Five Ancient Battles That Changed The World: Zama

November 10, 2014 by crew

Hannibal Barca is remembered by history as one of the great military commanders, and by the Romans as the man who almost destroyed them. His name became a byword for disaster in Rome, and as a bogeyman to threaten errant Roman children. His fate is intertwined with that of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, the first great Roman general. The two men met across the battlefield at the plain of Zama. At stake was the outcome of a war between the Roman Republic and Carthage, and the outcome would ultimately bring down both.

The Battle of Zama

Following a long series of conflicts, first against the tribes of central Italy, then against the Greeks of southern Italy, Rome had emerged as the dominant power on the peninsular by 270BC. The most powerful city in the western Mediterranean at this time was Carthage, situated on the coast of Tunisia. Between Carthage and Rome lay Sicily; and the two cities went to war for control of the island in 264. The First Punic War lasted 23 years and featured massive loss of life and expenditure of resources on both sides. The destruction of the Roman fleet in a storm is rivalled only by the destruction of the Mongol fleet in the kamikaze typhoon as the greatest single naval disaster in history (nothing else comes remotely close). A rebuilt fleet won a decisive naval engagement in 241 and with Carthage no longer able to supply its army on Sicily, it had no choice but to sue for peace.

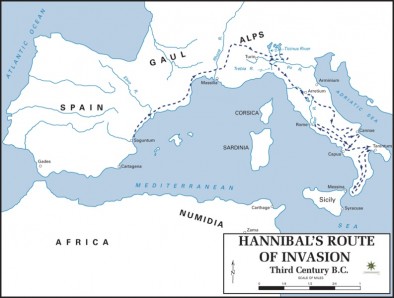

Stripped of control of Corsica, Sardinia, and parts of Africa, and financially exhausted by its indemnity payments to Rome, Carthage looked to Spain for an alternative source of revenue. The invasion was led by Hamilcar Barca, commander of the Sicilian army in the closing years of the war with Rome. By the time of his death in 228, Hamilcar had made significant territorial gains and secured control of numerous gold and silver mines.

He was briefly succeeded by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, who led the army until his own death in 221, and then by his son, Hannibal. At the time he took command, a generation had passed since the end of the First Punic War, and Rome had begun to cast envious glances at Carthaginian success in Spain. Using an attack by Hannibal on the city of Saguntum as a pretext, Rome declared war in 218. The Second Punic War had begun.

At this time, Rome had to yet to become an empire. Instead of a sole ruler, it shared power among its upper classes via a series of annual magistracies. The top jobs were the consuls, of which two were elected each year. Although they had political and religious duties, each consul was given command of half the Roman legions for the duration of their office. Traditionally, the consuls would campaign for one year, and then lay down their command to be taken over by the consuls of the following year.

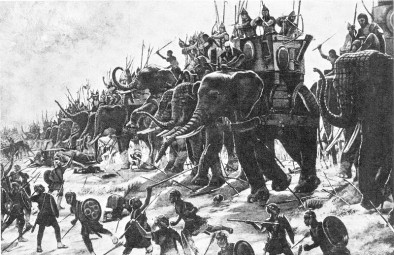

The consuls of 218 were Tiberius Sempronius Longus, and Publius Cornelius Scipio. Sempronius was sent with a fleet to Africa to raise supplies. Scipio, along with his brother Gnaeus, was sent to Spain to battle Hannibal. When Scipio put in at Massalia (now Marseille) to resupply, he was shocked to learn that Hannibal had marched his army out of Spain to take the fight to Rome. Hannibal’s harrowing crossing of the Alps with his army, elephants and all, is now legendary, and when he reached the other side, he replenished his forces by coming to terms with the Gallic tribes that occupied northern Italy. Scipio sent his brother on to Spain and set off to intercept Hannibal, but was defeated and badly wounded. Sempronius was recalled back to Italy and in December of 218, Hannibal crushed his army at Trebbia.

