Gaming The American War Of Independence Part Four – The War In The North

April 25, 2016 by crew

Rally to the colours, Beasts of War, as we continue our wargaming explorations of the American Revolution (presented by @oriskany and @chrisg). We’re examining some of the war’s most pivotal battles from both sides, as well as four distinct “echelon levels” of gaming … from the general’s table to the most intimate, visceral skirmish.

For those of you just joining us...

- Part One – The Shot Heard Round the World

- Part Two – Initial Battles & Campaigns

- Part Three – The Central Theatre

Now I know you you’re thinking. “Oh, look. Blue Continentals and British Redcoats in neat little lines.”

Not true, because this article explores a campaign with Hessians, six nations of Native Americans, and one of the bloodiest battles in American history with barely an Englishman within fifty miles. Simply put, this is the War in the North.

Background

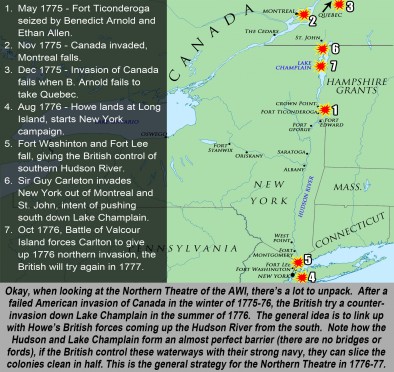

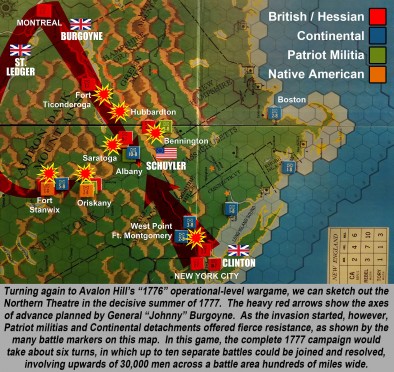

As we see in the above map, the Northern Theatre got underway barely a month after the Revolution started at Lexington and Concord. First, Benedict Arnold (yes, eventually the infamous traitor) and Ethan Allen surprised and captured Fort Ticonderoga, seizing the artillery that Washington would use to bluff the British out of Boston.

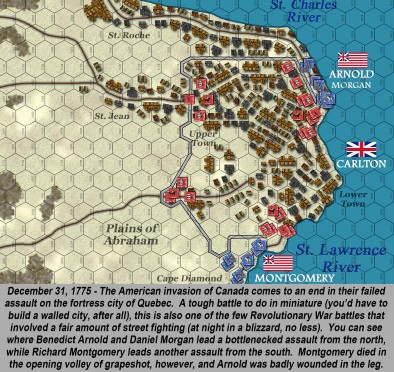

Next came an abortive American attempt to invade Canada and make it the “Fourteenth Colony.” Months of nightmarish starvation marches from two directions finally led to a failed assault and stalemated siege on Quebec. Again, Benedict Arnold was the key player here, despite suffering a terrible leg wound.

When this siege was broken, however, the Americans were driven away from Quebec and out of Montreal, back down into New York. By the summer of 1776, the British were ready to counter-invade down into New York.

The British invaded upper New York State in the summer of 1776. Their general plan was to take Lake Champlain, a deep mountain lake stretching 100 miles down through the virgin New York wilderness toward the headwaters of the Hudson River. Taking both the Hudson and Lake Champlain would basically cut the American colonies in half.

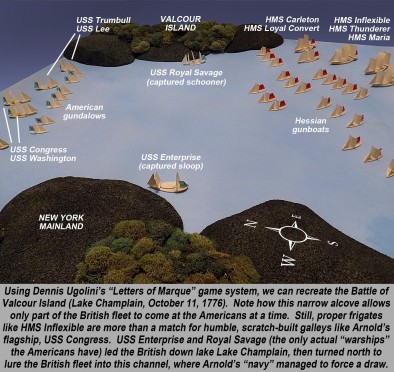

This precipitated one of the most curious naval battles in history, and one of the very few “fleet battles” of the Revolution. In preparation, the British sailed a flotilla up Canada’s St. Lawrence River, took it apart, carried the pieces overland, and reassembled their ships at the north tip of Lake Champlain.

