Centennial Gaming In The Great War – The Campaigns Of 1918: Part Three

May 7, 2018 by oriskany

Thanks so much for coming back, Beasts of War history fans, to our continuing series on the 1918 campaigns of World War One. Specifically focusing on the spring and summer of 1918, Sven Desmet (BoW: @neves1789) and I are looking at gaming the 100th anniversaries of these battles, so vital to ending this “War to End all Wars.”

Read The Series Here

If you’re just joining us, in Part One we introduced the project and summarised the Great War up to this point, highlighting how some of the factors typical of the conflict can be brought to the tabletop. In Part Two we reviewed the “St. Michael” offensive, where the Imperial Germans made a massive push to win the war in early 1918.

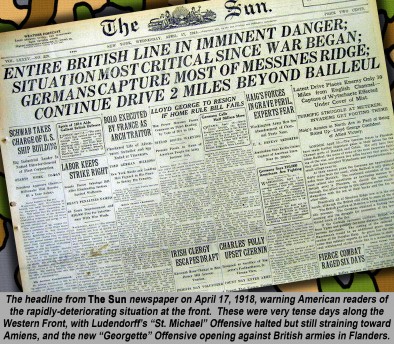

St. Michael was a gigantic, sixty-five-division offensive named for Germany’s patron saint. Hitting the British Third and Fifth Armies, it had actually smashed open the stalemate of the trenches. Yet the British had finally stopped the Germans (at horrific cost) at places like Villers-Bretonneux, short of their intended breakthrough at Amiens.

In stopping the Germans, the British had been greatly assisted by sizable French reinforcements from the south and British reserves from the north. It was these reserves concentrating against the German salient that concerned the German commander, General Erich Ludendorff, and would be the object of his next attack.

The Georgette Offensive

The Fourth Battle Of Ypres

Ludendorff’s second massive hammer-punch of 1918 would be called the “Georgette Offensive.” As more and more British reserves were pulled into the Amiens sector to contain St. Michael, it was hoped that other British armies further north were be left without adequate support, and thus vulnerable to attack.

The Georgette Offensive would strike through Flanders, hitting the British First and Second Armies, along with the Belgian Army holding the extreme northern end of the Western Front. There were even Portuguese divisions in place. Most of these Allied formations, though, were badly understrength.

Georgette would see Ludendorff hit this line with forty-six divisions from the German Fourth and Sixth Armies. The attack opened on 9th April 1918, just as St. Michael was slowing down near Amiens, and as Allied reserves were leaving Flanders to reinforce Amiens.

The German plan was to open a breakthrough, then pivot northwest toward the Channel coast to take port cities like Boulogne and Calais. If this is starting to sound like “Dunkirk - The Prequel,” you’re dead right. But this kind of manoeuvre is much tougher to do when you have no panzer divisions in your spearhead.

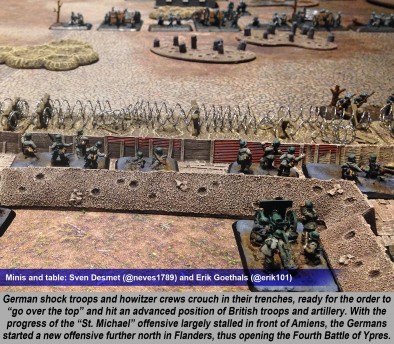

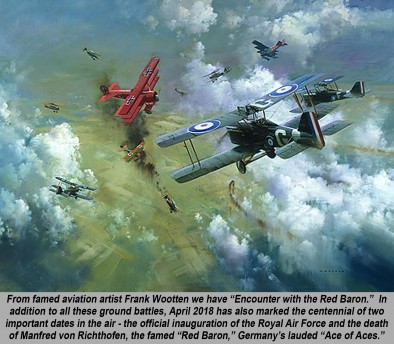

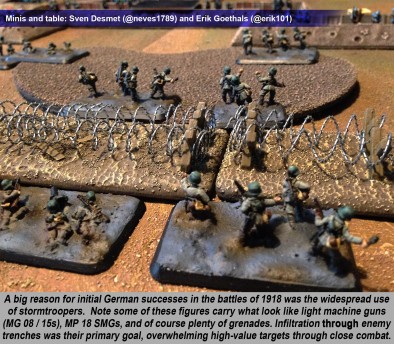

What the Germans did have, however, were stosstruppen, their elite shock troops or “stormtroopers.” Thus, initial German progress was again bloody but brisk, with the British even losing Passchendaele Ridge for which they’d spilt a generation’s worth of blood for in earlier years.

