Barbarossa 1941 – USSR Invaded 75th Anniversary Series [Part Three]

July 4, 2016 by crew

Thanks for joining us again, Beasts of War, as we continue our commemorative wargaming explorations of Operation Barbarossa. Launched on June 22nd, 1941, this was the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, and the start of the bloodiest (and most important) theatre of World War II.

So far, we’ve seen the Germans launch the invasion in Part One, followed by some of the first desperate Soviet counterattacks. Part Two saw the colossal tank clash of at the Battle of Dubno and the Germans cross one of the huge rivers that are such an iconic feature of the Eurasian landscape.

But while all this was unfolding in the central and southern regions of Barbarossa, what was going on in the north?

Drive On Leningrad

July 16th, 1941

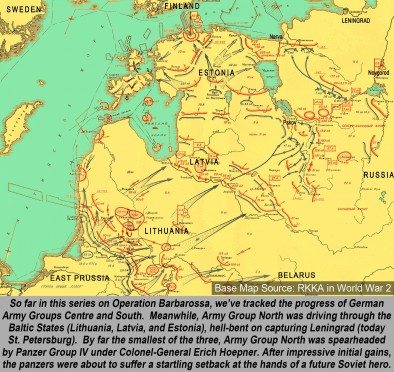

As mentioned previously, the Axis assault into the Soviet Union was organized into three immense “Army Groups,” North, South, and Centre. Army Group North was the smallest of the three, but still had in excess of 600,000 men, plus three panzer and two motorized divisions, organized into Panzer Group IV.

Army Group North’s immediate mission was to drive through Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia … then the northern heartland of Russia herself. Here they would cut the road and rail links between Moscow and Leningrad (today St. Petersburg), and finally take Leningrad itself.

As they did elsewhere along the Soviet frontier, the Germans achieved complete surprise and shoved deep into Soviet territory. In the Baltic States, much of the local population hated Stalin and were initially sympathetic to the German “liberators.” But resistance stiffened significantly once the Germans penetrated Russia proper.

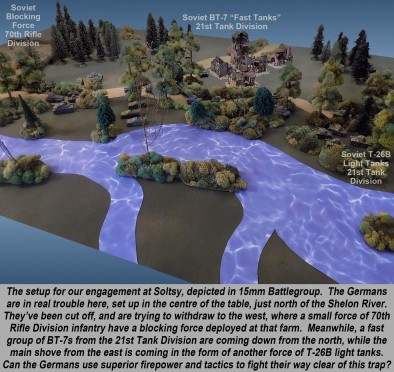

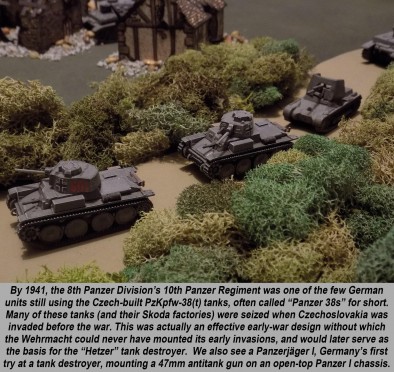

One of the first big setbacks came at the town of Soltsy, less than 200 kilometres south of Leningrad. On July 16th, the spearhead of the 8th Panzer Division found itself pinned against the Shelon River by a Soviet counterattack and nearly sliced off from the rest of the LVI Motorized Corps.

One of the great things about this battle are the characters involved. Commanding the LVI Motorized Corps is Erich von Manstein, widely regarded as one of the best operational commanders of World War II. His opponent was Nikolai Vatutin, one of the commanders of the recently-rebuilt Soviet 11th Army.

Vatutin was one of the better generals the Red Army would produce through the course of World War II. He and Manstein would meet time and time again, most notably commanding the biggest part of the Battle of Kursk in 1943. If Zhukov can be compared with Eisenhower, Vatutin can be compared with Montgomery or Bradley.

By mid-July, Army Group North had driven deep into the pine forests of northern Russia. Pivoting north toward Leningrad, they presented an “outside lane” on their open right flank that would be left dangerously exposed. While trying to protect this exposed flank, Manstein’s corps advanced too far, too fast, and became badly overextended.

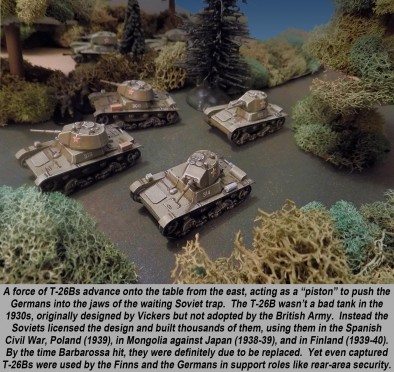

In particular, the forward elements of 8th Panzer Division had advanced too far ahead near the town of Soltsy. Seething and vengeful after horrific defeats, the Soviets hit the 8th Panzer with elements of the 70th Infantry and 21st Tank Divisions, trapping 8th Panzer against the Shelon River and hitting them from three sides.

For two days, most of the 8th Panzer fought for its life. They’d advanced out of range of their own artillery regiment and were utterly on their own. Manstein sent in the 3rd Motorized Division to rescue 8th Panzer, but soon they were beaten up almost as bad. At one point Manstein had to air-drop supplies to his panzers.

