Barbarossa 1941 – USSR Invaded 75th Anniversary Series [Part Five]

July 18, 2016 by crew

Well, Beasts of war, after five months of campaigning, 1.6 million square kilometres miles of conquered territory, and 6.8 million total casualties, we’re finally here. At last we come to the bloody conclusion of our commemorative article series on Germany’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union.

So far we’ve seen...

- Part One: The opening invasion and first Soviet counterattacks

- Part Two: The Battle of Dubno and the crossing of the Dniepr River

- Part Three: Operations in the north of Russia and the massive Battle of Kiev

- Part Four: Operation Typhoon and the last push toward Moscow

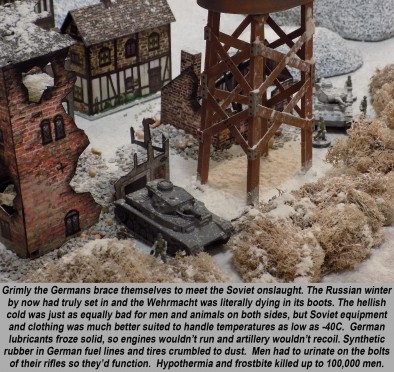

By late November, the Germans are exhausted, freezing, starving, and bled white. Some panzer divisions are down to five tanks. Yet some units are within artillery range of Red Square.

Others claim they can SEE the spires of the Kremlin through high-powered binoculars. Can the Germans mount that last decisive push? Or is it already too late?

Guderian Halted At Kashira

November, 1941

It’s a common misconception that the German advance toward Moscow (Operation Typhoon) was halted by the Russian winter. At least initially, the winter freezes were a godsend to German mechanized forces struggling toward the Kremlin. After all, freezing temperatures hardened the autumn mud … and once again the panzers were mobile.

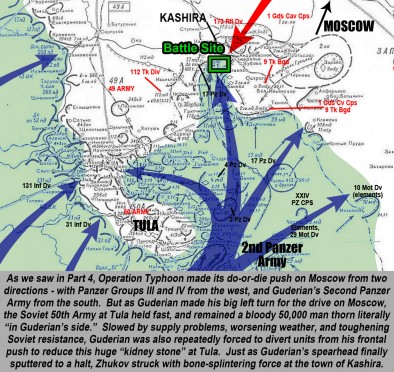

As we saw in part four, part of Operation Typhoon was mounted by General Guderian’s Second Panzer Army. Pushing past the city of Tula, Guderian turned to approach Moscow from the south. This put the Soviets in an operational dilemma, forcing them to choose which approach to Moscow they’d defend, and which they’d have to leave open.

There was just one problem. Tula didn’t fall. Rather than blitz through the city, Guderian was now grinding PAST it, losing momentum with every step. Finally, just when the Germans ran out of fuel, supplies, reserves, and endurance, the Soviets hit them with a shattering counterattack near the town of Kashira on November 27th.

Of course, the commander of Red Army forces in front of Moscow, the incomparable Georgi Zhukov, didn’t have much to work with. His reserves were extremely thin. Over six million Soviet troops had been killed, wounded, or captured since the outset of Barbarossa, and contrary to popular belief, Soviet manpower was not bottomless.

Scarce as they were, the bulk of Soviet reserves were being hoarded for a decisive showdown further north, where Panzer Groups III and IV had drawn much closer to Moscow. So to meet Guderian’s push from the south, Zhukov was beyond scraping the bottom of the barrel. He was digging into the ground on which the barrel sits.

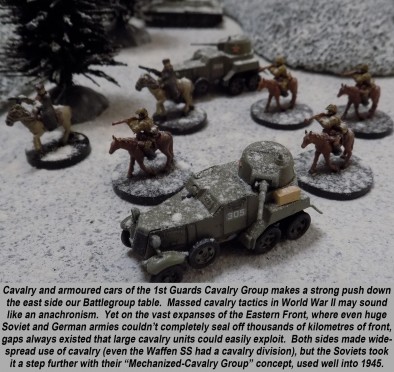

Accordingly, Zhukov cobbled together assorted artillery, engineer, and tank units … filling in the ranks with reserve, training, and even “penal” units. Together these were attached to Major-General P. A. Belov’s 2nd Cavalry Corps, earmarked for the desperate assault.

