Five Ancient Battles That Changed The World: Chaeronea

November 3, 2014 by crew

The repulsion of Xerxes’ invasion of Greece in 479BC ushered in a golden age for the Greek city-states. Athens and Sparta contended for domination for much of the fifth century, ultimately fighting a protracted war which culminated in the surrender of Athens in 404. Sparta then enjoyed several decades of uncontested dominance, but its hegemony hid a slow decline which was brutally exposed in 371 by the brilliant Theban general, Epaminondas. He again defeated a Spartan army in 362, but his death in the battle brought an end to a decade of Theban dominance in Greece.

The Battle Of Chaeronea

Situated in the north-east Aegean, the kingdom of Macedon had been a decidedly minor player in Greek affairs throughout this period. Macedon was seen by the Greeks to the south as a backward country of uncouth tribesmen, and it was ruled by a monarchy characterised by intrigue and infighting. The period of Theban dominance had been a particularly tumultuous time for the Macedonian monarchy, and as security for its good behaviour, the youngest brother of the ruling dynasty was taken hostage by Thebes in 368. Philip was just fourteen when he arrived in Thebes, eighteen when he left, and by the age of 23 had himself become king of Macedon when he was appointed regent to his six year-old nephew following the death of his brother in an ill-fated attempt to invade Illyria.

Philip wasted no time in securing the throne for himself, but he had inherited a precarious position. The Macedonian army had been severely weakened in Illyria, and Athens retained a strong interest in recovering access to gold mines in regions they had once controlled. Capturing control of the mines for himself, Philip used the wealth to institute a large, professional army, which he used to unify the various peoples who made up his kingdom.

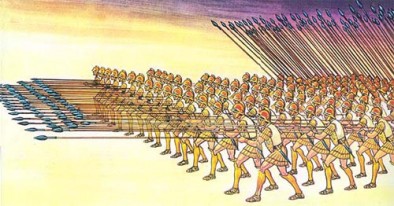

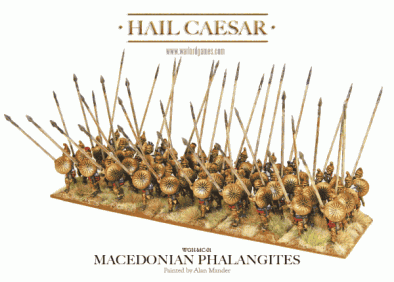

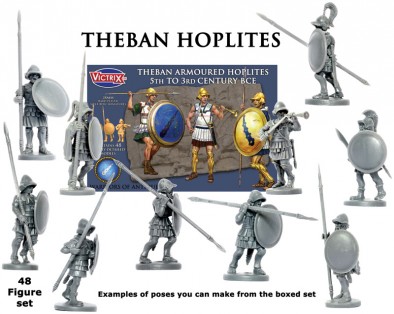

Traditional hoplite warfare involved the meeting of two shallow lines of roughly equal width. The hoplite was armed with large shield and a two-metre long spear. Fielded closely together, the hoplite phalanx presented a strong shieldwall that was difficult to penetrate. The long spears then created a zone in front of the line into which several ranks of hoplites could attack at once. Drawing upon the military education he had received at Thebes, Philip fielded his troops in a deeper formation designed to attack the enemy line at a weak point. He replaced the spear with the five-metre long sarissa, which meant doing away with the shieldwall but allowed for many more ranks to attack an even deeper space in front of the line.

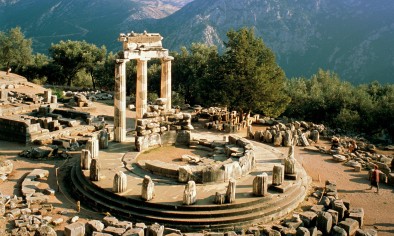

As Philip was consolidating his position, the Third Sacred War broke out in central Greece in 356. At the instigation of Thebes, the Amphictyonic League, which controlled the sacred site of Delphi, imposed a large fine on Thebes’ rival, Phocis. The fine was so big that Phocis could not pay. The Phocians responded by seizing the treasures from the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, and used the money to field a large mercenary army against the league and its allies. Philip was drawn into the protracted conflict in 353 and suffered two defeats at the hands of the Phocians. A year later, he returned with a larger army and won a crushing victory.

For the next six years, Philip stayed out of the war and extended his dominance of northern Greece. When he returned in 346, his armies were so powerful the Phocians surrendered rather than face them. The end of the war placed Athens in a difficult position and they too were forced to make peace with Philip. In just thirteen years, Philip had turned Macedon into the most powerful region of Greece.