This was a fight 8th Panzer very nearly lost … and paid a dear, dear price to “win” (survive might be a better word). Meanwhile, they’d taken so much damage that LVI Corps would be unable to help the rest of Army Group North drive on Leningrad. Nikolai Vatutin had come within a whisker of winning a startling divisional-sized victory.

This was far from the last time Manstein and Vatutin would meet. Voronezh, Stalingrad, Kursk, and the Cherkassy Pocket … time and again these two would lock horns. But while Manstein would enjoy a post-war reputation as one of the finest commanders in World War II, Vatutin would be tragically killed by Ukrainian separatists in early 1944.

Storm in the North

August 22th, 1941

One thing about Barbarossa should always be remembered: how many willing allies Germany had. Barbarossa included forces from Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Italy, Slovakia, Croatia, Norway, France, Belgium, Spain, Austria, and Denmark. Even the Ukraine and yes . . . 600,000 soldiers from Russia herself . . . would eventually participate.

Another nation that participated in Barbarossa was Finland. Finnish participation was never wholehearted, however, and pursued to secure specific Finnish national interests rather than the ideological goose-stepping of Berlin. Besides, unlike Germany’s other allies, the Finns had a legitimate beef with the Soviet Union.

As many of you know, the Soviets invaded Finland in November, 1939. Despite a massive advantage in numbers, the Soviets were resolutely checked by the Finns in a brilliant winter campaign. Eventually the Finns were overcome, however, as the Soviets threw in still more forces. The Finns were forced to cede deep sections of territory in 1940.

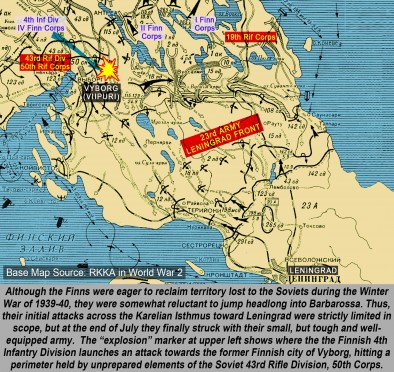

It was this territory the Finns wanted back when they agreed to participate in Barbarossa in 1941. Not trusting the Germans entirely, the Finns didn’t invade on June 22th. They waited until the spearheads of Army Group North drew close to Leningrad before finally opening their own offensive on July 31st, a full six weeks after Barbarossa started.

The Finns called this the “Continuation War” to stress its connection to Russia’s original invasion nineteen months previously. They certainly weren’t looking to further Berlin’s plans for “lebensraum” in the East. Accordingly, the Finns largely stopped their advance and dug in when they reached the old 1939 frontiers, well short of Leningrad.

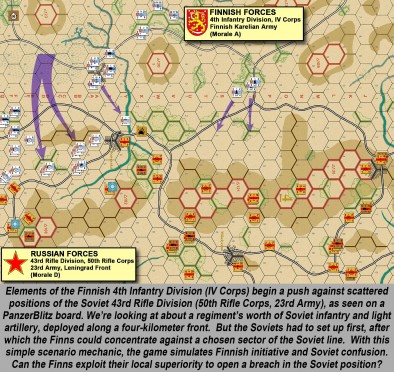

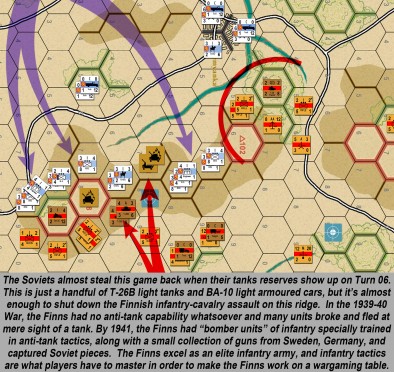

Still, the Soviet-Finnish front saw ferocious fighting in the late summer of 1941, especially in the Karelian Isthmus between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga. Here, the Finnish IV Corps advanced along the Gulf of Finland toward Vyborg (Viipuri), with the I and II Corps advancing along Lake Ladoga toward Käkisalmi.

Of course, Finland’s part in World War II was far from over. Cooperating with the German XXXVI Corps in the far north, they pushed into the Soviet Union, where the lines stabilized for almost three years. Finally, the Soviets hit back hard in the summer of 1944, and despite ferocious resistance, the Finns were again driven back.

Finally, Finland was forced to sue for a separate peace and again hand over all territories lost in the 1939-40 Winter War. In the end, the Finns wound up fighting AGAINST the Germans in the so-called Lapland War of 1944-45, when German divisions in the far north of Finland refused to withdraw into occupied Norway.

Battle for Kiev

August - September, 1941

Despite the incredible successes of June and July, by the middle of August the German High Command was starting to realize they’d underestimated the task before them. Yes, they were still driving into the Russian hinterland. Yes, they were still smashing huge Soviet armies. Yes, they were still winning. No, it still wasn’t enough.

