Enough Of The Charades – It’s Time For A New Concept In Gaming

September 13, 2018 by ludicryan

“OH! SHEEP!?!”

“YES OF COURSE IT’S SHEEP! NOW WHAT’S THE CONNECTION WITH SCIENCE?”

“OH, CLONING!?”

“YASSSSSS!!!”

You might be forgiven for thinking you’ve stumbled into another Settlers of Catan retrospective but this happens to be a regular exchange between players of Concept: a game from Alain Rivollet and Gaëtan Beaujannot. Much as the woollen quadruped graces many of our tabletop adventures, its presence here is not because of game components but through the communicative considerations of the player.

What might initially turn you away from Concept is its similarity to other, more standard games that your non-board gaming family might force upon you at Christmas: like Charades and Articulate. But Concept is much more than those simple word games: it is the epitome of this subgenre that helped pave the way for popular titles such as Codenames, earning its 2014 Spiel des Jahres nomination along the way.

Playability

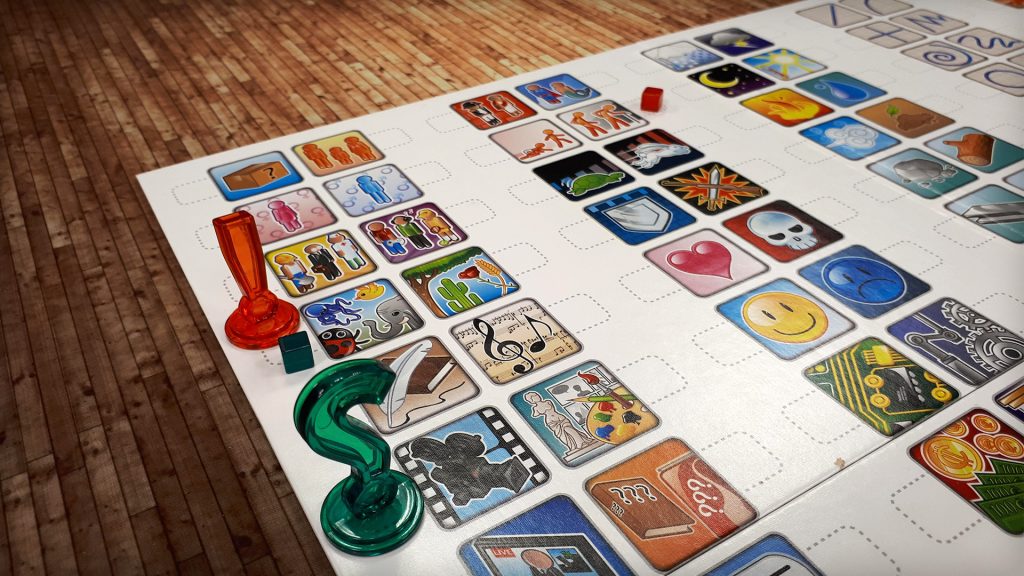

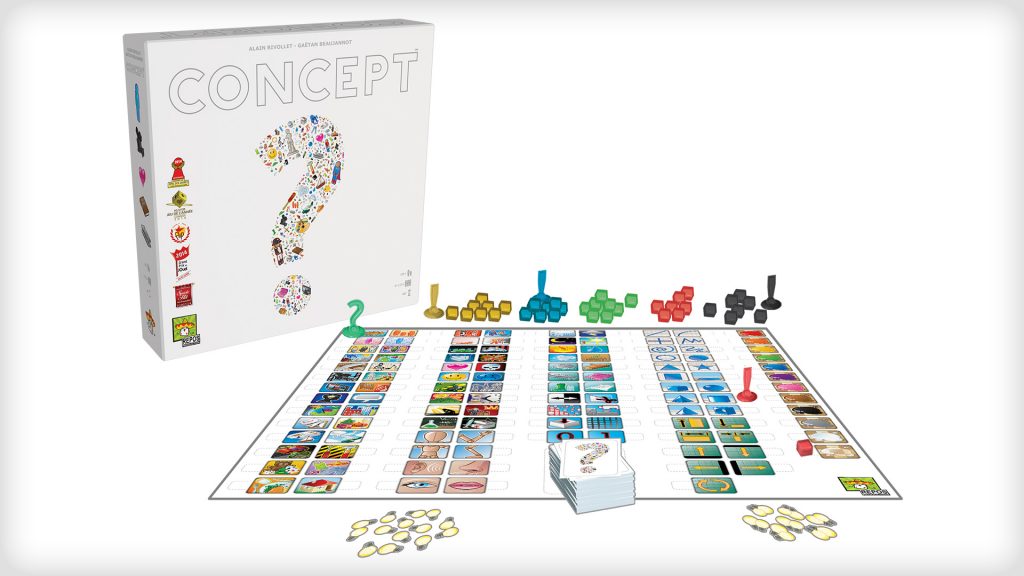

For most, the format of Concept is familiar: try to communicate a certain thing without directly saying what it is. Where the innovation in this game lies is in the tools provided to players so they can communicate. Players are given a board containing dozens of universal symbols and several sets of differently coloured pawns and cubes to place on them. Players then draw a card containing nine different concepts to communicate which vary in difficulty.

Using a mixture of the pawns and cubes, players must then place them on the symbols on the board to communicate their concept. One symbol by itself will not communicate your concept and so the onus is on each player to get inventive with their combinations of pawns and cubes to create subcategories to the concept itself. An emblematic example is using the green question mark to indicate that the thing in question is a building whilst a red exclamation mark can be used to indicate its location in the world through the cubes being placed on colours to represent the flag.