But would the Germans make that breakthrough, complete that encirclement, pin the northern Allied wing against the Channel coast? Everything depended on whether the British and Belgians would hold along the Flanders line.

Sven Takes The Field

“Do Or Die”

As has been discussed earlier, the Spring Offensives were a strategic do or die for the German Army at this point. Operation Michael had ground to a halt in front of Amiens, thus Operation Georgette was launched to maintain the offensive momentum and keep the Allies on the back foot.

One of the main objectives, besides reaching the Channel ports, was the small town of Ypres. This little-known Belgian town had been the centre of several major engagements and by the time Georgette launched, people were talking of the Fourth Battle of Ypres. Four battles in as many years means this place has some importance, right?

Why Ypres?

The First Battle of Ypres had come in 1914 when the Germans tried to take the town during the “Race for the Sea” but were repelled by the British, Belgians and French marines. Most of the fighting had taken place in the last piece of unoccupied Belgium, north of Ypres in the area between the North Sea and the town itself.

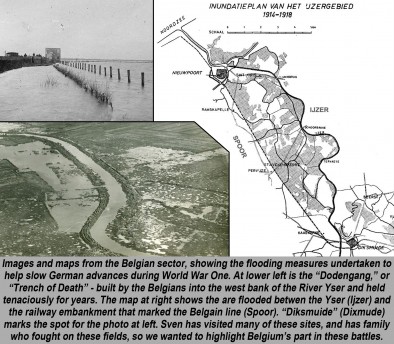

King Albert I, Supreme Commander of the Belgian forces, recognised the gravity of the situation. His forces were depleted and had their backs against the wall, the distance between Ypres and the French border only being fifteen kilometres. To prevent any further German advances, a “scorched earth” policy was put into action.

The plain between the river Yser and an almost parallel rail embankment was flooded. In practical terms, this would put a large body of water between the Belgian and German frontlines and make the entire area north of Ypres almost impassable. Only with the Hundred Days Offensive would this area of the front see major action again.

The Second Battle of Ypres (spring, 1915) saw the Germans try to break the resistance around the town with the first mass gas attack. The town was an ideal target as it was the furthest to the German right (being denied the Yser plain) and was situated on lower ground than the German's own positions near Passchendaele.

The Canadians bravely held their positions and prevented the Germans from capturing the town. The sector would then stay relatively quiet until 1917 when Field-Marshal Douglas Haig tried for the small ridges overlooking Ypres and a breakthrough to the Roulers rail hub. This Third Battle of Ypres is also known as the Battle of Passchendaele.

Despite the great loss in life, the Battle of Passchendaele did not provide the breakthrough that was hoped for. Ypres had by that time become more than a strategic position, it became a symbol of British doggedness to hold fast. This would in turn only increase its strategic value for a new German offensive in 1918.

The Battle Of The Lys/Fourth Battle Of Ypres

Now in 1918, a breakthrough at Ypres would threaten the Channel ports and see the entire Belgian position and British First Army outflanked. Operation Michael had already proven that large advances could be made and many German troops felt the “do or die” nature of the offensive.

The Ypres sector had gone quiet shortly after the Battle of Passchendaele. The British First Army under Horne had been posted south of town but was in rough shape and recovering from 1917 battles. Among them were two Portuguese divisions who, just like their British allies, were in bad shape.