Benedict Arnold, meanwhile, had to build his fleet the hard way. Vastly outclassed, the American “ships” managed to wedge themselves in a bottleneck near Valcour Island, and fight the British to a draw on Oct 11th, 1776. In the end, he’d have to burn his fleet to prevent capture, but Benedict Arnold had forestalled the British invasion for a year.

Northern Campaign - 1777

The British were fixated on their Champlain-Hudson invasion plan, and in 1777, a new general named “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne was determined to make it work. He’d take 9,000 British troops, Loyalists, Hessians, and Native American allies south down Lake Champlain and reach Albany, the capital of New York state.

Meanwhile, a supporting column (2,000 men) under General St. Ledger would swing west and drive along the Mohawk River, meeting Burgoyne in Albany. Most important of all, a heavy thrust from the main British army in New York would come north to complete the slicing off of New England from the rest of the colonies.

Things started off well for Burgoyne. His men called him “Gentleman Johnny” because he was unusually kind to them. He also liked to drink, gamble, write plays, and had with him on this campaign a mistress of legendary beauty. Some dismissed him as a playboy, but he was quick to show that he actually had a head on his shoulders for tactics.

When Burgoyne reached Fort Ticonderoga (the “Gibraltar or the North”), he managed to get cannon up on nearby Mount Defiance. The Americans had assumed the mountain was too steep. Just that fast, however, these guns were looking down right over the fort’s ramparts. Rendered instantly untenable, Ticonderoga had to be abandoned.

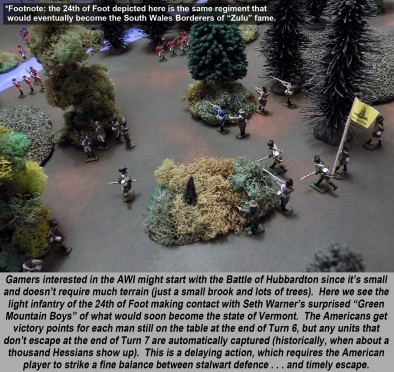

As the Americans retreated (without firing a shot), Burgoyne aggressively sent his advance guard after them. A desperate American rear guard was fought at the Battle of Hubbardton (July 7th, 1777), an easy British and Hessian victory that nevertheless took just enough time for most of the Ticonderoga garrison to escape.

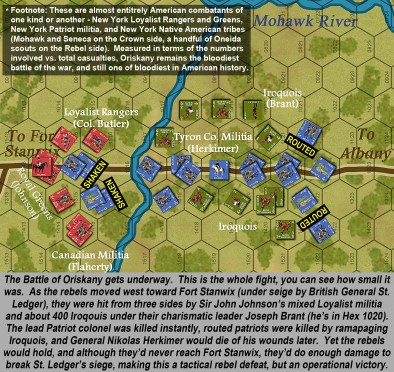

Other parts of the plan weren’t going so great. General St. Ledger’s support column (2,000 British troops, Loyalist militia, and Indians) that was supposed to be coming in from the west … was stalled at Fort Stanwix. The fort wouldn’t fall, and worse, a Patriot relief column was on its way, under a local commander named Nicholas Herkimer.

A mixed force of Loyalist militia and Iroquois ambushed this relief column of Patriot militia and pro-American natives at the Battle of Oriskany (August 6th, 1777). The two sides positively mauled each other, resulting in one of the bloodiest battles in American history (proportionate to numbers involved), not to mention an Iroquois civil war.

Even now, the Iroquois remember Oriskany as the “Place of Great Sadness.”

In the end, General St. Ledger would never take Fort Stanwix, eliminating one-third of Burgoyne’s three-pronged advance on Albany. Worse news soon came from New York City when General Clinton reported that with Howe’s main army chasing Washington near Philadelphia, he could not spare troops to advance on Albany from the south.

Just that fast, Burgoyne was on his own. He was also in the middle of nowhere. The patch of land between Lake Champlain and the Hudson River looks narrow on a map but in 1777 not a single road existed in this dense, hot, primordial forest. Burgoyne’s advance was soon reduced to a crawl, barely one mile per day.