The Soviet Union was just too big. No matter how deep the Germans pushed, there was always another river, another endless stretch of steppe. Diaries show how the sheer size of the country depressed German soldiers, as if they’d invaded another planet. The country was a void that swallowed the German army whole.

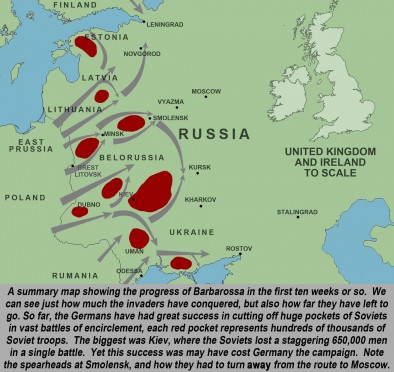

The gigantic scale of the campaign area allowed the Soviets to trade space for time … time to raise new armies. But by now Red Army losses had grown horrific even by Soviet standards. About three MILLION men had already been lost, mostly in gigantic “battles of encirclement.” The Soviets were running out of men, space, and time.

These battles of encirclement were something of a peculiar feature to the Eastern Front, partly because of the huge armies and wide-open steppe across which these manoeuvres were undertaken. Originally, the Germans employed encirclement to try and destroy the Red Army in place, before it could withdraw into the vast Soviet backcountry.

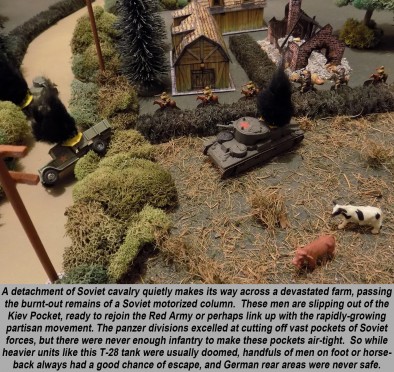

But the doctrine had flaws. For one, the infantry could never keep up with the panzers or motorized grenadiers. Second, there just weren’t enough infantry to “digest” these huge Soviet forces the panzers had “bitten off.” Many Soviets escaped the pockets or joined the partisans by the tens of thousands.

Hitler himself would soon intervene, insisting that more of these gigantic pockets had to be cut off, sealed, and annihilated. The biggest one would be at Kiev, where the remnants of the South-Western Front under General Kirponos (who’d launched the Battle of Dubno in Part Two) defiantly resisted in the capital of the Ukraine.

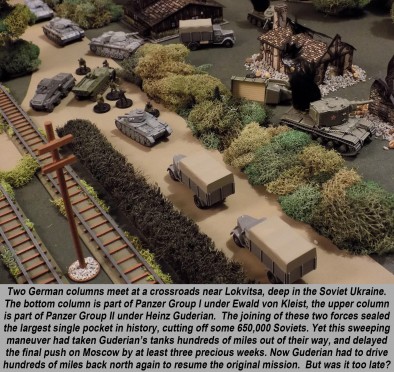

In the German centre, Guderian’s Panzer Group II had just sealed off another pocket with Hoth’s Panzer Group III at Smolensk. The road to Moscow was now more or less open. Fearful of his flanks and rear, however, Hitler ordered Guderian to abandon the drive on Moscow, and head south to help seal off the Soviets at Kiev.

Guderian was appalled, but his vociferous protests were overruled. Many consider this pivot on Kiev to be the single biggest operational-scale blunder of World War II. Granted, Guderian’s panzers linked up with those of Kleist’s Panzer Group I to seal off the Kiev Pocket, winning a momentous battle … but had they thrown away a war?

How big was the Kiev Pocket? The Soviets lost 650,000 troops, more than the US and Britain in all of World War II … combined. Kirponos himself was among the dead. Hitler called it the “greatest battle in history,” and if you judge by the number of casualties, Kiev really WAS the largest victory any army has ever won. Anywhere. Ever.

September was nearly over by the time Guderian’s panzers had redeployed back to the Moscow road. By then, the “rasputitsa” fall rains had drowned the countryside in an ocean of mud and the panzers were going nowhere. Kiev had been lost. But Moscow, and perhaps all of Russia … and perhaps all of World War II … had been saved.

Join us next week as Barbarossa finally runs out of steam. Not that the Germans are giving up, soon enough they will launch “Operation Typhoon,” their do-or-die push to finally destroy the Red Army and take Moscow. Just how close are the Germans going to come to absolute victory …

… and when will the Soviets finally strike back?

If you have an article that you’d like to write for Beasts Of War then you con get in contact with us at [email protected] to find out more!

"One of the great things about this battle are the characters involved. Commanding the LVI Motorized Corps is Erich von Manstein [...] His opponent was Nikolai Vatutin, one of the commanders of the recently-rebuilt Soviet 11th Army..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"About three MILLION men had already been lost, mostly in gigantic “battles of encirclement.” The Soviets were running out of men, space, and time..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

![Very Cool! Make Your Own Star Wars: Legion Imperial Agent & Officer | Review [7 Days Early Access]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2025/12/Star-Wars-Imperial-Agent-_-Officer-coverimage-V3-225-127.jpg)

Great read yet again

Thanks very much, @rasmus – We’ll be putting up a more detailed battle report for our Battlegroup game at Soltsy in the next couple of says. 😀

Yesterday, I played a game of Bolt Action inspired by the encirclement of Kiev. It was the 1st scenario of my 13th Guards Rifle Division Campaign which follows the 13th Guards throughout the war. It starts with the 87th Rifle Division, the division which would later be honored as Guards in Kiev.

