How To Design One Shot Roleplay Sessions!

July 22, 2019 by crew

What do we mean by a “One Shot”. In essence, it is a roleplay game scenario that is not part of a larger campaign and is thus self-contained. Furthermore, it can also mean a scenario that can be played within the space of a single game session - so about four hours.

Therefore, designing a One Shot scenario requires a different way of thinking, but one which can benefit games masters with respect to designing scenarios for their long term campaigns.

Having A Clear Vision

Perhaps the most important aspect of a One Shot scenario is having a clear vision. What type of story should this scenario tell? Is it a rescue mission? Is it the investigation of a serial killer? Is it hunting down of some monstrous creature? One shot scenarios should have clear start and endpoints, and a clear conclusion. One Shots should also have more structure than most roleplay game sessions because you have a limited amount of time to play through the scenario. Structure helps with this by giving more guidance to the players.

A Sense Of Urgency

Whether it is a movie or an episode of a TV series, there has to be a sense of urgency. In the X-Files they are up against the clock to rescue someone, in Supernatural, they need to stop a ritual, and in movies, such as Event Horizon, they are racing to prepare the ship to escape the opening hole in space.

Urgency is also something you need to reinforce in a One Shot scenario. Every reveal of the plot within the story should lead to a rising sense of tension, and begin to accelerate the players to a conclusion.

The classic example is the Chronicles of Darkness scenario, The Terrible Tale Of James Magnus. The players are investigating the old house, and as the story progresses and they move from room to room, the frequency, and intensity of the ghostly manifestations increases. Each time, each room, reveals more about the ghosts and the plot, pushing the players to the heart of the house, and the final bloody showdown. Urgency suddenly becomes the growing need to escape - or to find the truth - in the case of this scenario.

What Are Your Goals?

Regular roleplay game campaigns, because of the benefit of time to explore such ideas, allow players to come in with less fully formed concepts of goals and aspirations for their characters. Again, the time restriction and limited scope of a one shot means you don’t have time to establish this. You need players to come in with clear objectives so that also means typically providing players with goals to pick from for each of their characters, or even providing a cast of pre-generated characters to use.

The latter option is useful for a multitude of reasons. Pre-generated characters allow you to have each character focus on a specific aspect of the story and rules of the game, and so give each player the opportunity to drive the story forward. Everyone gets the chance to be the centre of attention for the story. Furthermore, by using pre-generated characters, the inter-character drama is properly constructed in a way that also generates drama, but not to the extent that it hinders driving the main plot of the scenario forward.

Building The Structure

Taking the above on board, we can think about the structure of a scenario, so that it drives the story forward, generates a sense of urgency, fits the goals of the player characters, and also allows for the game to conclude within the allotted time frame.

Every scenario requires an “establishing shot” where we are introduced to the player characters, and at the end of which the plot of the scenario is introduced. This establishing shot is not always our cadre of characters meeting in a tavern or some space station meeting room. We can start a scenario “in media res” - in the middle of things - as explosions are rocking the ship, or a dragon is burning down the village. Using this manner of starting the scenario is also useful as it immediately sets the level of urgency. Are they running for their lives, or chasing the suspect?

Every scenario, of course, needs an end - the big set-piece - where the player characters face off against the final threat or challenge, and players take advantage of anything they have learnt or gained along the way.

This is important. In a one shot, you don’t have the benefit of time or scope to realign and refocus the players. You want to get to this conclusion. Which means you need to fail forward and create a sense of choice, while still coming to the same endpoint. Therefore running a one-shot is about getting to the end - but the players determine the “quality” of the ending they get.

With a start and end in place, the next scene we need is a “middle”. This scene is important for ramping up the urgency, signposting to the players where the plot actually is, and dividing the story into two key areas, “scene-setting and world-building” and “action, drama and conclusion”.

If we consider the pacing of all of the above, and that we have between three and four hours to play, we can break down our playtime into the following...

- Introduction and Establishing Scene - 30 mins

- Investigation and World Building - 30 mins

- Middle Scene, Refocus and Ramp Up Drama - 30 mins

- Action and Investigation - 30 mins

- Finale - 1 hour

We can see that this amounts to roughly five scenes. This is not a concrete rule and a game could consist of less or more (four to sevens scenes total) but the point is that we have some scenes we can bullet point and detail that are the obvious plot route, even if players dither, get distracted, or go after red herrings. You will note that for speed we also try to keep combat scenes/encounter down to one of two scenes, as combat can suck up a lot of time, and really only represent a few minutes of time within the setting. Bear in mind that you can shortcut combats that grow too long by having opponents give up or run away; not everyone needs to fight to the death. You can also run combats for a set number of turns with any hits on the final turn being the final blow.

Some Examples...

The Hunger Within uses the above structure. In the first scene, we are introduced to the characters as they arrive at the hotel, and we spend a couple of quick scenes for characters to engage in investigation and social interactions. There is ample chance through these scenes to expand upon the setting of the scenario, reveal plot and information, and also for players to come up with a working theory.

The middle scene then is a chance to act upon those theories, and follow other clues, while providing a “reveal” that signposts where the action is. This is a chance for players to feel rewarded for their well thought out theories, or for a dramatic twist. The nature of the setting also changes so that it is clear that while there are many routes, they will all lead to the same place - the conclusion.

Along that way, the additional scenes offer a chance for the players to perform further investigations and preparations that could benefit them in the finale.

