Armistice Centennial: The Final Days Of The Great War Part Two – St. Mihiel & Meuse-Argonne

November 5, 2018 by oriskany

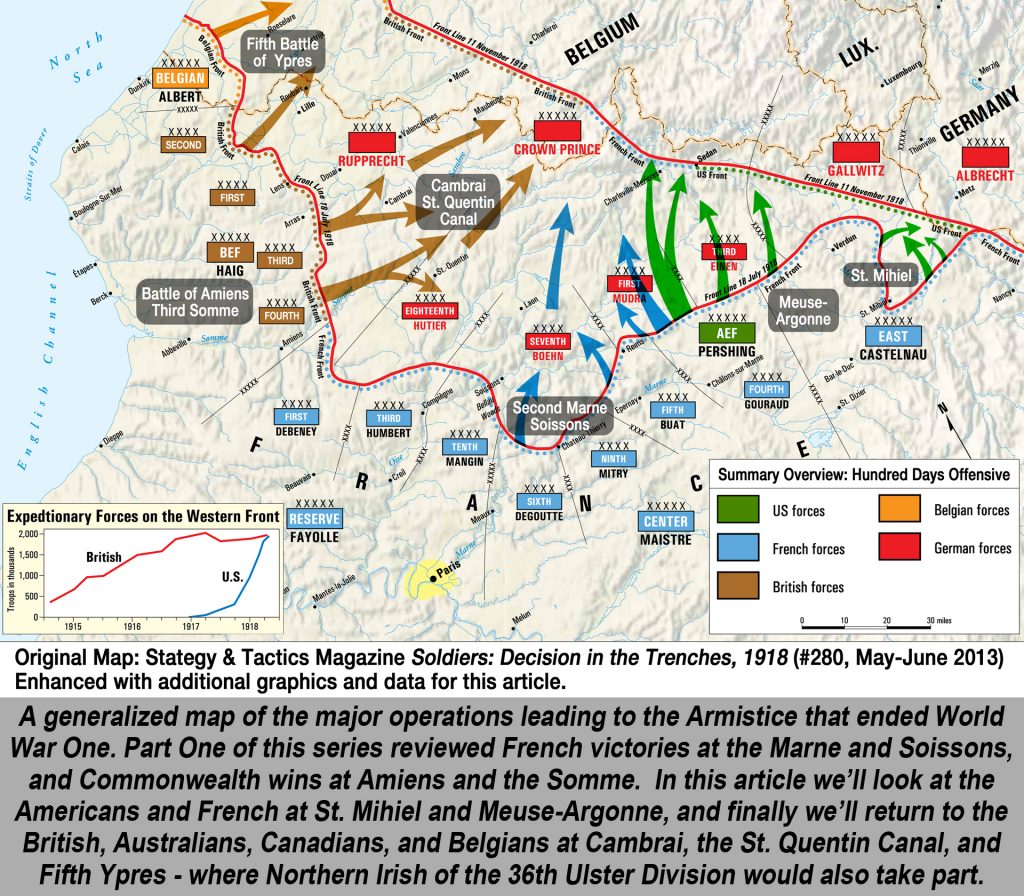

Welcome to Part Two of our article series commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Armistice that ended World War One. We’re also reviewing what would become known as the “Hundred Days Offensive” that finally led to this momentous, and solemn, milestone of history.

Armistice Centennial: The Final Days Of WWI Interview

If you’re just joining us, take a moment to check out Part One, where we summarized the background of the Western Front in 1918 and the opening of the Hundred Days Offensive. This included French and American victories at the Marne and Soissons, as well as British, Australian, and Canadian action at Amiens and the Somme.

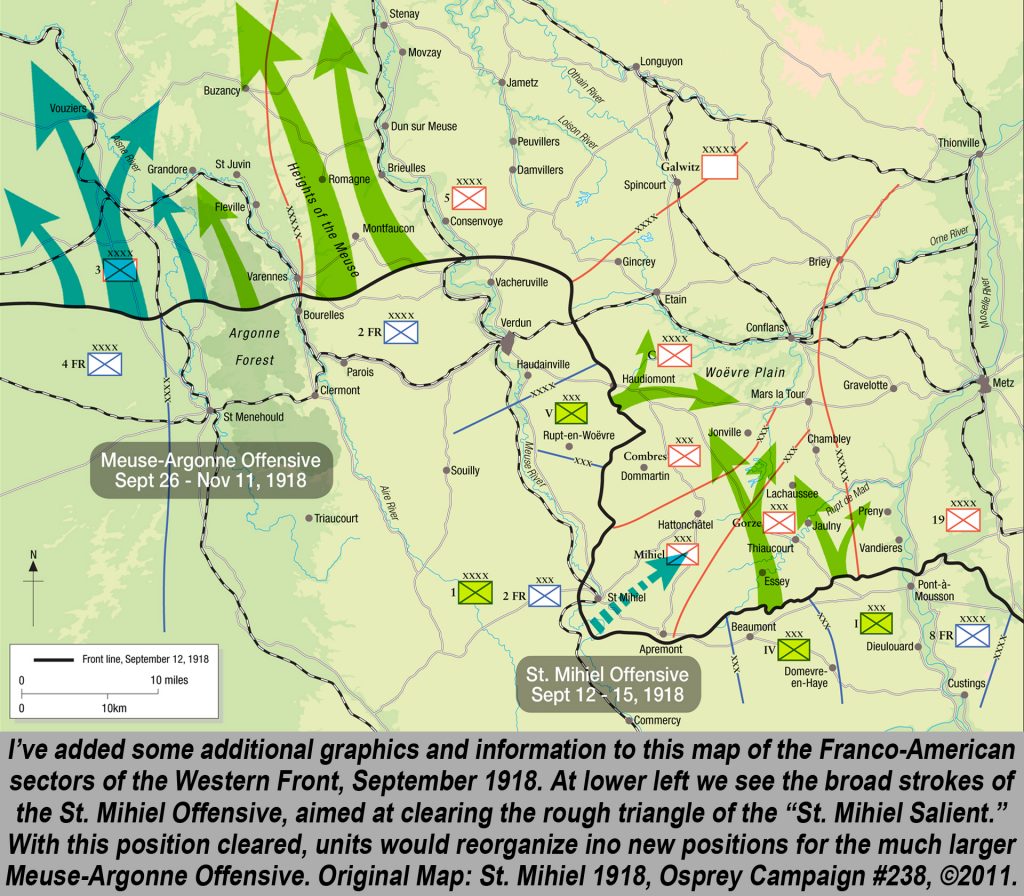

Now we shift to the southeast, back to the sections of the Western Front held by French armies, rapidly being reinforced by ever-increasing numbers of American troops. The next big phase of the Hundred Days opens here through September and October of 1918, with the Battles of St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

