Armistice Centennial: The Final Days Of The Great War Part One – The Hundred Days

October 29, 2018 by oriskany

Here at OnTableTop, we play wargames for fun. Yes, even the dourest and grim-eyed historical grognards have been known to crack a smile at the gaming table now and then.

Armistice Centennial: The Final Days Of WWI Interview

That said, there come occasions when we should take a reflective pause, a quiet moment to genuinely remember that for too many people, this was not a game.

I respectfully submit that this is one of those times.

November 11th, 2018 marks the centennial anniversary of the end of the Great War, the Armistice that ended the “War to End All Wars.” Still observed as Remembrance Day, Armistice Day, or Veterans Day, it endures as a sombre touchstone when we remember those who served not only in World War I, but all wars of the past century.

At the time, World War I was the greatest conflict humanity had yet seen, and wars this big do not end quietly. There was chaos, controversy, complications, and consequence echoing long into future decades. It can be argued that every war’s end sows the seeds for the next one, and rarely has this been brought to starker relief than November 1918.

In this article series, we’ll take a look at the final desperate battles, offensives, and campaigns of that momentous autumn, and make a humble effort to bring just a sliver of these tectonic events to the gaming table.

1918: An Overview

After four years of unprecedented, industrial-scale butchery, 1918 would be the last year of the Great War. Yet this year would also see tumultuous swings in fortune shift rapidly between the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire), and the Allies.

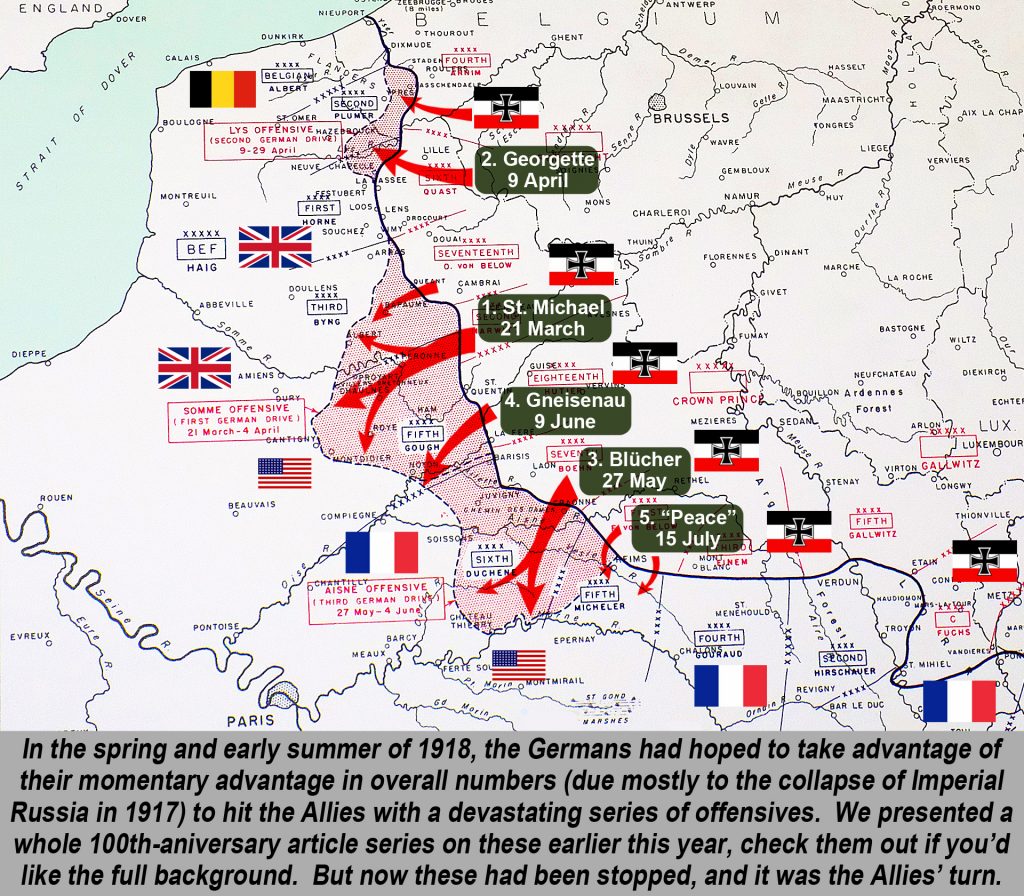

At the beginning of 1918, Germany seemed to have the upper hand. Imperial Russia had been knocked out of the war by the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, freeing millions of German troops to fight Britain and France on the Western Front. Conversely, newly-arriving American armies were not yet in a position to have a decisive impact.

Thus, German commanders (Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff) launched a series of huge offensives from March through July 1918, including the St. Michael, Georgette, Blücher-Yorck, Gneisenau, and “Peace” Offensives.

Fighting had been nothing short of apocalyptic, and casualties skyrocketed into the hundreds of thousands on both sides. British, French, American, Belgian, Australian, Canadian, even Portuguese lines had buckled but held, and by mid-summer these German armies were a spent force.

As the last German offensives withered, it became clear to Allied commanders that the advantage had shifted their way. German losses have been catastrophic, and they’d lost their numerical edge. American armies were now also in position, gaining in both strength and experience, and quickly tipping the balance further against the Germans.

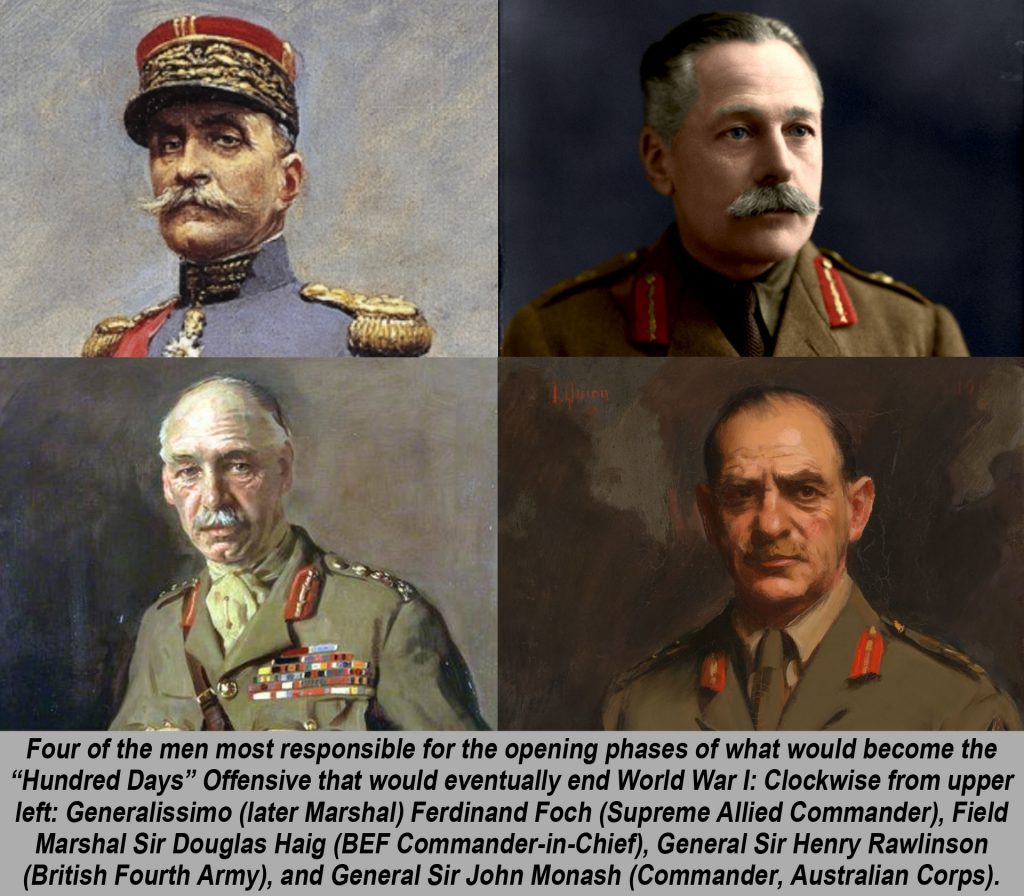

By the middle of July, strong French and American counterattacks were already shoving the Germans back in certain sectors, most notably the Second Battle of the Marne. Allied Supreme Commander (Generalissimo Ferdinand Foch) followed up with the Battle of Soissons starting on July 18, which quickly unfolded into another major Allied success.