Scenario 1

Escaping the Storm

Battle of Kiev, July 1, 1941

The 87th Rifle Division was defending the Ustiluga area of Kiev. The German panzer forces quickly cut off the division from the rest of the 5th Army. That was nearly a week ago. The city is surrounded by Axis invaders. It is only a matter of time before the Germans of the 2nd Panzer Group are reinforced to tighten the noose on the encircled Soviets. M.I. Blanka has decided it is now or never. He has ordered the men to break out the banners and bayonets. Today the 87th Rifles are rejoining 5th Army or die trying.

I don’t know how accurate the above is as it seems to occurred earlier than the actual battle. It sounds like my scenario was before the Soviets could even fight back and were just trying to regroup to mount a defense.

As for the game, it didn’t go well for the Soviets. All of their trucks they were using to escape with were immobilized by crack Axis machine gunners. The Red Army tried to use a smokescreen and a tributary of the Dneiper River to maintain separation from the German Panzers but were plagued by slowness of crossing moving water.

After a quick check, the Bolt Action background given above seems pretty accurate. I’ve found records of the 87th Rifle Division northwest of Kiev, engaged by Germans on July 1, and while other units seem to be retreating, the 87th does not.

Another map showing the 87th deployed northeast of the German advance on Zhitomir, west of Kiev, in the early part of July, 41.

Maps, models, and Panzerblitz. What’s not to love? Great job on all fronts, @oriskany .

I thought the Germans gave or sold the Finns some armour, and that they had a fair number of of ‘parked’ Soviet vehicles. I could be wrong. Or were they given the vehicles later?

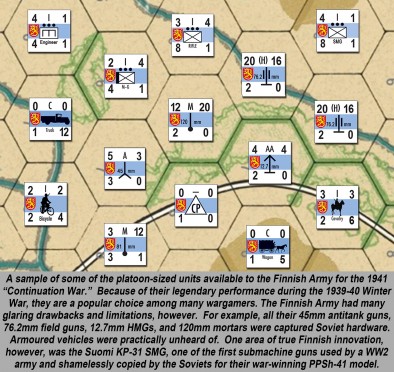

Thanks very much, @cpauls1 . Indeed the Germans would supply the Finns with some better armor, especially a unit of StuGs (a battalion’s worth, I think) later in the war. Until then I think the Finns had some captured tanks from the 39-40 Winter War, although these were in very small numbers.

The “parked” Soviet vehicles to which you refer (old tanks dug into the to ground as fixed emplacements if I’m reading you correctly) came into play when this part of the Eastern Front stabilized into a more “trench-model” war in 42 and 43, and of course when the Soviets shoved back into Finnish positions and forced them from the war in 1944.

Another great article. I love hearing about the different paths the army’s took. Again, I’m very glad to read about you doing all the work rather than have to do it myself 😉 I also LOVE the cows, cute touch.

Mooo. 😀

Those are some neat maps (as best as I can read them). If I get a chance to run this campaign again, I think I will try to model the table with what looks to be a railroad and, in fact, some rivers. It also looks like there is more vegetation that I originally thought if that is what those cloud-like shapes indicate. I was thinking outside of Kiev was more grass land, though; I don’t know why I would think that. I think I will start of thread of 13th Guards Rifle Division Bolt Action Campaign in the Historical Forum.

Awesome, @clash957 , I will definitely check out that thread. Those maps come from a great (if old) site, if the hyperlink below works just select “Maps” from the top menu. There are literally thousands of authentic war-era Soviet maps there. There’s even a reference document on there somewhere as an aid to translating Russian military abbreviations and acronyms (i.e., cd or CД = Rifle Division).

Damn, I forgot the link to the RKKA site:

http://www.armchairgeneral.com/rkkaww2/

Hope you find it useful for research! I sure do. 😀

Kiev might just have been the turning point of the war, rather than the later more famous battles

Very possible, @rasmus . If the Germans hadn’t spent the time turning down toward Kiev, they might have reached Moscow before running out of time and supplies. Then again, leaving the Red Army’s largest and most competently-led army group to the south, threatening an ever-lengthening and more exposed right wing. Always a great question and debate historians have haggled over for decades. 😀

If, and if ….

Blitzkrieg is all about momentum and Kiev is where some of that is lost in a great victory

Blitzkrieg is all about momentum and Kiev is where some of that is lost in a great victory

Certainly can’t argue with that, @rasmus . But did the German victory at Kiev cost them the 1941 campaign overall? It’s undeniably possible. But definite? Of course we’ll never know. The theory, however, has several “pros” and “cons” we can consider.

PRO: Historically, the Germans of Army Group Center missed taking Moscow by a mere couple of weeks at the most. If those weeks in September hadn’t been spent encircling Kiev (at least for Guderian’s Panzer Group II)?