"Black Jack" Pershing & The AEF

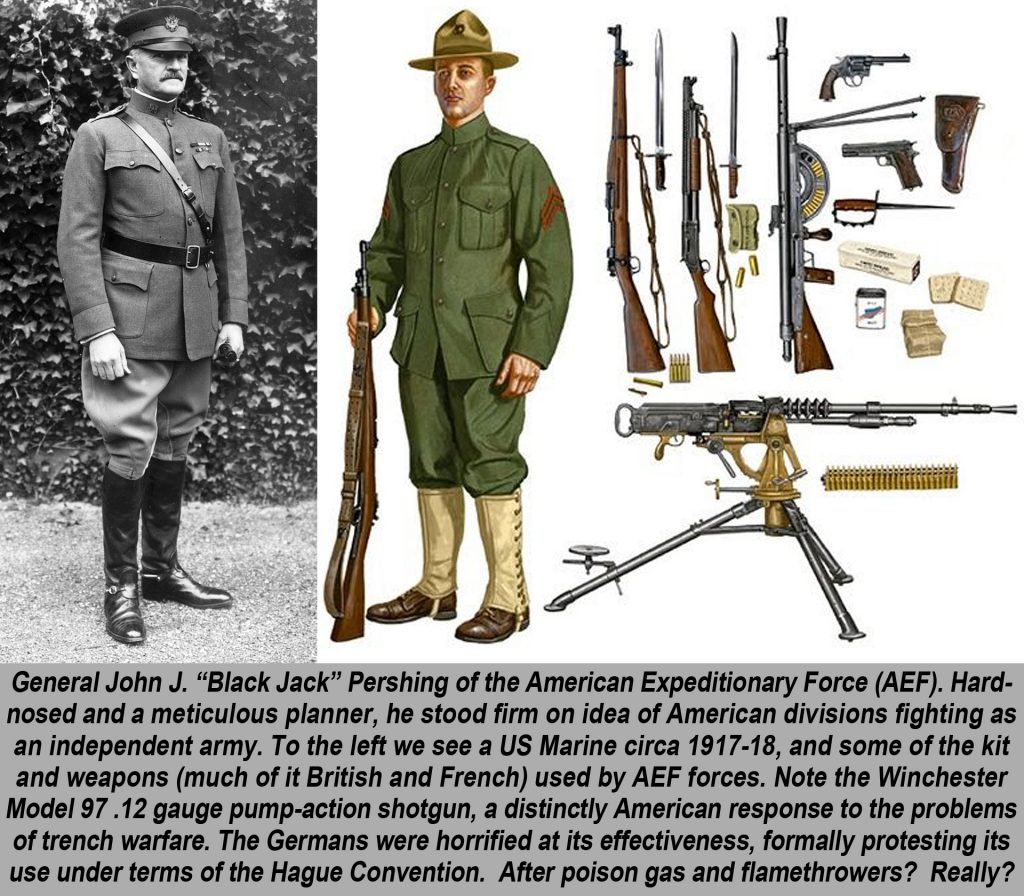

America had entered World War One early in 1917. But the US didn’t maintain a large standing army in those days, and so had to build one almost from scratch, then ship it over the ocean to the battlefields in France. Even for a nation with America’s population, economy, and industrial base, this was no small feat.

Even after this army was in place (nothing approaching appreciable numbers until early 1918), there was the problem of experience. Outside of small wars against the dying Spanish Empire and a few incidents in Asia and the Caribbean, the vast bulk of the American military had never heard a shot fired in anger.

The commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing. From the outset, Pershing faced strong pressure from British and especially French generals to immediately feed his new American divisions into Allied armies already standing in place, under British and French command, naturally.

Pershing, of course, would have none of it, and adamantly insisted that American divisions fight together, organized into American corps and armies, as an independent American command. Even as he eventually won this argument, Pershing had to admit that his men – strong, fresh, and eager as they were – lacked any battlefield experience.

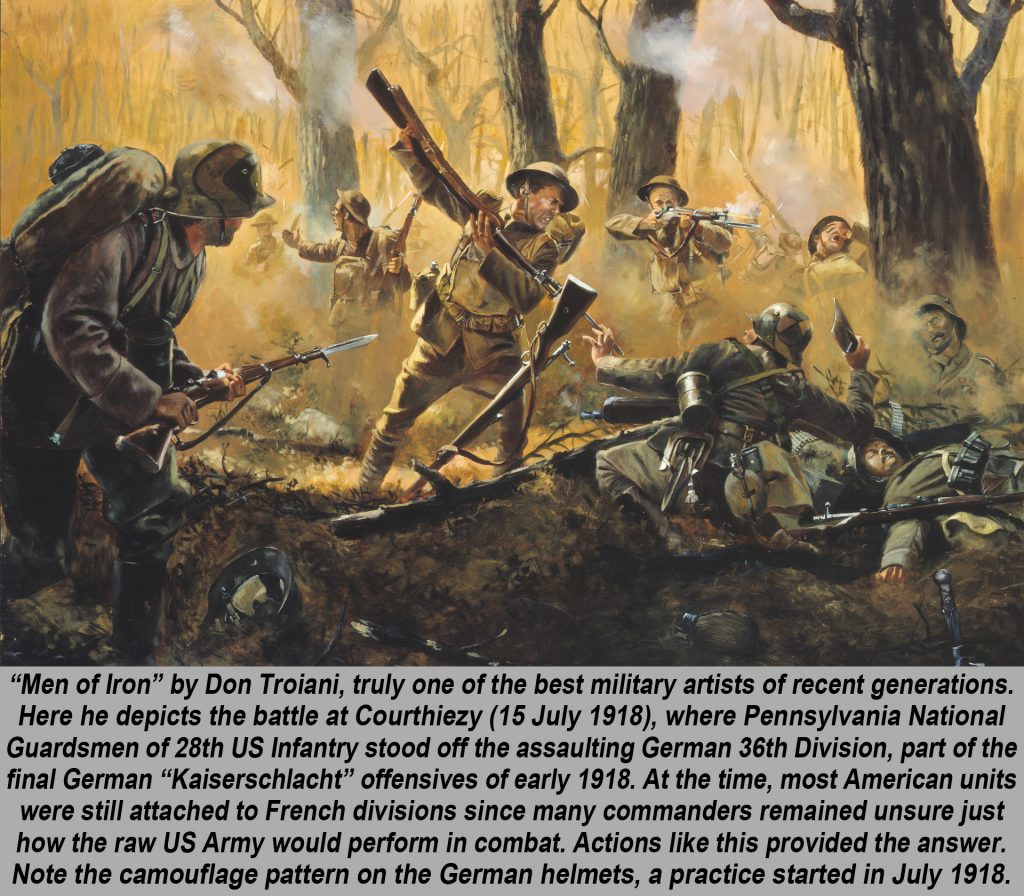

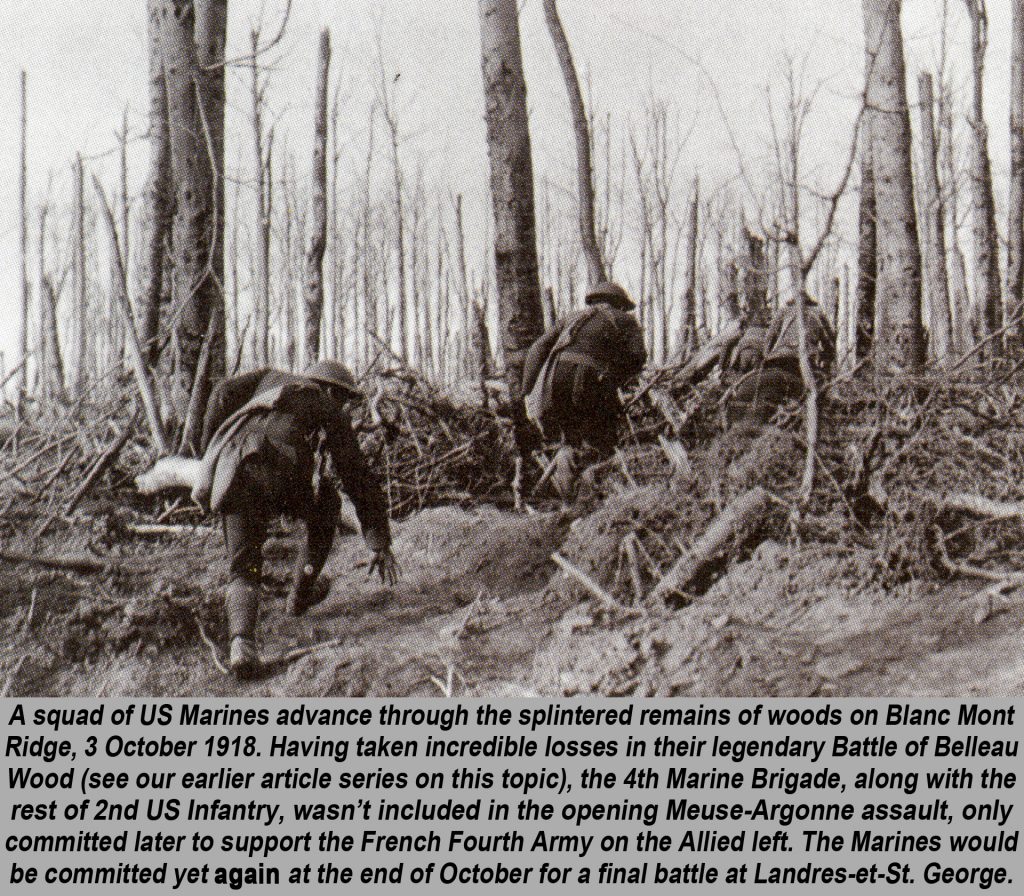

Accordingly, a compromise was reached, and earlier in 1918 select US divisions fought as part of British and French armies. Small numbers of Americans played a role in halting the St. Michael Offensive under British direction, and a larger role with the French in the Blücher-York Offensive. This led to the legendary Battle of Belleau Wood, covered in greater detail in our Great War series earlier this year.

But after American success alongside the French in the Second Battle of the Marne (July and early August 1918), the Americans felt ready to launch their own army-sized offensive as part of the overall Allied effort. The first phase of this operation would be an assault against the St. Mihiel Salient, in the Verdun-Metz region of northeastern France.