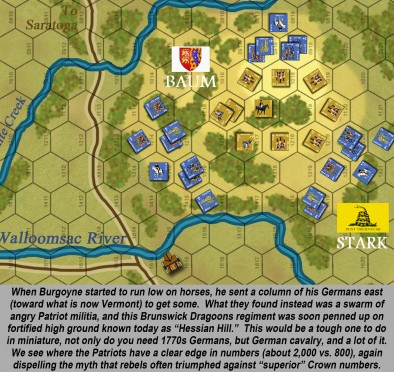

Supplies were soon running short, and the Native American allies were deserting. Even draft animals and horses started dying. When Burgoyne detached a force of Hessians to get more horses, they were met by ferocious Patriot militia at nearby Bennington (August 16th, 1777) and practically annihilated.

The Battle Of Saratoga

The Turning Point

Finally, Burgoyne’s exhausted army broke into more open country. By now, however, the Americans had massed a powerful army in his way, under the command of General Horatio Gates. His men hated him, calling him “Granny Gates” because of his British ways (he was formerly a major in the British Army) and his excessive caution.

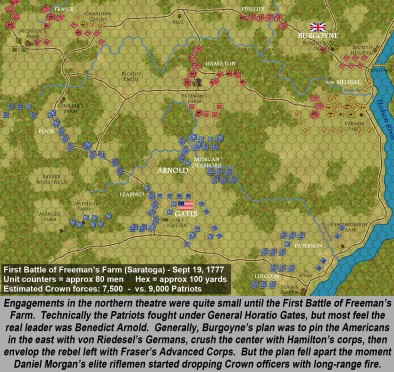

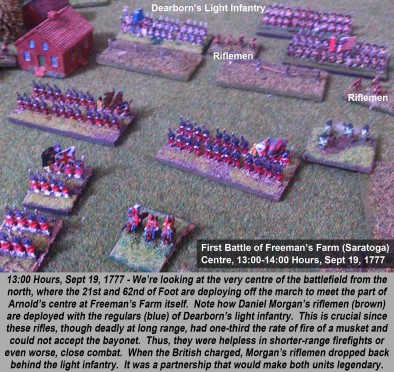

Subordinate to Gates was the American hero of the hour, Benedict Arnold. When Burgoyne tried to flank Gates’ position along the fortified high ground of Bemis Heights, he ran into Arnold’s force and started the First Battle of Freeman’s Farm (Sept 19th, 1777). Burgoyne failed, losing 600 men in the process.

Of course there would eventually be two battles at Freeman’s Farm, shortened in his history books to a single name synonymous with American victory, and a turning point in the whole Revolutionary War: Saratoga.

Burgoyne still hoped that Clinton might assist him with an attack from the south out of New York City. Movements were made and some battles fought, but never enough. Meanwhile, the deteriorating condition of Burgoyne’s army left him no option. The gambler gathered what strength he had left … and made one last throw of the dice.

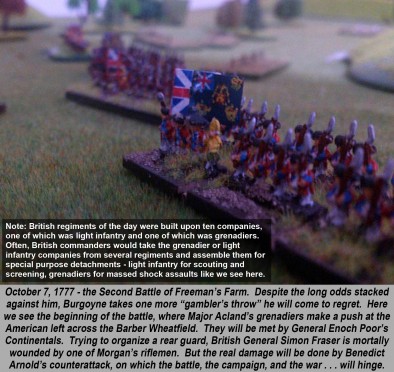

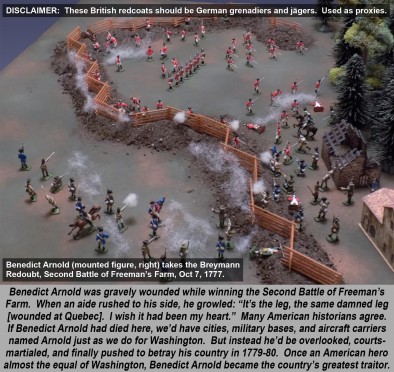

The Second Battle of Freeman’s Farm came on October 7th, 1777. Burgoyne’s attack was quickly halted, and his troops fell back to their fortified positions. That wasn’t the end of it, though. Benedict Arnold, despite having no actual command (he and Gates hated each other), basically “hijacked” the American army and led a counterattack.

The position that truly won the day stood on Burgoyne’s far right, the “Breymann Redoubt.” This was a fortified anchor of the Crown wing, held by Hessian troops under Lt. Colonel Breymann. In a historic charge, Arnold severed, flanked, and destroyed the position (suffering another terrible leg wound in the process).