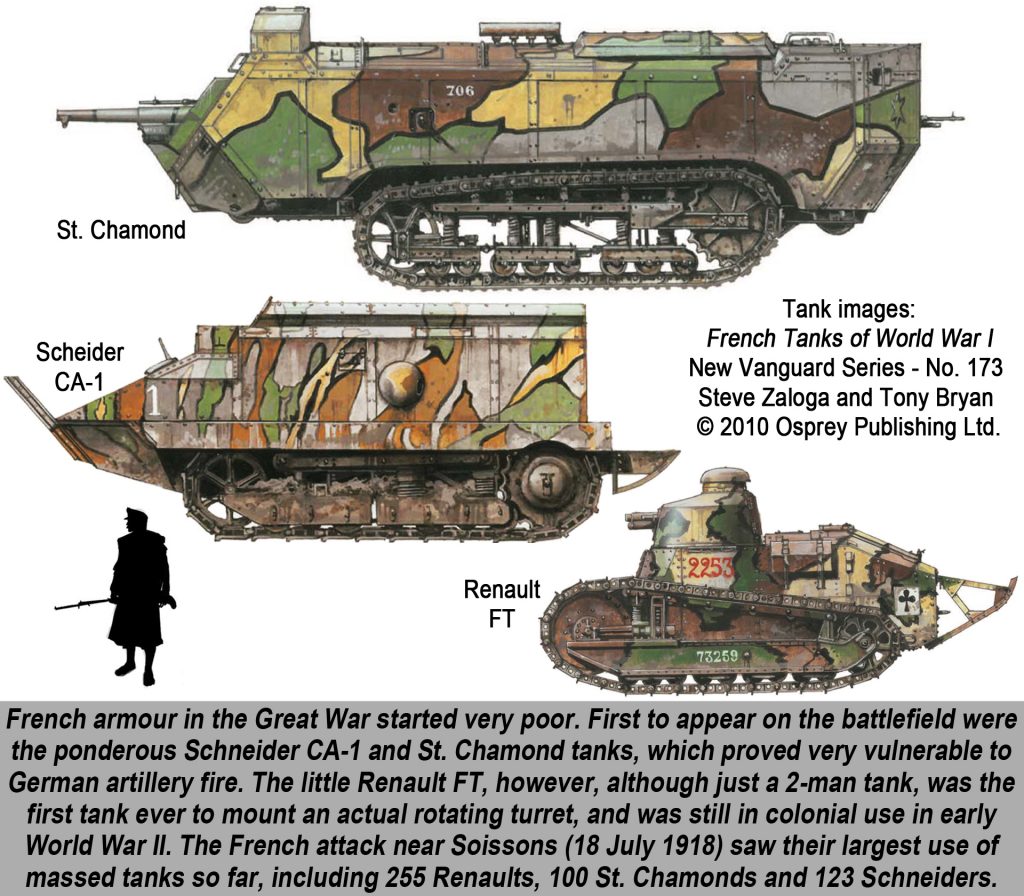

The Soissons attack was spearheaded by hundreds of French tanks, backed up by ten American and two British infantry divisions. The battle was a costly one but won back most of the ground the French had lost to the German Spring Offensives. Foch was made a Marshal of France for his victories at Second Marne and Soissons.

Yet Foch would not be the only soldier rewarded for his performance during this battle. On August 4th, 1918, a twenty-nine-year-old Austrian “Gefreiter” (lance corporal) fighting with the 16th Bavarian Reserve Rifle Regiment was also awarded the Iron Cross First Class for courage under fire. His name was Adolf Hitler.

Eager to capitalize on their victories at Second Marne and Soissons, Allied generals (Marshal Foch for the French, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig for the British, and General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing for the Americans) agreed to open an expanded series of coordinated offensives extending through the rest of summer, 1918.

Battle Of Amiens

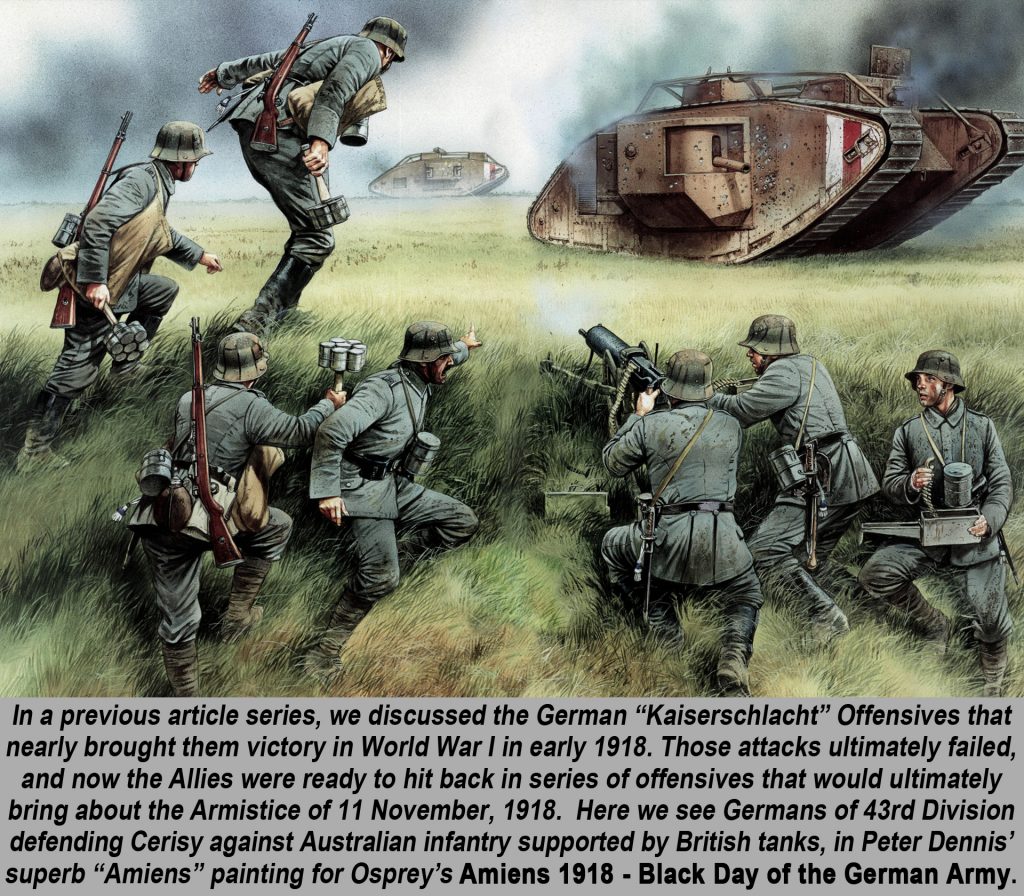

While the French and Americans had been winning at the Marne and Soissons, British Field Marshal Haig was already drawing up his plans for his own counterassault in the Amiens sector, where the Germans had hit the British with everything they had in the “St. Michael” Offensive in March.

The British had held this mightiest of all the German 1918 attacks...barely...in a series of bloodbath defensive battles near Amiens and Villers-Bretonneux, where history’s very first tank vs. tank shootout had taken place on April 24th. Yet now the British stood poised to hit back, and eliminate this “Amiens Salient.”

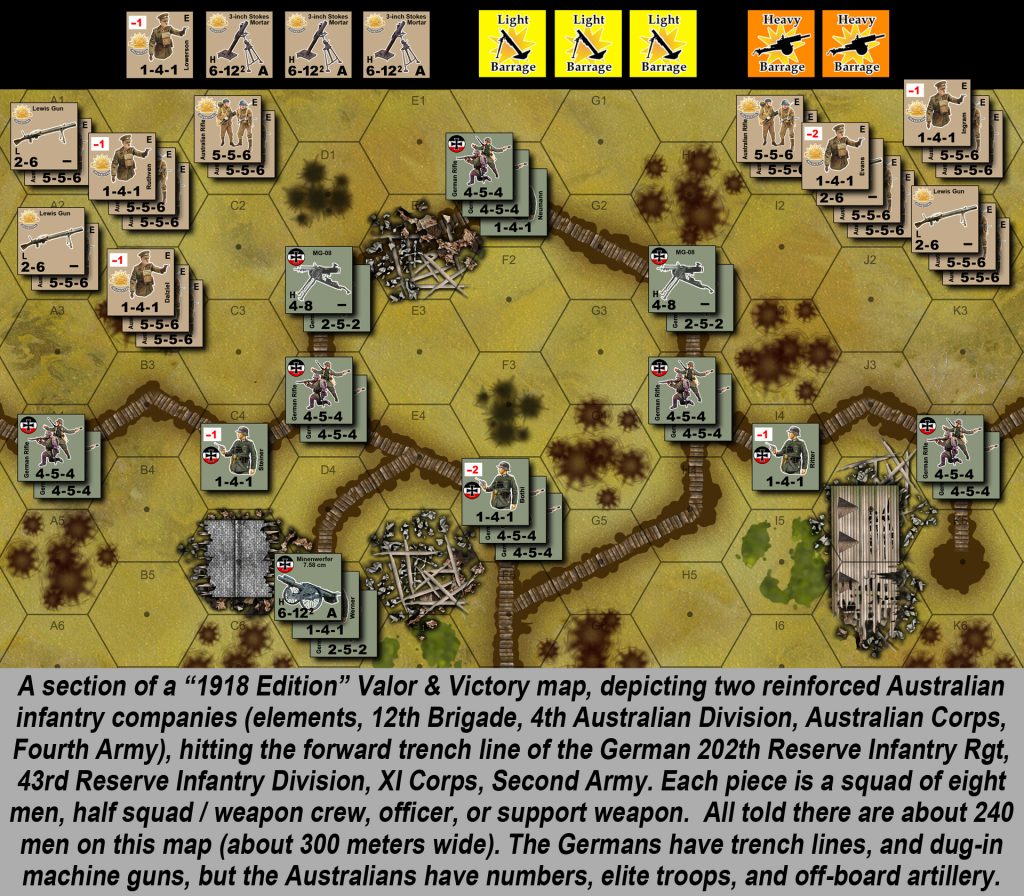

As early as July 4th, the commander of the Haig’s Australian Corps, Lt. General Sir John Monash, had launched successful counterattacks against German positions at the Battle of Hamel. Dispensing with traditional massed artillery, the Australians had instead employed surprise, aggressive infantry tactics, and innovative coordination with British tanks and artillery.

The results of these new tactics, plus further recommendations from Monash, had been passed to Haig and then to Foch, Supreme Allied Commander, who gave the go-ahead for a front-wide assault using a similar model. The hammer fell in the pre-dawn hours of August 8th...now officially recognized as the beginning of the “Hundred Days.”