Battle Of St. Mihiel

The St. Mihiel Salient was a lopsided triangle of German-occupied France, about thirty miles across, running (very roughly) from Verdun to the northwest to St. Mihiel in the southwest to Metz in the northeast. The German Fifth Army had ten to twelve divisions plus support brigades and artillery entrenched here, a total of over 150,000 men.

The position was a vestige of German advances during the bloodbath battles of Verdun as far back as 1916. The French called the salient “l’Hernie” (the Hernia), and as the nickname suggests, were more than keen to be rid of this position once and for all.

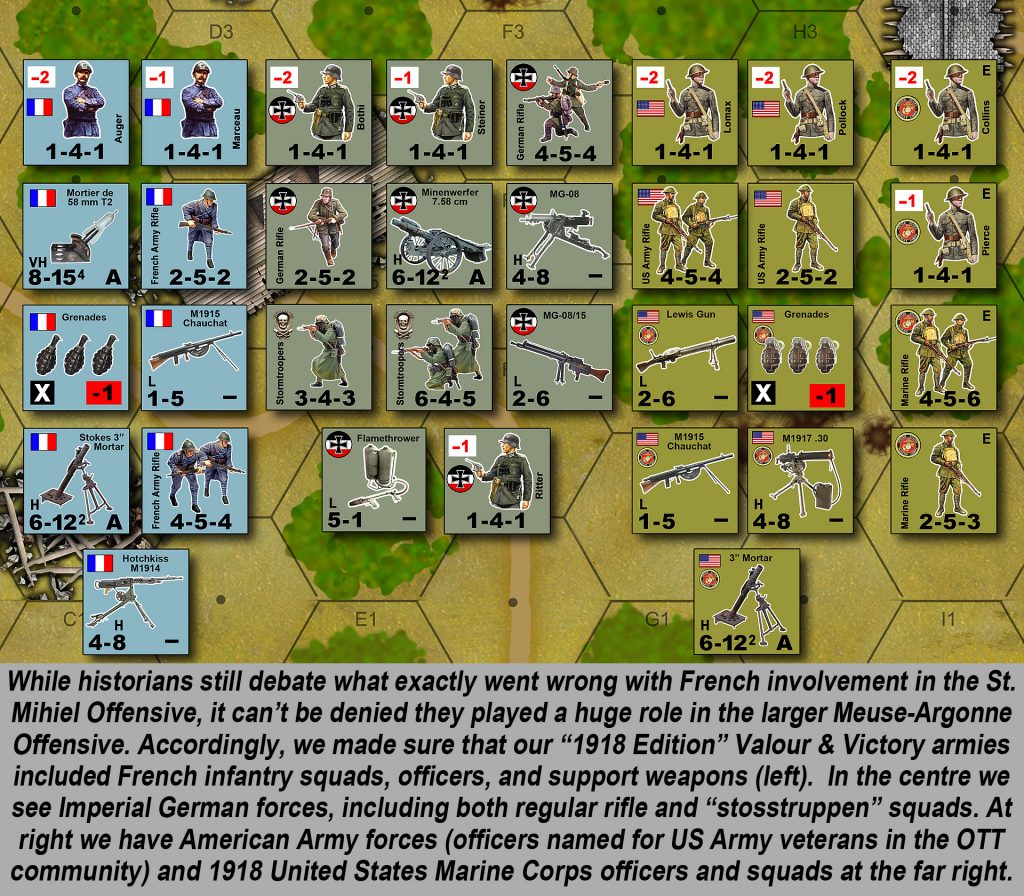

Although largely remembered as an “all-American” battle, it must be remembered that perhaps a third of the forces committed to the battle were in fact French. Although American divisions led the way, the French II Colonial Corps and three French divisions attached to US V Corps were tasked to provide support and reserve roles.

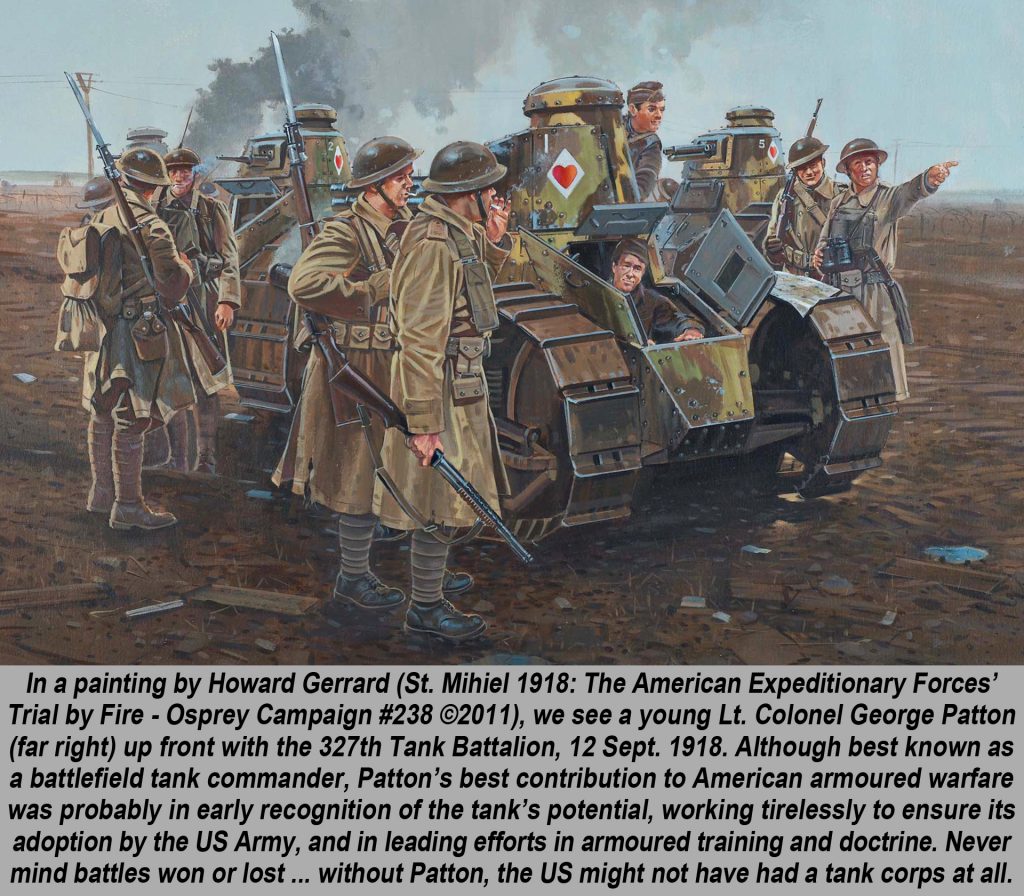

As a new army, the Americans were also sorely lacking in heavy equipment, like artillery and tanks. As a result, virtually all field guns and every one of the tanks used in the St. Mihiel Offensive were French. A young Lt. Colonel named George S. Patton fought his first big tank battle here, but we must remember he did it with French tanks.

The battle began in the wee hours of 12th September 1918. In a driving rain, American artillery opened fire against German positions all along the St. Mihiel Salient. After working over German road centres, reserve positions, and artillery batteries, fire shifted to the front line at 05:00 to support the actual infantry assault.

The main assault came from the southeast, formed around seven American divisions of I and IV Corps. These included the 1st US Infantry (The Big Red One), the 82nd Infantry (later to become the famous 82nd Airborne), and the 2nd US Infantry (including the 4th US Marine Corps Brigade of Belleau Wood fame).

The lead assault companies were accompanied by squads of combat engineers equipped with wire cutters and “bangalore torpedo” explosive tubes for blasting gaps through German barbed wire. Bridging engineers were also there to breach rivers the Germans had incorporated into their defence.

American tank units, equipped with French “FT” and “Schneider” types, supported the attack. In particular, 1st US Tank Brigade was commanded by a young Lt. Colonel George Patton. This brigade was split, with the 326th Tank Battalion supporting US 1st Infantry Division and the 327th supporting 42nd Infantry Division.

Part of the 42nd Infantry was the 84th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General Douglas MacArthur. As 327th Tank Battalion moved up to support, Lt. Colonel Patton found and conferred with MacArthur on a hill overlooking the battlefield. The meeting was routine combat procedure but assumes fateful foreshadowing given the role these men would play in World War II.

