hex-grid monsters are published by companies like Decision Games and Clash of Arms.

GMT and Lock’n’ load publishing are my favouriteds at the minute…West End Games Western and Eastern Tank Leader and Yaquinto’s Panzer Leader series are also up there

That’s funny, I just tried Lock n’ Load two weekends ago at our local gaming store. Was new to the system, obviously, and in trying to take a company of American paratroopers over a bridge, got my b***z handed to me by some German infantry backed up by a sIG self-propelled howitzer. 🙁

GMT tends to be my company of choice for these types of games.

Indeed, @redben. I’ve heard good things about their “Simple battles of History” line, which is probably a little basic for hard-core veterans, but serves as a great gateway for people new to this aspect of the hobby.

http://www.gmtgames.com/p-205-simple-great-battles-of-history.aspx

I haven’t tried SBoH but I do have SPQR from their Great Battles of History line.

Awesome, @redben . What scale is that SPQR game, if I can ask? Is each piece a maniple or cohort, something like that?

Great article and pics. The winterized versions of the original PanzerBlitz formats are really cool looking.

I excel-game hex games with Oriskany, and the options are really endless in the digital age. I whip up “custom” counters all the time with out worrying about the dreaded printer, glue and scissors of physical counters.

Thanks, @amphibiousmonster . People often ask, does running the game electronically really save playing time? Actually no, although it’s a helluva lot less annoying. Where it saves buckets of time, however, is in the PREP work. 😀

Nice article..Seeing some of those boardgames brings back memories and much enjoyment and also dread ( Western Desert and Atlantic Wall) spring to mind

Not to say strategic games cant be played with miniatures, I have played the entire Western Desert in 2mm on an 8×4 table which was also enjoyable

If anyone wants to have a go at boardgames there is a nice little website http://www.vassalengine.org/ which allows to either play solo/hotseat or online

Thanks, @torros . I know what you mean by dread, just setting up some of these boards to take photos of them, I was like . . . wow. I really used to play these? They can be daunting even for a veteran but once you get started, they’re great fun.

Great read. Never really looked at wargaming in this way before.

Thanks, @preston10k . Even if this isn’t “your” style of gaming (and for a huge part of the hobby, it isn’t), I’m hoping that just taking a look at how games work at this level provides fresh ideas for context and narrative for more traditional miniature games. Future articles will look at each level (especially “command” tactical and operational) in more detail, where I feel the best narrative can be found.

Not a problem. It really does interest me this type of game. I love campaigns and narrative style of games. I think it adds a little bit more than just dice rolling and measuring inches. I play mainly 40K But me and my friends have tried to expand campaigns to encompass the likes of risk and so on. The things GW realised have never really caught our eye but the break down here is inspiring me! Again a great read and I look forward to more!

Right, @preston10k . I’m half-hoping @warzan sets up a little operational-level structure (not a full game, of course) to frame out his upcoming Warhammer 40K campaign he’s working on.

This sort of gaming has been at one point part of GWs own arsenal.

Going going from small to large scale,

Warhammer Quest/Mordheim > WHFB > Warmaster/Man-o-War/Dreadfleet > Mighty Empires

So this variation of game scale while not new to scifi fantasy gaming, has in some ways dropped out of favour. Which is a shame because Warmaster is a great game system, and I feel better simulates the battles of the Warhammer World.

I didn’t know that, @doctorether , thanks! I doesn’t surprise me, though, I know GW puts tremendous investment into the background and fluff, and there’s no reason an operational-level framework couldn’t be built for a 40K campaign. Like Warren’s “naval landing” campaign he’s steadily building up?

Although I havent played it Strike Legion: Planetary Operations by Legionaire Games looks good

http://legionnairegames.com/Products.html you can download a cut down free version to have a look at

This actually looks really interesting, @torros , especially the customizable” aspect where you can build games . . . “set in any future you wish to imagine.” Thanks for the tip!