These units included half the 112th Tank Division, the 9th Tank Brigade, artillery and engineers detached from 173rd Rifle Division, a “Guards Mortar” regiment of Katyushas, and a scattering of smaller independent tank, militia, and training units. Together this patchwork force was rather euphemistically re-titled the “1st Guards Cavalry Corps.”

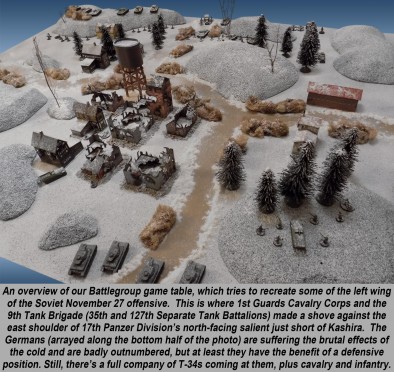

This “guards” title was practically a military eulogy delivered in advance, because the very NEXT day these men were hurled against the half-frozen remnants of the 17th Panzer Division (XXIV Panzer Corps) at Kashira. Zhukov’s exact orders to Belov were: “Restore the situation at any cost.”

The blow hit Guderian’s frazzled spearhead on November 27th. With the Germans so weak, the attack delivered a scorched, blood-splattered victory to the Soviets. Losses were still high, but the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps drove 17th Panzer back sixteen miles and forever closed the door on German hopes for taking Moscow from the south.

The counter-strike at Kashira did more than just smash the easternmost penetration by German forces in 1941. Despite what had seemed to be a crippling lack of equipment and reserves, the 1st Guards Cavalry Corps had won a clean victory for the Soviets, and did wonders for their morale.

The Red Army had also proven that tanks and cavalry (yes, CAVALRY) could work together on the Eastern Front with stunning effectiveness. Such “cavalry-mechanized groups” would score repeated successes against the Germans well into 1945. This was also one of the first documented uses of Red Army “tank rider” infantry.

Needless to say, XXIV Panzer Corps, and by extension the Second Panzer Army, was getting nowhere near Moscow. Guderian’s exhausted drive across the Russian steppe was decisively halted, never coming within ninety miles of the Soviet capital. Yet even now, the final outcome for the Battle of Moscow was being decided to the north.

Bridge at Khimki

December 2nd, 1941

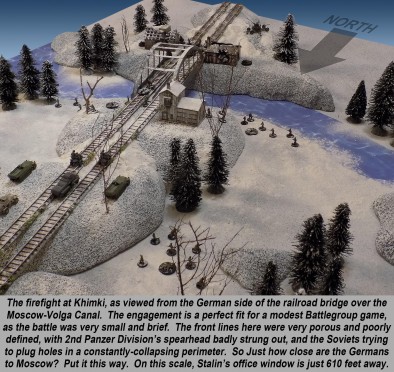

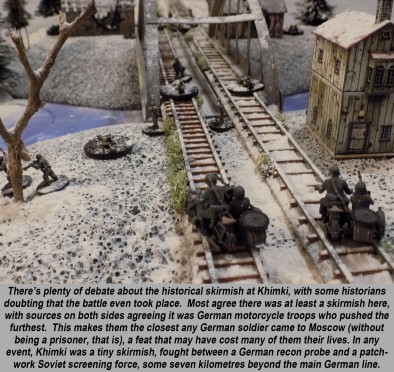

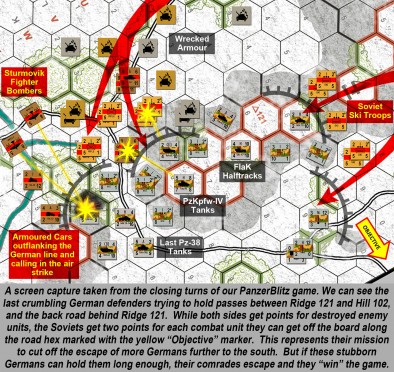

So just how close did the Germans really come to reaching Moscow? Well, the answer is predictably complex, but this is the question we explored with the next wargame in our series. We come to a bridge at a town called Khimki, less than 11.5 miles (18.5 km) from the very heart of Moscow.