In the end, the offensive on St. Mihiel was only a partial success. Although the American assault succeeded in clearing the salient, the Germans had plenty of warning – a Swiss newspaper had reportedly even published part of the timetable. Accordingly, the Germans had already drawn up “Plan Loki,” a phased withdrawal from the exposed position.

Also, French cooperation was far from flawless. Although they provided the Americans with tanks plus 400 more tanks in their own brigades, II Colonial Corps did not pin down German units to prevent their withdrawal. Nor did they pursue once “Plan Loki” started. Thus, most of the Germans escaped the salient, frustrating American ambitions for a more decisive victory.

Still, Pershing’s detailed operational planning and “up front” tactical leadership by men like Lt. Colonel Patton made this an important win for the fledgeling AEF. Massive air cover also played a key role, with 1,431 aircraft supporting the attack (led in part by American air legend Colonel Billy Mitchell) - although only 40% of these were American, the other 60% were British, French, and even Italian.

Meuse-Argonne Offensive

General Pershing soon called a halt to the St. Mihiel Offensive, withdrawing units to assign them to a new, much larger operation, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. This attack would include more French support, starting in late September and extending all the way to the very end of the war on November 11th.

The Meuse-Argonne would be the largest (and bloodiest) military operation yet mounted in American military history. Historian Carlo D'Este writes that the three-hour artillery barrage would expend more ordinance than both sides fired through the entire four years of the American Civil War.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive would take its name from the two major terrain features on the battlefield, the Meuse River to the east (running generally south to north, toward the Belgian border) and the Argonne Forest, dominating the western landscape. In all the assault corridor would be about thirty miles wide and thirty miles deep.

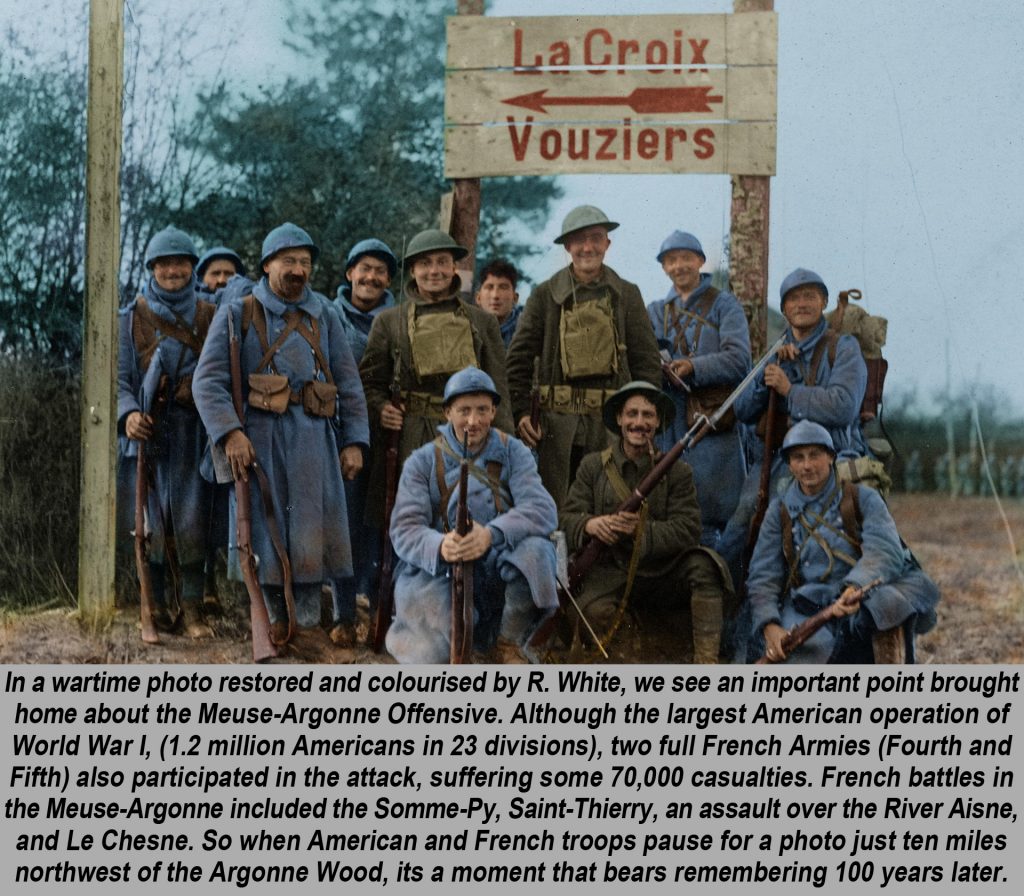

Whereas the St. Mihiel Offensive had been a primarily American operation with French support, the larger Meuse-Argonne Offensive would feature much larger French formations in an equal role. In addition to the AEF’s First Army, the French Fourth and Fifth Armies would also participate, primarily off the American left wing.

The offensive started on 26th September and although the Americans made good progress on the first day, disorganization and American inexperience (leading to very steep losses in some areas) stalled progress on the second day. German reserves were then mobilized for powerful local counterattacks, leading to further complications.

The French, meanwhile, actually exceeded initial American advances, partly because the terrain was more open in their sectors of attack. Renewed American advances starting on October 4th then outpaced the French, creating dangerous gaps in the Allied front, exacerbated by choppy coordination between American and French divisions.

