Behind The Board Games: Johnny Fraser-Allen Of Tabletop Troubadour

January 24, 2019 by dracs

Johnny Fraser-Allen is a sculptor and artist who has worked on movies with Weta Workshop for the past fifteen years.

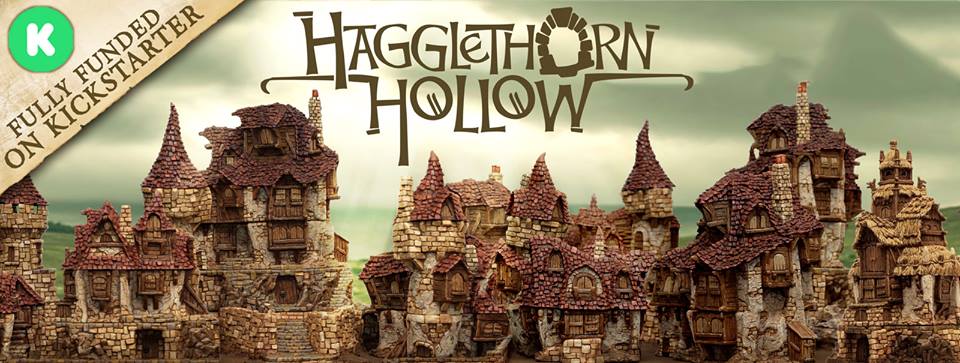

Johnny recently turned his skills to the tabletop, providing the miniatures for River Horse's board game adaptations of Jim Henson's Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal. Last year, he made a splash on Kickstarter with his company Tabletop Troubadour's new range of tabletop terrain Hagglethorn Hollow.

He also likes Tom Bombadil, so you know he's cool!

Sam: How did you first get into tabletop games?

Johnny: As a young child I was always drawn to the board games our family had which involved tactile elements, in particular, ‘Lost Valley of the Dinosaurs’ which in addition to the cool plastic miniatures of various dino’s and hunters had an active volcano with lava tiles acting as the game’s ticking clock.

My first ever job at the age of four (in order to keep me well behaved at kindergarten) was to select one new ‘Thundercats’ action figure from the catalogue each week, a task I did not take lightly as I was, and have always been, obsessed with creatures, and being a child of the 80’s meant I was oversaturated in the monster crazed toy boom! This meant I was always actively at play with multiple worlds of creatures at war with each other, ‘Dino Riders’ vs. ‘Battle Beasts, ‘Ninja Turtles’ vs. ‘G.I Joes’, etc: But even at an early age I remember struggling to give the imagined scenarios satisfying structure, any outcome I could imagine was possible, which did not resemble daily life, and these toys and characters were my life. What I was looking for was a fantasy setting to lose myself in where an understandable rule set was in place, allowing me the freedom to invest in characters that at some level were outside of my omnipotent control. Enter ‘Heroquest’.

My older cousin James had a copy of ‘Heroquest’ and it blew my mind. I had never seen it in stores as New Zealand in the late 80’s/early 90’s was drastically cut off from the world’s commercial market, so I only got to play it once or twice a year if I was lucky. The way the flat, empty board opened up from four heroes on a staircase tile to a fully working dungeon full of monsters was nothing short of magic, and to be quite honest, still is.

During one of these trips to see cousin James I was introduced to Jim Henson’s ‘Labyrinth’ and ‘The Dark Crystal’. It’s the earliest memory I have of physically feeling myself change as a person. Here was a world I could understand. I obviously never realized at the time just how badly I struggled to grasp the everyday human-world, ‘Learning difficulties’ and ‘Attention disorders’ weren’t terms that came about until my teens, and as an ‘adult’ I have to admit I still struggle with the day to day of being a person now, but those films filled me with a burning love of fantasy while those action figures nurtured my capacity for play and storytelling and the board games informed a style of play that kept my interest.

S: When did you first get started as a sculptor? How did you make that leap from a love of monsters and world building to designing your own?

J: It took most of my life to grow enough as an artist to get what was in my head on to a page or into the clay. Growing up with physical monster toys in my hand around the clock lead me to attempt my own, the earliest being cardboard cutouts pinned together as a six year old, to later attempts from ten to seventeen at sculpting over existing action figures. I have drawn my own characters my whole life. I HATE the idea people hold that one has a ‘gift’ when it comes to art. The only reason anyone in this world is good at anything is because they worked at it. It took me drawing every day from two years old till about twenty-three to finally begin to really get what was inside my head, out of it.