There is a WW3 version of that as well called Welterkrieg (same site) which uses the battalion as the basic manoeuvre unit

Essentially we had the same sort of thing for 40k, with,

Inquisitor > Necromunda/Gorkamorka//Kill Team > 40k > Warlord Titan/Epic Space Marine/Titan Legions/Epic 40000/Epic Armageddon > Battlefleet Gothic > Planetary Empires.

GW even had board games that operated on global levels, like the fight for the Craftworld against the Tyranids, or the battle for Armageddon.

The problem is, as GW has dropped all of these games, those really embedded into their games have to turn to other means to have those campaigns. Which is a real shame. And to GW detriment as other games move to fill those gaps at either end.

WW2 even

@Warzan…What has happened to the edit function?

Western Desert I remember when playing the Italians had to have more water allocated to them as they had to make pasta

Thanks for this article, I like your 4-levels as I think they’re distinct enough to differentiate some of the key feature of each.

I also think these levels give a certain flexibility to use a combination of technologies. The strategic game could be conducted using some IT based platform setting up lower level tactical table-top action. I used to love the mechanics of the Diplomacy board game; that mixed with the ability to do Fog-of-war at the strategic level. I guess I’m heading into “XX Total War” territory here, except the battles are on the table-top.

I wondered about trying this out with a skirmish game, particularly those set in a city environment, with gangs moving between sectors and players discussing potential alliances, setting traps, sharing intelligence etc.between simultaneous turns. Occupying resources earns you points to spend on more units/promote others. Where units clash – there’s your skirmish!

.

Thanks for the input, @coxjul , and thanks for “your 4-levels.” These are strictly my informal classifications, but having seen this many games, I hope they work for most players.

Combining different levels into a true “macro-game” is indeed possible. We’ve played home-designed operational-scale Eastern Front campaigns (Kursk, Manstein’s “Backhand Blow,” the Soviet drive on Kiev), zooming down to command-tactical to play out the actual engagements in modified variants of Avalon Hill’s PanzerBlitz. You definitely have a great idea about leveraging automation to run some of it, though. because this is a monster mountain of work. 🙂

This is now published a referenceable article through a recognised outlet (not exactly a scientific journal, but in the world of gaming it’ll have to do ;-), and so as far as I’m concerned these are now the “4 Johnson levels of gaming”!

The benefit of using technology for the strategic level is it would also allow players to run the campaign game through the week ‘between sessions’, getting to the point where the scenario for the tactical battle is ready to go for the face-to-face sessions, hopefully with lists etc already determined. Even if this is just by email with someone as a GM receiving the turn moves/actions and feeding back the turn outcomes to individual players.

“. . . so as far as I’m concerned these are now the “4 Johnson levels of gaming.”

Uh oh . . . Now I’ve done it. 😀

Perhaps look at Leaders: the Combined Game. Think Risk, with fog of war and command and conquer tech trees.

I’m also thinking ‘Omerta’ and similar for the city campaign idea – especially for a number of the steam-punk skirmish games.

That’s a great idea, @coxjul . . . especially because as I gro through these articles and try to apply the writing to all the genres . . . Steampunk is proving to be the toughest one. 🙂

Great article. Brings back memories.

Thanks, @nuclearmantc99m . Indeed, a lot of the games are “old,” but only because these are the games for which I own my own images. 🙂 There are lots of new games that handle these levels, many on the CD, others published for the tabletop by companies like Diffraction Entertainment and Decision Games.

Damn it, that was supposed to say “many on the PC” . . . although I guess a lot of them are delivered CDs, too! 😀

Thanks for mentioning the Diffraction Games. I looked them up, and WOW!!!! Their games look incredible. I used to be into the old Europa games. I love all that army detail. But Europa never put the whole war together. But Diffraction looks like they really could. I have to check it out some more. Didnt realize anyone made games like those anymore. But pricey!!!!

No worries, @garyjh22 . Yes, DE games are expensive, but that’s because you get huge maps and thousands and thousands of counters. Their games are massive, I’ve seen photos of full TSWW system map sheets set up at GenCon and I think you’d have to put an addition on your house to play the full sets at home. 🙂 If huge operational- and strategic-level games are your thing, it’s worth the $$$. But you have to be into that kind of game, because they can sometimes take hours or set up and days (or seriously . . . weeks) to play, especially their TSWW system.