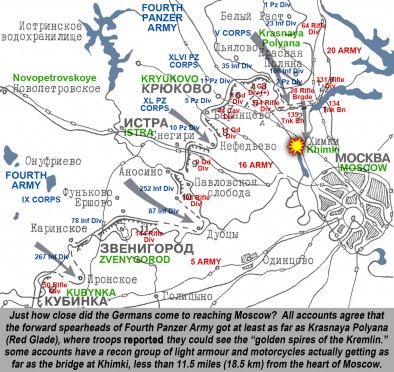

While Guderian was being repulsed to the south at places like Tula and Kashira, in the north the Germans had drawn much closer to Moscow. With the Fourth Army approaching from the west and Panzer Groups III and IV pushing down from the northwest, some of these spearheads got terrifying close to the Soviet capital.

The closest CONFIRMED location was held by 2nd Panzer Division, at a town called Krasnaya Polyana (Red Glade). From the church steeples, troops swore they could see the “golden spires” of the Kremlin through high-powered binoculars.

Okay, this report is a little suspect, since the Kremlin had been covered in camouflage netting against German air attack. But the fact remains that the Germans were very near to the Soviet capital. In fact, if 2nd Panzer had been equipped with the long-ranged, corps-level 17.0 cm artillery, they could have easily started shelling Red Square.

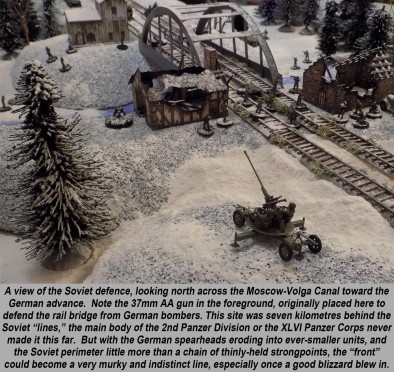

It’s quite possible, however, that some elements of 2nd Panzer got even closer. As the Soviet line stretched, bent, and buckled in an effort not to snap under German pressure, this part of the perimeter (almost ten kilometres long) was held only by an understrength Russian rifle brigade and a tank battalion. That’s extremely thin.

Under such conditions, it’s very easy to imagine German reconnaissance elements sneaking through and penetrating seven kilometres to a railroad bridge over the Moscow-Volga canal, which is exactly what many accounts say happened at Khimki on December 2nd, 1941.

Here, the German recon force (motorcycle infantry and maybe some halftracks and light armoured cars) ran into a Soviet screening force (28th Rifle Brigade, 135th Separate Tank Battalion, both part of Soviet 20th Army). Fire was exchanged, by all accounts the Germans got the worst of it, and the survivors withdrew.

To this day, a memorial stands on the spot recognized as the closest German forces ever came to Moscow. That said, Khimki doesn’t really represent the front line of a German panzer division, or the “official perimeter” of 2nd Panzer Division, the XLVI Panzer Corps, or Panzer Group IV.

No matter where one draws the line, what’s beyond debate is that the German advance had literally frozen in place. They’d covered a thousand kilometres and come within visual sight of Moscow. But they’d go no further. By the narrowest of possible margins, the largest military operation yet mounted in the history of warfare … had failed.

To put it simply, the Germans had pushed too hard, too long, too far. Still in summer uniforms, and without supplies or even adequate lubricants in their engines and artillery – Operation Typhoon fell apart, froze solid, and bled to death on the white Russian steppe. And if all this weren’t bad enough, the Soviets were finally ready to strike back.

Counterstrike!

December 5th, 1941

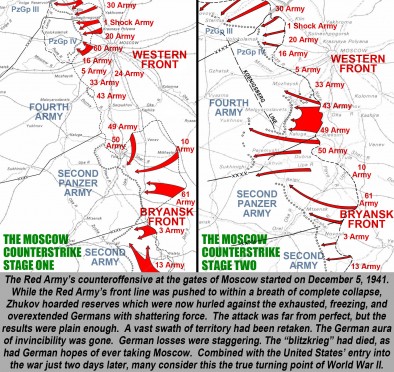

At last, the moment has come. Even as German spearheads belly-crawl within sight of Moscow, Georgi Zhukov has been carefully hoarding his reserves, including over thirty crack rifle divisions released from Siberia.

Grimly Zhukov has ignored pleas for help from the front, where Red Army units are splintering under remorseless German pressure. He is determined not to fritter away his reserves, but only release them when he has enough operational combat power to make a decisive difference.