The following year, Scipio’s command in Spain was extended and he rejoined his brother there. Four new legions were raised to battle Hannibal in Italy, but in June of 217, Hannibal ambushed and destroyed the army of Gaius Flaminius at Lake Trasimene. In 216, Rome took the extraordinary step of fielding both consular armies together to try and defeat Hannibal. The resulting battle at Cannae proved to be Hannibal’s masterpiece. Despite being heavily outnumbered, Hannibal was able to encircle the Roman army. Cut off from any avenue of retreat, the resulting slaughter was so great that Cannae is possibly the bloodiest battle in history with as many as 70,000 Romans killed that day at the rate of 60 per second.

The victory left Rome on the verge of defeat, but Hannibal declined to press home his advantage by taking the city, most likely because his army didn’t have the capability to carry out a siege. Instead he took control of much of southern Italy and attempted to separate Rome from its allies. Rome in turn avoided pitched battles with Hannibal and focused on preventing him from capturing Roman allied cities, and preventing him from raising reinforcements. Meanwhile in Spain, the Scipio brothers had fought the Carthaginian army there to a stalemate, but in 211, both men died in battle.

Scipio’s son, also called Publius Cornelius Scipio (because that’s how the Roman aristocracy rolled), offered to take over command in Spain. At just 25 years old, Scipio was far too young to take a consular command, but with the war against Hannibal still raging in Italy, there was no-one else prepared to take over in Spain. Scipio arrived in 210, and by 206 he had driven the Carthaginian army from Spain. He returned to Rome to be elected consul for 205, still a decade younger than age limit for the post, and raised an army on Sicily to take the war to Carthage.

He landed in Africa in 204 and delivered and ambushed a joint Carthaginian/Numidian army. The Numidians were long-time allies of Carthage and their superb cavalry served in the Carthaginian army. Scipio was able to use the victory to place a new king on the Numidian throne and gain access to the cavalry himself. Surrounded by Scipio and cut-off from their allies, Carthage initially entered peace negotiations with him, but then abruptly withdrew and recalled Hannibal from Italy. In October of 202, they faced each other on the plain of Zama.

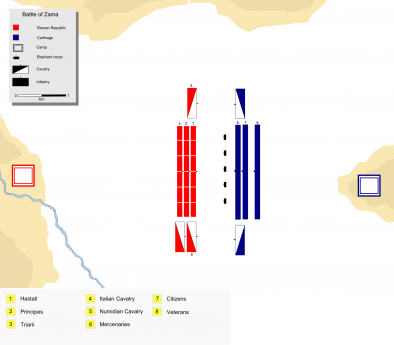

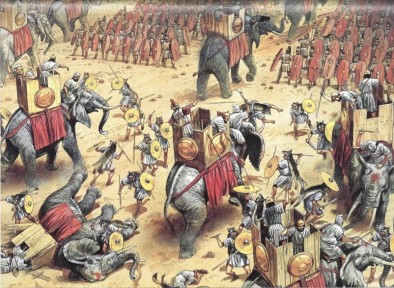

For once, Hannibal had the advantage in numbers. His army totalled 36,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and 80 elephants. Scipio’s army numbered 29,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry, but with Numidians serving on both sides, Hannibal no longer had an advantage in cavalry. Furthermore, his army consisted of the remnants of his Italian veterans boosted by hastily raised citizen-levy. Scipio’s army was well-trained and included the survivors of Cannae, who had been stationed on Sicily as punishment ever since.

Scipio also drew up his infantry in three lines. The stronger Numidian cavalry were placed to the right flank, and the weaker Italian cavalry to the left flank. Hannibal drew his infantry up into three lines, though he held his third line further back to prevent Scipio from encircling him with his superior cavalry. He stationed the elephants stationed in front of the infantry, the Numidian cavalry on the left facing Scipio’s, and the Carthaginian cavalry on the right.