To the north and occupying the town itself was British Second Army under Plumer. During March they had slowly begun to make preparations to fall back from the Passchendaele ridge and shorten the front. After Georgette kicked off, it would take the German Fourth Army a week to figure out that the British were no longer actually there.

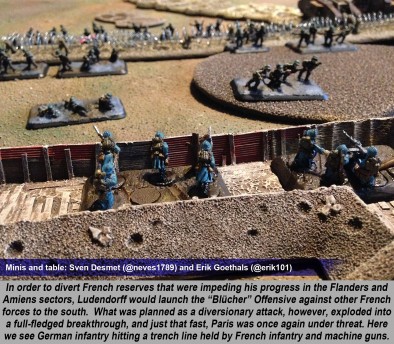

On 7th April 1918, the offensive began with a barrage (following the Bruchmüller recipe) that lasted until the morning of 9th April when the Stoßtruppen went over the top. In the south, the German Sixth Army outnumbered the British First Army almost three to one and thus quickly broke through the lines.

A number of British and a Portuguese division had to withdraw and by the end of the first day, the Germans had penetrated the line eight kilometres deep over a front fifteen kilometres wide. The stormtrooper methods were proven yet again to be successful, however they also greatly outnumbered their opponent thus giving them a false sense of superiority.

By 13th April British, Australian and French divisions were quickly brought up to plug some of these gaps. Field-Marshal Haig also issued his famous “backs to the wall” order, realising he only needed to hold on until the German offensive ran out of steam as it had done a month earlier.

On 17th April, the German Fourth Army moved forward towards Ypres. To the north of the town, it encountered stiff resistance from the Belgian Army near the village of Merkem. There the Belgians fought their hardest battle since 1914 and managed to repel the Germans, capturing over 700. The strategic point between the flooded area and Ypres had held.

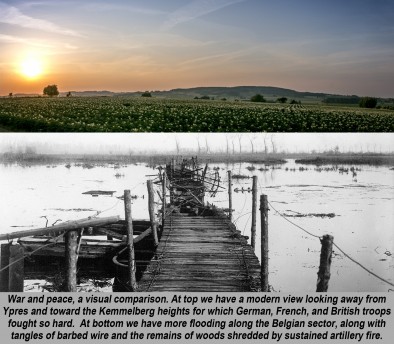

The main thrust of the Fourth Army however came near a hill named Kemmelberg, dominating the region between Ypres and Armentières and provided an excellent vantage point for artillery spotting. It was one of the only major hills in the region worthy of the name and was not coincidentally at the centre of the German attack.

The first attack up the hill was repulsed by the determined British troops under Plumer. They were relieved by a French division who subsequently got attacked by three German divisions. This second attack succeeded, giving the Germans the hill that had thwarted them for four years. It would remain in their hands until the Hundred Days Offensive.

By the time the Kemmelberg was taken, the offensive had reached the end of its third week and had run out of steam. On 29th April Ludendorff called off Operation Georgette. Much like the Third Battle of Ypres, the Fourth Battle saw the attacker advancing less than twenty kilometres and only taking a tactical height but failing to score a strategic victory.

Both sides had suffered over 100,000 casualties. As with Operation Michael, true breakthroughs and the return to manoeuvre warfare had not been achieved. When viewed in that light, these operations were just as costly in human life and as much part of the learning curve to achieve a breakthrough as battles like the Somme and Verdun had been.

For Germany, the failure of both Michael and Georgette were a strategic loss. Not only had they not achieved their objectives, but a large portion of their best soldiers had become casualties. They would not have the time, resources, morale, or political support to recover whereas the Allies, thanks to American support, were only getting stronger.

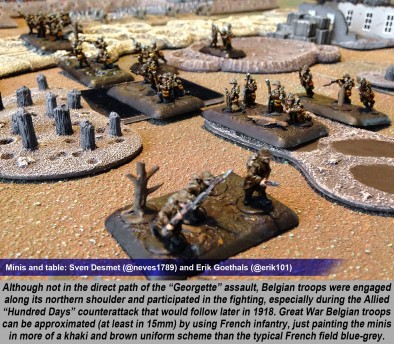

When it comes to gaming, Operation Georgette offers some great opportunities. For example, the use of Belgian troops, which can be easily represented by painting French troops in khaki colours as both Belgians and French soldiers wore the famous Adrian helmet. It's one of the first engagements after 1914 where they go toe to toe with the German army rather than skirmishing in the flooded area.