With that redoubt gone, Burgoyne’s whole wing was left exposed. He’d also lost another 900 men, including Simon Frasier, one of his best generals. Outnumbered, outflanked, and soon to be starving, Burgoyne knew his invasion of New York had finally failed. The Battles of Saratoga were over. This war, and the world, would never be the same.

Finally, Burgoyne began a retreat. The Americans harassed his withdrawal, finally cutting off their retreat and forcing the surrender of 6,000 soldiers on October 17th (almost seven times as many as Washington had taken at Trenton). This was no detachment of Hessians, an entire British army had been wiped from the order of battle.

Of course, what made the American victories at Saratoga so important was the entry of France into the war, without which America could never have won this conflict. The diplomat Benjamin Franklin had been at the court of Louis XVI for over a year, but so far France refused to join until America “proved viable” with a major battlefield victory.

Saratoga proved to be that victory. With France in the war (and soon Spain and even the Netherlands after that), American victory finally became remotely possible, although still by no means certain. The war would now shift focus to the south, closer to Britain’s valuable assets in the Caribbean, as the conflict took on a global scope.

It was down here, in the American south, where the final historic chapter of this epic conflict would unfold. Add your comments, additions, and questions below … but above all come back next week for the final chapter in the amazing story that is the American War of Independence.

By James Johnson & Chris Goddard

If you would like to write for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"First, Benedict Arnold (yes, eventually the infamous traitor) and Ethan Allen surprised and captured Fort Ticonderoga, seizing the artillery that Washington would use to bluff the British out of Boston..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Meanwhile, the deteriorating condition of Burgoyne’s army left him no option. The gambler gathered what strength he had left and made one last throw of the dice..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

This is a really great set of articles. I was not very interested in the AWI period but suddenly I have found an interest and am painting up some 28mm Queens rangers, so thanks again Oriskanky and Chrisq.

Thanks very much, @hengest ! Hey, if we can get even a few gamers either playing the AWI or even interested in it, then all the work was worth it! 😀

Glad you like the series so far, be sure to tune in next week for the grand finale!

We also have additional conversation, material, and campaigns covered in our supporting thread, found here: http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/birth-of-the-united-states-wargaming-the-american-revolution/ . . . and help keep the conversation going on this great topic!

I love getting a chance to read about these “Lesser Known” battles, at least to the general public. I mean who now a days knows that the fledgling US tried to steal Canada…Ay?

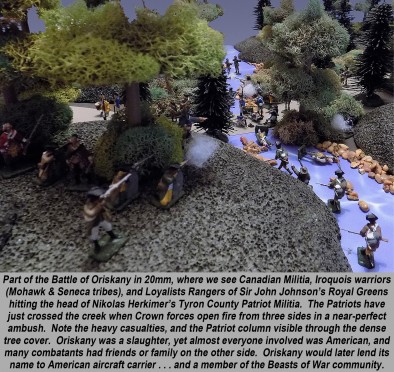

Also, that picture from the battle of Oriskany came out great! (I wonder why THAT battle got a mention and a cool photo..hmmmmm? 😉 Incuding Chris G’s 6mm guys also really give scope to the battles.

All in all a nice bit o’ writing!

Thanks, @gladesrunner . Indeed, the for Battle of Oriskany photo I really tired (successfully or not I suppose is up to the viewer) to get some depth of field. We’re looking over the shoulders of Canadian Militia and Johnson’s Royal Greens (note the Mohawk and Seneca guides there as well), shooting down into where the trail crosses this small tributary of the Mohawk River. Through the gaps ins the trees we can see the Patriot column in several places, and beyond that some more Loyalist militia crossing the stream to close the ambush’s far side. As far as whether the… Read more »

My haunts in the US and yet I only really noticed them over easter this year due to this series

Cheers guys

Yeah, @rasmus – I think Saratoga is now called Schuylerville (after Schuyler the overall American commander up there) – and nearby Saratoga Springs – more famous for old 20s mob parties and raising racehorses. Thanks for the comment as always! 😀

Excellent job! Can’t wait for the war to finally make its way to the south and to locales I recognize. 🙂

Thanks very much, @silverstars . We’ve got one more to go, where the Southern Theatre of the AWI is covered. Warm up the “Cornwallis Cannon Rule!” 😀

(Chris asked me to type this) Thank you everyone. We, Oriskany and Myself really enjoyed doing these article together, and i am please we have given everyone here a flavour of the time and history of the events that lead to the AWI and result in there independence