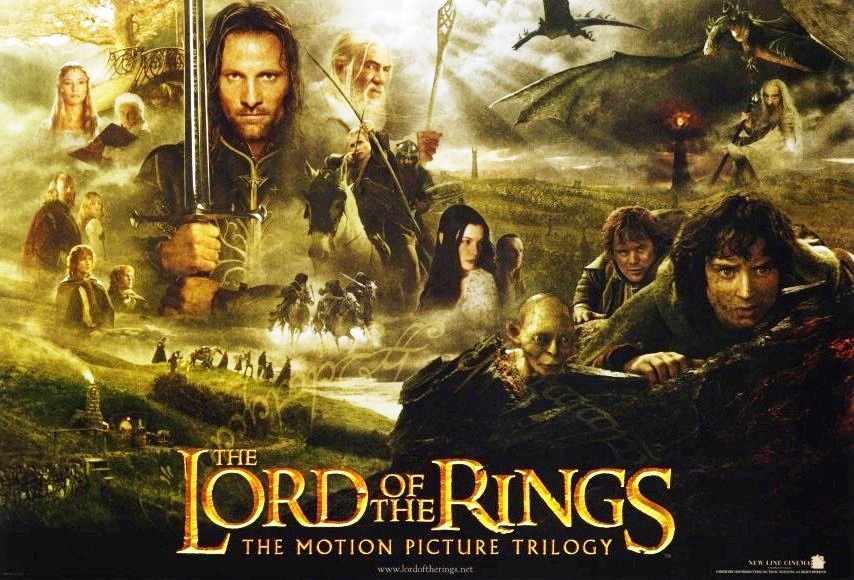

All I had ever wanted to do was create my own worlds. I had not long discovered ‘The Lord of the Rings’ at the age of fourteen when I heard that Peter Jackson was adapting them in my own country for the cinema. Upon further research, I discovered that all the design and fantasy fabrication were being done by a company called Weta Workshop. Long story short, I was working there by nineteen.

I reconfigured my entire teenaged high school career to build a folio to get me a job there. I changed high schools to attend a more arts-driven one, signing up for Design, Photography, Painting, Sculpting and Creative Writing… all failed:

- Design: They didn’t accept my fully illustrated guide to the Fairy world; they wanted a redesign of the Starbucks logo.

- Photography: They didn’t accept me making costumes and makeup to shoot my friend and family in a retelling of ‘Fellowship of the Ring’; they wanted cups on tables.

- Painting: They didn’t want an in-depth study of the suffering of Gollum as seen from the Raphaelite period; they wanted a black square on a grey canvas.

- Sculpting: They didn’t want a fully armoured goblin with realistic skin pore detail; they wanted a stack of vintage books on a stick.

- Creative Writing: They didn’t want a fully illustrated in oil paint ballad of how a Gnomish rogue rescued the princess; they wanted an essay on how 9/11 made us feel….etc

The more my creativity got repressed by the school system, the more I realised just how much I truly needed it to retain my sense of self and my happiness. I left that school for another in a last desperate attempt to get a qualification and found a place much more suited to my needs. I topped my film and design classes, framing my year of design around reimagining The Wizard of Oz for a folio to show Weta. It got me the job and I left high school to begin what has now become a 15-year career at Weta Workshop, and that’s where my real education in design and sculpting began.

S: Who and what are your great inspirations?

J: Creatively, early childhood inspirations were the complete works of Jim Henson (especially ‘The Storyteller’ which to this day remains the greatest treat I will gift myself every four months or so).

The action figure lines of He-Man, Ninja Turtles, Thunder Cats, Battle Beasts, Dino Riders, and G.I.Joe along with their accompanying T.V shows. Moving into my early teens were the written works of J.R.R Tolkien, Brian Jacques, Terry Pratchett and my favourite book of all time, H.G Wells’ ‘Island of Dr Moreau’. The artwork of Ralph Mcquarrie, Brian Froud and Tony Diterlizzi, the films of Laika, Nightmare Before Christmas and more than anything else in my ‘Adult’ years I am creatively fuelled by the music of Tom Waits.

S: You’ve done a lot of work for various films, which was your favourite to work on?

J: I Promised myself at eight years old during my birthday party screening of ‘Hook’ that I would work for Stephen Spielberg, which I have done twice now on ‘TinTin’ and ‘BFG’ but I have to say that the two years I spent working closely with Guillermo Del Toro on his design team to create his vision of the Hobbit was my favourite film-related experience.

The design meetings and workshops were an education in themselves, but for me personally, it was the twice a week visits to his home where he had me tutor his wife and daughters on sculpting and illustration that meant the most. The conversations we had about art and creativity itself broke down walls for me and informed my style in a huge way.

S: Did you learn anything working in movies that you were able to bring to sculpting models and terrain?

J: I learned everything! Before starting at Weta Workshop, I had spent years in my parent’s garage making scenery for Warhammer and LOTR games. You have to appreciate this was before the age of YouTube, we didn’t even have the internet at home, and my crafting knowledge was limited to my ingenuity and an occasional White Dwarf magazine. Then I started at Weta in the miniatures department of King Kong. That film had three times as many miniatures in it as the ‘Lord of the Rings’ trilogy did alone and I worked on all of them.

