Behind The Board Games: Mark Latham, Designer Of The Elder Scrolls: Call To Arms

May 30, 2019 by dracs

Mark A. Latham is a writer, editor, history nerd, frustrated grunge singer and amateur baker from Staffordshire, UK. A recent immigrant to rural Nottinghamshire, he lives in a very old house (sadly not haunted), and is still regarded in the village as a foreigner. Formerly the editor of Games Workshop’s White Dwarf magazine, Mark still designs tabletop games (Chosen Men, The Walking Dead: All Out War, The Elder Scrolls: Call to Arms), as well as being an author of fantastical and macabre tales. His Apollonian Casefiles and Sherlock Holmes novels are published by Titan Books.

Visit Mark’s blog at thelostvictorian.blogspot.co.uk or follow him on Twitter @aLostVictorian.

Sam: How did you first get started in tabletop gaming? What were some of the early games that inspired you?

Mark: I started gaming really early on. I think it was the TV ad for Heroquest that really grabbed me. I played that game plus Space Crusade to death, and got heavily into tabletop RPGs about the same time.

I was always fascinated by miniatures, and my friends and I used to scour the blister racks at our local gaming store for models to use in our roleplaying games – I remember using minis and floor plans even when we didn’t need to, just because we loved them. That old store was not a welcoming place for youngsters (it was more a biker hangout than FLGS), so when Games Workshop opened a store in our home town, that’s when we really embraced wargaming. I still love Rogue Trader and 4th ed Warhammer to this day.

S: At one point you were the editor of White Dwarf Magazine. How did you come to find yourself in that job and what was your experience like?

M: It was such a crazy ride. When I was a kid reading White Dwarf, when Robin Dews was the editor, I literally decided I wanted to be the White Dwarf editor when I was older… I set out with that single-minded ambition! I worked part time at a GW store while I was at uni studying English. I applied for a job as a staff writer on Battle Games in Middle-earth (the LOTR part work by DeAgostini), and three years later I was the editor of that title.

When it came to the end of the run, White Dwarf was undergoing a massive revamp, completely changing the way it was designed, and centralising the team in the Design Studio so that there was no more ‘regional’ White Dwarf in each country. I went for the new Deputy Editor job working under Guy Haley and got that, then took over when he left, later becoming managing editor of White Dwarf and web content. I think I’m still the second or third longest-serving editor. It taught me a lot about managing deadlines and team working. It was simultaneously the most stressful and best job ever…

Image from My Comic Shop

S: What sort of stages go into setting out a monthly magazine like that? Was there a lot of different aspects to juggle, or did you usually have a unified idea of what you wanted in a specific issue?

M: I learned the ropes on a fortnightly part work, so the deadlines weren’t a problem. In fact, for the first time in White Dwarf history we went about three years without missing our deadlines. Tight ship, and all that. The main issues were working so far in advance of studio releases – we had to get multiple departments working in unison, and sign-off from all the head honchos well in advance. Once we had an issue plan, the guys in the White Dwarf Bunker were notorious for executing it come hell or high water.

Image from My Comic Shop

S: How did you go from editor to full time writer and games designer?