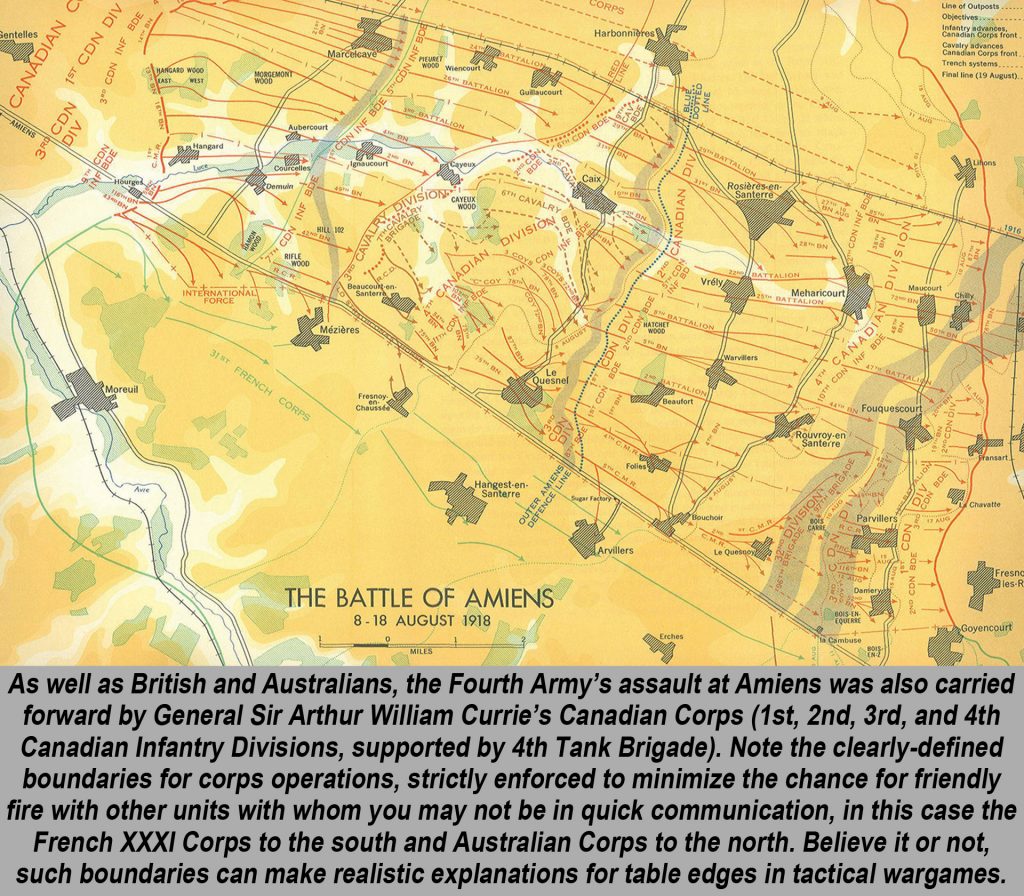

Haig’s attack was spearheaded by Fourth Army (General Rawlinson), led in turn by the Canadian Corps (General Sir Arthur Currie) and the Australians under General Monash. Each of these corps was supported by about 150 Mark V and Mark V* trench-crossing tanks, along with a cavalry corps with about 100 lighter “Whippet” tanks.

The results were stunning. After years of stalemate, the German front split wide open. Although tanks and artillery had been used to support infantry assaults many times over the past two years, this time the close coordination of these arms delivered an overwhelming tactical victory and nearly immediate operational breakthrough.

So thorough was the Australian, Canadian, and British victory at Amiens that German General Erich Ludendorff would record the opening day of Amiens as “the black day of the German Army.” For the first time, whole German units simply fell apart on the battlefield. A psychological, as well as military turning point, had been reached.

Part of the reason stems from the state of mind of the German soldier. By 1918, Germany had suffered four years of not only war but naval blockade. The men knew their families back home were starving. They were starving themselves and had poor supplies and medical care. New recruits (when they arrived) were depressingly young.

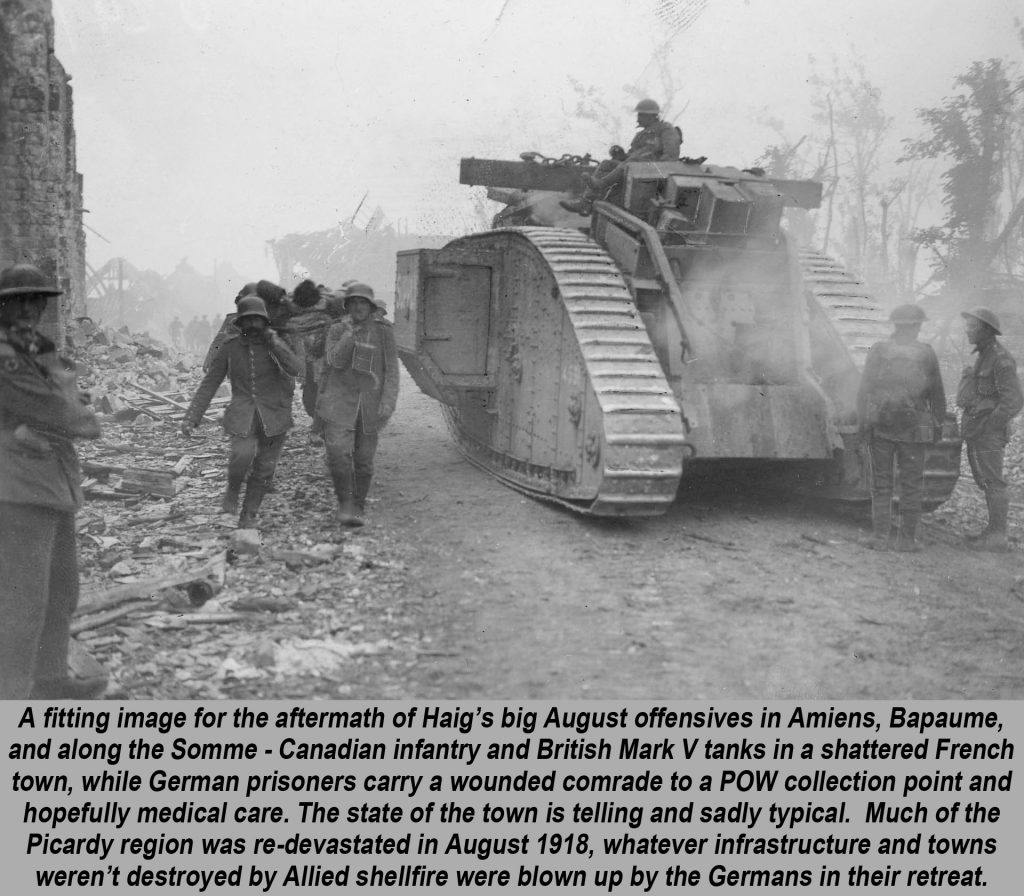

Nevertheless, Allied progress at Amiens soon slowed to a grinding, bloody crawl, thanks less to German resistance than to Allied infantry outpacing their own artillery and slow, creaking, mechanically unreliable tanks.

On 15th August, French Marshal Foch requested that Haig gather reinforcements and continue this successful Amiens attack. Haig, however, refused, recognizing that the shock along the Amiens-St. Quentin sector was spent. Rather, he activated his Third Army and opened a new attack to the north, sparking the Second Battle of Bapaume (sometimes called the Third Battle of the Somme).

Old Battlefields, New Victories

Haig’s new offensive opened along the general Albert-Cambrai west-east axis on 21st August 1918. The British Third Army would strike northeast just off the northern shoulder of the successful Amiens attack discussed above.

This was actually the third engagement to rage across the Picardy countryside of northern France. The most famous Battle of the Somme had burned for 140 blood-soaked days in 1916. The Germans had then stormed through with their Spring Offensives in March 1918. Now the Allies would retake these fields again...for good.

As at Amiens, there was no lengthy artillery barrage preceding the attack - only a sharp, accurate, and devastating salvo immediately before a closely-coordinated infantry and tank assault. Initial objectives included the Albert-Arras railway line, the loss of which would hamper German ability to bring in reinforcements to stabilise their defence.

The Germans mounted a brief counterattack on August 22nd but were quickly defeated. The British offensive soon expanded, drawing in elements of the First Army from the north and the Fourth Army from the south. By August 26th, Ludendorff bowed to the inevitable and began a well-ordered withdraw to better defensive ground.

This withdrawal, however, was frustrated by a New Zealander attack at Bapaume, by Australian troops capturing Mont St. Quentin and the town of Péronne, and Canadians who cracked the German line wide open at Drocourt-Quéant.

These setbacks forced the Germans to give up any idea of a defensive line along the Somme, and fall back further to the so-called “Hindenburg Line” (as known by the British, the German name was Siegfried Stellung, or the “Siegfried Position”).

This was a fortified line built in 1916-17 to protect the territory they’d taken in France and Belgium and maintain it as a buffer zone against possible Allied counter-invasion into Germany. This was also the line from which they’d struck with their “Spring Offensives” of March-July. Now they were right back to where they’d started.

This Is Only The Beginning

The Allies, however, pressed the advance. As we’ll see in Part Two, the French and Americans pushed up from the south, opening the bloody Meuse-Argonne Campaign in September. The British, Australians, and Canadians also struck out of the west, opening the Battles of the St. Quentin Canal and the Second Battle of Cambrai.

Further to the north, the British Second Army, together with Belgians under King Albert I, opened the Fifth Battle of Ypres. Here, the battlefields of Flanders and Passchendaele, which had seen such unspeakable suffering through previous years, would finally be claimed for the Allies once and for all.