Another opportunity lies in an uphill battle, representing the fighting for the Kemmelberg. Here you can use either the French or British to face off against your Germans. In any case, as with Operation Michael, Georgette offers enough inspiration to build, paint and game in true World War One fashion.

Oriskany’s Debrief

In all, the Georgette Offensive wreaked tremendous damage on the British and Belgian Armies in Flanders, but did not produce the decisive breakthrough that the Germans wanted toward the Channel coast. Even worse, the Germans had suffered some 330,000 casualties in St. Michael and Georgette and had no replacements for them.

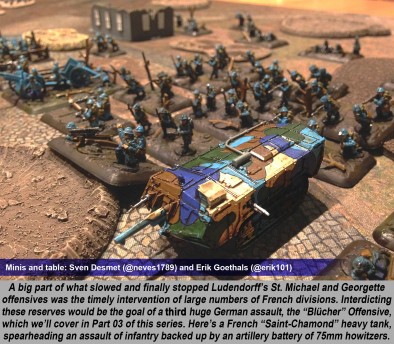

Meanwhile, the French were continuing to send reinforcements from sectors further south. To stem this shift of reserves, Ludendorff resolved to give the French something else to worry about. He’d launch a third offensive in the south, along the Aisne River, toward the Marne River and possibly even Paris.

Come back next week when we see the French and even the Americans take their share of Ludendorff’s fury. The American Army earns a few stripes, and the United States Marine Corps gives birth to a legend at a place history will remember forever as “Belleau Wood.”

Meanwhile, please post your comments, questions, and feedback in the comments below. We know there are some World War One aficionados out there...

...so get out of that trench and tell us what you think!

"...Ludendorff’s second massive hammer-punch of 1918 would be called the “Georgette Offensive""

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"... as with Operation Michael, Georgette offers enough inspiration to build, paint and game in true World War One fashion"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Great read. From all that I’ve read I have never quite understood why the Germans didn’t manage to take advantage of the gas attack at Ypres in 1915. Personally along the the French mutiny in 1917 ( still ring it hard to believe they didn’t know about it) as it was one of the few moments in the war the Germans had of winning the war

Thanks very much for getting us started, @torros ! 😀

Interesting points on when Germany really could have or couldn’t have won the war. I always maintain that the true “turning point” of a given conflict comes long before most people think it does, so I certainly would not argue with these earlier dates.

Would you characterize the 1914 Offensives as a chance for Germany to win the war in the West, or did they just have too far to move without sufficient mechanization?

I think there was a lot of tinkering of the plan by Moltke which led to the weakening of the hook into Belgium as he added to the strength of the German army on the Frontiers. As I mentioned before the Frontiers armies not carrying out the plan didn’t help. I wonder though if the biggest problem was the Russian army only taking 6 weeks to mobilise and advancing whereas the Germans expected them to take from memory 10-12 weeks which led to even more divisions being withdrawn from the attack on the West

I see what you’re saying regarding the alteration of the plan, shifting more and more formations from the right (where the power was supposed to be) to the left. I’m also reading where the main target if the original plan was supposed to be west and south of Paris, not directly at Paris itself. Although such a vast encircling “kesselschlacht” encompassing virtually all of Belgium and northeastern France, including Allied forces presumably trapped in the “bait” territory of the Alsace-Loraine, seems a little far fetched for an army with the technology and mechanization of the 1900-1920s. So who knows if… Read more »

As for the Mutiny it’s impact and reason for happening has been extremely exaggerated over the years. The Mutiny wasn’t about the French Soldier not wanting to fight it was about them not wanting to get involved in suicidal offensives and not getting much leave. The French were willing to fight defensively they just didn’t want to go over the top and run into machine gun fire. The reason they (German’s) didn’t know about it is that it wasn’t a huge affair. The French didn’t raise any flags, sing revolutionary songs or throw down their rifles they just sat in… Read more »