The Terrible Tale Of James Magnus (found in Ghost Stories for Chronicles of Darkness) uses a different structure. The start and end are clear as the characters come to the haunted mansion and will confront the ghost (or flee) in the finale. But rather than scenes, the scenario is broken up into rooms. Each room investigated represents more time passing and the intensity of the haunting increasing. The middle of the scenario represents a rapid change of pace, as the haunting alter from simple ghost signs, sounds, and smells, to more aggressive, physical, and violent ghostly manifestations, with the attacks and clues drawing the players to the “heart” of the scenario - the room where the final reveal is made.

Now the above two examples have been made using Chronicles of Darkness as the basis. But the same ideas can be applied to Wrath & Glory, or Warhammer Fantasy Role-play, as these two games also rely on the usage of scenes. But what about more “map-based” games, like Dungeons & Dragons? How do we structure these one shots? Well, we do the same!

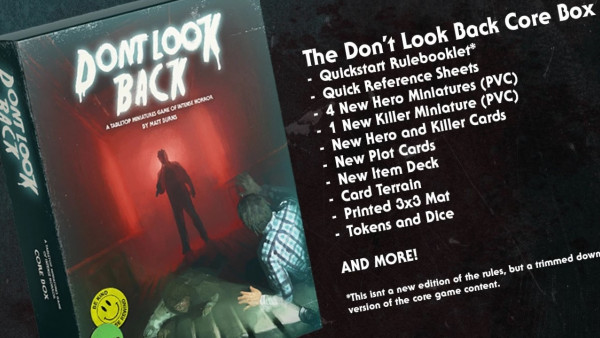

Maps, miniatures and grids are excellent tools, but also distractions and time sinks. So let’s reserve their usage for the finale.

For example, in the Iron Kingdom RPG, we can run a one shot where the players take the role of the Order of Illumination, who are witch hunters and are investigating a series of murders in the city of Corvis. Their trail leads them into the depths of the undercity, where they encounter gatormen and eventually the killer and his coven of witches. We can run this all with miniatures, but reserving their usage for the combat encounters where the rules for combat properly kick in. We can even use miniatures and a gaming grid to represent the movement through the maze of tunnels, as they investigate it, to give us a price paid for splitting the party, and using antagonists to take advantage of this. In a similar manner, we can do the same with Dungeons & Dragons.

Following these guidelines, we reckon you should be able to build some awesome one shot roleplaying sessions for the tabletop which should have your players hankering for more!

By Chris Handley & James Valadas-Marques - Darker Days Radio

What are some of your ideas, tips and tricks for building one shot roleplay sessions?

"One shot scenarios should have clear start and endpoints, and a clear conclusion..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"We can start a scenario as explosions are rocking the ship, or a dragon is burning down the village..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

And with one shots you can start with more powerful characters … so no need to be a lvl 1 wimp.

This works great for demos, because you get to see the good stuff.

It also allows you to do stuff without having to worry about surviving the episode, which makes it great for horror games.

And probably most important : keep it simple stupid.

Complex motivations don’t get a chance to shine in such a short timeframe.

And if it becomes a campaign … you can do what Hollywood/Comics do : retcon it

Excellent article. I especially like the part about timing the plot to fit in the single session. I find thinking of the adventure as a movie plot helpful to keep the proper story momentum going. Another point touched on that I want to reiterate is keeping the plot straight forward OR have backup plans to keep the action moving if the party gets stuck on a missed clue or decides to go off on a unproductive tangent. If you are playing in a one shot you should be prepared to have a bit less freedom than you would enjoy in… Read more »

interesting getting the action points from a show and setting them into the adventure can be a long and frustrating process may put many people off making large quests an great read but.

Really helpful and interesting article – will be taking on board a lot of these ideas!

great article, with points i’ll definately use while creating my liminal one shot

I only use miniatures for major combat encounters. It’s not just that combat takes time, setting up maps for each encounter can also be quite time consuming. There are ways to speed it up but for me using miniatures is purely for visual effect and so if I am using them then I want the environment to be as detailed as I can make it. So I might have one or two main encounters that I have preplanned with all the scenery and map tiles already set aside. But smaller encounters where maybe the players randomly find just one or… Read more »

What do people think about “leaving the door open”? By that I mean leaving the door open for a return to those characters in the future if the game is popular enough, so maybe leave a few unanswered questions at the end of the conclusion, questions that you don’t even need to have an answer to and that do not actually affect the conclusion.

I’ve done that before. I’ve run one shots which are effectively then developed into episodes of a TV show. So, each time these characters come to the tabletop they are given one shot adventures but with the option to come back and explore more.

It’s worked very well with Savage Worlds.

I actually like the idea of a series of unlinked one-shot sessions using the same characters, I don’t think there needs to be an overarching story arc linking everything together for a game to be fun.

Yeah, the only thing I use in common is obviously the same characters, maybe with a few new ones here and there dependant on players and an arch-villain who is always trying to thwart their Pulp adventure plans.

All the one shots I have written for publication often have sections at the end detailing “Where to go next” as often these one shots are also chronicle/campaign jump starts. In the case of The Terrible Tale of James Magnus I have run it as a pastiche of “Ghost Adventures” and so the ghost hunters, who before were just making crap up, now actually are ghost hunters for real. For the V5 demos I have written and run, again there are 2-3 different ideas at the end of the document describing what future scenarios you can run to get the… Read more »

Very cool 🙂