But we’ll dig into these actions in greater detail in the coming weeks. For now, post below and tell us what you think. Books, documentaries, movies, family connections, past wargames, plans for future wargames, suggest anything and everything that commemorates the centennial of these fateful few weeks.

It’s not every day we mark an anniversary milestone like this one. Don’t let the Centennial of the 1918 Armistice pass without making yourself heard.

Come and take part in the discussion below and follow along with the article series as it develops...

"At the beginning of 1918, Germany seemed to have the upper hand..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"It’s not every day we mark an anniversary milestone like this one..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Following with interest! WW1 isnt really my thing, love WW2 but just never found the same spark with its predecessor. I love the idea of an article series on how the great war wound down though, such a small part of the overall war and something ive never really known anything about but so so crucial.

As usual great job and keep up the good work @oriskany

Thanks very much for kicking us off, @civilcourage. 😀

Indeed, this felt like an article series we just had to do … even on a short time line and in the wake of the Bolt Action Boot Camp.

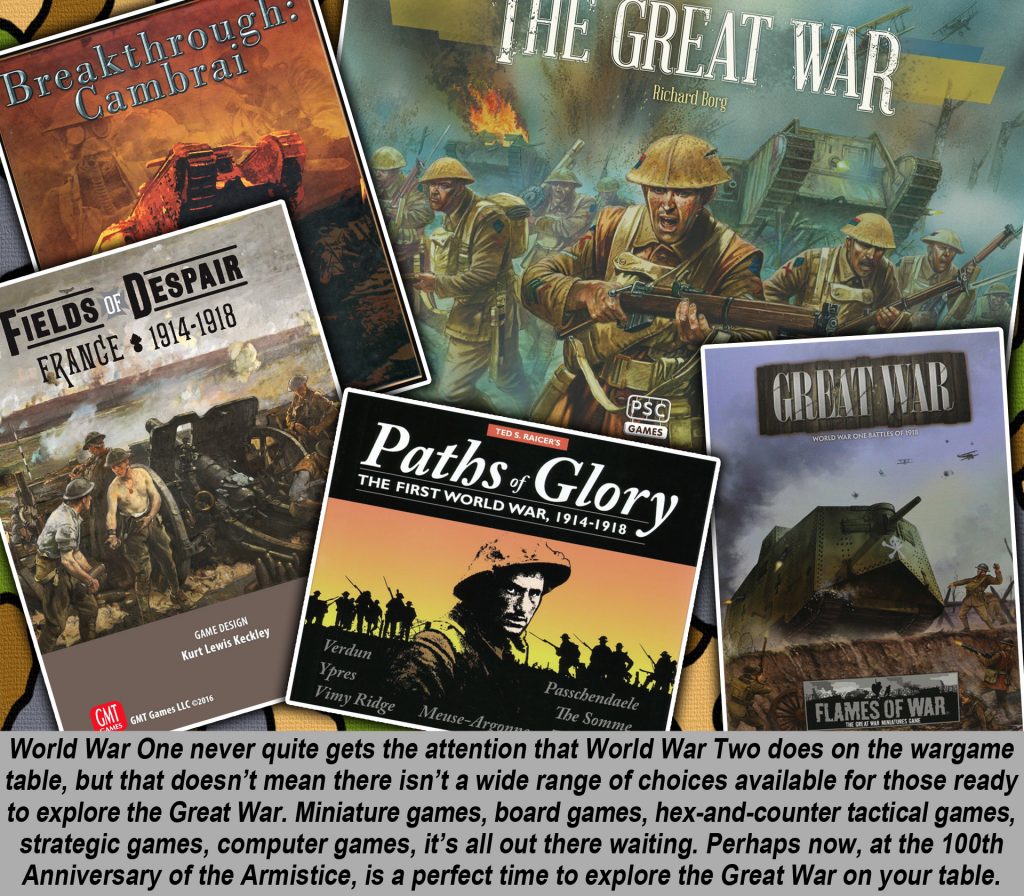

This makes three article series we’ve rolled out regarding the Great War – the Heroes of Limanowa series, the “Kaiserschlacht” Spring Offensive series we did earlier in the year, and now this one. Combined with supporting material like the unboxing @avernos and @johnlyons did for the PSC Great War and French expansion – I feel we’ve done the Great War is deserved justice here on OTT / BoW.

Thanks very much for the kind words and support!

Good opening @oriskany for what looks like will be interesting series, the final offensives of the war tend to be overlooked a lot, most histories tend to get stuck in the muck and mud of WW1.

My Grandad who used to me my go to source on this, didnt know much about this phase of the wars as he was still in hospital recovering from the loss or his eye during the earlier German offensives of March.

Holy crap, @bobcockayne – he was wounded in the St Michael Offensive? I’m assuming he was with Third or Fifth Armies? Casualties among those formations were indeed horrific. But this was also where the war finally started to become a little more mobile – not the “muck and mud” of earlier years as you mention.

You Granddad’s case sounds very representative of the overall state of the BEF in 1918. The armies MOST involved in halting the St. Michael and Georgette Offensive (Fifth and somewhat Third and somewhat Second) were more or less left out of the Hundred Days (Fourth leads off, Third later for Arras-3rd Somme, and Second later for 5th Ypres-Flanders) Losses and damage had just been too high in those units first hit by the Kaiserschlacht Offensive.

This goes for the Irish as well. 36th Ulster took some of the highest casualties of any division anywhere in the BEF in halting Georgette in April 1918. Thus, they were not in the opening of the Hundred Days, 5th Ypres, Advance through Flanders, or any of it, they don’t get re-committed until Courtrai later in October, 1918 … and even then with a largely rebuilt OOB.

@oriskany As far as I know, he never put any locations to his anecdotes, I was only 13 when he died.The one vivid memory is that he did say was the war got more open, and he had been defending a wall area at the edge of a town/Village,(no idea where) and a German platoon tried to get through a gateway and he shot so many that the gateway was full of bodies, he only fell back when they moved round his flank.

Sounds pretty grim, @bobcockayne . Again, also sounds very “St. Michaels.” Germans pushed through a lot of towns and villages in the Amiens sector, especially around Villers-Bretonneux, where the British took tremendous punishment finally halting the German offensive … but also where the Germans took ghastly losses in their all-out offensive. Definitely one of the most intense spots in the war, especially in 1918. This would also line up with the late March-early April dates.

Great start, informative as ever looking forward to the rest.

Thanks very much, @gremlin – glad you liked it. 😀

Nice start Jim

I noticed yesterday that there is a 100 days docu-drama on BBC iPlayer. I did notice that it’s a Foxtel production so I presume that at least in part its an Australian production. Will try and give it a watch this week

Thanks very much, @torros – Speking of Australians – I know the Battles of Hamel and the Australians aren’t technically considered part of the Hundred Days, but this isn’t really part of the Kaiserschlacht offensives, either. The Australians at Hamel and Monash’s contribution to new Allied assault doctrine are very important, and I didn’t want them to “fall between” the this article series and the one we did earlier in the year. So the spearhead at Amiens is actually the second big push the Australians make in the summer of 1918.

Another cracking article Jim, such a poignant but oddly overlooked period of the war (at least in the minds eye of the general public). Incredibly bloody year, but it also brought together years of innovation and delivered some tremendous victories. Remember studying the period when I was reading for my degree. The escalation of the air war was something that always intrigued me, the rapid advance in technology, tactics and strategy – had the war gone into December, Allied air power would have targeted Berlin for the first time. The attacks on the Ruhr, as limited as they were, were none the less terrifying enough for German High Command to divert resources and troops to form makeshift anti-aircraft units. Impact it had on civilian morale far exceeded the almost superficial damage done to the factories in the area.

Great work, eagerly looking forward to the rest of the series.

Thanks very much, @bigdave – indeed German civilian morale (and economic hardship leading to civil unrest and the threat of political chaos) is a huge factor in the end of the war.

We do bring up the larger air operations in Part 02, namely the St. Mihiel Offensive where something like 1430 aircraft are used in a massive effort to support the ground offensive (St. Mihiel is largely remembered as an American ground offensive, but only 40% of those aircraft were American – the rest were British, French, and even Italian).

Thanks very much for the supportive comment, glad you liked the article and hope you like the ones to come!

I think it was Oct 1918 the French and British command were still planning their 1919 offensives so we might have seen full aircraft carrier actions hit targets (probably the Krupp works) in Germany

Pat Storto came out with a 1919 theoretical variant for PanzerBlitz – since tank vs. tank battles didn’t really happen in WW1, they postulated an extension into 1919 just to see how the tech and doctrine might have looked.

a good start to the series @oriskany the first years were bloody slow slogs payed in thousands of lives with little to no gains.

So true, @aorg but as @torros has pointed out, 1918 was the bloodiest year for many of the combatants (definitely the British and Americans).

Yes the generals were going for Brock scencing the end was coming wanted more land/glory to end with.

Indeed both sides, at different times in 1918, were certain victory was “just within reach” … And we’re all the more willing to pay for it.

Its a lot easier when it’s not you’re life on the line back at GCHQ. ?

I actually usually lay the blame for war and the carnage if produces at the feet of civilians. The generals are just trying to win with the tools the civilians have bothered to pay for. The civilians start the wars, and yes, that definitely goes for democracies, too.

it is the politicians that lie to the public so ?

It’s also the public that demands war, @zorg 0 the politicians don’t have to lie to them.

Democracy is the “will of the people.”

Well, people are assholes sometimes. And they often WANT war.

When they can get the news crew’s to exaggerate everything they can take a back seat but they still put the tuppence’s worth in look at Blair an the WMDs complete BS but people swallowed that.