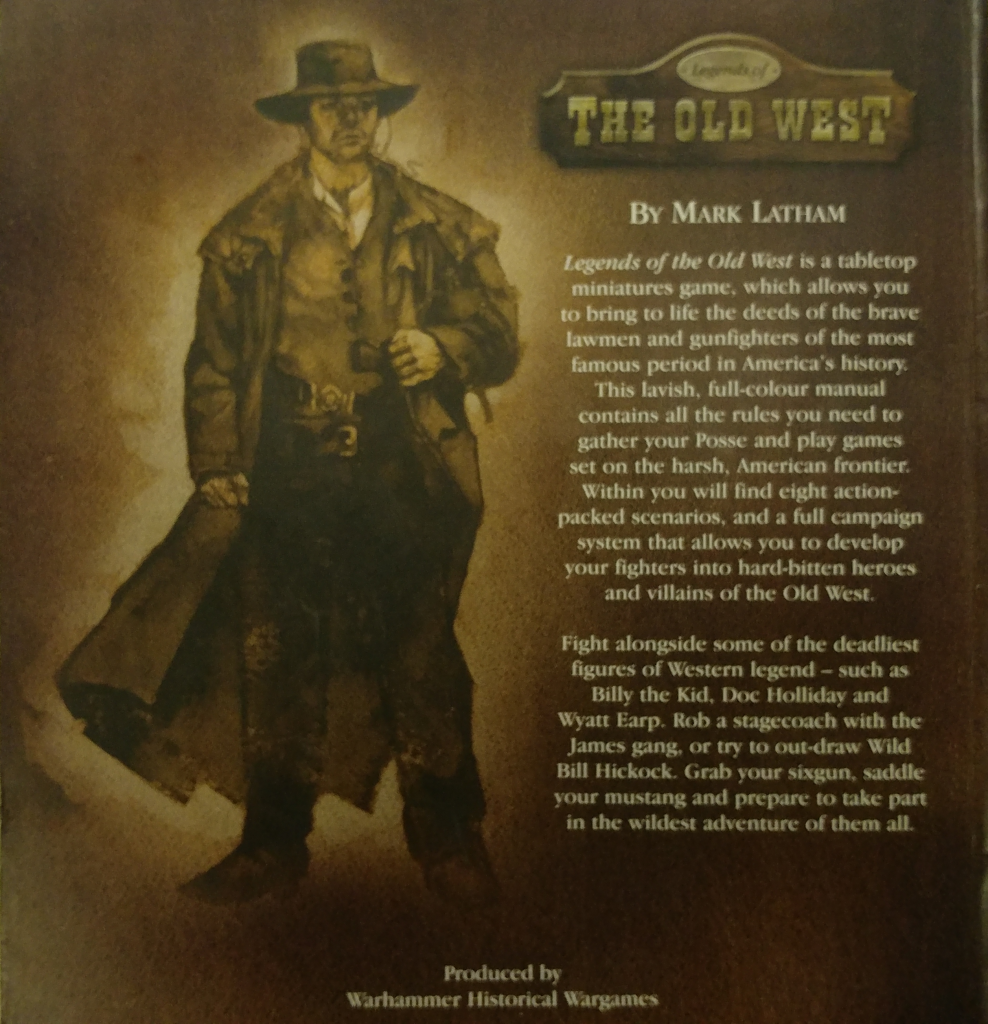

M: Ever since I was a kid I liked tinkering with game rules, and one of the first things I did when I started working at GW was chat to Rob Broom, head of the now-defunct Warhammer Historical. He gave me a crack at adapting a game for them freelance, called Legends of the Old West, and it really all spiraled from there.

I’ve been designing games alongside editing for my entire working life. I think what really took me to the next level was post-White Dwarf, when I moved to games dev. I was an editor, but I was working so closely with such a talented team, on so many projects… When you’re working every day with people like Jervis Johnson, it’s hard not to pick up some very useful tips and tricks!

S: You have worked on a lot of historical games, with titles like Chosen Men. What draws you to these historical periods?

M: I started with the Old West game purely out of personal interest. I absolutely love nineteenth century history, from matinee westerns to Sherlock Holmes books. I tried joining a few historical gaming clubs in my late teens, and was hugely put off by just how opaque the rules often were, and how hard it was to break into the community. So I set about trying to bring some cinematic flair to the games – Legends of the Old West is really the game of the movies rather than a historical simulation. Trafalgar is more ‘Master and Commander’ than ‘Signal, Close Action’. Waterloo was loosely based on the War of the Ring game, so it’s all about sweeping manoeuvres and grand strategies, and so on. I think I’ve developed my own style over the years – I like to innovate with specific game mechanics, but people generally know what kind of ‘feel’ they’re going to get from a Mark Latham game. I’m not done with historical games yet, so watch this space.