Finally, on December 5th, Zhukov can wait no longer. His front line truly begins to disintegrate. Zhukov’s Moscow forces will never be stronger, the Germans will never be weaker. Only now does Zhukov finally release the storm gathered in his fist. The outcome of World War II changes upon this moment.

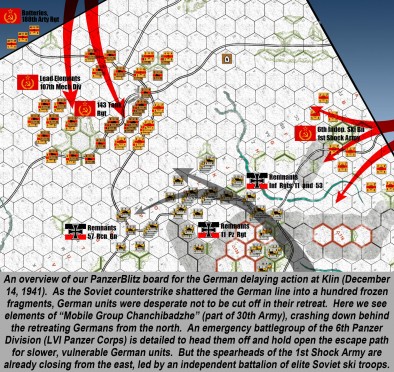

Overall, Zhukov’s plan is simple. In the centre, two armies will attack the German Fourth Army in front of Moscow and hold it in place. Six more armies will hit Guderian in the south, while seven MORE armies will hit Panzer Groups III and IV in the north, along with the German Ninth Army.

Once the Soviets break through on these wings, mechanized forces will rush through the gaps and converge at Vyazma, 150 kilometres behind the Germans, thus encircling all of Army Group Centre. Such is the plan, anyway. Whether the Red Army can conduct a manoeuvre of such operational depth remains to be seen.

Zhukov gives the order on the dark, misty, and snow-shrouded morning of Friday, December 5th, 1941. One after another, Soviet armies roll out a phased attack until the battlefield is in fiery, violent motion across 650 kilometres of front. That’s longer than England, the approximate distance between Hastings and Edinburgh.

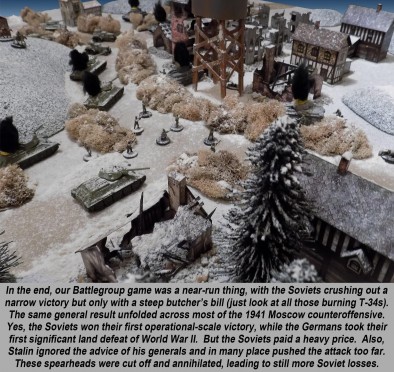

The Germans, quite simply, are shattered. Their last hopes are hung on the sad assumption that the Soviets have committed the very last of their reserves. They are freezing, starving, unable to move and sometimes even to fire. Struck with a blow of this magnitude, their lines crumble and evaporate.

German generals begin pulling back when and where they could, prompting the predictable screaming fits from Hitler. But too many generals simply have no choice. From hilltop to river to town, the Germans fall back to successive defensive strongpoints and fight with grim determination to hold back the immense Soviet tide.

Of course, this Soviet counterattack didn’t accomplish all its objectives. Although it lost tremendous casualties, equipment, and territory, Army Group Centre was not encircled. Still tactically superior, the Germans were able to parry, cut off, and annihilate some of these over-ambitious Soviet spearheads. This war was just getting started.

The Aftermath

In the end, the Moscow counter-offensive delivered for the Soviets what they needed most at the moment: survival. Moscow would NOT fall, the Red Army would NOT die, and the Soviets would survive unto 1942 and beyond. Hitler would fire no less than thirty generals over the debacle, including “Schnelle Heinz” Guderian.

The Germans, however, were going nowhere. Rhzev, Voronezh, Stalingrad, Khar’kov, Kursk, the Dniepr Bend, Leningrad, Cherkassy, Bagration, Berlin … countless more battles remained to be fought over the next three and a half years before final victory could be declared in what the Soviets would forever call “The Great Patriotic War.”

A Thank You!

I’d like to take this opportunity to thank @brennon and @lancorz for all the support they provide in publishing these articles, and @dignity and @johnlyons for the great interview when the series kicked off. And of course special thanks to @warzan for letting me ramble on so long about these historical topics on the site.

Most of all, I’d like to thank all of you, the supportive readers in the community who continue to welcome and support these article publications. Please add your comments below and keep the conversation going, and watch for a supporting forum thread with additional material and more detailed battle reports from the gaming table.

If you have an article that you’d like to write for Beasts Of War then you con get in contact with us at [email protected] to find out more!