VictoriaG

(on behalf of ChrisG who is still not very well at present)

all my best to all

Victoria G pp chrisg

Thanks for checking in, @victoriag . Hoping @chrisg feels better and rejoins us soon. 😀

Small point on the 24th Foot becoming South Wales Borderers of ‘Zulu’ Fame on one of your images, mate, but at the time of the Zulu War they were still the 2nd Warwickshires and only became the South Wales Borderers after the Childers Reforms of 1881 (Zulu War is 1879). Sorry for being pedantic, mate. 😛 Love the articles, though. 😛

I blame the “Zulumovie, @crazyredcoat . 🙂 But yes, even a cursory check of Wikipedia confirms you are correct. Rourke’s Drift took place in 1879 – the reforms took place in 1881. Off by two years. 🙂

That’s what I get for wandering off of my chosen subject matter. 🙁 Thanks for the heads up and the comment! 😀

Benedict Arnold is perhaps the historical figure I am most interested in. I both admire and hate the man all while being a bit inspired by him. I say inspired because when I feel the world is being its most unfair and I want to give up, I think about Arnold’s betrayal and the fame and glory he could have had if he just stuck it out a while longer. Without a doubt West Point would have been Fort Arnold. I also think it would be entirely possible one of the states (and dozens of counties) would be named after… Read more »

I couldn’t have said it better myself, @clash957 . Seriously. I sat down in 2002-2003 and strangled out a novel manuscript based on Saratoga and basically the whole northern campaign (hence, Part 04 was definitely and admittedly my personal favorite of this article series). The story started with Ticonderoga, then Quebec, then Valcour Island, and finally Saratoga. Essentially, it was the story of a fictional character who “falls under the spell” of Benedict Arnold (he was ridiculously charismatic) who becomes something of a mentor father-figure for him. Anyway, I only mention that because through the year of research and writing,… Read more »

That’s exactly it. I wasn’t quite sure got the idea across about Arnold. On the novel/story idea, I too have considered writing an American Revolution piece of fiction. My idea is to follow the exploits and adventures of a man who joins the 1st Maryland Regiment weeks before the Battle of Long Island where his sergeant is among the Maryland 400 that didn’t make it back. A bit like Sean Bean’s Sharpe he is quickly promoted to sergeant when he shows a knack for logistics during Washington’s night time retreat. Being a fan of Robert E. Howard pulp stories, I… Read more »

Some great ideas, @clash957 . In reply: 1) If you’re interested to write / wargame / RPG in the American Revolution, a nearly-100% foolproof ironclad recommendation is Joseph Plumb Martin’s A Narrative of a Revolutionary Soldier: Some Adventures, Dangers, and Sufferings – As Written by Himself. This is only because (as you may have read in previous posts in previous threads, forgive me if I’m being repetitive here) his is the only complete autoboigraphy of a Revolutionary soldier. He started out as a private in the Continental Army at the age of 15 in 1776, he arrives “at the front”… Read more »

OMG, I remember that game! Amelia Weatherburn. My spoiled little Silver Fang werewolf, daughter of a Patriot shipping king. What a little princess, until you p***ed her off and she shifted to crinos-form on you and went to work with the claws and fangs! Man, I even had a name for her horse. What a great RPG chronicle, I always wished we finished it! 😀

Yep, @gladesrunner . I still have Jacob “Leather Paws” Barron’s character sheets filed away somewhere. 😀 Sept of Tomorrow’s Star! Liberty or Death!

Great bit of impromptu Benedict Arnold history @clash957 and @Oriskany ! I almost learn as much from the comments on your article as the article itself.

I also like how the article mentions other nations. Too often, especially on this side of the pond, we tend to only think of us “Yanks” and the “Brits” as being part of this war. When really the whole thing might have turned out differently if France and others hadn’t stepped in, either for our benefit or theirs.