From what I understand, although the Mutiny was pretty widespread … like you say, the French soldier didn’t throw down his rifle and go home, they just refused to be butchered in further ill-planned attacks. Telling evidence for the relatively sympathetic and benign nature of the mutinies can be taken from how few courts-martial proceedings were carried out, much less death sentences passed down and far fewer even carried out – actually resulted, especially in relation to the number of troops in the effected units. Another “circumstantial indicator” is the reforms and concessions Petain enacted in the aftermath to restore… Read more »

There is a fabulous movie dealing with this issue, “Paths to Glory” with Kirk Douglas as Colonel Dax. The mutiny seems to have been used just to save the face of certain ruthless commanders, who even ordered their artillery to hammer a barrage on their own trenches.

I’ve seen clips from that movie, @jemmy and read somewhere that the female singer in that movie was actually German and later became the director’s wife (Stanley Kubrick, who’d later do Full Metal Jacket). I don’t think I’ve seen the whole thing.

I never heard about intentional French shelling of their own trenches. Was this to get men to leave them? To prevent their return after a failed attack? Straight out punishment for perceived failure?

Indeed, so it was. The French soldiers were ordered to leave the trenches and attack, due to massive German MG-fire however they were mowed down in the moment of leaving the trenches. The French commanding general then ordered the own trenches shelled in order to make them carry out the attack. An artillery officer, however, refused to carry out the order without wriiten notice, so the actual shelling didn´t take place on a grand scale. Later, when asked, this general said the soldiers had been mutineers and cowards, because if they hadn´t been, their dead bodies would lie around on… Read more »

An insane episode. I’d never heard of it – but you learn something new every day on BoW. 😀 Thanks @jemmy !

Hope you guys like part three as much as part one and two 😀

For those interested, we continue the discussion in our forum topic:

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/centennial-gaming-in-the-great-war-springsummer-1918/

Indeed, that support forum is doing very well, with some really great insights presented by many of our historical community members. 😀

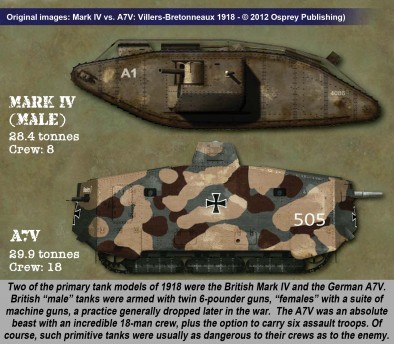

Another great article! Great to see a little of the Belgian perspective. And the variety of weapons is also great to see in an image, rather than a list of statistics and numbers.

Thanks very much, @pslemon ~ yeah, @neves1789 did a great job with that part of the writing. As for the weapon images, I just tried to collect images of the most relevant weapons (by no means are these lists inclusive) and scale them together into an informative, high-level reference. This way people who are perhaps interested in building WW1 armies have a quick guide they can start to go on. Scaling on these kinds of image compositing is surprisingly tough to get right. The trick I used for these images was to match up the trigger / trigger guard assemblies.… Read more »

Great read @neves1789 and @oriskany. While I am familiar with the Michael offensive, I am not with the Georgette offensive so it was great to read about the efforts of Belgium. As the Germans approached Amiens another factor came to our aid and further slowed the German advance. They Germans began to overrun some of the massive supply depots. These were filled with much food stuffs that had not been seen in Germany since the blockage had started to take effect. Then there was a huge amount of alcohol that was consumed. A storm trooper with a full stomach is… Read more »

The stopping to loot seemed to occur in all the German offensives. There was a German soldier who was interviewed on the BBC The Great War series mentions that the Germans couldn’t believe how well supplied the Allied troops were compared to themselves and their families at home and that the looted goods gave them more and better food than they had in 3 years

Too true @torros. I have read and seen documentaries that say very similar things.