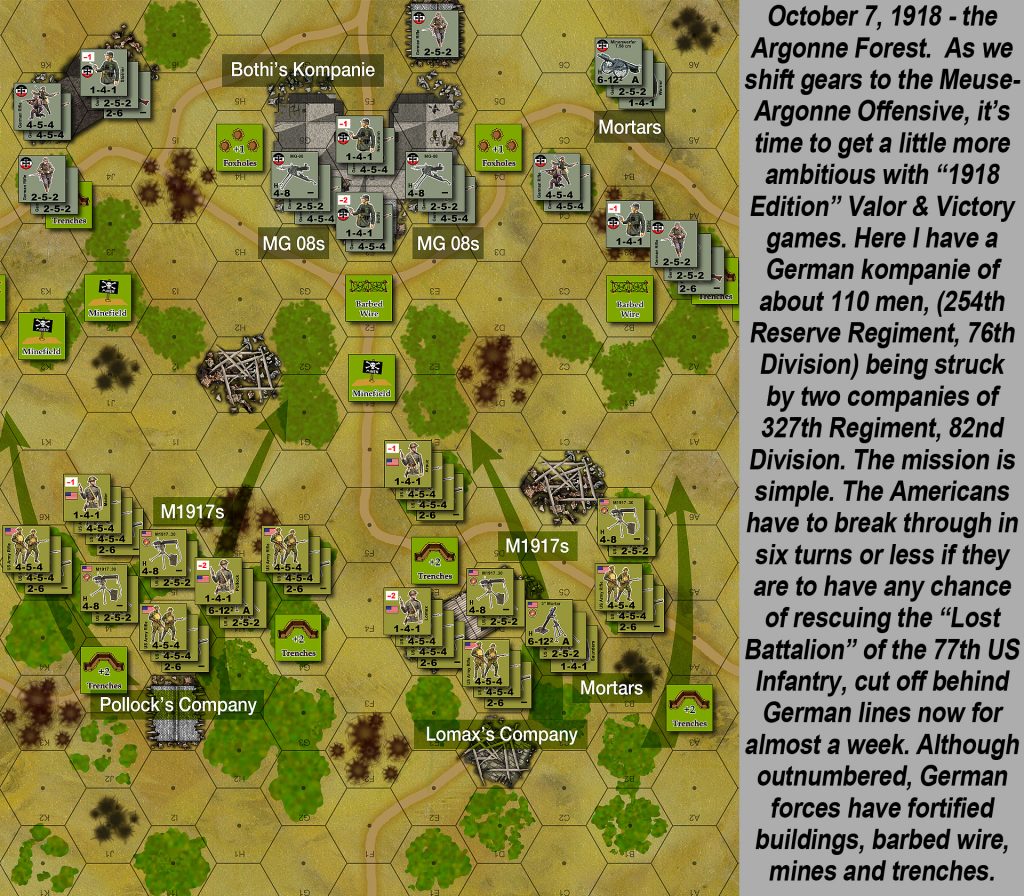

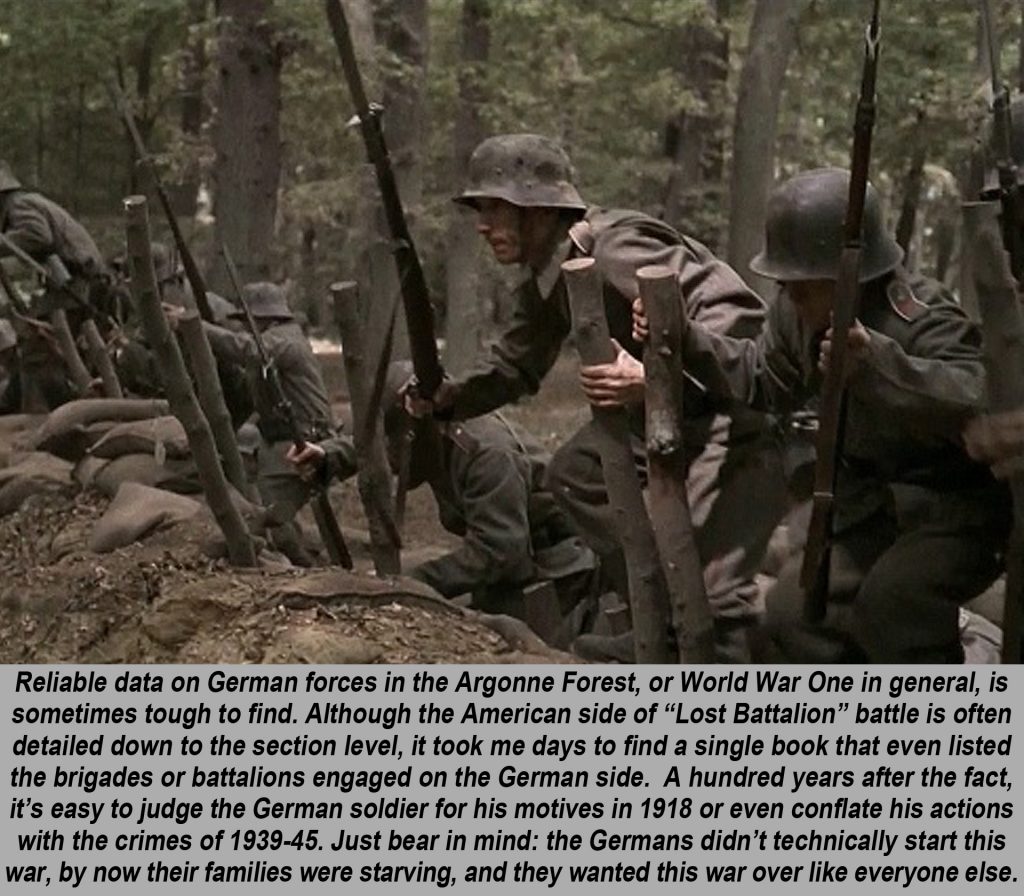

One such gap resulted in the infamous “Lost Battalion” incident with the 77th US Infantry on the far left of the American line. Garbled communications about just how far neighbouring French divisions had advanced resulted in part of the 77th being cut off by counterattacking units of 2nd Würtemburg Landwehr Division and 76th Reserve Infantry Division (LVIII Corps), recently transferred to the German Fifth Army.

Cut off for several days, shelled by their own artillery, and hammered by German attacks, survivors of the Lost Battalion were finally relieved by elements of the 1st US Infantry (Big Red One) and 82nd Infantry (future 82nd Airborne). Seven Congressional Medals of Honor were awarded for the action.

In the end, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was a success, despite 120,000 American and 70,000 French casualties. German losses were even worse, and the Allied advance was still underway (just ten miles shy of the Belgian border) when the Armistice of 11th November ended the fighting.

Perhaps the most poignant perspective on American forces fighting in France can be taken from a simple inscription painted on the walls of the Verdun fortress, recorded years later in the Yank army weekly newspaper:

Austin White – Chicago, Illinois – 1918

Austin White – Chicago, Illinois – 1945

This is the last time I want

to write my name here.

Now it’s over to you, the OnTableTop community. What do you think of these closing battles of the Great War? Have you tried any of them on the gaming table? What do you think of the difficulties of coordinating allied units from other nations? Post below, and thanks as always for reading.

Come and take part in the discussion below and follow along with the article series as it develops...

"The first phase of this operation would be an assault against the St. Mihiel Salient, in the Verdun-Metz region of northeastern France..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"One such gap resulted in the infamous “Lost Battalion” incident with the 77th US Infantry on the far left of the American line..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Heading off to work so I’ll have to read this whole article later – but I always like the maps in these articles. You say “original map” and credit a source, but these don’t come like this, do they?

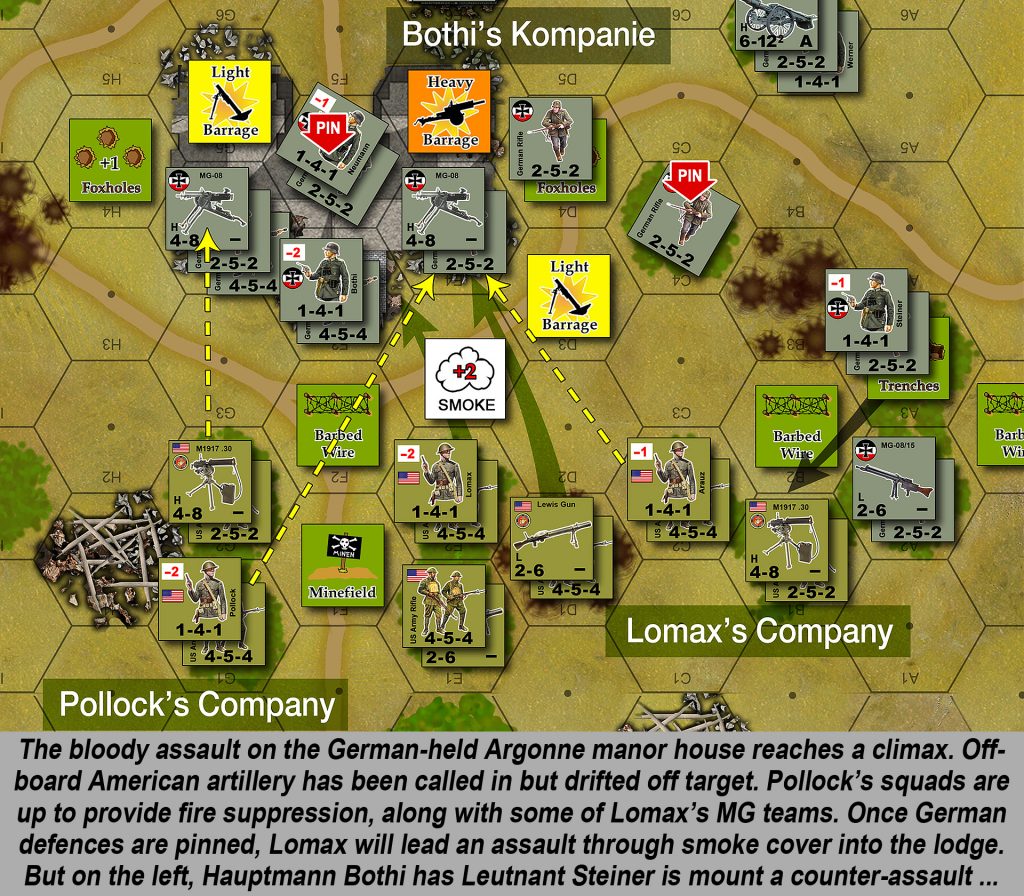

Thanks very much for kicking us off, @gladesrunner. No, you’re right, I do enhance those maps with corrected / updated / additional information, if nor no other reason than to bring their data into alignment with what’s specifically addressed in the article.

They say a picture’s worth 1000 words, and with a map I can layo ut a battle with more clarity than three paragraphs of text I can use for more interesting information. 😀

@oriskany, another good one James, it makes a pleasant change for someone to cover the last battles, I remember the old BBC series ‘The great War’ made a big thing of the final German Offensives, but glossed over the later Allied pushs.

Interesting, @bobcockayne – Here in the US we have almost the opposite problem, these final offensives dominate the discussion because this is where the US made its biggest battlefield contribution. St. Mihiel sees figures like Mitchell, Patton, MacArthur, and others as scrappy young officers getting their boots dirty, so its ready-made “prequel” material.

And of course Meuse-Argonne was the biggest and bloodiest battle the US Army had yet fought at that time.

But the previous 3.5 years of World War I is often handled almost like the opening crawl of a Star Wars movie.