The media is really only responding to the appetite of the people. If the scary war-monger and sex-scandal stories crank up ratings, media will focus on those. This of course presents a certain picture to the public, which naturally self-perpetuates the process.

Ultimately, though, the people are responsible.

For everything.

Period.

Government, Media, Business, the Military, they’re all easy to blame. But leaving aside truly developing nations or true dictatorships (of which there are VERY few actually), at the end of the day these “evil” institutions were responding to the will of the people. This is especially true in free-market economies and especially true in the age of social media.

Very true why spend time researching stories when the can add to small one’s making them sound big. What’s that famous saying humans are smart but people are dumb ?

I think the expression ‘Bread and Circuses’ springs to mind

Perhaps.

“Just don’t come back without the stones.”

– Zorg, Fifth Element. 😀 😀 😀

Lol, love that film.

I had a feeling. 🙂

“Eh, negative. I am a meat popsicle …”

Lol Corbin Dallas.

“The masses are asses.”

Alexander Hamilton (attributed).

Ha.

“A person is smart. People are dumb, panicky animals and you know it.”

– Agent K, Men in Black.

I think this was the one I was think of thanks of that, @oriskany

Too bad he ruins it with some history-butchering right afterwards. 🙁

“500 years ago everyone KNEW the world was flat.”

No, they really didn’t.

People knew the world was round as early as 300-400 BCE, and had even roughly calculated its size.

The Inca leaders calculated the size of earth back when they ruled South America ?

The Greeks figured it out. Eratosthenes, 240 BCE.

I don’t think the Incas were around that far back.

The Incas were 15th century. They were the ones the Spanish beat up

Ii think they went back to the 12/13th century but the Egyptian’s had all the calculations way before Christ was walking about the world an I think a Turkish empire did it even earlier.

Just checked the tinternet I think it was the Hurrian empire I seen a program about a they went back to 3000bc an were advanced they even had concrete before the Roman’s reinvented it.

I did not know that. I just remembered the Greeks had not only realized the world was round, but used the subsequent geometry to roughly calculate its circumference. So the idea that Christopher Columbus discovered the world was round is simply laughable.

Let alone “discovered America.”

Yet he’s still revered over here. Why? He even has his own national holiday. He discovered nothing, proved nothing, and was in fact a genocidal butcher.

One more thing I just don’t get.

Their is probably other civilisations out their we have never heard of that Did the math’s as well ?

There are no “lost” civilizations back there waiting to be discovered. There’s no

“Hyborean Age” outside of Robert E. Howard novels. 😀 We even have a pretty clear idea on what all these civilizations accomplished. The how and why, of course, remain unresolved in many cases.

But sadly for Indiana Jones and conspiracy theorists, and people who wish Aliens might have built the pyramids, there really are no big gaps left in the historical record.

Just massive stretches where we wish we had a helluva lot more detail, admittedly.

It’s probably been mentioned in other articles but this was a learn on the job war. Even with the more open nature of the warfare Britain lost most of it’s professional soldiery in 1914 (The British at this time were still allowing British soldiers who had finished there term of service to leave the army) and the remainder of the territorials by mid 1915. All Britain had left were the first waves of volunteers to try and hold the fronts and Haigh was very reluctant to send them into massive assaults with so little training. He was finally forced into it by the situation in Verdun and all he could really do was try to develop a plan that was simple enough for some civilians who were high in morale but low in skill which led sadly to the massive casualties at the Somme. But as I mentioned before it was a learning war and a few weeks after July 1st the new commanders were leaning and starting attacks from the middle of no man’s land developing short harp artillery barrages developing the rolling barrage which led on to the tactics developed by Plumer at Messines which Monash developed further at Hamel and on to Amiens. The problem facing the 100 days in my opinion was that the majority of British troops involved were facing the same baptism of fire that the original volunteers faced at the Somme in 1916 ie A new wave of conscripts lacking experience of the situation they were heading in to . That plus the tenacity of the German defenders especially at the Hindenburg line was always going to create a high casualty rate

This was absolutely true with the Americans, @torros – that’s for damned sure.

I’m sure it’s also true for the French, Belgians, British, and even Germans in 1914. But my articles have focused mostly on the 1918 battles so I defer to other experts on 1914 information.

I think in a round about way trying to show a reason why the casualties were so High in 1918 as the forces had reinvent their tactics and train almost whole new divisions again to cope with the different type of warfare that the troops were fighting in 15-17

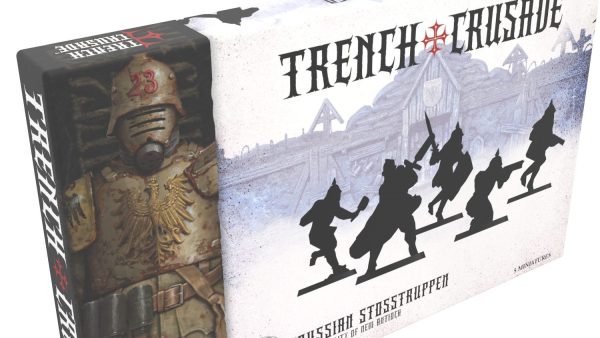

I’d have to agree with that. First the Germans with their revised “stosstruppen” infantry assault tactics and artillery tactics of Georg Bruchmüller (as covered by @neves1789 in our previous series). Then the Australians with their adaptation of these tactics into their own doctrine, adding British tanks … then the BEF adopts these new “Monash tactics” overall via Rawlinson / Haig.

Then you have the Americans, who are just learning tactics at ALL. 🙂 Having a bit of fun there, but not really, German diaries and reports comment on American courage, tenacity, and ferocity … and recklessness.

“These guys are nuts! They’ll REALLY be dangerous once they learn what they’re doing!”

Of course, American units took the casualties to prove it. The 369th “Harlem Hellfigters” and 4th Marine Brigade at Belleau Wood are examples.

That, and whole units had to be rebuilt from scratch not just because of re-training (or lack thereof) but also because of the CASUALTIES taken in these 1916/1917 battles. Many German divisions of the Kaiserschlact Offensives were from the East, where the fighting was very different, the original Western Front divisions had been chewed up at the Somme and Verdun. For the British we have units like 36th Ulster that had to be rebuilt almost to the last battalion in Feb-March 1918. The French were exhausted by fighting all through Verdun, and in the area around the Marne, Ainse, Chemin des Dames, etc … so most of the initial American divisions went to their sector.

Of course, all this would just lead to MORE casualties in 1918.

The article lived up to the interview!!! I am far from a historian and even farther from a grognards. Yet I found this very informative and I am interested in seeing what the grognards do with it. I need to check out the project page to see how the Ulstermen do during this turbulent time.

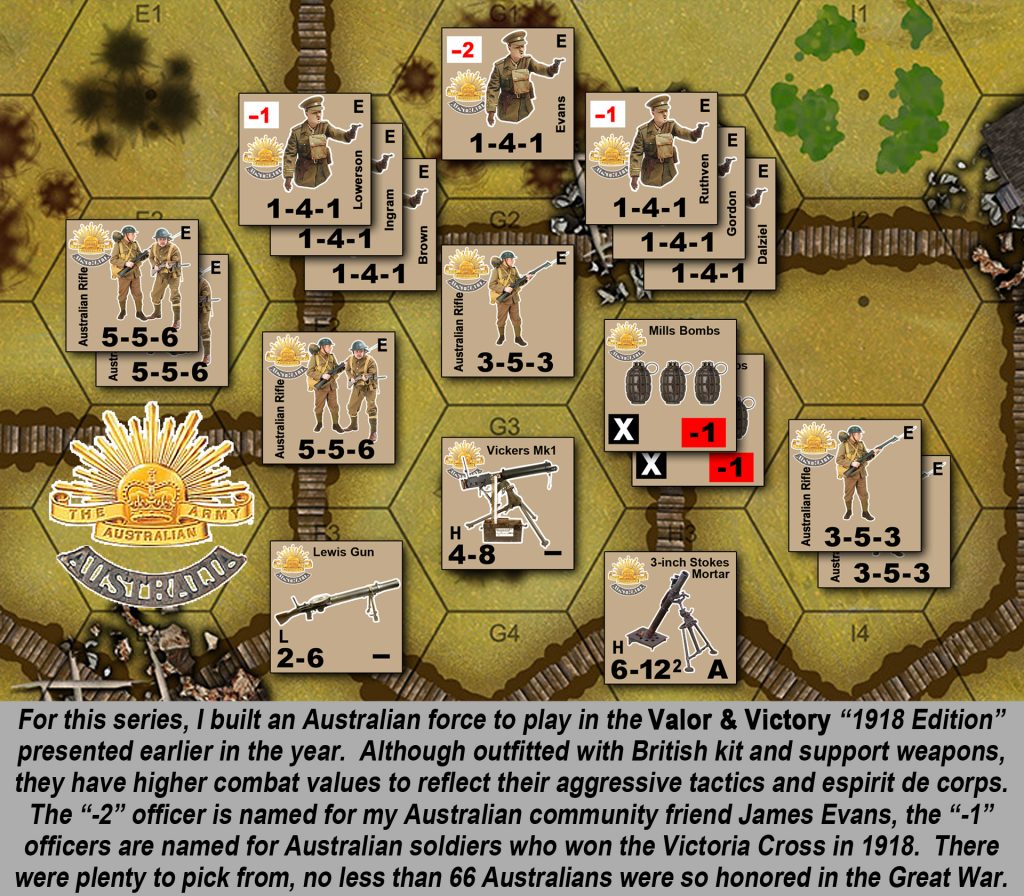

We now have British Mark IV (male and Female) and Mark V (male and female) tanks worked up in that project thread as well. I want to put some British Mark Vs with my Australian infantry and see how they do against German defenders at Hamel and Amiens.

https://www.beastsofwar.com/project/1288632/

Looking forward to read it in details tomorrow

Awesome. I hope you like it @rasmus ! 😀

Another good one up your sleeve, dear @oriskany , thank you for this. I still remember your first series about WW I earlier this year. That was a mountain of information that is useful for your current article series as well.