I’ve found one quote from a postal censorship office about the quality of food and supply in the German Army, at home, and as a prisoner in an American POW camp:

“Prisoners of war under American jurisdiction continue to send home glowing reports of good treatment. It is clearly deducible that they are more satisfied with their present condition, than they would be at home”

—Postal Censorship, April 12, 1919

Better food and treatment as a POW, then back in your own lines or even back in your home town. Indeed things were very bad.

Awesome, @jamesevans140 – I did not know about these discipline problems in the German stormtroopers. We do make the case later on Part 05 on the German soldier “coming to the end of this rope” after four years of war, the threat of Bolshevik uprisings at home, starvation and privation and blockade at home, four years of casualties, and oh look, a whole new fresh army in the form of the Americans.

But specific episodes like this with the stormtroopers I did not know. Thanks for the heads up! 😀

Thanks, @torros – in regards to the blockade and conditions in Germany and in the German Army, I’m reminded of two things: 1) I always find it interesting to consider how perhaps these conditions (brought about by a British blockade) may have been used to justify the U-boat war, especially when it progressed into later years and more and more restrictions were lifted. Is what we are doing somehow wrong? No more so than what the British are doing to OUR families … 2) I also recall the mixed outcome of Jutland, which Scheer and the German Navy liked to… Read more »

Jutland is the battle that ultimately failed to deliver a vision. It was in the cold light of History a critical point in the War. It helped the Allies win by maintaining the blockade of Germany It therefore was a strategic victory for the Allies. On the day the Royal Navy lost more ships and Men but they started out with more ships and men. The problem was Beatty who thought he was the modern day Nelson and wanted glory, it was his battlecruisers that were taken out because of the shortcuts in safety taken as a result of the… Read more »

I would agree with the characterizations of Beatty and Jellicoe. As I am totally sure you’ve read, Jellicoe was often seen (rightly or wrongly) as the “one man who could lose the war in an afternoon” … i.e., the man with all the responsibility, while Beatty was the “battlecruiser maverick.” All speed, all guns, no armor … almost like the man himself (to stretch the metaphor a little – all dash, all aggression, none of the weighty responsibility of Jellicoe). Yet Jellicoe winds up taking the blame for Jutland not even being a defeat, just not a big enough victory.… Read more »

Had a great two part battle over the weekend with a British Tank assault on German lines. Two Tanks made it to the German lines with out breaking down. The second break through mission was to the town beyond. Unfortunately for the British their tanks got held up on a river crossing and the infantry couldn’t take the town. In 2014 we did a 1914 battle and it was interesting to go from cavalry to tanks. Next year doing something war of independence related.

Awesome, @denizen ! 😀 I don’t suppose you had any photos of your game? If so, we’d love to see them in our Great War Centennial forum topic:

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/centennial-gaming-in-the-great-war-springsummer-1918/

A good interesting read Ypres was difficult for many of the British troops to pronounce so they started to call the town wiper’s to each other Guy’s.

I won’t lie, before our recent interview on the Weekender I pinged a few language sites and You Tube for pointers on pronouncing some of these towns and rivers. Even then I’m not sure I got them right, because I got multiple results for the same name. 😐

I think theirs some other town that were renamed during both war’s by troops from different country’s.

If not renamed, then mispronounced so may times that the town somehow gets a new pronunciation, at least in the home country of the troops who were there.

e.g., how many times have we seen the American mispronunciation of “Bastogne?” Here’s a hint, it’s not pronounced here in the US the same way it is by the people who live there in southern Belgium.

Or my favourite Waterloo. ..

Are we saying Waterloo incorrectly?

Well, you can look at this like this: If anybody criticizes you for wrong pronunciation, bear in mind they understood what you meant. Otherwise it wouldn´t have been possible to find the fault. As long as one´s being understood, everything´s ok.

However, I would really like to know how Bastogne is pronounced in the US…

Or Lord, I’ve heard:

“Bast-OINE”

“Bast-OG-nee”

“Bast-OWN.”