CON: The Germans that would actually get closest to Moscow were in Panzer Group IV, not II. Panzer Group IV was currently involved in attempts to take Leningrad, not Kiev.

PRO: After the fall of Smolensk, the condition of the Soviet Western and Bryansk Fronts were deplorable. The Vyazma-Mozhaisk road to Moscow lay practically undefended. A solid punch up this highway by Panzer Groups III and II might have split the Soviets wide open BEFORE the autumn rains set in in October.

CON: The Battle of Kiev liquidated almost 700,000 troops and one of their best field commanders at the time, Mikhail Kirponos. How much of this power might have been redeployed in front of Moscow if the Germans hadn’t killed it in place at Kiev? They might have reached Moscow well enough, but never taken it.

PRO: Guderian’s Panzer Group II was run ragged making these marathon road trips, first hundreds of miles to the south to help Kleist’s Panzer Group I seal off Kiev, then hundreds of miles back north to take part in Operation Typhoon, at the center near Vyazma. Guderian’s panzer group would eventually disintegrate as much from overuse as from enemy action. If he’d been spared this massive diversion to the south?

CON: So Kiev is far to the west, and had effectively already been bypassed to the north (this forming to deep salient by which it was made such a tempting target in the first place). But if you push too far, too deep, on too narrow a front, there comes a point where you’re not so much behind the enemy than the enemy is behind you. Looking at the map, we can see how Army Group Center’s southern (right) wing becomes horrifically extended if they launch their encirclements on Vyazma, Mozhaisk, and beyond . . . without dealing with this massive force to the south. And it’s not like Army Group South or Kleist’s Panzer Group I could have handled Kirponos in Kiev by themselves . . .

And finally, would taking Moscow really have ended Soviet resistance like turning off a light switch? It definitely would have been a blow, a much bigger blow than is usually assumed by people who use Napoleon’s taking of Moscow in 1812 as an analogy. But immediately fatal? Who knows?

There are points in favor on both sides. 😀

What I did mean by “if and if …” no one know for sure, and your pro and cons give a more complete picture

Oh, absolutely, @rasmus . That was just my long-winded way of agreeing with you. 😀

I wonder … do cows count as mobile cover in Battlegroup ? 😉

It’s a neat little detail on a tabletop regardless.

Thanks, @limburger – they certainly gave some degree of cover for Corporal Upham in Saving Private Ryan . . . although of course those cows were considerably . . . less healthy. 🙁

Just a touch on the table, no game effect. (Unless @piers chimes in with a Battlegroup rule I don’t know about). 😀

great stuff @oriskany things may have worked out better if the Germans went for the (Zulu) formula with the horns of the bull.

supposedly (jolly deadly old boy)?

Indeed, @zorg , the “Double Envelopment” has had many names throughout different periods and cultures. The Zulus called it the Horns of the Bull, the Germans called it the “Kesselschlacht” (Cauldron battle) . . . I don’t know what Hannibal called it at Cannae but it might have been something like “Wow, so I guess that worked, didn’t it?” 😀

Of course it’s always different when applied on a tactical level (Carthaginians, Zulus), and on an operational level. One applies tactical pressure by collapsing and army in upon itself, the other logistical pressure by severing lines of retreat, supply, and communications.

Thanks, everyone, for keeping this thread going among. Always tough on a Themed Week. 😀

the down side is if the enemy got wise to the plan they could concentrate most of their army’s on taking out one of the horns.

Indeed, @zorg – double envelopment does require an initially dangerous division of force, which is why many battles rely on single envelopments (most of the Desert War battles, Bulge, the initial 1940 Blitzkrieg into France), etc.

Great work! Good thing you reminded me of the Lapland War, almost forgotten that one… Looking forward to the next part! 😀

Thanks very much, @neves1789 – of course we won’t be getting all the way to the 1944-45 Lapland War in this “Barbarossa” article series – but glad you like it and hope you like the next part, where we take a look at some of Germany’s other allies during this camapign (Hungarians and Vichy French) 😀

Ah excellent! I’m curious to learn more about Vichy French. After reading Alan Moorehead, I realised there was more politics to that state than at first glance!

Yeah, @neves1789 – it can be a touchy subject, and definitely complicated. During the Desert War, Vichy French and Free French went at it in full-scale, open combat in Syria. Kind of sad, actually, but it shows that both sides believed they were doing what was right for their country.

Then there’s the bloody nose the Vichy French gave to Patton (they never talk about that one very much) in NW Africa, the actions taken by the British (including the famous HMS Hood) against the French Navy at places like Toulon, Mers-al-Kebir, etc. Once the invasion of NW Africa got started, the supposed “failed” negotiations with Admiral Darlan and his abrupt assassination. People still “don’t know” who was behind that, it certainly wasn’t (*ahem*) British Intelligence that pulled that trigger . . .

Long story short, yes . . . there is a labyrinth of very complicated politics involved with this.

In regards to Barbarossa, we’ll be looking at the LVF (attached to Wehrmacht 7th Infantry Division at the time) and their participation in the Battle of Borodino (no, that’s not a typo . . . I’m talking about the 1941 Borodino, not 1812 Borodino) 😀

Ah yes the Vichy at Borodino, shame I forgot about that!