Starting in a team with one other guy, which over the years grew to sometimes twenty. I went from black foam card, dry brushed in white paint, to real rock-molds, airbrushes and washes overnight. Some of the terrain scenery seen in the Hagglethorn Hollow Kickstarter video was made in that first year over a decade ago from what I had learned. It woke me up, and it showed me that there were ways I could push the craft of tabletop gaming that hadn’t been done before, but at that point, and for the next thirteen years or more, it would only be for myself and personal tabletop.

S: Can you tell us a bit about your design process? Where do you start when making a model?

J: It has changed a lot over the years as I have grown as an artist. I used to draw a lot more than I do now before starting a sculpt, but I’ve since learned that I really enjoy finding the character as I go. I spent my entire twenties creating an immersive fantasy sculpture based world called ‘The Gloaming’.

I learned on that project just how much I liked being surprised by the outcome of my sculpture, so when I started ‘Hagglethorn Hollow’ I treated each building like it was a cool creature I was yet to discover, I never knew what was going to pop out of the clay, I just let myself feel each building, and drove the sculpture towards my personal tastes as a designer and requirements as a tabletop gamer.

Moving into Tabletop Troubadours next campaigns of: ‘Tree Creatures’ and ‘Wizarding Castle’ I have several notepads next to me filled with quick sketches that just capture ideas quicker than I can write them, it's been very helpful. With my work on the ‘Labyrinth’ and ‘Dark Crystal’ miniatures, however, I just started with the clay and found the character as I went with a wall of screen grabbed reference in front of me, but to be fair, I started with a perfectly formed idea of who and what those characters were.

S: Do you ever use computer modelling techniques, or do you prefer traditional sculpting methods?

J: In my fifteen years in the film industry, I have watched the medium of conceptual design move from pencil/pen and ink to Photoshop and then to Z-brush. Now, if you can’t design a character or environment in Z-brush, forget it, no job for you. In absolute honesty, I’d like to unequivocally state that I think that’s the way it should be! Designing for movies isn’t glamorous, you need to pump out 5 amazing designs a day on a team of nine people all working on one character for several months so a director viewing a few of the designs on his laptop on his yacht can ask his producer to maybe comment on some of them so you can start again next year. Z-brush is a tool, it’s a step up from Photoshop, but like Photoshop, it’s only a tool to make you a better and faster artist, beyond what you could achieve in reality. I can paint amazing things in hours in Photoshop that would take me months on a canvas. Likewise, I have seen artists sculpt things in Z-brush to a level they wouldn’t hope of reaching in fifty years of practical sculpting. It's all one big cheat, but absolutely necessary for the quick and harsh world of film design.

In terms of what it cost me both financially and physically, I’ve begun to think of it as a severe character defect, but I personally don’t consider anything ‘Art’ unless the Artist has both suffered for it and earned it. Yes, my years employed working in Photoshop have made me a better artist, giving me a greater sense of depth, colour palette, layout and contrast, but I am yet to ever look at a piece of photoshopped art and want to hang it on my wall. Likewise, I have seen many Z-Brush creature sculptures that are next level in design, texture and anatomy that become just so overdone and forgettable when compared to the craft and actual talent poured into the practical effects of ‘Dark Crystal’ or ‘Empire Strikes Back’.

It's all just an opinion, but at the end of the day there is something in me that drives a focus on what makes me happy, and that’s pushing mud with a stick til a goblin comes out. I haven’t made life easy on myself, but as I say, show me one thing that ever amazed you that was come by the artist easily. That’s the sentiment I put into ‘Hagglethorn Hollow’. If I had made it all digitally I would have saved myself many tens of thousands of dollars, but it was all about the hands-on craft. I started on Hagglethorn long before I ever saw it as a product, I was only making it for me, and only because I was unsatisfied with the straight-edged, symmetrical Z-brush sculpted buildings available for me to buy. I wanted a lopsided, hand-sculpted feel to a city that towered above all the ones on the market that had to meet moulding, casting and shipping costs. Hagglethorn was purely an investment in my personal craft and imagination and I’m thrilled it happened to find its audience after that fact.

In short, digital sculpting is to the art world what auto-tune is to the music world; there are millions of people that enjoy listening to an auto-tuned song and singer, it doesn’t bother them, some can't even really discern the difference, then there are the rest of us who want to hear the real talent of Tom Waits and Robert Plant. For me it’s that simple.

(Disclaimer: I am not in any way comparing my personal sculpting or art to the talent level of the aforementioned musicians, only using them as a means of actual talent vs. digitally aided artists.)

S: What do you think are the most important things to keep in mind when designing something?