“Bast-ERN”

Bas ton ya

Was one of my favorites from a British documentary.

Too true, @jamesevans140 – I used to wonder how producers could be so inconsistent with the pronunciation of these Belgian towns and cities. Then, in preparation for the Weekender interview, I tried some YouTube “research” on how to pronounce Ypres, and got three different sounds in three different videos. 🙁

I have a suggestion. Three syllables:

1. “Bas” say it like “bus” (the vehicle)

2. “to(n)” say it like “ton”

3. “gne” say it like “ye” like in “I love ye, me highland lad!”

I think with this you can trump them all: “Bus – ton – ye”.

Awesome, @jemmy – with the emphasis on the middle syllable?

i.e.,

bus TON ye

??

I love those early tank designs – they look like something out of a Doctor Suess book. 😀

Can’t argue with that. 😀

All Very 30/40 design book for new tank’s?.

Earlier generations of tank design were far more varied than they are today. As the decades progressed, battlefield evolution quickly weeded out the designs that did not work, leaving fewer and fewer designs ideas that DID work – steadily refining the overall concepts of tank design to a narrower and narrower range of “apex” features.

It was the same in the 70/80s with some stance unusual design’s.

The development of the tank is often described as Darwinism on steroids.

Some of the silliest ideas for tank designs in the 1970s and 80s are (in my opinion) the insistence of the Americans on the obsolescence of the actual high-velocity antitank gun, instead insisting on the 152mm guided “Shillelagh” missile as seen on the M551 Sheridan. It got so bad that this crashed the joint US-West German XMBT-70 project, with the Germans persisting with their 120mm Rheinmetall and the Americans sticking with their missile. So they went their separate ways, the Germans wound up with the Leopard 2, and the Americans (after failing to make the missile work very well), wound… Read more »

The Sheridan looks a great idea like a remade of the UK scorpion to air dropped in assault tank.

Aluminium still looks silver when molten I remember that from collage plus look at the ships in the Falklands war burning not good.

Yep, HMS Sheffield. 🙁

Damn, you reading through this did keep me up too late on a work day 😉

Yeah, these articles are a little long. Trust me, they were edited down from much longer, but we make sure to keep within the publication parameters of the site. There’s a lot to cover, though, and we did wind up with 14 images in this one rather than the usual 10-12. 😀

I am not complaining – other that as a fool I started reading after midnight and had to be up at 6am ….

if you’re having trouble sleeping, just read my parts over and over again. One of my introductory paragraphs and a glass of warm milk will have you out like a light in 30 seconds flat. 😀

Yesterday I was locked down in a communication trench (or what we superheroes call website access problems, thanks to BoW Tom for fixing it), so my comment today. Another part not just to read, but to wolf down vociferously. Great and informative. The picture with the newspaper really has me. I wish I had a copy of this one to peruse and of course to savor the smell of old victorian paper. Seems the British were panicking and furthermore it shows the British were aware and thought it possible the Germans were finally launching the possibly decicive and victorious offensive… Read more »

Yes @oriskany the Germans had an issue with discipline, but I think it goes even deeper than that. The Royal Navy’s blockade was now biting at its deepest. People were starving to death back in Germany while priority was given to meager rations on the front. Even the rations were more about filling rather than nutrition. So when these slowly starving men encountered the supply depots the survival part of human nature evaporated discipline. The stosstroopen were disliked by their brothers-in-arms as well. The rest of the army resented that they got marginally better rations and when the stosstroopen were… Read more »

Thanks, @jamesevans140 – You see the same kind of resent building up among the “landser” grunts in World War II with the Waffen SS or even certain Wehrmacht branches such as panzer troops.

Totally agree @oriskany. When there is not enough food and basics to go round, any group that gets more or better than the rest there is going to be resentment.

After Hurricane Katrina basically wiped New Orleans off the map in 2005, federal assistance and disaster management officials were appalled at the complete breakdown of law, order, or basic civilization. Take away people’s food, air conditioning, running water, internet …

Afterwards there were a lot of lectures, books, essays, etc. I always remember what one said:

“We are nine meals away from anarchy.”