Thanks, @gladesrunner . One more article to go! 😀

Another excellent article. Interesting from a gaming perspective, fascinating from an historical perspective. My history at school covered the period from the formation of the Earth to as far as the end of Queen Elizabeth 1. Given the Billions of years covered in that epoch, you would have thought that they could have covered the last 500 odd years as well. Sadly that was only for those that chose to take a qualification in history and opted for Geography instead. So I didn’t get to cover the English Civil War, let alone the AWI, but I do know a lot… Read more »

Thanks very much, @redvers . 😀 Should I admit that I had to look up what a “cuspate foreland” was? Once I saw the first picture, I said: “Oh those things.” 🙂 I should also admit that the English Civil War is another yawning black hole in my historical knowledge. I know the dates, I know Charles, I know Cromwell, I know Ireland, . . . and that’s about it. I just listed the “Oriskany encyclopedia” of ECW. 🙂 Anyway, glad we’re not laying the history on too thick. I’m trying to keep it focused on gaming, but there’s just… Read more »

I think your ECW encyclopedia is as extensive as mine.

The world’s biggest example of a Cuspate Foreland is in Kent, England. We’ve stuck the Dungeoness Nuclear Power Station on the end of it but inland is a small town called Rye. In medieval times it was a fishing village but now finds itself several miles inland. It’s a few miles down the coast from where William the Conqueror landed in 1066.

BoW – education and gaming at the same time. Can’t ask for more than that!

@redvers – “BoW – education and gaming at the same time. Can’t ask for more than that! Well, I suppose you could always ask for coffee and a pastry. Warren, see about getting the team on that, eh? 😀 On a serious note, I couldn’t agree more. Quick example: False modesty aside, I know a fair bit about the American Revolution. But when the first article hit, people were asking me (and telling me things) about the Penobscot Expedition in 1779 (It was in a novel by Bernard Cornwell of “Sharpe” fame). So in our side thread here (linked below),… Read more »

Now @oriskany and @chrisg a great read.

The battle of Oriskany as I can see from the terrain piece must have really been a bloody one. It really was a perfect ambush or at least it looks like it.

Indeed, @yavasa , the Crown forces picked their site well when setting up the ambush at Oriskany. Although with only one road, and thick woods all around, it’s tough not to pick a good ambush site. 🙂 Actually, it’s kind of tough to set up or portray on a gaming table just what that piece of ground was like. The road (narrow cow trail is probably a better term) runs east to west, along the shoulder of a valley with high ground to the south, sloping away down to the north, where the Mohawk River runs more or less parallel… Read more »

Thanks @oriskany 🙂

🙂

I picked up a British starter army at Salute last week. Hoping to have some Blackpowder games starting with Breeds Hill. I love the mix of colourful troops involved in this conflict which is so different to Napoleonics.

@denizen – great news! Are these 28mm from the Perry / Warlord Range? They seem to be the go-to AWI miniatures everyone is going for. Man, Breed’s Hill. You’re not messing around, are you? Jumping in with both feet! Great! I know what you mean about the colorful troops. Normally I am a WW2 / Moderns guy, where we are always discovering fascinating new shades of green, brown, beige, and gray. 🙂 Now the Patriots aren’t nearly as “blue” as movies make them out to be (especially in the early part of the war like Breed’s Hill), but the British… Read more »

Great series @oriskany, and timely enough the first episode of series 3 of Turn is on amazon prime today:-)

Awesome, @commodorerob – I’ve seen Season One, and Season Two is now on Netflix. Time for some binge watching this weekend! 😀 Hope all is well with you and you had fun at Salute.

@oriskany and @chrisg outstanding work, even if you have crushed my childhood innocence and what we were taught in school. 😉 I have always been partial to the “frontier” battles myself. Looking forward to the next chapter.

A 1,001 apologies, @stvitusdancern – not so much for “crushing” anything 🙂 but certainly for not having room in the articles for the Frontier Campaign. Vincennes, Fort Sackville, Kaskaskia, Cohokia, George Rogers Clarke, there is so much to cover out there. Sadly, casualties of the “editing room floor.” We’ve been these covering parts of the war that couldn’t be squeezed into the articles in our supporting forum thread, here: http://www.beastsofwar.com/groups/historical-games/forum/topic/birth-of-the-united-states-wargaming-the-american-revolution/ So far we’ve gamed through most of the Penobscot Expedition in Maine, which couldn’t be included in the article series but commanded quite a following among British subscribers because of… Read more »

Well done, gentlemen! You do a great job of putting your wargames into historical context. I have to admit, I’m not well versed on this war, but feel I have a fair grasp of the background and strategies since I’ve started reading your articles. Fascinating! I had never heard of the battles of Freeman’s farm! How do battles of that scope and size escape the history books? One of my favourite places in Canada is Kingston, Ontario. It is steeped in history, and many of the fortifications are still standing, and still being used by the military! I was billeted… Read more »