The war ended on November 11th 1918 at 11.00 o´clock. It is an event that in Germany is not considered as important as it should. Of course they will lay down some flowers at the bottom of the columns reminding of the dead of the war, for instance in the small village where I live, but there´s not much more.

On television, however, there is at least something, but so late that I fear not many people will be watching this, let alone be interested.

A few years ago I watched a documentary about the madness of war, in which they told a story about a British soldier, who died in battle on Nov 11th, 11:05 o´clock, that means, after the armistice. It was a soldier who had been fighting for quite a long while. He went through all this horrors and then this. Arrrgh.

There is a German writer Erich Maria Remarque, who wrote a novel “The Way Back”, and in the first few chapters he describes the end of the war in a German trench. I think it is quite genuine, because Remarque fought in the war himself. The main issue of the novel is the attempt of the soldiers to reintegrate into society. Remaarque also wrote “All Quiet on the Western Front”.

As for the German war against the Russians, still an estimated million men were locked in at the Eastern front. They were there to protect East Prussia against both the Russian army and a probable communist invasion of Germany. Still, I think even with a million more men the German defeat would have been just a matter of time, with all the ressources spent and wasted.

Questions: Would vou consider Ludendorff to be a war criminal?

De Gaulle called the time from 1914 until 1945 as the second 30 years war. Do you agree? With the Soviet/Polish war, the Spanish civil war and maybe more “small” wars that we haven´t yet heard of, de Gaulle´s idea has something.

Looking forward to read more, and please some gaming suggestions.

Thanks, @jemmy ~

This is actually the third article series we’ve done on the Great War, we also had one on the “Heroes of Limanowa” kickstarter last year, commemorating battles on the Eastern Front between the Russians and Austro-Hungarians in the opening year of the war.

Part 03 of our article series lists the last Englishman, Canadian, Frenchman, and American known to have died on 11 November, at least BEFORE the 11:00 AM Armistice.

Of course, these are technicalities, people were dying of their wounds and the Spanish Flu for years after this.

Very familiar with Remarque. Another must-read antiwar novel for World War I is Dalton Trumbo’s “Johnny Got His Gun” – such a scathing indictment of the Great War and its true cost (especially for the 1930s) that the author was wound up being blacklisted.

Well over 1.3 million men were transferred by the Germans from the East to West over the winter of 1918. The estimate is 50 divisions, and remembering how large German infantry divisions were in the Great War (much larger in the Great War than in WW2 – 1914-1918 each infantry division was built on two full brigades of two regiments each, rather than just three regiments plus support assets).

I would agree that German defeat, and sooner rather than later, is still inevitable no matter what happens with the Kaiserschlact roll-out of spring 1918. As we say in the interview, the British naval blockade and increasing American leverage into the war would have eventually forced this decision, if nothing else. Early-mid 1919, tops.

You ask: “Would you consider Ludendorff a war criminal?”

No. Don’t get me wrong, he was a horrible human being, but not a war criminal in my opinion by the general guidelines later laid down at Nuremburg:

Article One: Participation in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of a crime against peace.

No. The closest this really comes is Germany’s invasion of Belgium, which Ludendorff I don’t THINK was involved with (engaged against the Russians on the Eastern Front early in the war).

Article Two: Planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression and other crimes against peace

No. Germany didn’t start World War One. A Serbian shot Archduke Ferdinand and the Russians come to Serbia’s defense, so if you want to get insanely technical, the Russians (i.e., the Allies) start World War One. Maybe the Austro-Hungarians for their crackdowns in the Balkans (technically fired the first shots of the war – MS Bodrog bombarded Belgrade in response to Serbia blowing up the only major bridge across the river Sava which linked the two countries)

War crimes:

No. If you haul up Ludendorff for war crimes, you have to do the same with Paul von Hindenburg.

Crimes against humanity:

MAYYYBE? The closest here is Ludendorff’s counsel to the Kaiser to begin unrestricted U-boat warfare, although British and American practice of deliberately putting war materials on civilian passenger liners dulls this charge if you ask me.

“De Gaulle called the time from 1914 until 1945 as the second 30 years war. Do you agree?”

I refuse on principle to agree with anything deGaulle says – he’s just not a person I admire in any shape or form. 😀

On a more serious note … no. A full two third of the WW2 Axis powers were Allied powers in the Great war. By far the biggest Allied power in WW2 (Soviet Union) was a radically different government than we saw in the first war. Germany really DID start World War Two (they didn’t start World War One), and they started it for very different reasons than the Kaiser went to war in 1914.

I could go into details here, but I would wind up with another article before I knew it. 😀

Thanks for the great comment! 😀

What did he just say? @oriskany is going to prepare another article series? Awesome!

But if he was only joking… then remember the old war propaganda poster: “Careless Talk Costs… 5-Part Historical / Wargaming Article Series, including Maps with Hexes and Stacks of Military Asset Tokens, photos of fully-

painted miniatures, amazing terrain, carefuly reasearched and cross-checked facts, discussions in the comment sections and requests for more article Series…”

OK, like the now famous STAY CALM Poster, this version of the CARELESS TALK poster was held in reserve, in case of invasion…

Thanks, @aztecjaguar – yeah, @jemmy often asks pretty good questions, the kind that can’t be answered in a couple sentences or bullet points. 😀 So in replying to his posts, I often wind up with half an article.

Way to go @jemmy – keep on asking good questions!

😀

Great article. I’m going to dig out my minis for a trench raid game in a couple of weeks. Skirmishing into enemy trenches with what resembled medieval weaponry at the same time new tech such as tanks are used. Strange how there was space for both types of warfare.

Very true, but when you’re face to face with the enemy, a sharpened entrenching tool doesn’t need reloading…

Thanks very much, @denzien – we did a pretty serious interview with general gaming tips on the Great War, with a focus on trench warfare (and how to best bring them to the tabletop) you might find interesting:

https://www.beastsofwar.com/featured/trench-warfare-tips/

We’ve also run some very heavy trench assault games in Valor & Victory: “1918 Edition” – especially a German “stosstruppen” assault into the teeth of French trenches (Blucher-York Offensive, May 1918)

https://www.beastsofwar.com/project/1208696/

Not sure if you’d find them useful, but maybe interesting. 😀

Very true, @damon – US Marines didn’t call the e-tool the “lobotomizer” for no reason.

It often had a jagged, serrated edge … for *ahem* “cutting foliage.”

Yeah, sure.

Great article as always, it’s good to see the follow up on our previous work. I also enjoyed the interview earlier this week, there was some good insight there for people with more limited knowledge on the topic.

The way you guys interpreted and talked about the loss of WWI was nice to hear, it being in a more classic funerary way. Here in Belgium (or in Ieper at least) the entire commemoration is set up very artfully (modern sculptures, lightshows, abstract theatre,…). In a way it’s a method to draw more people in but on the other hand, it at times feels forced and not at all sincere or truthful to the memory of those who died. It feels very conflicting as it’s good that more people are aware of the commemoration but it’s not happening in a way that is meaningful to me (and a good deal of other people I can imagine). How’s the commemoration happening in the US?

I realise this might sound a bit sanctimonious but I always preferred visiting Ieper and Zonnebeke and the Somme regions before the 14-18 commemorations. I felt more connected somehow

Agree. Avoid big crowds led by self-congratulating chest-thumpers.

Oh absolutely. I’m sure that more solemn atmosphere will return once the centennial is over and there isn’t such a drive to commercialize everything.

When we went to Normandy for the 70th Anniversary, we deliberately waited until well after June 6. Even then, certain places like Ste. Mere Eglise were pretty over-commercialized. It’s like a mini EPCOT center, very sad. Skip Ste. Mere Eglise, check out Ste. Marie DuMont instead.

Thanks very much, @neves1789 – I was actually hoping you’d show up. 😀 Made sure you “got your props” in both the interview and in the comment thread of this article. 😀

We have no real commemoration happening here in the US, at least not I am aware of. We’re terrible with our history. I mean, our company has changed policy and we get Veteran’s Day off from work (November 11). Honestly our nation at the moment is cranked up with midterm elections November 6.

Yeah I noticed, thanks ^^

Too bad it’s not very commemorated, although it’s somewhat understandable with the US not being majorly involved (at least compared to the UK, France etc.) It’s a national holiday here, which we and my friends mostly celebrated by playing wargames 😀

The least I could do, @neves1789 . 😀

November 11 is actually a national holiday here, too. Although we call it “Veterans Day” and its to commemorate all people who’ve served in the military, not specifically for the November 11 Armistice.

Personally, I wanted to just put out this series. 😀

We’ll also have a podcast / possible Weekender XLBS segment coming out on Sunday November 11 itself. So if you watch it on Sunday morning, European Time, we’ll be commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Armistice almost to the exact hour. 🙂

I found this article quite interesting:

https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2018/10/why-first-world-war-was-no-waste-0

Thanks for the link, @damon .

Interesting article. He makes some very interesting points about the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. We touch on these these points briefly in Part Three.

Another great read @oriskany ! Thanks for putting this together.

Thanks very much, @cpauls1 – indeed, this was a date we just couldn’t miss.