I think they can be broken down into smaller theaters and campaigns – for instance, they have a TSWW set for Operation Ironclad in Madagascar in 1942. I’ve read about that campaign and I know the game can’t be THAT big. 🙂

All that said, they also make the Foxhole World War II Tactical/Operational Wargame Series, and the Ringmail Role-Playing Series, but I honestly don’t know anything about them.

Great article, may tempt me to rummage in the loft to try and find a couple of my old napoleonic games. Re @doctorether comments our club used GW Mighty Empires to run a campaign on a huge map on the strategic level and as we came into contact with other players it would lead to a table top battle. A lot of fun was had by all. Look forward to your next instalment.

Thanks, @ozzie . Yeah, operational or strategic games with “combat resolution” set up and resolved on tactical tabletops is a lot of fun . . . just kiss your family and job goodbye for a while as it’s a ton of work. Avalon Hill used to make a great Napoleonic strategic-level game called “War and Peace,” which I hope to mention in a future article.

Enjoyable article, thanks for taking the trouble. I have fond memories of playing SSI’s Outreach game played over half the galaxy. Now that’s what I call strategic. I still get all nostalgic when I see hex maps. 😎

Actually I think I mean SPI, not SSI.

Thanks, @brianparker . I’m curious if Outreach had a time scale. Decision Games’ “Struggle for Galactic Empire” is technically a solitaire game, and has a gigantic map of the whole Milky Way. But some of the actions include assimilating whole races and “evolving” your race, which made me think the turns could represent perhaps . . . centuries? Millennia? They never really said.

Also, in big space strategic games, the time scale can be very touchy depending on how the setting decides to deal with General Relativity and the speed of light, etc.

great read oriskany. You take me back to my childhood, watching a friends dad and his mates play Grand strategic games in the basement. A 8×6 foot board covered with a map full of units held in place with pins. I enjoyed the multi-level gaming in Battletech, going from succession wars the game through Battle space and Battle force to Battle tech and battle troops. It all came together well for MechWarrior, really added depth to the RPG.

Thanks, @mattrgo . I remember these Battletech games, and was glad to see the property is still alive with new material and minis coming out from a new publisher (Ironwind Metals, Topps, etc.). I used to play the FASA sister-game, “Renegade Legions,” which included both tactical space and ground-combat games and a larger, planetary system operational-level game called “Prefect”.

Renegade Legion was always far superior. Battledroids was only really released as a filler while FASA put the finishing touches to RL…Then put on a backburner when BT became so popular

Augh! I have found the ONE other person on Earth who ever liked Renegade Legions. 😀

This game became a literal disease for me, I had to “cold-turkey” quit it in 1996 and never looked back, but still can’t bring myself to throw away the books.

Well just so you dont feel alone my whole gaming group loved it

IMHO:

Interceptor: Awesome

Centurion: Even Better, blows the doors off of anything I ever saw for Battletech

Leviathan: Not so great, the ship classes became a little simplistic, as were the “game-killer” missile salvoes and simplistic blocks for handling fighter engagements.

Prefect: Awesome idea, with great elements, like EW/ES/ECM, Battlegroup/Task Force formation, and planets moving around a star as the campaign progressed.

Circus Maximus: Never tried it.

Legionnaire RPG: Pretty solid, but unspectacular. I did like the character generation

Once the IP was bought by Crunchy Frog, however (the Mysia Invasion) I think things started going downhill, and that’s when I jumped off the wagon.

I played it twice, and loved it. The armour/weapons mechanic in centurion was always my favourite rules, and enjoyed the computer game of renegade legion by SSI. The person who bought the game moved and I never saw it again, much is the pity…..

Nothing would beat pummeling a narrow hole in an enemy tank’s armor, marking off those little boxes, then sending in some TVLG missiles or gauss cannon . . . rolling the d10 for hit location, and as they say in the World Cup:

GOOOOOOOOOOOAL!