It’s indeed a touchy subject. The military museum in Les Invalides in Paris has one small wall panel dedicated to Vichy as opposed to an entire exhibit hall for the more traditional french history of WW2. Then again, so does the Belgian military museum in Brussels when it comes to collaboration…

In the meantime I’ve started reading Herman ‘Papa’ Hoth’s memoir on Barbarossa, mightily interesting! 😀

Indeed, @neves1789 – the “uncertain” regard with which many European countries have to regard this particular part of WW2 history is more than a little interesting. In their invasion of the Soviet Union, the Germans were assisted by French, Belgian, Danish, Norwegian, Finnish, Romanian, Bulgaria, Hungarian, Croatian, Austrian, Italian, and even Spanish troops. Eventually 600,000 Soviets would help. German occupational forces were heavily assisted by large portions of the local populace in places like Belarus, Ukraine, and especially the Baltic States of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. So that’s 15-17 nations that put soldiers into the field (one way or another) in at least tacit support of the Third Reich.

I think the simple truth is that in 1941, Germany looked like the “winning team” and frankly, Soviet Communism was scaring the hell out of a lot of people in Europe and beyond. The persistent dread of the “the hordes from the east” goes back to the Roman Empire.

Still, it’s understandable that these nations don’t feature such material heavily in their collective histories. Lord knows the United States and United Kingdom have plenty of chapters in their history they’d rather people forget.

Always meant to read Hoth’s memoirs. Definitely one of the underrated German generals, never a true genius like Manstein or a prima donna like Guderian and Rommel, but a guy who “just got shit done” in the vein of Kleist, Balck, and Henrici. Please let me know how it is when you get done! 😀

Definitely dont want to take anything from the minis and game tables, but I also like the bigger-scale maps that show the bigger picture. I know those take a long time to create, and i like the one showing the scale of UK by comparison.

Thanks, @gladesrunner . The source site for many of these maps (as put in the images themelves is “RKKA in World War II” – linked here: http://www.armchairgeneral.com/rkkaww2/

Of course I highlight small details that relate directly to the material under discussion, just for the sake of clarity.

One thing I like is that these images are sometimes chosen for the Backstager magazine upgrade elements or even front page panels, despite not being miniature “table shots.” @brennon and @lancorz really do a great job when putting these layouts together for the website. 😀

Hey I just realized…What no Leningrad? I know you are a good enough terrain maker you could have come up with a sweet Leningrad Model. I mean, it only took the ENTIRE BoW team to build 1/10th of Lloydoslavia. Surely you could have built the far less glorious Leningrad? 😉 Just kidding! I really do love how there is always something new in your map pics. The river isn’t new, but have it fill so much of the board is, same with the different way you laid out the train tracks.

Thanks, @gladesrunner – Yeah, that would be a fun project – build a perfect replica of the Hermitage Museum in 1/100 scale. No problem, I can knock that out on my lunchbreak at work today. 😀

love the museum with the figures outside @oriskany looks almost real? Lol

I’m tellin’ ya, man . . . that building took fore-e-e-e-ever to build on the table. 😀

time well spent.

Sure would have been

Did fighting during the siege get in the city it self ?

Great question, @rasmus , although the answer kind of depends by what you mean by “fighting.”

The Germans did get close enough to subject the city to a tremendous amount of first air attack, and then long-range artillery bombardment. So, yes, there were “military deaths” caused within the city and collateral damage. However, German ground troops never reached the city to my knowledge and stormed it “Stalingrad style.”

There was a tank factory in the city if I recall, and tanks would roll right off the assembly lines and to the front line units without even being painted (primer red or even just raw steel with weld burns still plainly visible). Might make for some interesting miniatures.

With the Finns coming down the Karelian Isthmus and the German 18th Army closing around the south, west, and even east, the city was soon totally sealed off. Many desperate attacks were mounted by the Soviets to break this choke hold. One of the worst was Operation Carnivore, which cost the Soviets an entire shock army in a disastrously botched counteroffensive.

Soon the Soviets were building a road over the ice of Lake Ladoga (practically an inland sea), called the “Road of Life.” It was treacherous and deadly, even when the ice was at its thickest. Men would drive the trucks standing on the running boards, so if their trucks fell through the ice they would at least have a chance. Many trucks took their drivers with them to the bottom of the lake. The ice was also under constant German air and artillery attack.

The siege would last 880 or so days, commonly referred to today as the “900 Days of Leningrad.”

The death tool in that first terrible winter of 1941-42 sounds like something out of an apocalypse novel. Hundreds of dead per hour. People playing cards, throwing dice, and drawing lots. If you lost the game they would hack off your leg so everyone else had something to eat.

One of the most haunting tales is the famous “Leningrad Metronome.” To keep the people’s hopes alive, the radio station played music constantly, 24 hours a day, Russian symphonies and operas, etc. When there was no music they simply played the tick-tick-tick of a piano metronome, just so the people had some sound, some sign of life. It was literally the heartbeat of the city.

Tick, tick, tick . . .

You’re still alive.

Tick, tick, tick . . .

We’re still coming for you.

