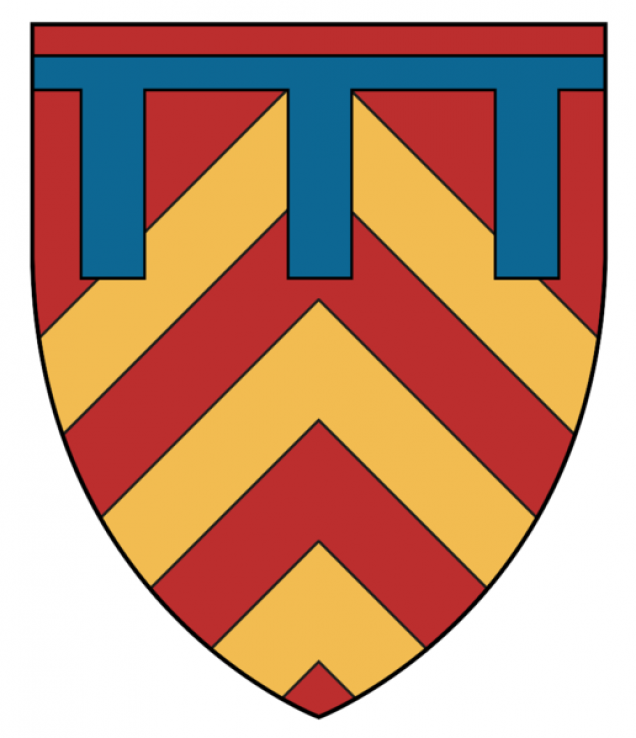

PanzerKaput Goes To Barons' War

Richard de Montfichet

The largest group represented on the committee of Twenty Five was not so much the hard-line barons from northern England as the leading landowners of East Anglia and the south-east. Once the movement of rebellion against John had gathered strength and spread out, it was these men who were at its head and who, after June, took the lead in enforcing the Charter. One of these home counties lords was Richard de Montfichet.

Richard was possibly drawn into the rebellion against John by his kinship ties with other rebel barons. His grandfather, Gilbert, had married Aveline de Lucy, the aunt of the rebel leader, Robert FitzWalter, and further back still, William, the first holder of the Montfichet barony, had been married to Margaret, daughter of Gilbert de Clare, earl of Hertford, forebear of two other members of the committee. Richard’s own sister was to marry William de Forz, yet another member. It is by no means clear, however, how kinship ties fitted into the matrix of baronial motivation alongside such other factors as personal grievance and questions of political principle. Quite possibly, their principal role was simply to reinforce decisions already made.

Richard (after 1190–1267) was the eldest son of Richard de Montfichet (d. 1203), a servant of Richard the Lionheart, and his wife Millicent. He was a descendant of William de Montfichet (d. before 1156), whose barony of Stansted Montfitchet (Essex) comprised nearly fifty knights’ fees, and from whom he inherited a claim to the custody of the royal forests in Essex, forfeited by his grandfather, probably for his part in the uprising against Henry II in 1173-4. The younger Richard came of age before 1214 and in that year served on King John’s failed expedition to Poitou in western France. Shortly afterwards, however, he is found on the rebel side, perhaps in the hope of recovering the rights forfeited by his family under Henry II, perhaps too as a result of the pull of the kinship ties already mentioned. On 21 June 1215, just six days after the king had given his assent to Magna Carta and by which time he had probably been named to the Twenty Five, he secured restoration to the custody of the forest of Essex, once held by his ancestors.

After the papal annulment of Magna Carta and the renewal of civil war, Richard remained in the rebel camp and was captured at the battle of Lincoln in May 1217. In the following October, after the French withdrawal, he returned to the royal allegiance and recovered his lands and rights, including custody of the Essex forests. He was to be a witness to two of Henry III’s reissues of Magna Carta, the first in 1225, the authoritative reissue, and the second in 1237. In 1244 he was a baronial representative named to consider the king’s request for a grant of taxation and so probably had a hand in drafting the remarkable scheme of government reform of that year recorded by Matthew Paris in his chronicle. From 1242 to 1246 he served as sheriff of Essex and Hertfordshire.

Richard was married at least twice but left no male heir and on his death in 1267 his estates were partitioned among the children and grandchildren of his three sisters. Living to over 70, he was the longest-lived and last surviving of the Twenty Five Barons of Magna Carta.

Among his estates was to be numbered the manor of Wraysbury in south Buckinghamshire, on the banks of the Thames immediately facing Runnymede and Old Windsor. It is not recorded what role, if any, Wraysbury played in the events of June 1215.

Leave a Reply