Thanks, @cpauls1 🙂 Actually the First and Second Battles of Freeman’s Farm are usually “historically condensed” into the Battle of Saratoga, a name which is much more widely known at least in American history books. Saratoga is usually the name most people know. We’ve had a pair of sloops, and old WW1 cruiser, the famous WW2 aircraft carrier, and the 1960s aircraft carrier named Saratoga Much more important than all that, however, the fictional aircraft carrier in the recent 2014 Godzilla movie was named USS Saratoga. So there. It was in a GODZILLA movie. Historical relevance cemented in place for… Read more »

It never fails, no matter how much you write about history, something cool is always missed. I guess that’s why historical gamers always have something new to game…or fight over…depending on the depth of the feelings. I also agree that BoW can double as history class…and a more entertaining one than most get in school… if you actually read all the articles. I can honestly say I know more about the Revolutionary War (Yes I said it, the Revolutionary War!) than I did before. Lastly…GODZILLA kicks that monkey ass! But I am glad the Saratoga didn’t get the Godzilla chomp… Read more »

indeed, as much as I love our Nimitz class aircraft carriers … even if they didn’t actually name one USS Saratoga … I don’t think USS Saratoga would have stood up to Godzilla. I mean, even if her strike group had full nuclear authority, as we saw in the movie even using nukes only pi**ed him off and made him stronger. +10 points for using the war’s correct name. 😀 Now how do you feel about building 1775 Quebec in 1/72 miniature, so we could do Benedict Arnold’s assault on Quebec proper justice? Do you think we could pile all… Read more »

Uhhhh tempting, but no. My desire for historical knowledge only goes so far.

🙂 Just kidding. Battles like that are what hexes, counters, and computers are for. 😀

Just to add a bit of gaming history to the affair. The first ever models produced by Grenadier were 25mm AWI figures

Wow, @torros … who hasn’t played with a Grenadier model or miniature at least once in their lives. These guys were the go-to for D&D miniatures since “Moses was in short pants.” 😀 I didn’t know about the AWI miniatures though. Sure enough, I looked it up, and you’re 100% right. They rolled out 25mm Revolution miniatures in 1976 as part of America’s Bicentennial. At least according to Wikipedia, the first miniature was a British grenadier, from which the company took its name. 😀

Great find! Thanks.

great stuff guys any chance of a wee extra story about benedict Arnold & why he turned? @oriskany

@zorg – A wee extra story on why Benedict Arnold turned? Man … that would probably be more than a “wee” story. Seriously, that is a complex, convoluted, and mysterious subject that I don’t think anyone knows the full answer two. If we could wave a magic wand and bring Benedict Arnold back for a beer and a chat I honestly don’t think even he could tell us. This is just one of those things that people do, one of those things that happen. I know his life didn’t turn out very well after the war, so I certainly wouldn’t… Read more »

Imagine that the government shafting the troops you would never hear that happening today? (aye right)

Well, at least we’ve come a long way from General MacArthur firing on American WW2 veterans in the streets of Washington DC for marching for their Veterans’ Benefits. 🙁

no they would use drones now?

Sad but true, @zorg . Sad but true.

Or an even more deadly weapon: Veteran’s Administration budget cutbacks and bureaucratic red tape. 🙁

the pen is mightier than the sword.

The series continues to provoke thought on the AWI at a great level of competence in just a short series, it has been great reading so many thanks @chrisg and @oriskany. I have considered the war in Canada a tactical defeat for the colonists but a strategic victory for tying down so many British troops and allies for so long preventing there use south of the boarder. I think the main loss here was the colonists attempting to create the 14th colony. How history might have been different is it was offered the French as a chance to reclaim their… Read more »

Wow, thanks once again @jamesevans140 . 😀 You pose some interesting ideas about the French “reclaiming lost possessions” in North America. While this certainly isn’t what happened in Canada, this sort of did happen in the modern US with respect to the Louisiana Territories vis-a-vis France, and the Florida territories with the Spanish. If memory serves (and it way well not), these traditionally French and Spanish territories were in fact British territories at the outset of the American Revolution – a little-known fact … okay, as in I didn’t know … when I started drawing some of the maps for… Read more »