Later winters were considerably easier. The Road of Life was bringing in some supplies, outgoing trucks had been bringing out people to ease the burden, and the city had taken advantage of the spring, summer, and fall or ’42 to start farming, gardening projects inside the city to grow some of their own food. But that first winter of 41-42 . . . Finally the German hold around the city was broken forever in February of 1944.

So was there any “combat” inside Leningrad? Technically, no. But there are still wartime cemeteries inside modern-day St. Petersburg, that hold 500,000 people . . .

. . . two of them. That makes at least 1 million people buried here, more than the US and UK lost in total military and civilian death in the entirety of World War II. That’s the dead from one Soviet city.

I did think so but I have not touched the eastern front in a meaningful way for a long while.

But a game of racing across the ice road, would be a interesting visual, and might leave a little bad taste in the mouth

I see what you mean, @rasmus , about a “Road of Life” game. Since the Germans mostly shelled it and bombed it, maybe there could be a way to create a SOLITAIRE game, where you start off with a force of Soviet trucks, escort units, aircraft, and counter-battery artillery pieces, and your job is to make sure as many trucks as possible make it across in x-amount of time.

That could also avoid the “bad taste” issue, since it’s a wargame that “saves lives” rather than “takes” them. After all, every truck you successfully get to its destination are more civilians that survive the siege. 😀

This was the most interesting article for me in the series @oriskany My knowledge of the northern part of the Eastern Front is really small, except some obvious facts so a big thank you for this. Waiting for the next installment. 🙂

Thanks, @yavasa . I agree that with the big battles of Dubno-Brody and Kiev in the south, and Brest-Litovsk, Vyazma, and Borodino / Mozhaisk in the center, the north is often the “poor relation” when it comes to big battles, war games, and general narrative. 😀

Yeah, I must agree, the most famous episode imho was the siege of Leningrad. Although a lot more was taking place on the Baltic Sea.

This is very true, @yavasa – Lots of smaller-scale naval action in the Baltic Sea, especially in 41, and even a series of small amphibious landings and invasions along the Baltic coast. Sadly, this was an aspect of the campaign I wasn’t able to include in the articles, and frankly haven’t read that much about myself.

Well @oriskany you cannot put too much into the articles. They are great reads because despite the amount of information you provide they are still clean and coherent reads. Plus these landings and naval engagements were as you say small and quite frankly no need to write about them while taking a closer look at the operational scale 🙂

Thanks, @yavasa . It’s just that the length of these articles (per BoW style guide) is supposed to be about 1000-1200 words and needless to say I blow that limit by a pretty wide margin. 😀 Hence the side threads in the forum, where we can really sink down into lower levels of detail. Plus, if other people have maps / photos / miniatures they want to show, they can upload pictures in the forum thread (unlike here in the front page).

I’m a bite late to these articles and I haven’t read the others yet. That’ll teach me to go on holiday. Anyway, thanks for all the time and effort you put into them @oriskany and all the effort you make answering people’s comments!

You’ve got me wondering about whether the Soviets lost the war by not pushing on to Moscow. I’ve never been struck by the idea that they would’ve won if they’d got to Moscow early on. Despite Stalin’s thoughts on not moving there’s no guarantee he’d have stuck around too long if the Germans were knocking at the door. It seemed to me that the movement of Soviet industry to the east and the ability to keep on making weapons probably had a bigger impact. No use having near limitless manpower if you can’t arm them. I do wonder sometimes if the options to do something else we love to chew over were ever realistic at the time.

I loved hearing about the Finns and all the allies the Nazis took with them. It does help to explain why the Germans were so confident about taking on Russia.

Thanks again.

Ok I just watched the intro video in the first part of this series and you went through the Moscow question there. I must make a point of starting from the beginning.

No worries, @ seldon9 – thanks for checking them out and for the great comment and questions. 😀

Yeah, the question of Moscow in 1941 has a lot of moving parts. Could the Germans have reached it in 1941? If they had, what real effect would it have had on the outcome of the campaign? Should the Germans have made their first big push toward Moscow, or should they have aimed southwards toward the economic / industrial prizes of the Ukraine, Donbas, and Caucasus? How close did the Germans even come to Moscow? Even this seemingly straightforward question has some gray area, as we’ll look at in Part 05.

Please understand, these are not rhetorical questions, but very real ones. All of them have at least some debatable content (even the last one about how close the Germans actually came … it depends on your definition of a “front line,” etc.). I certainly don’t claim to have any definitive answers on the “what if” scenarios posed above. There are plenty of valid arguments to be made from almost every angle, which is probably why people are still discussing them after 75 years. 😀

Army Group North certainly the Cinderella of the army groups. More and more units would be removed from it to make good losses of the other two. Units could not be removed completely from the line in fear of them being snapped up. Yet of all the army groups it can be argued that of all of them Army Group North actually came closest to achieving its initial objectives. Eventually they will even take its name from it, however long after the other 2 army groups have been consumed the men of Army Group North fought on.

After the war Manstein would go on to say that the huge strategic encirclements were in error and that the encirclements should have been done at the operational level. This would have kept the motorised and non-motorised formations closer together and the pockets could be properly emptied. However NATO and the U.S. post war believed the strategic encirclements were correct, so if the Russians and NATO had gone to war the same mistakes would have been made.