“For years the powers of Europe have been locked in a bloody trench stalemate (not really true), now the Americans have arrived with the full weight of US industry behind them (not really true) to turn the tide (not really true) … 😀

@oriskany think its a British documentary thing, British victories (except the recent Trafalgar anniversary when the Beeb had great fun rubbing the victory in to the French) tend to be ignored or forgotten.In the initial World at War release , remember there was a whole episodes to the British defeat in Malaya long retreat in Burma, and how miserable the conditions where, but nothing at all about Bill Slims battles at Kohima and Imphal never mind the admin box or his successful offensive to retake Burma.

Yeah, @bobcockayne , again, we almost have the opposite problem in the US. 😐 If American forces were’t involved, weren’t playing a leading role, and didn’t win … it didn’t happen. It’s actually kind of a shame.

I would submit that the China Burma India theater in WW2 is grossly overlooked in general, no matter who led the campaigns or won the battles.

@oriskany

For years the powers of Europe have been locked in a bloody trench stalemate (not really true), now the Americans have arrived with the full weight of US industry behind them (not really true) to turn the tide (not really true) …

Don’t give Hollyweird Ideas!

Too late.

😀

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PyJwtC8kwJM

I would disagree with this a little. They only had 26 episodes to cover the whole of the war. It only had 1 episode to cover the entire Middle East campaign. One and a bit to cover Operation Michael and one and a bit to cover the 100 days and they had to fit in the Balkans,The Eastern Front and the Italian campaign plus the air and naval war . Personally I think they did a great job and is still my favourite documentary series and is still available on you tube for those interested

Episode One

https://youtu.be/Es4zhqqM5lU

I’m unfamiliar with the series, so I’ll take your word for it. 😀

Any documentary has to make major cuts, simplifications, and generalizations. I always knew this, but the point was really brought home once I started recorded interviews with Beasts of War / OTT.

They’re almost painful sometimes, with the amount of material and detail that has to be left out. 🙂

Finally had a chance to sit down and read the article. Well… Actually cheating and doing it while the kids are taking a test at school. Either way, another great entry!

It’s interesting how wildly control was swinging back-and-forth in these areas so near the end of the war. I mean it seems like control was changing and battles were happening but yet nothing was ever really different at the end. I might be completely missed reading everything. I just really get a sense futility .

Thanks again, @gladesrunner – the wild swings back and forth really come into focus if you pull back and look at the whole war, or even just all of 1918. Then you have the 1st, 2nd 3rd, 4th and 5th Battle of Ypres – when the Somme fighting we talked about last part had 1st Somme, 1st Somme 1918, 2nd Somme 1918 – sometimes called 3rd Somme for clarity …

When the battles start to sound like bad movie franchises – you have a problem. 😐

But once the early 1918 Kaiserschlacht offensives had been contained and halted, these “Hundred Days counterattacks actually caved in the German front and brought about the end of the war so fast it actually surprised the winners, not to mention the losers.

Meanwhile, the Australian Infantry + British tanks vs German Infantry + German entrenchments battle is hopefully kicking off this afternoon (a little late, admittedly).

https://www.beastsofwar.com/project/1288632/

Interesting to see how the C&C played out at that stage, echoing a lot of the thinking from both sides in later wars about who should fall under whose command. I also found the comments interesting about the lack of security about battle planning and the knowledge the other side had of upcoming attacks.

Back in September, I posted a link to a battle north of this area in the British sector, but happening at the same time as Meuse-Argonne. Some very quick moving developments in these last weeks –

https://www.beastsofwar.com/forums/topic/100th-anniversary-battle-of-canal-du-nord/

Great link and forum topic, @donimator – we doc over Currie’s Canadian Corps at this Battle a little in Part 03 – although not in nearly as much detail as you mention in your form post (along with St, Quentin Canal, Hindenburg Line, etc).

Currie just before 1914 was given CAD$ 10,000 to buy new uniforms for the 50th regiment. Instead of buying the uniforms he used it to pay off his personal debts

he 50th Regiment’s honorary colonel, William Coy, had promised to underwrite the regiment with $35,000 and Currie planned to use these funds to pay the uniform contractor.

Unfortunately for Currie, Coy did not follow through with his financial commitment to the regiment, leaving Currie’s accounting sleight-of-hand potentially exposed

Almost three years passed until two of Currie’s subordinates, Major-General Sir David Watson and Brigadier-General Victor Odlum, stepped in and repaid the money Currie had stolen from the 50th Regiment

Now there’s an angle I was unfamiliar with. 😐

The Last Hundred Days

The Last Hundred Days is the epic, inspiring story of the Allies’ finest hour – and the invention of modern warfare.

In early 1918, the Allies had their backs to the wall as a great German offensive swept westward in a final bid to win the bloodiest war of all. Yet, little more than six months later, Germany was forced to accept crushing defeat.

From command headquarters to the frontlines, visionary leadership, revolutionary tactics and the courageous determination of the Allied forces on the Western Front turned the tide and won the Great War.

From the visceral experience of the soldiers on the battlefield and the nurses who patch up the wounded with unimaginable bravery, to the crucial decision making of the generals, this drama documentary will bring the men and women behind WWI’s finest multinational feat of arms vividly to life.

The Last Hundred Days (2×60′) is an international co-production involving BBC Scotland, Foxtel Australia and The History Channel in Canada. It’s produced by Electric Pictures out of Fremantle, Western Australia. The Commissioning Editor for the BBC is Ewan Angus. The Executive Producer is David Harron.

Check out the above recently broadcast on BBC it covers the innovations of the new commanders in the Canadian, Australian in the last 100 days. The tragic losses of the U.S troops due to lack of experience and over enthusiasm.

Is this a promo from a TV documentary? 😀 Sounds like we’re covering many of the same topics. We have one more article to go, in addition t o this one and the one last week, plus the 50- minute interview with John and Gerry, plus hopefully and XLBS segment coming up for the actual Armistice Centennial (Sunday, November 11).

Yes, this was the spiel describing the Drama/Documentary on the BBC. There were some very interesting points like the technology developed by the allies using sound waves to locate enemy artillery so their counter battery fire became deadly to the Germans. Also the development by the Germans of Anti-tank rifles to counter armour.

The overall efforts by the allies set the template for modern warfare combining air and ground forces including tanks supported by artillery to overwhelm the enemy. Sadly lessons we forgot and the Germans used successfully in WW2.

See, @ozzie , this is why I love the comments section. Serious, not being sarcastic. Everything Id din’t have room for in the article series has a chance to come out.

I had an image saved of the German antitank rifle ready to put in the series, but ran out of room.