"So just how close did the Germans really come to reaching Moscow? Well, the answer is predictably complex..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Moscow would NOT fall, the Red Army would NOT die, and the Soviets would survive unto 1942 and beyond..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

![Barbarossa 1941 – USSR Invaded 75th Anniversary Series [Part Five] Barbarossa 1941 – USSR Invaded 75th Anniversary Series [Part Five]](https://images.beastsofwar.com/2016/07/Barbossa-1941-Part-5-Cover-Image-394x221.jpg)

Surely this is just the end of part 1!

Another terrific article @oriskany and I never fail to enjoy the Germans finally getting a beating. The pieces I’d read about this in the past always focussed on Guderian leading the case and the charge for Moscow. I assumed it was him and his units that got closest. Zhukov’s legend just grows with every telling.

Thanks, @seldon9 – Indeed, you could write a whole “series of series” on the Eastern Front, whole libraries have been filled on the topic by writer far better than I. Part II could be the winter and spring of 1942, covering how the German Army was re-organized after the “purges” of 1941-42. There’s also the Demyansk Pocket, where a large German force was cut off for weeks and supplied by air until they could be relieved in a German counter-counter offensive. This was the example that convinced the Germans they could supply 6th Army in Stalingrad later. The Soviets have… Read more »

Phht. Lazy. Get ’em written 😉

A great series of articles

My back feels the sting of the lash. 😀 Bleeding fingers back on the keyboard . . .

sounds like a good plan so when is part two???

😀 @zorg – whenever John Lyons or Piers or @jamesevans140 sits down to write it. 😀

I think warren would have to un-cuff john lyons from the paint booth first for that one?

Great work again @oriskany very good addition to the University of Oriskany. Many Thanks.

Indeed, @m30wm1x – while Guderian is admittedly one of my favorite German generals of World War II, I freely confess he is sometimes “over-remembered” . . . much the same way guys like Montgomery, Rommel, and Patton are in the British, German, and American armies. His Panzer Leader post-war memoirs are, while a great source of information, also sauced-down with staggering quantities of “I told you so” and “if only they’d done as I’d said.” Kind of annoying. Casual histories of Operation Typhoon and the very last weeks in front of Moscow often record Guderian as “getting the furthest east”… Read more »

Modern History remember those who sell them self best – winners or loosers

Can’t argue with that. 😀

I guess we have to change “History is written by the winners” to “History is written by the Publicists”

I’ve always found, @rasmus , that “History is written by the victors” to be grossly oversimplified. History’s first draft is written by the winners (and the publicists). Then, usually after the first generation of people pass away or retire, comes the inevitable wave of “revisionists” who want to pick apart what happened, usually just to sell books, publish some half-ass thesis, or (worst of all), get some cartoon-ish History Channel documentary produced. Then come the counter-revisionists, the “no-nonsense professor” crowd, who push back against the “shock-historians” to set the record straight. Yawn. Like Philip Guedalla said: “History repeats itself. Historians… Read more »

Don’t get me started on H Channel – I can not get my self to call it history. For instance I like the show Vikings as a fantasy show which is taking ideas from history. But it is as factual as a modern Sherlock Homes show … (Just to take my “home” period in history) but the next generation might treat it as a factual show – that scares and saddens me.

I’m certainly no expert on the Viking period @rasmus . . . conversant, but nowhere near knowledgeable enough to “lead” a conversation. I think I know what you mean, though, where “dreams, visions,” and other supernatural elements are starting to take a bigger role in the show. I know we’re trying to see things from the characters’ perspectives (for whom such forces really were real) but I’m starting to worry the show’s producers and writers are overdoing it.

Another fantastic article @oriskany. I think I learn more about history from you than I ever did at school. Another thanks from me.

Thanks very much, @biggabum – always nice to hear!

Another absorbing read, so thank you.

Who takes the other side in all of the games played through the series? And PanzerBlitz looks like it could be easily turned into an online, Play by Email type game – has this been done?

Thanks, @redvers ~ As far as the other side in these games, it’s a mixed bag. The PanzerBlitz games were played a long time ago against my younger brother (BOW: @amphibiousmonster ). Miniatures games are sometimes played against BOW: gladesrunner, or a local friend in my old gaming group (the one I’m starting Battletech with now), or sometimes they are solitaire games. The truth is these articles have to be produced on a schedule, so sometimes I cant get an opponent ON TIME so wind up running the game with me on both sides. Of course “live play” is always… Read more »

It’s hard being objective when you’re playing against yourself – you always tend to favour one side for some reason. And younger siblings are always good for an easy win!