J: This is a good question, but a tricky one, for a designer it's usually so specifically related to each individual brief, i.e: I would design a very different creature for Guillermo Del Toro for the same brief as I would for James Cameron due to their drastically different sensibilities as filmmakers etc. But, having spent over a decade working towards being in a position where I am fully employed by my own company to pursue my own creative visions, I would have to say that knowing yourself, knowing what has informed you as an artist and why those things meant so much to you personally, is important.

More important than that is the ability to take the things you love most and conceive of how you would make them better, and what ‘making them better’ means to you personally. Once you have that locked down, stick to it, don’t worry at all about anyone else’s opinion because only your understanding of your own opinion counts. If you have an artist you admire I can guarantee you they didn’t get to where they are from following the leader. If you have even read this far at all, you are either my dad (Hi Pop!) or you are a passionate tabletop gamer, which means you are both highly imaginative, and in the scheme of the world, very privileged. This means that, like me, you have more opportunity to manifest your own destiny to the outcome you desire than the majority of the planet; no one will ever care what level your chosen computer game avatar is on, but you have freedom to put your hours towards greater things, and in this age of gaming renaissance, it's all very exciting.

S: You’ve mentioned before how much you appreciate good world building. What do you think signifies good world design?

J: If I had to boil it down to one single thing its ‘Visual Cohesiveness’, the dominant artists stroke over a richly conceived world. The quickest way I can sum this up is by these compressions:

Ralph Mcquarrie’s ‘Star Wars’ vs.’’The prequels’

Brian Froud’s ‘Dark Crystal’ vs. ‘Legend’ or ‘The Neverending Story’

It’s what makes the difference between, ‘I enjoyed that’ to ‘That was f$%#ing genius!’, and that’s VERY important. Another main thing I focus on is realism. I’m obviously very fantasy driven in my personal work and abilities, but good fantasy has to be based in reality. This first really hit home for me with the ‘Fellowship of the Ring’ movie. Every building, creature and costume had a strong basis in reality, no overly large chrome amour, no ‘witchy poo’ goblin noses, just a higher level of thought behind each design. I think no matter what your personal style of art is, those are two foundation stones to build from. From there it can stray anywhere and still have a chance of being great.

For me personally, what transcends good design to incredible design is always based in the practical. Something craftsmen have constructed in reality will always be better than digital. It’s the difference being pulled into a world and just wanting to eat popcorn, it’s the difference of the Echo base set in Empire compared to the greenscreen backdrops in Attack of the Clones, it’s the hand-carved masonry and painted backdrops of Labyrinth, the glass painted scene extensions of Willow and it’s the hand crafted miniatures sets of Box Trolls. This is what greatness looks like, this is what happens when you solve creative decisions creatively.

S: What advice would you have for someone looking to break into the industry?

J: I’m assuming you mean the tabletop industry rather than film as that is my focus now, so I would say first and foremost, excitement. If there is one thing I’ve noticed in my career is that anybody can become a good artist technically, it's not a superpower, but being passionate and excited for your craft and you’re ideas is, it's surprisingly rare. We live in a world where people waste so many hours on computer gaming and Netflix and still wonder when their big break is coming.

Every hour spent on a crap design or bad sculptor is an hour spent on becoming a better artist, learn to get excited about being annoyed at your abilities because that’s all the motivation you need to get past that and get better. A key thing that drives me, as bleak as it is, is never being satisfied. All I ever wanted to do was to be a conceptual designer on films, got there, wanted more. I wanted to make my dream gaming setup, achieved that and am already designing its follow-up to be vastly improved. I often wish I let myself enjoy the outcome of my creative labours more, but know that when I do I will drop down by 20% capacity. I have too many things to get done, and I’m so excited for the next Hagglethorn Hollow campaigns that I'll just have to wait till I retire to fully enjoy what I’ve built for myself.

"The only reason anyone in this world is good at anything is because they worked at it."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Every hour spent on a crap design or bad sculptor is an hour spent on becoming a better artist."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Really quite splendid. I can only congratulate Johnny Fraser-Allen on his stalwart fails in high school.

BTW, that ‘L’ in ‘Legend’ is grinding.

A great read and a similarly crap school time having teachers dislikes of eveything I did. hand skills was my strong points not wrighting down what I was doing. over the year’s I realised I struggled with things if I couldn’t understand then in my head for some reason I needed to learn in my head before doing the process to get the best results.

Awesome, what a great sculpter!

Great interview, inspiring work.

Great interview. love Johnny’s work. Had so many flash backs to being a youngster. I totally forgot I had owned that board game “the lost valley of the dinosaurs” Quickly went onto ebay to pick it up again so I can show my kids.

Love the Hagglethorn Hollow stuff and can’t wait to get my pledge at the end of the year. Should give me enough time to build a table to put them on.