Behind The Board Games: Matt Leacock

March 14, 2019 by cassn

A man who requires no introduction, Matt Leacock is the game designer behind the board game classic Pandemic. Published in 2008, Pandemic has become a staple of the gamer's household and now has several expansions and legacy editions to its base game.

However, Matt Leacock is far from a one-hit wonder, and unique and interesting designs like the Forbidden collection, alongside stand-alone games such as Knit-Wit and Mole Rats In Space, have cemented Matt Leacock as one of the top industry leaders in game design. In this Interview, Cass sits down with this tabletop titan to discuss the success of Pandemic, creating a good game experience, and future releases from the designer.

Cass: When did you first know you wanted to become a games designer?

Matt: I’ve designed games as a kid and always dreamed of getting one published, but I never really dreamed of being a game designer (as a full-time profession) until recently. I never thought it’d be possible to do it for a living! It was a bit surreal to leave my day job so that I could design them every day.

C: All of your games have that rare combination of amazing mechanics, gripping narratives, quality components, and original artwork. However, what do you believe is most important when it comes to game development?

M: They have to be fun! Games can have beautiful, high-quality components and lovely artwork, but if they aren’t fun, they won’t get played. When it comes to design and development, ensuring that a game is fun isn’t easy or endlessly repeatable—it requires a lot of experimentation and research.

C: Obviously, we have to talk about Pandemic! It’s been your greatest success and launched your career. Was there ever a specific moment in the beginning which made you believe that Pandemic had the potential to become a household name in the gaming industry?

M: Not at all. I had no clue that the game would ever take off in the way it did. I think I was very fortunate—I had a good game at the right time with the right publisher. I have to give the publishers a lot of credit. They encouraged me to extend Pandemic into a whole line of games and helped field a talented team of illustrators and graphic designers. And I’ve partnered with several different co-designers on the Pandemic products, and they’ve all helped contribute ideas and expertise.

C: Tell us a bit about your design process. Where do you start when coming up with a board game like Pandemic?

M: I typically start in a notebook where I jot down the main concept and look at all the major elements that will come into play. Occasionally, I’ll draw a concept map—a collection of bubbles labelled with concepts (usually nouns) linked together with lines to form propositions.

Maps like this can be really handy when you’re trying to develop a system with a lot of relationships. But sketching like this doesn’t get me very far—I need to build a prototype. I try to build rough prototypes as early as possible—and keep them rough and flexible as I do lots of rapid experiments. During this first phase of design, I try to find a “core" game that will serve as the heart of the experience.

While this can be a lot of fun, it can also be very hit-or-miss. Many game ideas get abandoned at this stage because I haven’t been able to identify something that excites me enough. And it can be hard to come up with fresh, original ideas on a deadline. Sometimes it takes a while for them to mature; other times they just present themselves, as if they were there all along, just waiting to be discovered.

Once I have a core game that I’m excited about, I start a long process of iterative design where I refine the design, playtest it, analyze the results, and adapt the design, over and over, until the game takes shape. During this time, I take gradually take myself out of the playtesting process (become an observer rather than player) and as I do so, I also gradually increase the fidelity of the prototypes. This entire process typically takes about 6–12 months. Legacy games, however, can take much longer—up to two years or even more.

C: It’s very easy to focus on your career through the success of Pandemic, but were there ever any game prototypes that didn’t quite make it off the ground?

M: Yes, very many. I designed lots of games as a kid and several in college that I worked into full, polished prototypes. I printed two of them myself in small quantities: Borderlands (a fantasy card game) and Lunatix Loop (a racing game). I also had another game called Ants that I started working on before Pandemic and occasionally tinker with—that never seems to go anywhere.

C: Since Pandemic was released back in 2008, the industry has gone through significant changes regarding accessibility for creators through Kickstarter, public popularity, and financial backing. How do you feel the industry has developed since you first joined it, and where do you think it will go next?

M: The industry has grown tremendously since 2008. Back then, you’d see only a hundred or two games released at Spiel. Now, there are more than a thousand products featured there.

It’s now fairly straightforward to raise the capital you need, build an audience, and get a game published through Kickstarter. It’s a lot harder to produce a game that will see a second print run, however, since there is so much competition and so much focus on what’s new.

I really don’t know where the industry is headed although I’d be surprised if it continued to keep growing at this pace. I try to focus on what I can do well and chase what is fun and new to me rather than trying following what’s trendy.