Using the colours of pawns and cubes to create different sub-categories is where the magic of Concept comes to life and is where, admittedly, all of my play sessions abandoned the scoring and team setups.

Whilst some might see this very idea of throwing rule sets to the wind as a blasphemous act, what is crucial to understand about Concept is how much of a joy it is to simply play. There are guidelines for those that crave teams and are interested in the victory point structure, but the rulebook even accounts for how pleasing it is to play without structure.

Concept doesn’t rely on the physical actions of performance which can be off-putting in Charades or the vocabulary gymnastics of Articulate, but on the links players make between universal symbols. Delving deeper into this idea, we might derive the pleasure in play in Articulate from the endpoint of having successfully communicated the word, but Concept relishes in the journey made towards that endpoint.

Players frequently recount their steps and swap stories on how and why they built subcategories the way they did. It allows players to create meaning and forge a link between them and the person who figured it out.

The variations that players can take to explaining the same concept is a testament to how the game unlocks the vast expressive possibilities of the human mind. Because the symbols encapsulate such a wide range of ideas, it enables players to change tactic and create new subcategories that they think the other players might understand.

“In one session, I had to abandon my tactic of relying on the ‘Sistine Chapel’ being an iconic building in Italy and concentrate on the word itself. I managed to get my friend to say the word ‘Sister’ and then used the half symbol to get them to say ‘Sis’. Once their synapses started firing and connected this with the other categories they yelled out the Sistine Chapel and we couldn’t stop laughing”

Writing

This simplicity in mechanics and objective does almost all of the work for a rule book. But credit to the team at Repos they have written a rulebook which explains useful ways for players to combine their pawns and cubes to communicate anything they might desire. After a page of describing how a team game might work, the rulebook is well laid out to showcase a number of different examples.

This helps those who have been introduced into the game find their feet. The cards containing the concepts are well divided by difficulty. However, those striving for a tougher challenge may find some of the hardest difficulty ones relying a lot on colloquialisms.

These might not translate perfectly and only some players may be aware of them, which requires a tactic of spelling out each word which can be exhausting.

Components

Most of the component design is reliant on how clear each square is on board. Each concept is well coloured and paired with its opposite number making it easy to locate the squares you need. The player aid sheets which give a list of what each square can mean are durable and have lasted through many sessions of scrutiny. The concept components themselves are well made and satisfying to put down on the board, but if a room isn’t well lit then differentiating between blue and black can take a while and confuse players, meaning you’ll always hesitate towards the brighter colours.

If anything gets in the way of what you’re communicating then you’re less inclined to use it: either black or blue becomes redundant in favour of yellow and red. Though the components themselves are of a high quality and in no danger of breaking, the box is constructed well so that components are easily accessible and undamaged in storage. The bowl for the cubes is a particularly nice touch and adds to the whole presentation of the game to your family or board game group alike. Because of the sheer volume of cards though, you might want an elastic band to put around it so they don’t fly everywhere.

Art Direction

Everything in Concept is designed towards the theme of universality. From its difficulty modifiers to the exhaustive list of symbols on the board, Concept sits on a position of being accessible to as many people as possible. The white and grey colours used in framing the symbols and the rulebook serves this core theme at the heart of Concept. Any leaning towards something that isn’t universal taints the open possibility of communication by suggesting certain things. So the art is clean and serves this main theme propping up the game.

Replayability

Building off this theme of universality, Concept can sometimes dominate a whole evening of board gaming. The 110 cards which provide your subject matter offer so many examples that it would be rare to encounter the same one twice. And the breakdown in cards between different levels of difficulty ensures that younger players and those more unfamiliar with board games have a chance to play.

Because of this accessibility and focus on play before win/loss structures, Concept joins the ranks of games I use to introduce those unfamiliar to the hobby. It’s inherently social, its format is familiar, and it doesn’t rely on large systems which might be intimidating to newcomers.

Conclusion

Communication is a cornerstone of the human experience and Concept is one of the few examples which illustrates - through unstructured play - how enjoyable that basic function can be. Because Concept doesn’t rely on masses of components it has been competitively priced and accessible for a number of years.

Add to that the forthcoming release of the standalone game: Concept - Kids, the Concept series is a great opportunity to convert those board game skeptics in a familiar way.

What is your favourite 'gateway game' that you use to introduce people to the hobby?

"In one session, I had to abandon my tactic of relying on the ‘Sistine Chapel’ being an iconic building in Italy and concentrate on the word itself. I managed to get my friend to say the word ‘Sister’ and then used the half symbol to get them to say ‘Sis’. Once their synapses started firing and connected this with the other categories they yelled out the Sistine Chapel and we couldn’t stop laughing"

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

![TerrainFest 2024 Begins! Build Terrain With OnTableTop & Win A £300 Prize! [Extended!]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2024/10/TerrainFEST-2024-Social-Media-Post-Square-225-127.jpg)

That opening exchange may have sold me on this game alone

I had a bitter experience with reviews. Suppose you’re an entrepreneur and don’t want your business to suffer from customer reviews. In the article https://www.etxt.biz/subscribes/how-to-work-with-customer-feedback-10-practical-tips/, you can learn about 10 practical tips on how to work with feedback. I am sure this article will be helpful for any business area. The blog contains a lot of useful information.