The elephants provided Scipio with his most immediate problem. They had earlier been used to great effect against Rome by the Greek general, Pyrrhus, but were prone to panic and could only charge forward in straight lines. Scipio drilled his troops to open gaps in the line to allow an elephant charge to pass through, and ordered his cavalry on the flanks to blow their horns when the elephants came close. Several elephants were panicked by the horns and ploughed back into the Carthaginian left flank, the remainder were allowed to pass through the Roman line. Sensing their opportunity, the Numidian cavalry on the Roman right followed the rampaging elephants into the Carthaginian left.

With the elephants dealt with, Scipio brought the triarii up their usual position behind the first two lines and marched forward to engage the Carthaginian centre. The momentum swung back and forth in the centre before both Scipio and Hannibal pulled back and reformed their remaining troops into a single line. They once again engaged and this time fought to a bloody stalemate Hannibal had meanwhile had ordered his cavalry to retreat and pull the Roman cavalry away from the battlefield to prevent them attacking the sides of his line.

Once they were at a safe distance, the Carthaginian cavalry turned and engaged the Roman cavalry but were routed on both flanks. This allowed the Roman cavalry to return to the battle, approaching from behind the Carthaginian line. With Roman infantry in front of them and cavalry behind them, the Carthaginian line was surrounded and slaughtered. Carthage subsequently surrendered. The resulting treaty was so harsh it ended Carthage as a major force and Rome was left as the undisputed power in the western Mediterranean.

It’s difficult to know how a Carthaginian victory would have affected the outcome of the war. Rome had retaken Italy and taken control of Spain so defeat at Zama would at best have chased Rome out of Africa and prolonged the war. Had Scipio fallen, then Rome would have been deprived of the one general capable of going toe-to-toe with Hannibal. The likelihood is Rome would still have eventually won, albeit Carthage may not have been ruined in the process, and Rome would not have been able to so quickly turn its gaze east to the powerful Greek kingdoms of Alexander’s successors.

As much as Zama decided the Second Punic War, its effects went beyond simply paving the way for Rome’s control of the ancient Mediterranean. Faced with its greatest crisis, the Roman system had proved incapable of providing generals capable of meeting the threat of Hannibal. The annual turnover of consuls did not allow for generals to gain experience in the field, nor did it allow for keeping the best generals in the field. Hannibal had ruthlessly exploited this deficiency, and the system had to be abandoned to allow Scipio to emerge as a Rome’s first truly great military leader. The consequences would not be immediately felt, but ultimately, it would bring down the Roman Republic.

Gaming Zama

Zama is not a battle that is going to tax anyone’s supply of terrain. The plain was chosen for the battle precisely because it was so open and there is no indication in the sources that terrain proved a hindrance to either side. With both armies being roughly the same size and aligned directly opposite each other, Zama is a very easy battle to set-up. If your system has rules for commanders then both should be fielded in the centre at the rear, and both should be the best that your systems allows.

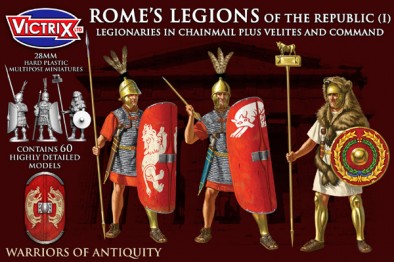

Scipio’s army was the classic manipular army of the Mid-Republic; arranged in three lines with the hastati in the front, princeps in the middle, and triarii at the rear. The Numidian cavalry are on the right, the Italian to the left, and there should be roughly twice as many Numidian as Italian. The infantry line would have been screened by skirmishers.

Hannibal also deployed his infantry in three lines. The exact make-up of the infantry is unclear though it seems likely that his most experienced troops would have been in the rear line, and the Carthaginian levy in the middle. His elephants were arrayed across the front of the infantry and skirmishers would likely have been in front of them. He had around two-thirds the amount of cavalry as Scipio, and this was evenly distributed to both flanks with Numidians on the left and Carthaginian on the right.