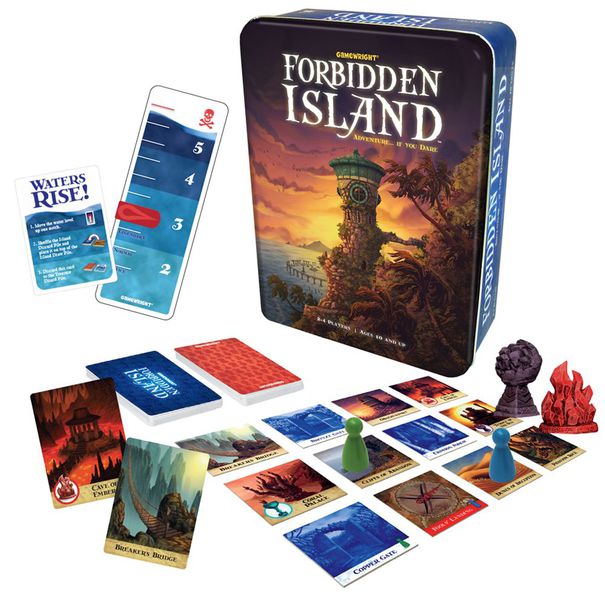

C: Let's talk about the Forbidden games series. These are three very different games with different components and different mechanics, yet somehow they seem to belong together as a collection. When you're designing a series like this, do you set out to provide some form of cohesiveness between games, or do you try to make each game independently?

M: We didn’t set out to create a series of games, but Forbidden Island was so popular that Gamewright approached me to do a sequel. After the success of Forbidden Desert, we thought about doing another. With each new title, I worked closely with the publisher to define the audience for the game.

With Forbidden Desert, we wanted to offer an even bigger challenge to players who liked Island. Forbidden Sky was designed to appeal with its different puzzle and toy factor. Each game has to do a different job and appeal in its own way—I don’t want people to think that one of the games will “replace” another one.

Designing lines of games can be fun because you can carry certain elements through the series. For example, all the Forbidden games feature a band of adventurers exploring a different terrain and the game tries to kill them in a different way.

They all feature tiles, an action-point-allowance system, are fully cooperative, and you can choose between four different actions each turn. By carrying over some elements from game-to-game, players can get up and running much faster. They can leverage their knowledge from the games they played before.

C: What advice would you give to others aspiring to break into the industry?

M: I usually tell designers to carefully consider their motivations—do they want to design multiple games or are they focused on getting one particular game published? That can help people determine whether they should slowly build a portfolio of designs before jumping into the world of self-publishing.

I think many designers want to get their baby published so badly that they jump in too quickly, without realizing that they’ll essentially need to start a small publishing business—and may find that they no longer have any time to design games anymore.

I also encourage people to network at conferences and ask a lot of dumb questions.

If they have a design that they’re trying to pitch, I encourage them to over-invest in the quality of the design by testing it early and often and to make sure they work blind testing into their process.

C: What are you currently playing?

M: I’ve been playing a lot of Magic Maze, El Dorado, Celestia, Decrypto, and Just One with family and friends.

C: What can we expect to see from Matt Leacock in 2019?

M: I have a new line of “roll and build” games premiering this August called Era. Each game is set in a different age. The first game, Era: Medieval Age has players competing to build the most prosperous medieval city and uses gorgeous, sculpted 3D pieces.

We can't wait for Matt's new games! What is your favourite Leacock design?

"Games can have beautiful, high-quality components and lovely artwork, but if they aren’t fun, they won’t get played!"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Upcoming game Era: Medieval Age has players competing to build the most prosperous medieval city!"

Supported by (Turn Off)

![TerrainFest 2024 Begins! Build Terrain With OnTableTop & Win A £300 Prize! [Extended!]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2024/10/TerrainFEST-2024-Social-Media-Post-Square-225-127.jpg)

Pandemic is one of those great sounding game’s I’ve not had a chance to play.

I can’t wait for Era. From the previews we’ve seen so far it looks like it’s going to be awesome.

Matt Leacock created some of my all time favourite games, games I have enjoyed playing for years and return to again and again… I am still cringing about how I completely didn’t realise this when I met him at Essen.

Pandemic is thé game I play with friends who are boardgame curious. The coöperative element is what makes the game so good. Most people have only ever played competitive boardgames.

I cannot recommend the Forbidden series of games enough – they really show off Matt’s skill as a designer. They’re all different, but easy to learn, but they have a level of strategic intensity to them that few games can pull off. One minute you’re co-op trying to get off an island with your friends, the next minute you’re surrounded by water and praying for a helicopter ride!!

I’m also really excited for the Era games. I’m not a huge Roll and Write fan, but if anyone is going to sway me it will be Matt Leacock!!