I’m hoping to try out my British Mark IV and V tanks later today (with Australian infantry support) against entrenched Germans at the Battle of Hamel, or maybe the opening of Amiens. (Valor & Victory, “1918 Edition”).

Great article @oriskany finally got a chance to read it.

In a few WWII Memoirs I’ve read they talk about Desert Veterans being put off/paranoid when fighting in the Bocage of Normandy and having to basically re-learn a lot of tactics.

I wonder if the same thing happened in WWI when the soldiers left the trenches/mud and started fighting in towns and fields.

I’ve only played two WWI Wargames. Flames of War Great War is great and it will transition very well to v4 so I’m eager for that.

Warhammer Historical: Great War is the other and it’s brilliant. It’s technically a Battalion Level games where One 28mm Mini represents 2-3 men but if you play it at 1:1 Scale then it’s Company level. It’s apparently based on 3rd or 4th Edition 40K.

My local Wargaming Groups Historical expert once told me that if you’re going to play WWI on the table top you need to either play 1914-15 or 1918 because anything in between just gets way to messy and complicated for a 28mm Table.

Thanks @elessar2590 – but eh … What the hell? Warhammer / GW has a WW1 game? And it’s command-tactical? (one mini = more than one man)?

And it’s GOOD?

Is this real life? Did I fall down? 😀 😀 😀

That sounds amazing!

Indeed, we covered the Flame sof War Great War 1918 in more detail in the previous series, for two reasons. The main supplement book for that is Villers-Bretonneux – a battle we SPECIALLY cover in that earlier series. Also, @neves1789 and his friend Erik had awesome FoW WW1 armies we were able to use for the photos, and of course Sven also wrote half of those articles as well.

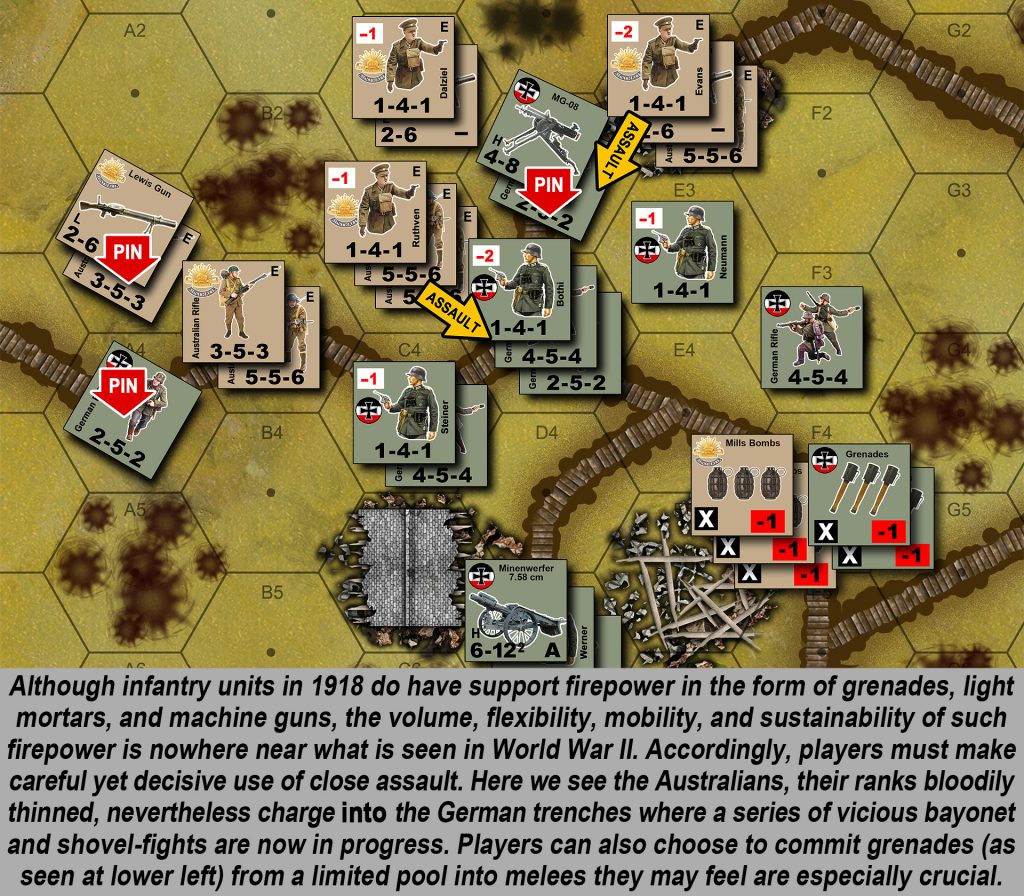

When it comes to wargaming WW1 … here is the mother of all pitfalls and what you have to watch out for.

There’s almost no such thing as a World War I wrgame.

Really, there isn’t.

What there is is some abundance are WW2 games re-skinned for WW1. And there’s the danger.

The weapons are so similar, the IMMEDIATE effects and abilities are so similar, that it’s tempting to just say … oh, the British had 76mm mortars in WW2, and also in WW1. Same weapon, same stat line, same rules.

WRONG.

The tactics, doctrine, communications, training, support infrastructure, these are where the really massive changes take place between late ww1 and early ww2. Not in the weapons, in the way the weapons work.

WW1 is going to put a LOT MORE RESTRICTIONS on what you can and can’t do with your “WW2” weapons. So what a lot of WW1 games really turn out to be … are WW2 games that people are familiar with … except many of your favorite tactics and tricks are now illegal. This gets on peoples’ nerves, they discard or ignore the new rules, and voila … you’re back to playing WW2 mechanics with a WW1 coat of paint on it.

Don’t fall into that trap. Use those “annoying” constraints to really put yourself in the boots of a WW1 commander, and overcome the challenge of accomplishing your battlefield mission DESPITE the technical limitations of your firepower and mobility.

I did own Warhammer Great War. From memory it was one figure= 1 man each with its own stat line and from memory it was just a 40k reskin with some special rules thrown in. Personally I didn’t think too much of it. I never owned any of the supplements so that might have changed things dramatically rules wise

I had honestly never even heard of it. Not surprising, though. What few GW tables I’ve ever seen often have a WW1 look and feel to them especially with the armored vehicles. Then again, GW and 40K is a very “British” thing. It’s never been as dominant here in the States.

@oriskany I think this discussion has come up before Rules wise in the main I agree with you but there are some excellent higher level games out there

Indeed. @torros – I was discussing “Level One” tactical wargames here, not “Level Two” command tactical games, “Level Three” operational games, “Level Four” Strategic games.

“Dispensing with traditional massed artillery, the Australians had instead employed surprise, aggressive infantry tactics, and innovative coordination with British tanks and artillery.”

I am interested to learn more about these innovative Australian offensive tactics.

I think @oriskany mentioned in the Interview that the Australians used tactics based on – or similar to – the German stormtrooper tactics for attacking specific sections of trenches. Did the Australians kind of “scale up” these tactics and use them simultaenously along hundreds of miles of the front line?

You hear or read mentions of concepts like “combined arms”, “fire and manouver”, “Pincer Movements”, and so

on. What would really help, would be @oriskany prepare and present these various military Tactical concepts – like he did with the various ways a Platoon can advance in formation. (All of which showed how absurd war films are that depict soldiers all bunched up or strolling down the middle of a road or over the crest of a Hill with the Officer at the front…)

Anyway, thank you for Part 1, looking forward to Parts 2 and 2.

@aztecjaguar – in basic terms, the innovations to Allied (or at least BEF) tactics proposed by Monash and proved at Hamel (4 July 1918) can be summarized as such:

Dispense with the massive, prolonged artillery bombardment. Artillery is not a “destructive” weapon, it can’t be expected to blow a hole clean through enemy positions so your infantry can storm through with little or no resistance.

All these very long artillery barrages really do is provide the Germans with ample warning as to precisely where you intent to strike.

This allows the Germans plenty of time to bring up a second line of divisions 5-20 miles behind the line of contact (out of range of your artillery) so that, if your assault DOES crack the line by some miracle, they can immediately counterattack and seal the breach.

In effect, you trade a very small tactical advantage (if any at all) for an overpowering OPERATIONAL flaw.

NEW IDEA: Artillery is a SHOCK weapon. It doesn’t really kill any units in a tactically meaningful way, but pins them down for your assault. Hit the enemy with artillery very very hard … but only MINUTES before your assault goes in. Yes, you will do much less damage. But were you really doing any damage to begin with? And now you have surprise. The Germans don’t have the hours, days, or even weeks needed to move whole new reserves (divisions or corps) into your projected axis of advance.

The real “destruction” of the attack is delivered not by artillery or mass firepower, but hardened assault infantry specially equipped and trained for the task. Australian infantry, with a certain proportion of every company, regiment, or division raised from hardened “Outback Stock”, proved ideal for this kind of work.

So this is the part of the tactic that the Australians, especially Monash, saw the Germans use (especially in the St. Michael and other Kaiserschlacht offensives) and adapted to their own needs.

What Monash really added was the close cooperation with British tanks. The Germans, despite all the video games and movies that feature A7Vs, really didn’t have tanks in a meaningful way. The Allies, by contrast, used something like 300+ tanks just at Hamel, and 400+ more at the opening of Amiens (8 August 1918).

Infantry without tanks are terribly vulnerable, and can’t break through wire, trenches, etc.

Tanks without infantry are terribly vulnerable, the German VERY QUICKLY lost their fear of them and found they could be easily knocked out with whatever field artillery happened to be at hand.

Tanks WITH Infantry close at hand … is a tough combination to beat. Especially with that very short, sharp, and intense artillery barrage leading off that delivers the most important battlefield advantage of all …

Surprise.