S: What is it like to work on an established IP like Harry Potter, or The Walking Dead when compared to coming up with a game from scratch? What sort of things do you have to keep in mind?

M: I always start from the top down, and ask myself what fans of the property will expect from the game. I tend to come up with a list of absolute ‘givens’, work out how the game should flow, and then retrofit mechanics to reflect those ideas. I was asked recently if there are any similarities in the way I approach novels and the way I approach games, and the answer was ‘yes’ – I’m telling a story either way, whether it’s a 300-page novel or a 90-minute game. Only when you know the story can you start the actual job of writing. You also have the licensing side of the project to consider – you can be as careful as you want in faithfully representing a licence on the tabletop, but there’ll always be some curveballs that you weren’t aware of. You have to be flexible when working on big licences – a games designer who’s too precious won’t last five minutes when a big movie studio starts reviewing their work!

S: Your latest title is of course The Elder Scrolls: Call to Arms from Modiphius. Did you have much of a history with the Elder Scrolls series before?

A long history! I recently did one of those ‘favourite video games’ lists on Twitter, and Skyrim is genuinely in my top three of all time. I’ve played every game in the series since Daggerfall, and it was me who bent Chris Birch’s ear for the lead design job. I was working with Modiphius already, and it just felt like fate that they’d acquired one of my favourite licences, so I couldn’t let that one get away. (It’s mine… My preciousss…)

S: The game uses the Fallout: Wasteland Warfare mechanics. Did these need much re-tweaking to fit with Elder Scrolls? What were some of the big things you had to change?