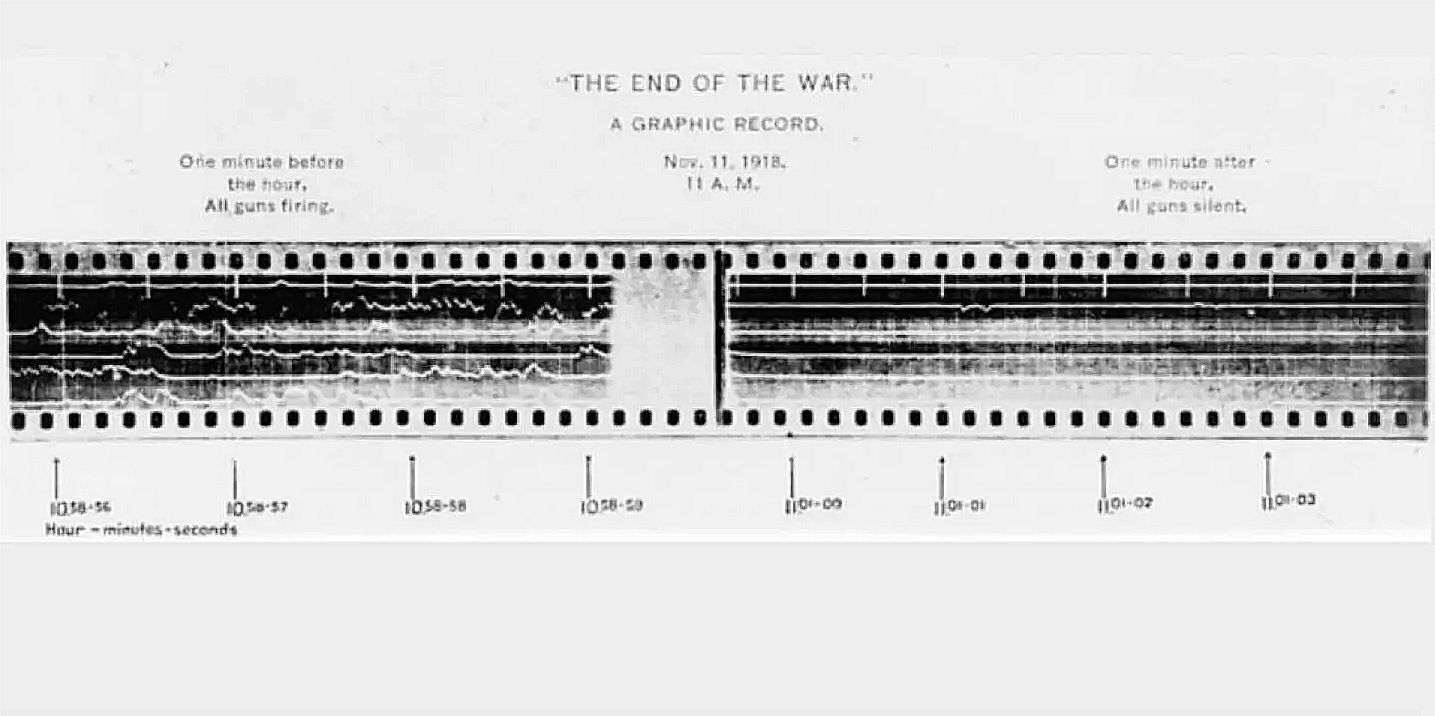

Also, I have an image somewhere of one of the sound recordings you’re talking about. I wasn’t talking about artillery direction finding (again, didn’t have the room), but there’s a haunting image of the paper recording of one of these sound detection devices … and you can “see” where all the artillery stopped at 11:00 AM 11 November 1918. I’ll see if I can find it and post it as well.

Okay, found it.

That’s a great picture of the AT rifle, the sound recording was part of a News piece on the BBC only a couple of days ago. I have a great interest in this conflict as my Grandfather was in the Warwickshire Regiment throughout the war and luckily survived the ordeal especially the Somme battlefield. Another great series Jim.

Thanks for your interest and your comments, @ozzie . Man, the Somme was no joke, that’s for sure. I think the first day of the Somme is still the bloodiestsingle day in British military history.

Be sure to check out Part 03 next week, where we see the Somme countryside is cleared once and for all, leading to push-backs into Belgium further north at Ypres, Messines Ridge, Passchendaele, and Courtrai.

A good read @oriskany interesting to see the number of famous figures are in the grinder probably with other’s at the front mud tramping, on a side note the picture of the troops going to the front does anyone know if they all survived the battle/war.

Thanks, @zorg – the future general I mentioned (Patton, MacArthur, Mitchell) were up front with the men, leading St. Mihiel offensives right at the spearhead. Of course they were more junior in rank at this time.

As you said most of the program’s made covered the really big battles forgetting all the other smaller one’s so thanks for covering the forgotten battle’s to enlighten people to the bigger picture, (including my selves) @oriskany

No worries at all, sir. My pleasure at always.

Also, I hope to be recorded either VLOG, Podcast, or XLBS segment – to air on Sunday 11 November. So if you watch it on your Sunday morning, European time, you’ll be on the 100th anniversary of the Armistice almost to the HOUR.

I will try my best.

Epic. 😀

Another great and educational article. As you said in the first article, with the 100 year anniversary, it’s important to not just play the games but to also remember.

The closest I have ever come to combat is trying to board a London Underground train at Oxford Circus in rush hour. And while I am a veteran in that respect, I always feel somewhat uncomfortable with gaming some of these historical events. However, for me, a large part of the gaming is to also understand the history, geopolitics, events and individual stories. In this way, I try to remember, learn and, despite my tiny role in the world, to hopefully not repeat past mistakes. These articles only continue to add to that learning.

Thanks very much, @redvers .

While I obviously don’t share your opinion re: discomfort wargaming historical events, I do of course agree that now is a great time to pause and remember something of what happened 100 years ago this month, and how it continues to impact our world on a global scale to this very day.

A very good one again and a good refresher for some things I already heard and read about.

That camo pattern on the German helmet model 1916 was called mimickry, right? I was always astounded how colourful it was, but I think it served the purpose well to break up contours. And, not to forget, it looks good on painted miniatures.

That general, Mitchell, was he the one who gave the name for the American bomber model of WW II? Patton was a tank officer, MacArthur infantry, but Mitchell, was he in the air force? – In a documentary on TV about tank warfare Patton was mentioned and they told us about his whipping his men into practice endlessly and relentlessly until he was satisfied. I wonder whether he was so notoriously foul-mouthed then as he was later :-). In that docu they also said Patton was wounded and, after that, spent the rest of his WW I time in a military hospital, extremely unhappy not to be able to take part in the fighting.

I always wondered where the name “bangalore” mine comes from. Is that the city in India or is it onomatopoetic? “BANG”alore.

You mentioned air support in the Allied attacks against the Germans. I suppose that doesn´t mean dog-fighting, of course. However, how do we have to imagine how air support was carried out? Were there ground attacks with MGs alongside infantry attacks, was there bombing of certain positions and did they use bombers like we imagine bombers look like (heavy, more than 2 crew, a considerable bomb load) or were they fighter-bombers, combining the two methods and looking accordingly? How did they solve the problem of coordinating artillery barrages and air support? A matter of either or? How did they tackle the problem of air support in wooded areas?

I know anti-aircraft-weapons were not far developed at that time. Did the Germans have any (good ones)? – I remember a picture of a British soldier, from 1915 I think, who had a MG fixed to a bicycle wheel and then the bicycle was put on his hind wheel so that the MG pointed to the sky. I assume restricted effectiveness. How were things in 1918?

That picture with the Germans leaving their trench is from the movie about the cut-off American unit, right? I watched this movie a few times and what I took from it was the extraordinary fighting spirit of the men. One of them said: “Hey, they don´t who they´re fighting against. We´re from Brooklyn.” Great scene.

So far we have covered the North, the North-East and several other places where the fighting went on. Were there any fights in the Vosges area? It is quite difficult Terrain, but for the French it would have been the shortest way into the herat of Germany. They didn´t try their luck here, right?

Are we going to learn something about the end of WW I in South-East Africa? They stopped fighting after Nov 11th, correct?

Looking forward to te third bit of this series? @oriskany for the win.

Thanks very much once again, @jemmy ! 😀

From what I understand, (Osprey, +four or five accredited military artists) – that German camouflage pattern on the helmet only starts in July 1918. I don’t know what the name of it was.

Yes, Billy Mitchell had a bomber named after him later. He was a very influential person in getting American airpower off the ground (no pun intended), especially in terms of bombing and tactical air support. Technically he was in the Army, the US Air Force wasn’t founded as a separate branch until 1947. Before that it was the US Army Air Corps, and later the US Army Air Force.

I feel Patton’s biggest contribution to American tank warfare wasn’t on the battlefield, but in the procurement office, the classroom, and the training ground. Like Guderian or even Tukhachevsky, he took the ideas, added his own elements, and then STUCK WITH IT, got the funding, and actually got “tracks in the mud” – unlike some other people that are credited with “inventing” interwar tank doctrine.

I honestly don’t know for sure, but I always thought Bangalore torpedoes were first used at a battle / siege at Bangalore during fighting there in the 1800s.

I always wondered where the name “bangalore” mine comes from. Is that the city in India or is it onomatopoetic? “BANG”alore.

Tactical bombing in WW1 is, well, hit or miss (again, no pun intended). They literally threw bombs over the side, I think later they managed to create an early version of hardpoints where bombs would detach with the pull of a lever. There was definitely no radio for close air support. So nothing “tactical.” These must have been pre-planned strikes on known targets or targets of opportunity undertaken at the discretion of the pilot / squadron leaders.

AA weapons in World War I were just getting started. The British had some dedicated batteries they were trying out, mostly 3-inch weapons to be used against balloons zeppelins and high flying bombers. Definitely more of a deterrent to spoil bombing aim or up close photo recon rather than an actual threat. Not sure about the Germans, though.

Yep, that shot is from the Lost Battalion, discussed in the article.

The primary reason I don’t think the French attacked in the Vosges is they weren’t trying to get into Germany so much as they were trying t get the Germans out of France. Also, the Germans have some very serious fortifications in and around these areas. Defendinging and counterattacking in areas like Verdun, Chemin des Dames, and especially the Marne will take higher priority as they threaten Paris.