A quick note to everyone . . . APOLOGIES for the typos in the image captions. Most of these are drawn in Photoshop, which doesn’t have a spell checker! 🙁

I’m extremely happy and excited that you guys are covering at least a bit more than just minis wargaming. I’ve wanted article resources (rather than just me babble) to give to friends who want to learn more about wargaming.

Thanks, @leoleez – I was actually a little concerned that these articles might get a lukewarm reception since there are so many miniatures games here. But we had a feeling that there were lots of gamers on BoW who explore other mediums. 🙂

A very nice article there @oriskany.

Not having the space or time I have hardly played large scale battles like that often except on PC playing Tigers in the Snow (the bulge) and Total War (Europe/Crusades) for any time. Mighty empires was Warhammer’s Epic having played both games found them very enjoyable

@preston10k if you are trying to find out more about EPIC 40K try this website they should help you down that route. I don’t know if the company that continued producing epic material are still running couldn’t find them good luck.

http://epic-uk.co.uk/wp/

Thanks, @zorg . Indeed, higher-echelon games like this increasingly move towards PC gaming (or at the least, hex-and-counter), simply because of the level of resource management, requirement for limited intelligence (hidden movement), and the number of units involved.

Keep the good works coming.

@oriskany I used to play Circus Maximus with my Dad and Uncle all of the time. Loved that game.

I think it’s the one Renegade Legion game I never got to try. 🙁

Modern Spearhead is a 6mm modern set of rules which play at the divisional level.

The standard unit being a battalion.

I converted my epic 40K stuff to this system and we played some really interesting games.

An entire Space Marine chapter is really only two small battalions with only 14 Land Raiders, which converted to just 3 models on the table…..not really enough to do much against an Ork horde !

Thanks, @zellak ! So, 6mm armor, we’re talking 1/275 scale armor miniatures like GHQ? That’s a new system, though. Sounds interesting. Never heard of anyone converting another armor/mechanized system into 40K. Do you experience any trouble in converting unique unit abilities and weapons into the “rounded off” values of the larger game?

That was the easy bit, just took the best armour in the game (Challenger 2 ) and that equalled a Land Raider, then scaled down from there. Same with firepower Las-Cannon = Challenger 2 gun.

What was more interesting was trying to figure out how the SM and IG would work as battalions. IG Regiments have multiple Companies led by Captains (instead of Majors) , with a Colonel in charge of the Regiment….with no command structure for operating as Battalions……very strange.

The Space Marines are so few in number that we came to the conclusion that they would not be deployed as a battalion but used as special forces for small unique missions. Possibly sometimes cross attaching a single Company to an IG formation in unusual cases.

In a larger scaled game ,though it never really came across in Epic is that Space Marines were more likley to act as Fire Brigade team going into strengthen defensive lines and be part of an IG Army group rather than being an army in its own right

Wow, Land Raider = Challenger 2? I don’t know anything about 40K, but I guess I just learned something . . . that Land Raiders are bada$$ vehicles! And I didn’t know that Space Marines were so few in number. I always assumed they were rank and file. and not the “SEAL Team 6” of 40K. 🙂

As it was once explained to me more moons ago than I care to mention, the best way to understand the Space Marines is as one part special forces soldier (Seal Team 6, Special Air Services, that sort of thing), one part Templar Knight, and one part scary transhuman super soldier, all with a big dollop of sociopath on top.

Think of them as the diametric opposite of Star Wars Imperial Stormtroopers (so actually competent, able to find their own navels unassisted, and armoured in something more effective than tin foil) in everything apart from the nasty totalitarian mindset.

There are supposed to be somewhere in the region of 1 million Loyalist Space Marines all told in the Imperium of the 41st millenium divided into roughly 1000 chapters, but in an empire of a million worlds that is not much to go round, especially when one considers that the mostly human Imperial Guard (or should I say Astra Militarum?) ranks in the trillions of fighting personnel, and yet the Space Marines are there to do what the human troops cannot.

That actually helps, @vetruviangeek . I guess it’s obvious that I’m not a 40K player, but was trying to mention the game in some future articles and had totally mischaracterized the space marine concept. Thanks to you, I was able to make the changes before I submitted the draft to @brennon . Thanks for the save! 🙂

Is there a fifth level for things like the Megagames?