I might go and search out online hex based wargames – see if there is a ‘live’ version of Panzerblitz or an alternative game.

And never got into Battletech – I liked the clans and the universe but the mechs themselves were always so butt ugly.

Good points, @redvers – I knwo what you mean about trying to stay impartial in solitaire wargames. It’s basically impossible, which is why IO try to run live games whenever possible. It’s also vital for a system like Battlegroup, whose best features rely on a hidden total for your Battle Counter Rating system. That said, I can usually stay somewhat fair simply by always being on the side of the underdog. Whoever’s losing at the moment I usually find myself subconsciously “pulling for.” And hey, @amphibiousmonster has kicked my ass in plenty of games. 😀 I totally agree with you… Read more »

Wow! Best eye candy yet, @oriskany Beautiful winter terrain and models, and PB boards that always make me quiver (still waiting with baited breath for the Excel files 🙂 .

I noticed you had some Sturmoviks in the Soviet counterattack. I didn’t know they were out in ’41, nor did I think they had anything approaching parity in the air. Were they just tossed in for interest and balance?

Thanks, @cpauls1 – Crap, I didn’t send those files, did I? I promise I will send those today. Glad you liked the winter boards. Not sure if they would qualify as entries in the scatter terrain contest, I’ll have to get a solid footing on the actual rules of the contest and see what I can come up with. Yes, we had Sturmoviks in our game. Sturmovik ground attack planes were up and doing “well” a lot earlier than many people think. The IL-2 Sturmovik, MiG-3, and Pe-2 light bomber are kind of like the T-34 and KV-1 of the… Read more »

A great final installment @oriskany. A tremendous amount of detail and action beautifully summarized. You have taken us on a journey where we almost feel the German attack on Moscow fizzle out. For many years after the war historians almost edit out or at least play down the significance of the German defeat at the gates of Moscow. It would be argued that the battle of Britain, El Alamein, Stalingrad and other battles are the turning point of WW2. Yet it is here at the gates of Moscow that it is proved the Germans are not invincible, there war machine… Read more »

Thanks very much, @jamesevans140 – I agree that the battle of Moscow doesn’t get quite enough recognition as the one of the true turning points of World War 2, if not the turning point. A lot of turning points in history – Waterloo, Stalingrad, El Alamein, Gettysburg, the sack of Rome, are in fact the culminations of trends already in motion for a long while. The real turning points usually take place before the “casual” history books tend to say they did. Indeed, this “defensive battle” methodology that would make Zhukov both famous and infamous is played out here at… Read more »

Should get more “Old School Tactics” battles in soon – but I had to give up space in the first car for useless stuff like cloths. So it might take an other week or two

Priorities, priorities, @rasmus . 😀 Just kidding of course. Whenever it’s convenient, we hope to see some more battle reports. I’ll be rolling out some photos of the last battle for this series (Guderian Checked at Kashira) later tonight or early tomorrow morning. 😀

I where just getting a feel for the game – I can recommend it to any one who want a eastern front tactical hex and counters game with out a too steep learning curve

Tide of Iron: Fury of the Bear is another good one. 😀 Easy learning curve, great hex game, and even “2.5-D” miniatures / playing pieces.

https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/69962/tide-iron-fury-bear

oriskany

What a great set of articles, we both really enjoyed reading them and the pictures and maps really brings the words a life in your minds eye

Victoria and Chris

Thanks very much, @chrisg and @victoriag . 😀 Glad you liked the maps and tables, they’re admittedly the toughest part!

You know how much I love a battle report! The boards are amazing, as usual, and the pictures are awesome.

Another triumph. It’s all the ‘extra’ bits that bring it to life.

Thanks, @unclejimmy ! 😀 The more detailed battle reports are on the accompanying thread (there would never be enough space to put them in the actual articles)

http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/barbarossa-soviet-union-invaded-75-years-ago-today-battle-reports/

And not just battle reports, but Battlegroup battle reports, baby!

You’re a bad influence on the youth! Jamie just bought three books on Barbarossa, Bagration and Kursk. Cost over £50. I hope you are thoroughly disgusted with yourself.