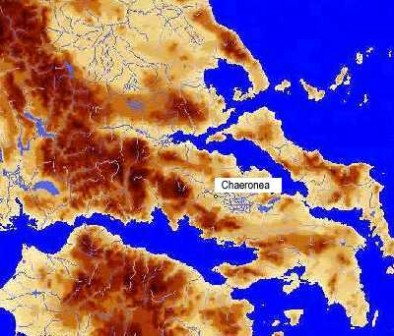

The peace with Philip didn’t sit well with many in Athens and by the end of the decade they were openly flouting it. The final straw for Philip came in 339 when he was besieging the cities of Byzantium and Perinthus. The Athenians formed an alliance with Byzantium which hindered Philip’s ability to capture the city and weakened his standing in Greece. Philip decided to march south to deal with Athens once and for all. The Athenians responded by forming an alliance with Thebes. Many other Greek city-states joined them in the cause of freeing Greece from Macedonian hegemony. In August of 338, Philip marched his army directly towards to the allied Greek army, and they met near the city of Chaeronea with the fate of the Greeks on the line.

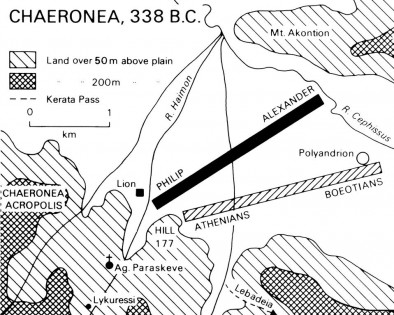

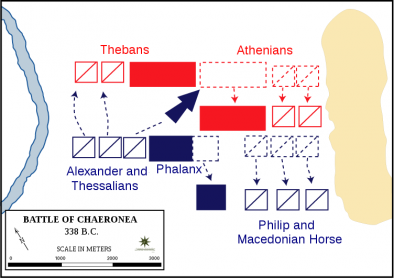

The Greek army took a strong defensive position with its left flank occupying higher ground in foothills, and its right anchored against a river. The Athenians anchored the left, the Thebans the right, with the allies in between. The Thebans fielded the Sacred Band, an elite unit of three hundred hoplites who were considered the finest warriors in Greece at the time. The line was arrayed obliquely with the left flank presented closer towards the Macedonian army. This presented Philip with a problem. If he chose to concentrate on that flank then he was fighting uphill, but if he attacked the right flank he was exposing the side of his line. Philip took command of the Macedonian right and placed his 18 year old son, Alexander, in command of the left.

We are not blessed with reliable accounts of the battle itself, but from what we have it appears that Philip initially engaged the Athenians on the Greek left, but then withdrew. The Athenians took the bait and followed, abandoning their superior position and overextending their line. Philip routed them and at the same time, Alexander routed the Greek right. Casualties were low as is usual for hoplite battles; Athens and Thebes each lost approximately one thousand hoplites, but the Sacred Band was wiped out almost to a man.

The victory at Chaeronea ended the era of the independent Greek city-states and left Philip firmly in control of Greece. The Athenians braced themselves for a siege but Philip had bigger fish to fry. For most of the fourth century, the Greeks believed that the Persian Empire was weak and ready to fall. Rather than pressing his claim to rule the Greeks, he placed himself at the head of a federation of Greek city-states with the intention of conquering Persia. Before he could do so, he was assassinated, and the glory fell to Alexander. Had the allied Greek army held firm at Chaeronea, then Alexander may well have been a footnote in history, and the great Hellenistic kingdoms which gave way to the Roman Empire may never have arisen.

Wargaming Chaeronea

Chaeronea offers the wargamer the chance to field a veritable Who’s Who of ancient Greek warfare. It pits the hoplite phalanx against the Macedonian phalanx, puts Philip and Alexander on the field together, and features the clash of the Theban Sacred Band against the Macedonian companions. Alexander’s companions were an elite cavalry force that served as his main shock troops. It should be pointed out, though, that at Chaeronea, the companions are not mentioned as being mounted so it may be anachronistic to field them in the manner they were fielded in the conquest of Persia, but if you want to do it, knock yourself out!

One of my main criteria when selecting a battle for this series is that both sides could reasonably have been victorious. The Macedonian phalanx is considered so superior to its hoplite cousin that Philip’s victory may seem like a foregone conclusion. If the sources are to be believed, however, then the battle was a fierce one that lasted all day. The key to the Greek resistance will likely have been their strong defensive position so it is imperative that this translate to the gaming table, else most systems will offer the Macedonians an easy victory. The Greeks also did not need to engage Philip. He was the one who needed to defeat them so the Macedonian player cannot be allowed not to cross the battlefield and engage them.

As usual with Greek battles, we hear little about light troops and cavalry. The best estimates put the Macedonian army at 30,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. We’re told the Greek army was bigger, though not by how much. It probably had little in the way of effective cavalry so I advise adding between 10-25% more infantry than the amount of Macedonian infantry that is fielded. Both sides would have some light infantry screening their lines, and there was probably some light cavalry on the flanks. The battle could degenerate into a grind, in which the two lines meet and fight in melee until one side breaks. To simulate Philip’s tactics, it may be worth adding rules which allow him to feign retreat to bring the Greek’s out of their position.