“ @oriskany for the win . . .” Thanks very much. 😀

@jemmy @oriskany

On helmets

In July of 1918 a directive came down from Chief of General Staff Ludendorff which called for helmets to be painted with a camouflage pattern. The directive reads as follows:

Chief of the General Staff of the Field Army

II. No. 91 366

7 July 1918

Through a purposeful, variegated surface paint on cannons, mortars, machine guns, steel helmets, etc., these devices may be much more easily hidden from view than before.

The authorized trials have produced the following results:

1. Steel helmets:

A painted surface with one color (e.g. green or light brown) or with small splotches of a variety of colors is superior to a standard single color helmet, although it still allows the recognition of the characteristic form and silhouette.

In this regard, a three-colored surface which has had the borders blended, simulating a shadow effect is not recognizable beyond a distance of 60 meters.

Particulars regarding a useful surface: Dull colors – the helmet must not shine. Sprinkling the still-damp oil paint with fine sand stops the surface from glistening in the sun.

The choice of colors is to be purposely changed according to the time of year. One of the three colors must match the basic color found in the region of fighting.

Suitable at this time: green, yellow ochre, rust brown

Separation of the surface of the helmet into equal-sized portions, consisting of large, sharp-cornered patches.

Support – On the front side of the helmet, no more than four colored fields must be visible. Light and dark colors are to be placed next to each other. The colored segments are to be sharply separated from each other by a finger-wide black stripe.

Necessary coloring materials for 1000 helmets: 5 kilograms each of ochre, green and brown; 2 kilograms of black.

After ongoing scientific testing, I have requested the War Ministry to regulate the appropriate seasonal color scheme. Until that point, I request that painting be carried out in the above-mentioned manner.

(signed) Ludendorff

To:

all Army Groups (5 each)

all Army High Commands (20 each)

Inspector General of Artillery Schools

General of Pioneers attached to General Headquarters

Commanding General of the Air Forces

Army Mortar School

Commander of the Gas Troops

M.SS Command Rozoy

General Staff Course Sedan

Field Artillery and Foot Artillery Practice Grounds

Chief of Field Transportation

Offices la, Ic, B, Munitions. Z, P, F, Illb (3 each)

Awesome! 😀 Well, there you have it. In addition to “Osprey, +four or five accredited military artists” … I can now add @torros as a source to that July 1918 date. 😀 Thanks for the back-up! 😀

There were initial trials in 1916 with a Bavarian regiment but this was in just covering the helmet in cloth

Yeah, the question from last article series was when the Germans started *painting* the helmets like that *wide-scale,* so people knew whether to paint their FoW Great War German minis like that.

Ive read a but more about it. Nothing directly was said but painting the helmets was not very widespread. It seems like it was the better units like the Strossstruppen painted them. I did read on a collectors forum that lot of enterprising French natives and Allied troops after the war painted a lot of the helmets you see today as they got a better price for them than the normal plain steel helmets when selling them to tourists

Ha! That’s great. Painting up German helmets yourself to a “faux stormtrooper” scheme to jack up the souvenir price. Three cheers for capitalism. 😀

Great overview @oriskany.

I think it is the nature of the beast when it comes to documentaries that other nations are not mentioned. They are out together for their target audience and the audience in turn is looking to see if they catch a glimpse of grandfather so and so. Covering another nation gets in the way off this. Most audiences want to see how they won the war. I think it is just as hard for the producers getting funding as well. The financial backers are not going to be as generous in their nation is going to be placed in the second row. So I believe it is a hard balancing act for the producers of documentaries to create what they want and what is actually being paid for. Some good examples of this being taken to the extreme were a number of documentaries made in the US back in the 90’s. They were funded by the U.S. army Psych Ops with some very strict conditions. The US must be seen in the best possible light, apparently the Battle of the Bulge was a ride in the park. But then at points regardless of subject matter some random piece of modern US hardware would be thrusted upon the viewer telling you that this was the best of the best of the best. These documentaries could also be identified by the mention of Fort Bragg in small print in the end captions. I am by no means singling out the US by any means here other than a case in point of how difficult it must be for someone to come up with an idea and produce their documentary without the people with the money demand changes to maximise their return.

The treatment by German forces of the Belgians along with the Poles and Jews on the eastern front were a foreshadow of what was to come in the next war.

It seems to come from the end of the Franco-German war were the Germans came up with a policy for ruling the civilians in captured territories. The basic idea is make them too afraid to argue. I don’t remember the actual German name for this policy but it could be crudely translated into English as German Beastlyness. The English make much of this translation in their propaganda of WW1 and resurrected again in WW2.

The issue is that it was meant only to frighten the population not harm or kill. However in practice too many things can go wrong and too far, too easily. Today it is doctrine in a number of armies that prohibit the use of soldiers to police a population that have seen recent combat. However at the time in WW1 the Germans did not see the danger in this.

I have seen a number of documentaries now on the list battalion and it is still an amazing story. I have seen a couple on the Meuse-Argonne now but I have had to join them up as if the documentary is made in Europe it is looked at from one light and if American it is in another. I think the battle shows the Pershing was a good field general. He saw when the advance was failing and was able to get it going again. The episode off the old Battleplan series, Attacking the fortified line takes a good look at this battle and how Pershing handle it.

Thanks very much @jamesevans140 .

I agree with your points on the documentaries. I’ll be honest and go a step further – I experience a little of it myself.

Here on Beasts of War when I appear in an interview or write an article series I remember that a big piece of my audience is in the UK so I make sure the UK is given a healthy slice of the limelight. When an opportunity presents itself to spotlight Irish units, especially Northern Irish units, I damned sure make the most of those as well. Is it pandering? I hope it never comes across that way. I just try to present material that I feel will be interesting to the audience at hand.

That said, when @neves1789 and I sat down earlier this year to put together the Spring Offensive series, and he said he wanted to write much of the articles himself, I agreed … on the condition I would write the Belleau Wood article on my own. Not just as an American, or a veteran, but specifically a US Marine veteran, to showcase the 100th Anniversary of the Battle of Belleau Wood to tens of thousands of subscribers was literally a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But even there we tried to keep it objective, highlighting not on Marine courage and tenacity but also a certain degree of inexperience and lack of tactical finesse.

I’m always surprised by how strongly the Australians in the community speak up for their veterans, commanders, and parts in these various campaigns. People asked why they weren’t featured more heavily in the Kaiserschlacht Spring Offensive series, I would (a) argue that Australian units didn’t take a prominent role in the specific battles under discussion, but at the same time (b) they DEFINITELY do it in the battles in THIS series. By the way, I hope you saw Part One of this series that features Monash and his Australian Corps so highly not only at Hamel but also the opening of Amiens. They’ll also be featured in Part Three where we talk about the drive through Cambrai, St. Quentin (Canadians are huge there as well), and the drive to the Hindenburg Line.

Totally agree with you @oriskany.

Yes I did indeed I read part one and left you a rather lengthy reply on Monash and his play book as you call it and an Australian perspective on the 100 days as it is bitter sweet for us and I explain why. To keep things easy for you, you can reply here instead of jumping back and forth.

Yes we do like to put our guys forward in this war as we remember and respect them. You know how deadly serious we are about ANZAC day remembrance. For us what we sacrificed for the mother country in this war was hard to carry. First up yep the ANZAC Corps was tiny compared and the number of our dead was small compared to everyone else with roughly over 50,000. As a nation we were tiny as well with a small population. When you remove that many males from the breeding population crippled our growth as a nation and we were only starting to recover as WW2 broke out. After that to recover we offered assisted passage to the people of Europe to immigrate to Australia. We were still in negative population growth until the late 60’s.

Compared to the other nations our contribution was small but it nearly broke or backs trying to carry it. So yes we are proud of what we pulled off and hold the men and women how actually did it dear to us. Each generation that followed faced the same question. Did we do enough and right enough to stand in their grand company.

I grew up in the aftermath of their sacrifice and I see them as the greatest Australians, but they are real men and women to me. Sadly they are falling into legion now and each new generation today is making them bigger, taller and tougher. The younger generation growing up now live their super heroes and try to see them as such. I prefer to remember Harold Evans. He left a young wife and toddlers behind. All he wanted was a small farm to raise them and he was afraid of frogs. His wife remarried to an abusive man and committed suicide in the mid 30’s after one bashings too many. That is how I prefer to remember them and not as 8 foot tall men of steel that destroyed everything in their path.

Oh man, @jamesevans140 – yes, I do see that big post now and have responded. Yeah, it it’s not tagged @oriskany I may not see it at first, especially if it’s on an older piece of content. That was an epic post you added! 😀