I think that it is very true.

With cities such as they are, accounting for an increasing majority of our population and a complete reliance on complex, computer-driven logistical networks for power, clean water, food, sewage … knock out the electrical grid for a major metropolitan city, prevent evacuation, and leave it cook for a while … then watch as they play “Dark Ages” at 1:1 scale. 🙁

If i recall in ‘The Western Front’ Richard Holmes mentioned that during the 1917 mutinies French units arrived at their form up points having deliberately not brought their Rifles!

A great tv series too by him and well worth investigating via ‘the tube’ if anyone is interested in the changing nature of warfare 1914-18 from one of its very best historians..

The quiet rebellion of 1917 was the Australians. All of our officers had to be with a British officer who would, shall I say advise us because we did not know any better. The British of the day could not come to terms with Australian discipline. They always assumed we were third rate and had to be pushed, otherwise we might run away if no one was looking. It started out o.k. they would assign a major to supervise one of our majors. As British officer casualties piled up we had 1st lieutenants fresh out of school lording it over… Read more »

I remember talking to a chap at the War memorial in Melbourne and he was telling me that quite a few Australian troublemakers quietly disappeared after discipline problems were sorted out internally within the battalion without the higher ups getting wind of a problem that might have happened

I have run across material where families in Britain even today are trying to get their family members’ names cleared, 17 and 18-year old boys wrongfully shot for cowardice and desertion simply because “an example had to be made.”

Great info, @torros – of course we never killed anyone, but back in my time in, when there was a troublemaker afoot, the quiet line was usually: “we don’t need to get the officers involved in this, do we?” It’s embarrassing for the platoon / shop / whatever.

“Aisle Five” was the place in every warehouse where problems within the enlisted ranks were sorted “off the books.”

Yes it’s still a sensitive issue over here although I think they were all pardoned about 10 years ago

This is an interesting article

http://www.diggerhistory.info/pages-discipline/details.htm

That’s actually good news about the pardons. I’m sure the document I was reading was old, it was a .pdf scan of an article from a military history magazine, God knows when or which one …didn’t catch the date but you could tell it was pretty old (1990s at the latest)

The other issue was what was not considered a discipline in the Australian Army was a major issue to other armies. Back home before moving out a guy may promise someone’s mother that he would take good care of her son because he was a mate and she had nothing to worry about. To many guys this was a promise that had to be honoured. So when this mate got badly wounded he would follow him back all the way to England or until he believed his mate was getting proper care and would be all right. Then he would… Read more »

I meant mad mob but my kindle decided otherwise.

Interesting perspective on the Australian soldiers going back with their mates to ensure they are taken care of. I’m not 100% sure I agree, but then again I’m probably looking at the issue through the lens of more modern battlefield medical care and CASEVAC procedures. Those probably weren’t in place in 1914-18, so the context of the Australian conduct would admittedly be different. In a more conventional setting, I would argue that in keeping his promise to his friend and friends’ family by accompanying him back to the rear to ensure he gets correct care … he’s breaking promises to… Read more »

To true @oriskany, the past is another country and they do things differently there. This practice was unique up to the end of WW1. I am talking very generally now. If you were wounded back then you could lay were you fell for hours or even days in some cases. So our practice of making sure your mate is alright was more like a back then attempt at medivac, given the over worked primitive system of the day. Back in this time the section our platoon reacted differently. If Jacko took one then as mates we have to look after… Read more »

Most of the men in his unit would of come from the same district back home with many of them growing up together. This has always been an interesting dynamic to me, the benefits and drawbacks of this kind of “regional” or “local” recruiting. In America, we definitely do NOT do this anymore. But they certainly used to. The ACW has some of the most vibrant stories of this, where men wouldn’t run because the others in their company were friends and neighbors from back home. There are the sad stories of the British “Pals Battalions” that were so badly… Read more »