Read part one of this series:- The Battle of Marathon

If you would like to write articles for Beasts of War then please contact me at [email protected] for more information!

"Fielded closely together, the hoplite phalanx presented a strong shieldwall that was difficult to penetrate..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Chaeronea offers the wargamer the chance to field a veritable Who’s Who of ancient Greek warfare..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Great write-up once again Ben, really great detail and just the right blend of history and wargamming (that is to say, heavy on the history and commentary). This would be an epic battle to simulate – and I do like that you chose it based on the fact that if could have gone to either force. Good stuff! As always, I will forego a completely positive response (lest I be accused of a man-crush) and say, I don’t particularly like the photo you chose for the Temple of Athena at Delphi, it could have used better lighting! Other than that,… Read more »

I shall try harder next time lol

Great article, and of course the Victrix miniatures always makes me drool lol.

The shieldwall didn’t disappear entirely, as one of the illustrations suggests. The Macedonians adopted a smaller shield, similar to the pelta (the name escapes me right now), which looped around the arm and the neck, thus transferring the weight of the heavy sarissa from the left arm to the back. This smaller shield also allowed for a tighter phalanx formation, and therefore ensured even more weapons on a frontage than a hoplite formation could bring to bear.

That particular illustration following the paragraph in which I said Philip abandoned the hoplite shieldwalll may be a little misleading. There is another illustration in which the shield can be seen. The conventional (thought not the only) view of hoplite warfare is that the two opposing lines would meet shield-to-shield and fight from there. The Macedonian phalanx instead used the sarissa to pin the opposing line in place rather than engage it directly. Their shield was smaller and not well suited to the shieldwall tactic of the hoplite.

Wait is this the start of a new series?!?! Or have I missed them?

This is awesome! I love ancient warfare and learning more about them. Some rulesets I’ve been reading up on include Hail Caesar and Field of Glory Ancients, and this makes me want to start a collection prematurely.

It’s the second one of five. There’s a link to the first one at the bottom of this article 🙂

All that fighting and no Spartans involved ?

None. After they were defeated by Thebes they largely stayed out of Greek affairs for the next few decades. Due to their location in the south of the Peloponnesian peninsular it was easy for them remain isolated from events to the north,and they declined to join Philip’s Greek coalition or Alexander’s invasion of Persia. The year after Alexander crossed into Turkey, Sparta attempted to capture Crete but were defeated by a Macedonian army. A little over a century later they attempted to capture control of the Peloponnese but were crushed again by a Macedonian army.

Thanks for the explanation.

If anyone is interested in this kind of thing, the late great David Gemmel wrote two novels about Phillip and Alexander called the Lion of Macedon and the Dark Prince respectively which are best described as “Historic Fantasy”. I use the word fantasy rather than fiction because there are some fantasy elements although it generally follows the life and events of the two Macedonian Kings. This battle is featured in the second of the two novels I believe.

I was wondering what happened to this series, @redben . 🙂 Glad to see it return. We need all the historical content on BoW we can get. One question – in his “Virtues of War,” Steven Pressfield novelizes the military career of Alexander (not sure if you’re familiar with this book). Its the same writer that did “Gates of Fire” (Spartans at Thermopylae . . . CORRECTLY . . . f*** you, “300”), “Tides of War” (Alcibiades in the Peloponnesian War), etc. Anyway, he’s considered something of an authority on classical military history, but when he stayed into WW2, his… Read more »

The thing about historical fiction is that whilst it’s historical, it also fiction lol. As I briefly mention in the article, we’re not blessed with many surviving sources on the battle. We get a brief description of the battle from Diodorus Siculus and a brief account of Philip’s feigned retreat from Polyaenus. Neither make any mention of the Sacred Band, for that we have to turn Plutarch’s Life of Pelopidas. He says that Philip wept when he came across the three hundred bodies, all of whom still lay where they had fallen battling the phalanx. It would seem that Pressfield’s… Read more »

as far as i can remember the Sacred band refused to surrender to Phillip and were wiped out to a man and the unit never recovered, i think also the Macedonian phalanx’s were very superior to the Greeks as the Sarissa was so much longer than the traditional Hoplite spear that the Greeks could hardly hit or effect the Macedonians, i remember reading somewhere that king Phillip specifically created the sarissa phalanx’s for this very reason. But it would still be an amazing battle to fight on the table top for sure 🙂

There’s no question that Macedonian phalanx was superior to its hoplite cousin. It proved that time and again on the battlefield. However, Diodorus’ account of this battle tells us that it was long and fiercely contested.

The primary role of the Macedonian phalanx was to pin the enemy line down. It would then be up to the cavalry to punch a hole in the line.

Nice to see more historicals on Beasts of War! And a proper article to boot, not just a “Manufacturer X just released Y” (not that I dislike those, but there was more meat here). 🙂