Overall, Hannibal will have around 80% of the infantry numbers of Scipio, and the Carthaginian levy in particular will likely be lower quality troops compared to Rome. There should be roughly one elephant per 350 infantry, though as all systems have to abstract numbers (assuming you don’t have a gaming table big enough to field around 80,000 minis), then you may have to adjust this to keep the list balanced.

Zama is a battle that could have gone very differently had the elephant charge been more effective, and you may find the battle hinges on it. The Romans should have rules allowing them to deal with the charge (such as the ones found in Warhammer Ancient Battles), else things may go badly for them.

The Series...

If you would like to write articles for Beasts of War then please contact me at [email protected] for more information!

"Despite being heavily outnumbered, Hannibal was able to encircle the Roman army..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"With both armies being roughly the same size and aligned directly opposite each other, Zama is a very easy battle to set-up..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Great stuff again – I know nothing about this battle aside from reference and it makes for an enlightening read! I particularly like that your exploration answers the question of ‘but why?’ – there is clear motivation for both sides, and concise history leading up to the confrontation. Am I making this a bromantic moment? er, lets see… yes, disappointed in… um…nothing really… oh! without your consistent use of the BC convention, I was *obviously* taken to believe that the battle spanned 6 centuries in length – it was natural for me to assume that many generations had risen, fought… Read more »

I would normally footnote an “all dates are BC(E)” but it didn’t seem like a good idea to have people scrolling down the screen and then back up again, especially for anyone reading it on their phone lol. I just left it at including it once at the start to try and establish it for the rest of the article.

It speaks to the quality of the art that I must grasp for such thin criticisms for my sarcasm.

I know it was said in jest but I actually think it’s a fair point and was worth addressing 🙂

It seems as if that could have done with an extra proof read. My apologies for the grammatical errors that crept in.

Doesn’t matter how many times you re-read your article draft, the second it goes up on screen you find something you missed. 🙂 Seriously, though, this is a fantastic piece of work. Since I’m not a medieval or fantasy guy, the only real “sword and spear” miniatures I’ve ever wanted to play have been ancients, but many times I balk at the sheer size of the engagements. Given the numbers involved at battles like Zama and Cannae, choosing the right system has got to be crucial . . . unless you want to rent a warehouse for your 80,000+ figures… Read more »

Good stuff Ben!

Mind you, always wondered as to whether the conquest of Spain would have been such a sure thing had the Romans lost at Zama, the Numantines and some of the other tribes were still a force to be reckoned with, and with Rome’s armies defeated in the sands of North Africa, who knows, the Numantines could have been the Iberian Peninsula’s Catuvellauni, taking advantage of the lull to reassert themselves once again… Or, could just be my imagination wondering off again haha

Good stuff! Hope you have another series in the pipeline 😉

It’s a fair point. Figuring out exactly what would have happened in a “what if” isn’t easy. A resurgent Carthage could have headed back to Spain under Hannibal’s leadership and reasserted their own control there, effectively returning things to the pre-war status quo. Given Rome’s relentless success during this period and their willingness to grind through adversity until they prevailed I do think that Carthage couldn’t reasonably have won the Punic wars. It didn’t have to turn out quite as bad as it did though.

to be honest, odds are even had Rome lost at Zama and the legions got their arses kicked in Spain, even if the Iberians had been able to make a go of it Rome probably would have just raised fresh troops within a couple of years and had another crack at it. Correct me if I’m wrong but didn’t that happen with Gracchus come to think of it? Was sent to head a column of reinforcements that got pretty badly beaten up, was forced to negotiate a peace only for the Senate to raise fresh troops and go back to… Read more »

Great article!

That was a interesting history lesson I only know the bones of the story nice to get some flesh on them very chaotic and bloody time.

Good article! But I’m more interested in the Mongols now. The poor sods must’ve felt quite shafted when their SECOND fleet goes under due to bad weather. I personally feel frustrated when by bus is late, so how do you feel when you just lost 4000 ships and all soldiers they carried? I guess snapping a pencil won’t suffice as stress relief in that case.

Why not write an article on the Mongol invasion Japan 🙂