That’s the “Monash Playbook” in a generalized nutshell. It all sounds very elementary, but that’s because we’re mostly accustomed to wargaming in WW2, where such tactics were already 20+ years old.

AT THE TIME this was novel, and hey … SOMEONE had to do it first. 😀

Now I understand – thank you so much for the comprehensive explanation – all kinds of awesome!

Monashs tactics to me were the culmination of developing infantry and artillery tactics from the previous couple of years The final piece of the puzzle that Monash added was the addition of aircraft into the equation. Not only as close support which had been used before but bring used in a resupply situation for the infantry especially in things like Lewis gun magazines

No worries at all, @aztecjaguar . And again, I can really only go into it in summary. But those are the basics.

“The true role of infantry is not to expend itself upon heroic physical effort, not to wither away under merciless machine-gun fire, not to impale itself on hostile bayonets, but on the contrary, to advance under the maximum possible protection of the maximum possible array of mechanical resources, in the form of guns, machine-guns, tanks, mortars and aeroplanes; to advance with as little impediment as possible; to be relieved as far as possible of the obligation to fight their way forward.”

Lt. General Sir John Monash

Ok late to the party as usual. Thanks for the honour of the name sake @oriskany. I had relatives here, mostly privates and they spoke very little of it.

Monash is about as close as I come to being a hero to me. Not because he is Australian and I do have some strong criticisms about him. To me he has the right to stand tall among the tank generals of the next war. Hamel stands as a strong contender for the first modern battle, ST Quentin Canal even stronger. Yet Australia would not become a nation invested in tanks.

Coming into Hamel Monash had two issues that had to be addressed.

First off all, Australian soldiers thought very little of the tank. Up till now the tanks were not there when needed and caused casualties for their failure to support them. There was some jest among the lower ranks of sending a greased up tank back to England with instructions to the designer on where to place it.

So Monash needed this battle to get the Australian soldier to trust the tank.

The second issue was that he was given four companies from the US 33rd Infantry division and entrusted by General Pershing to turn these men into veterans so they may impart their experience to the rest of US army. Pershing was trusting Monash not to simply use these men as cannon fodder and call it training.

Historians from overseas tend to look at this battle and rant on about the combined arms with tanks and declare Monash a genius, yet they miss the point entirely of what happened at Hamel and the man himself.

Monash was a man who could quickly see a problem before others could see it and by the time they were aware that there was a problem, he already had a number of solutions ready to go.

Monash would conference with his officers during planning, not only instructing but listening and implementing their input. Much like a modern business meeting. Once the final plan was decided then all the way to the lowest ranks knew their objectives.

For the battle each of the US companies were assigned a veteran officer, I believe from the ANZAC 2nd Div, to command and instruct. Then each of the US company’s were assigned to an ANZAC battalion. These companies were not assigned to the first wave, which came as a surprise to the American soldiers.

Prior to the battle Monash used aircraft to bomb the German trenches along with artillery bombardment towards Ville. He used this to cover the sound of the tanks amassing at their departure points so the Germans were completely unaware that we had tanks. He did his best to allow the Germans to deduce that Ville was our target and not Hamel. This would include several diversionary attacks on Ville and north of it towards the Somme. The main diversionary attack was against Ville itself by the 15th Brigade of the 5th Australian division taking 142 casualties. The Germans knew we were going for the Somme via Ville.

For the battle of Hamel, Monash had scout planes flying forward of the moving front lines updating maps of strong points that had revealed themselves and areas where the Germans were concentrating for counter attack. These maps were dropped were dropped near Monash’s HQ and they were snatched up by couriers who delivered them to the HQ. Any strong points or areas of concentration were quickly made the targets of the artillery, made up of French, English and Australian guns.

Monash also had telephone lines ran out to the front line so officers could report the situation directly to him. Monash would assign resources to support any new changes.

So for the first time we have a GHQ running almost in real time.

Many Australian soldiers had a large triangle reflector attached to their backs. This allowed Australian artillery officers in the rear to see where they had reached in the battlefield. Australian controlled creeping barrages moved at the pace of the infantry and not to a timed increment, that was the normal practice of other nations at the time.

These reflectors were also used by aircraft to identify our positions so they could drop ammunition boxes and medical supplies to these forward positions.

Months before this battle Monash was at the demonstration of the new Mark V tank. He believed it better than previous versions and were outstanding in two areas. It was far more reliable and believed immune to the German “K” anti-tank round that was used by artillery units. He also selected the much longer resupply tank. These resupply tanks were put out into harms way keeping supplies up to the front line during the battle. In this effort the soldiers believed that just 2 resupply tanks did the work of hundreds of men trying to bring supplies up to the front line under fire. The loads of the resupply tanks may have been less, but it all got to were it was needed, when it was needed.

The Mark Vs were used as well reported to lead the infantry onto their objectives for them to be easily taken.

I am not saying it was easy by any measure as to achieve this we took some 1400 casualties while the Germans took 2000+. We took 1600 prisoners, 200 trench machine guns and mortars, plus anti tank weapons. What was outstanding is we did all this while achieving all objective in barely over 90 minutes, a true achievement for the times.

It can easily be said that many fragments of this battle plan had been used before and indeed they had. However this is the first time they were all used together as a synchronised holistic plan.

We also consider Hamel a victory for the green US infantry. They did their bit and did not break, but at the cost of 176 brave lives. Above all they earned the right to be mates to the Australians.

The Australians on the other hand became mates with the tank. Monash had achieved all he had planned for.

The Hundred Days while we were there and did the hard yards, it also eclipses us. On 5th October we fought the battle of Montbrehain, our last battle on the Western Front. After this we were a spent force. We had given the best we had and it was not enough. So as the French, English, Canadians and American forces went on to finish the job, we could only watch from the rear as we were rested and being rebuilt.

So that is why the Hundred Days is not an easy fit for Australia, we were the ones who did not cross the finish line. This not finishing something does not sit well with the Australian way. For the Australian generations that were connected to this event speak proudly of what we had done but don’t believe we can stand in the lime light of the other nations that crossed the finish line.

Years ago I was challenged by an Englishman I worked with. He said the way you Australians talk you would think you won the first world war, when it was us. I replied no it was you and a few others that won that war, but we didn’t. We were the smallest army on the Western that reclaimed 25% of the ground that lay in between, so you do the maths. All I was saying in a rather pointed fashion is that we just helped lay out some of the ground work for final victory. We tend to quickly forget that no one really wins a war, it is just that they did not lose as much as the other side. For all our efforts we got WW2 as our prize.

I forgot to mention that the 4th July was chosen by Monash in honour of the Americans now under his command.

Man, that is a serious post, @jamesevans140 –

Meanwhile, the Battle of Hamel (or at least a small part of it) is “underway” in the projects page – hopefully to finish up today.

https://www.beastsofwar.com/project/1288632/

I certainly agree about the magnitude of Hamel’s contributions. Far beyond the immediate effects of Hamel, his “doctrine” was adopted at least in pat up through the rest of Fourth Army and then the BEF, leading to larger victories starting with Amiens and carrying forward through the rest of the Hundred Days.

I might add that in addition to Australian infantry’s distrust in the tank as a weapon or piece of technology might have been a distrust of their British crews. Gallipoli had led to a certain degree of resentment that hadn’t fully subsided, and if I remember correctly this would be the first time the Australian Corps would fight together as a unified formation on the Western Front under Monash’s command.

Indeed, Americans did fight under Australian command here. Americans were being salted across British, Australian, and especially French divisions for acclimatization into real combat conditions. Cantigny, Château-Thierry, and Belleau Wood are all good examples leading up to Hamel.

“Historians from overseas tend to look at this battle and rant on about the combined arms with tanks and declare Monash a genius …”

I’ve even seen one article call him “the Father of the Blitzkrieg.” Clearly someone needs to re-read a few books and rediscover what the name Blitzkrieg actually means.

My impression of the man seems to be of a much more pragmatic and practical problem solder, as you say. An honest, no bullshit assessment of what HADN’T worked in the past and a willingness to break with these preconceptions.

Thanks very much for the details on Prior to the battle. I realized surprise was a massive part of his plan but wasn’t aware of the diversionary attacks. Increased flexibility of artillery targeting and timetables I did know about, and is something we have already incorporated into our Hamel game.

The Mark V was indeed a much scaled-back result of what had started out as a far more ambitious design and improvement over the Mark IV. In game terms, the Mark V seems very similar to the Mark IV. I feel this can be something of an illusion. We’ve added a little more armor to the Mark V (as you may see on the project page), perhaps a little more than the actual historical increase,m but we wanted that up-armor to be evident in the game system, so we may have cranked up the resolution on that one a little. We also gave it one extra movement point. For the reliability different we are retrofitting UN-reliability rules back into the Mark IV, and not applying these to the Mark V.

I understand what you mean regarding the Hundred Days and Australian Corps not being in the front line. The reverse is true for some of our other highlighted units, like Northern Ireland’s 36th Ulster Division. They’d taken such casualties absorbing some of the St. Michael and Georgette offensives that they were not involved in the opening of the Hundred Days, but were only re-committed later for the closing stages after having been rebuilt. The same could be said for 4th USMC Brigade (5th and 6th Regiments) after Belleau Wood.

I’ve always felt that Americans and Australians have more in common than Americans and British. We both started out as British colonies, chafed in no small degree under the arrangement, had to tame the continents in which we grew, had massive frontiers in our “back yard,” and even struggle with unpleasant history vis-a-vis our indigenous people. We’re both much more heavily invested in Pacific affairs, and often wonder why we’re involved in European problems.