For those who don’t know: http://www.shutupandsitdown.com/blog/post/susd-play-goddamn-megagame/

I was toying with the idea of splitting “strategic” and “grand strategic” (I’d have five levels then) – but decided not to. Again, these are only my own strictly informal classifications, based not on the size of the game, but on the scale of events it tries to portray. By no means are they any kind of “official law” or “published dogma.” 🙂 Once you pass the point where the game is 50% economic, political, diplomatic, and in some cases even sociological, I classified it as “strategic.”

By this definition, even a tiny little coffee-table game like Risk would technically be classified as “strategic.”

Great summary/overview. I don’t do a lot of war gaming but when I play any sort of battle game… land air or space… it’s nice to know what’s going on behind the scenes to put me there.

That context and narrative is really what we’re aiming for with this series. As the series rolls out . . . I HOPE to provide a few ideas about how these higher-level games work just so players can imagine new, more textured ideas for background, narrative, and context in their pre-existing tactical miniatures games. After all, almost any skirmish is actually part of a larger battle. Soldiers don’t fight these battles for fun.

Speaking of operational level war games… Any one remember Panzergroup Guderian, Kharkhov, etc. from SPI back in the day? My first introduction to operational war games. Before that I only played Napoleonics on the ‘command tactical’ level.

I have definitely heard of those games, although sadly have never tried them. 🙁 Particularly on the Eastern Front, there are SO MANY operational-level games, with varying degrees of quality, of course. Coming from SPI, though, the games you mention were probably awesome.

oh this makes me feel so old. I actually remember moving little stacks of 1x1cm cardboard pieces on a massive paper map. Took ages to set up, and someone invariably managed to not knock over some of little stacks, scattering the pieces all over. How to find out what went where? I dont remember the name.. was it the battle of the bulge perhaps?

These are old school hardcore grodnard boardgames that I thought had gone the way of the telegraph when home computers enter the fray and playes no longer had to do all the numbers and fiddle with little bits of papery cardboard themselves.

I will confess, @maledrakh , that even when we play hex-counter games, we no longer play with physical pieces. The map is pasted into an MS Excel workbook, with hundreds of counters added in as “floating” .png images over it (see third image above, PanzerBlitz). You can zoom in and out, save a game and play it later, project it up on a 60″ plasma, and no one can “knock it over.” Best part, you can save the file after each turn, keeping a turn-by-turn record in case you suddenly realize you made a major rules mistake back on Turn 3 or something.

I am having grand visions of integrated campaign systems using all of these levels of wargaming, allowing the players to do everything from setting the grand strategy to deploying the units tactics to make it happen ‘on the ground’, with more conventional tabletop games coming about as a consequence of strategic imperatives – a sabotage mission becomes spiking the guns to pave the way for an amphibious/orbital (delete as appropriate) invasion.

To use a 40k anology, it woud cover everything from Kill Team to Battle Fleet Gothic with more besides.

It sounds incredible and really rather daunting in equal measure.

Biggest game like that we ever tried was was a Renegade Legions planetary invasion about 20 years ago, when I was still young and foolish and could stay up all night. we turned out living room into a war room, with maps hung on all the walls covered in clear plastic so we could write on them with dry-erase markers. We basically ran one single turn of the “Prefect” star system operations scale game in Prefect, Leviathan (mass starship combat), Interceptor (fighter combat to interdict/cover the atmospheric drop), and Centurion (grav tanks and infantry on the ground for the planetary beachhead).

We started at 5PM Friday, and finished one “Prefect” turn at noon on Sunday . . . 42 hours STRAIGHT. One of our players was literally sobbing in tears at the end . . . I’m not kidding. It was great fun, and we still talk about that game today, but honestly, we never did it again. 🙂

We’ve done a few big games over the years but nothing recently

Biggest one we did was in the late 80’s early 90’s using combined arms representing a Rumanian attack on Hungary

18 6×4 tables 35 players, two command areas where the commanders couldn’t see any of the tables but had lots of maps and walkie Talkies, and a very old VHS camcorder and a dodgy ladder for doing air recon

Good God, you had us beat on players, that’s for sure (I think we had six, which might have have been part of our problem).