Getting people interested in history and buying books indeed.

Battlegroup are the best rules for WW2 everyone. Makes FoW look like AoS by comparison!

Indeed, @unclejimmy – I hang my head in abject shame. 🙂 Elevating the level of discourse with my semi-educated yet aimless ramblings. Did Jamie enjoy those American Revolution books I think you said he bought a while ago? I have played very little FoW or FoW-esque (i.e., Team Yankee). and no AoS, so I can’t speak directly to the comparison, but I will agree that Battlegroup is one of the best WW2 games out there when it comes to miniature WW2 tactical gaming. Of course, I qualify that statement with “one of …” simply because I don’t profess to have… Read more »

As always great stuff, and thanks for nailing some of the common myths

Thanks very much, @rasmus ! 😀

A great reply @oriskany. I think the term ‘turning point’ is somewhat over used to emphasise what the author believes to be an important battle regardless of where the battle actually sits. Such as the siege of Tobruk it can be rightfully claimed by the defenders that they were the first to deliver a defeat to the Germans and not just once but twice. However you can’t call Tobruk a turning point as both defeats were at the tactical level and the victories did not lift the siege. The Russians at the battle of Moscow delivered a strategic defeat to… Read more »

Thanks, @jamesevans140 – The “defensive” or “counterattack” battle is indeed a stratagem that only works in very particular circumstances and carries very real risks. Is your higher command / government / populace going to put up with the horrific losses you will probably sustain in the first phase? Are you sure the enemy is going to hit you where you expect? As you mention, if the enemy sees you braced for a strike from a certain direction, they could well swing around and hit you from another vector. When you take the defense, you’re inherently giving the enemy the choice… Read more »

Those are some crazy good looking war pictures you have there.

Thanks, @clash957 – I like how the wargaming table photos came out , and then @lancorz puts what looks like a black and white filter over it to add that “authentic World War II” look. 😀 Another great job on the web page layout by Lance and Ben Shaw!

Thanks for the reply @oriskany. In a number of wargames you can feel the resolve of the plastic men wane. One of the best games for this is Games Workshop’s Lord of the Rings and you don’t feel it quite as much with Battlegroup as you are closer to the confusion of ground zero. I believe the defensive battle works better on the gaming table as politics and public moral rarely comes into it. Certainly when plastic men fall I don’t have to write a letter home to their mothers. The defensive battle works well for Zhukov as for him… Read more »

More great discussion, @jamesevans140 – I might have to take a moment and “disagree with myself” 😀 about defensive battles working well on tabletop games. On further thought, that might not always be the case. In Battlegroup, taking these kinds of losses can result in you drawing too many battle rating counters, which can lose you the game. So the attritional aspect may not always work in a wargame, I may have to walk that back a little. A game that rewards tactics and player-driven solutions like Battlegroup may not do so equally with “brute attrition.” Sill, a “defensive” or… Read more »

a great climax / end to the articles @oriskany

its not just oil the Germans would have had problems with diesel that starts to turn to jelly around -10/-15 even now in a cold winter the truckers can have that problem.

Awesome, thanks @zorg . So I wonder how the Soviets got around that problem, since their tanks ran on diesel while most German machines ran on gasoline (contrary to popular belief). Maybe some kind of additive (?) , because the Russian tanks were running great at temperatures way lower than that.

interesting, I don’t think they had a fuel shortage so the Russians may have just left the tank running more? or kept a fire going to heat the crew & the tank they may even have had a early pre-heat system similar to modern diesels?

that probably answers why German tanks were under powered then @oriskany

Fabulous work. One comedian remarked that if Napoleon or Hitler had played ‘Risk’ they would have known that taking on the vast expanse to the east was not a good idea

Thanks, @dorthonion – I think I remember that bit . . . Was that Eddie Izzard?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kpcxfsjIIbM

Always makes me laugh.

“Build up an empire and then celebrate by having a big world wa-a-a-a-ar . . . and losin’ the whole f***in’ empire by the end of the war . . .”

Excellent! Looking forward to the next article series on the Eastern Front! As the saying goes; Arbeit macht Frei 😉

Thanks, @neves1789 – but in all honesty I think “Frei macht Frei” – as in its time to take a break! 😀