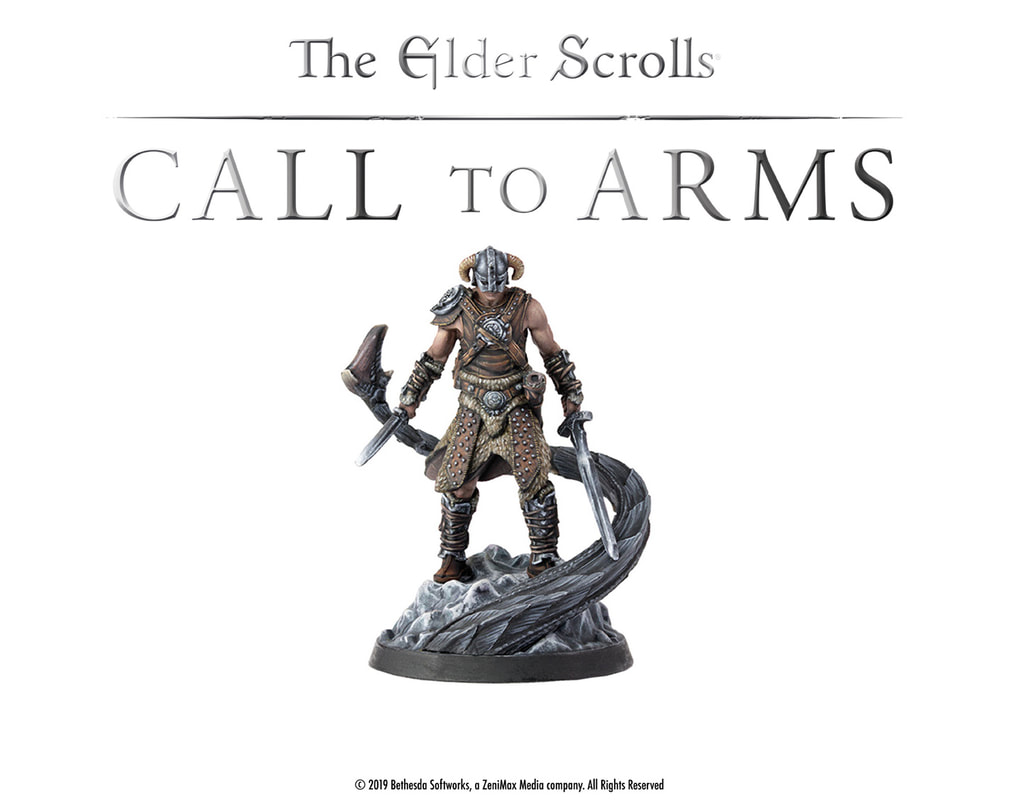

M: Players of F:WW will be familiar with the core Skill Test/Effect Dice mechanic, but a lot has been changed in the design process to accommodate the fantasy setting. Right off the bat, we wanted this idea of adventuring parties, with heroes leading their followers into monster-infested dungeons. So what we have is this system of customisable heroes, with a bunch of henchmen under their command, fighting each other while the wandering monsters of Tamriel ‘spawn’ around you and get stuck in! We’ve streamlined the searching mechanics, so players can hunt for magical items in treasure chests and immediately get stuck in using them. There’s a full magic and Dragon Shouts system, a simple ‘leveling up’ mechanic, lots of Perks… We could have just done a really simple re-skin I guess, but instead we’ve really gone to town so that fans of both franchises get a tailored experience.

S: What are the most important characteristics of Elder Scrolls you want to bring to the tabletop?

M: Tamriel is such a rich setting, with some really well defined and developed races, characters and factions. We wanted the factions of Tamriel to all feel different from each other, so Imperials play differently from Stormcloaks, and so on. But of course you can also play a party of Adventurers – small and elite, but individually more powerful than mere soldiers.

These guys need to have quests to achieve, and that feeling of being part of a wider narrative – this isn’t ‘just another wargame’, where you line up and fight. There are random events, enemies with their own AI behaviours, side-quests and narrative missions (we’ll be delving even further into narrative play with forthcoming supplements). And, of course, you can customise your heroes with a huge range of weapons, armour, amulets, and spells, because we all know a hero is only as good as their inventory, right?

S: If you could write for a game in any IP, setting, or time period, what would it be?

M: In terms of IP, I’ve pretty much got all the bases covered now I think! I worked all-too briefly on the Marvel Universe game, and I’d love another crack at that given half a chance. Other than that, I love games with dark, supernatural themes – some kind of Victorian occult skirmish or medieval horror would be right up my street.

Making a game like that commercially viable, however, is a challenge several publishers have found very tricky. One day…

S: What advice would you give to those who want to break into games design and writing themselves?

M: I think a lot of guys want instant success in this industry. Everyone thinks they can write a game, and lots of young hopefuls are willing to do it cheap, or free, which just leads to a flood of games on the market, not all of which are actually good. Some people think they can go on a course and then just start pitching board game ideas, which is notoriously difficult. My advice has always been to learn your craft, and spend time doing so. If I hadn’t spent fourteen years at Games Workshop learning from the best, I wouldn’t have half the skills I have now. Sure, I was lucky with some early successes, but if I wrote Legends of the Old West today, for example, it would be a very different game.

You don’t have to spend as long as me doing it, by the way – I took a fairly circuitous path into design - but the principle stands. So: play lots of games, get a job in the industry, be willing to work hard and even to start at the bottom. It’ll equip you not only with the technical skills you need, but also the team-working and time management skills required to be a successful freelancer.

"[White Dwarf] was simultaneously the most stressful and best job ever…"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"I’ve played every [Elder Scrolls] in the series since Daggerfall, and it was me who bent Chris Birch’s ear for the lead design job."

Supported by (Turn Off)

![TerrainFest 2024 Begins! Build Terrain With OnTableTop & Win A £300 Prize! [Extended!]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2024/10/TerrainFEST-2024-Social-Media-Post-Square-225-127.jpg)

I hope that The Elder Scrolls: A Call to Arms will have a lot less of the token/card overflow that Fallout: Wasteland Warfare has in my opinion.

Somehow I have missed all of his games… but I think… if Modiphius pushes the release to 2020 I can keep my “no new system this year” vow…. but he sort of shattered that on twitter…

HALP!

Always liked Mark and his approach to game design. It was a shame his tenure at WD was diring their “dick move” period as his work on BGiME showed his talents as an efitor.