Yeah, these super-games I think are best left in the warm, cherished memories of my twenties. Now when I stay up past midnight I’m usually worthless the next day, Forget pulling the all nighter!

Great article and wonderful references.

So far Battletech (BT) is the only game system I’ve played at all levels you’ve mentioned. I also think there is a fifth which you didn’t: the RPG level of playing a single character in the campaign. In BT we usually pull out the BT:Time of War RPG for infiltration and sabotage missions where only one to four people (not Battlemechs) are needed. I suppose you could lump it in with the single unit tactical level but I always feel its a deeper and different experience growing a character rather then just getting into combat following the rules.

That is true, @liono . If you consider an RPG a “wargame” then it would constitute a fifth level, where a player is literally deploying “An Army of One.” 😀

Yup a full spacemarine chapter has only one thousand fighting men if you are interested in playing it go 30K the armies are ten or twenty times larger because of the Horus Heresy they shank the armies to stop the marines getting to powerful again.

I’m hearing that from a lot of people. Like @warzan says : What do we like best about 40K? 30K! 🙂 So is a “chapter” of 1000 like a battalion that all deploys at once? Or are there 10 on this planet, 20 on that planet, i.e., Navy SEALS? If I want to write a little about “operational-level” gaming and toss in a few 40K ideas, I don’t want to sound like a complete tard. 😐

Well a Chapter is a spacemarine army could be imperial fists, or blood angels, ETC that is the hole army. Apart from the space wolf they are 12/1300 strong as they don’t follow the Codex and maybe one or two other chapters. Each chapter is divided into 10 Company’s of a hundred the first is the (veteran) Terminator equipped for the very worst jobs like storming a fortress or space hulk 2-6 are battle company’s 6-9 are reserve company’s 6/7 are all tactical (standard) marines 8 is a assault (fast attack, jumppack, bikes) company 9 is a devastator’s (heavy weapons) company the tenth company are scout’s (fresh green) marines.

I would say they were a combination of navy seal/coastguard/crusader/FBI all rolled in to one they patrol, guard, scrutinize, and attack any enemy of the emperor they meet or if their Captain command’s an attack on a planet to say get an artefact or kill a dignitary that disrespected the Chapter spacemarine Chapters follow they’re own doctrine and have attacked other Chapters because the Captain’s argued over territory for example some have.

They can easily be split into 5 or 10 man squads to advise a planets defences or an asteroid scanning for alien spacecraft entering imperial space. What has to be remembered is the nearest help could be a day week month or years away. So that man on the wall could be the only man for a long long time in saying that a spacemarine can live for 4 to 5 hundred years.

I hope this helps get your head round things a bit

That’s definitely a useful primer, @zorg . Thanks! In some of the articles coming out I was talking about a some larger-scale battles and trying to give ideas in different genres. These tips came just in time for me to correct one or two silly examples I’d included about a system and setting I really don’t know. 😐

No problem @oriskany you should get some of the 40K novels if you get the chance I think you will love them plenty of action & killing what more does a good book need. LOL

Like they say on Beasts of War: “Always err on the side of carnage!”

Excellent article. Thank you!

Thanks @drowningharvey ! Hopefully the follow-up articles will get this kind of reception as well!

Does anyone know if Canada Simulations are still going?

One of my favourites was Ambush by Victory games.One of the best solo games produced

Wasn’t Victory Games a partner with Avalon Hill? Division? Subsidiary? Or did they just share the same advertising venues, because I remember their games always appearing in the same ads and magazines.

really good article guys!

Thanks, @llopez0010 . Glad you liked the series!

Great stuff just reread it, due to the 50 articles

Thank you, nice series, I used some of this info for my most recent post for introducing new players into wargames. Is in spanish but you can take a look at:

http://wargarage.org/articulo/que-son-los-wargames-o-juegos-de-miniaturas/