Good to see something about the Finns that was more than a passing reference. As Barbarossa opened the Luftwaffe used Finnish air bases to attack deep inside Russia as well as for refueling and re-arming. Stalin feared the Germans striking Russia via Finland and this was the reason for him invading Finland. Yet by invading Finland Stalin self created his own fear.

You say well equipped Finnish Army. Eclectic comes to my mind. They had hand-me-down equipment from most European country and Russia. The Finnish Army may well have been one of the best trained armies in Europe at the time. Life for most Finnish boys evolve joining the Civic Guard which is like a combination of the boy scouts, ethics club and the cadets. Military training was intense up to the age 17 when they transfer into the army 2 years conscription. Training in the Civic Guard included marksmanship, cross country skiing and even training on AA artillery. A point which is often overlooked is that Finnish middle level command was made up of highly experienced officers. Many had full training in German storm trooper tactics while the rest were fully trained by the Russian imperial army. They often polarised to these two schools of thought. Most units fought using both storm trooper and light infantry tactics. To be successful players using Finnish forces on the wargaming table need to be well versed in both.

During the Winter War the Finnish Army was not as good as it needed to be in logistics. Skis arriving without socks and the like. During the Winter War they had a limited number of German and Swedish made 37mm and there is an example of AT crews trained on German 37mm guns being issued the Swedish gun in the field.

Finland’s elite regular troops were the 3 cavalry regiment used for recon, even during winter, pursuit, exploitation and flank security. The Finns also had several types of special forces.

All up a great read and a visit back to familiar territory for me. Very much looking forward to the next installment of this series. 🙂

Thanks, @jamesevans140 –

Army Group North certainly the Cinderella of the army groups. More and more units would be removed from it to make good losses of the other two.

Couldn’t agree more. I think the biggest example of this was the transfer of PanzerGroup IV – two whole motorized (later panzer) corps plus all the group-level support units. At first, they sent Hoth’s Panzer Group III up to Leningrad while Guderian’s PzGp II was sent south to Kiev (so briefly AGN was actually reinforced), but all too quickly Army Group center took back PzGp III, and IV for good measure, for the last push on Moscow. These PzGrp IV troops would be the ones to actually get closest to Moscow, as we’ll see in Part 5. 😀

After the war Manstein would go on to say that the huge strategic encirclements were in error and that the encirclements should have been done at the operational level.

Certainly not going to argue against Manstein. 😀 I think a big part of the intended encirclements was to trap and destroy the vast bulk of the Red Army in place before it could withdraw into the Russian back country. Not sure if smaller, division- and corps-level encirclements would have allowed this. Still, given that the Red Army wasn’t withdrawing anyway thanks to Stalin’s “stand and die” orders, and the fact that the deeper encirclements could never be sealed air-tight, clearly the deeper encirclements didn’t work, either.

In the face of a plan that clearly did NOT work, it’s always interesting to consider alternatives.

Yet by invading Finland Stalin self created his own fear.

Couldn’t agree more. And didn’t the Soviets bomb Finland on June 22, 1941, more than a month before they officially joined the Eastern Front in what would become the “Continuation War?”

You say well equipped Finnish Army. Eclectic comes to my mind.

Actually, did I? I just “CNTL-F” searched the article and re-read the captions, where I talk about their collection of hand-me-down and captured antitank weapons and armor, then again in my reply to cpauls1’s question. In the screen capture showing all the Finnish PanzerBlitz counters, the number of counters doesn’t depict a large amount of weapons available to the Finns, but the fact that you need a large variety of counters because their equipment types had to be drawn from so many different sources. Eclectic, as you say. 😀

I only mention it because I know some very knowledgeable people read these articles and I try to be very careful about what I write. 😀

Long story short, yes, I agree with everything you say about the patched-together state of heavier Finnish weapons, especially the armor, antitank, and antiaircraft varieties.

Definitely glad, as always, you liked the article. Two more to go! 😀

You are quite right about the bombing of Finland @oriskany on the 22nd of June. This was a reprisal against Finland for allowing Luftwaffe bomber units to use Finnish airbase to refuel and re-use. Although Finnish units are not involved yet they were in it from the start by allowing German air units to attack out of Finland to reach deeper targets behind the northern frontier of Poland.

Finland was aware of Barbarossa long before many sections of the German armed forces. The German high command had to approach Finland in the early planning stages to get them to agree to allow the Luftwaffe to operate out of Finnish airbases. Then the Germans had the long job of transporting the large amount of bombs, ammunition, fuel, service equipment and spare parts. Then they had to start selecting servicing crews, barracks, offices and setup workshops. The list goes on. So a number of historians believe Finland had to be involved at an extremely early point in the planning so there was enough time to set these airbases up. How early is probably anyone’s guess but Finland had a permanent liaison officer attached to the German high command months before Barbarossa started. I have read accounts that states Finland took the opportunity to jump in and regain lost territory as Army Group North was approaching Leningrad however they miss the bombers flying out of Finland from the first day of the campaign and how much time and effort it took to establish the resources required to accomplish this.