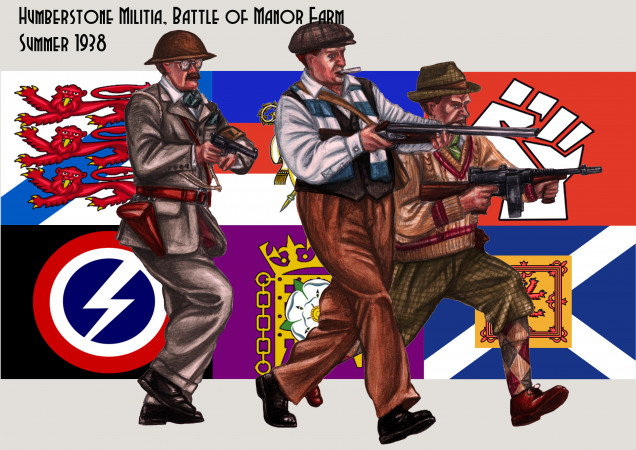

PanzerKaput's Illustrations

Background to 1938 A Very British Civil War, Part One

Coming to the end of my journey with a little bit of background history into the events that started 1938 A Very British Civil War.

The Crises in Monarchy and Government

On November the sixteenth 1936 His Majesty Edward VIII invited Prime Minister Baldwin to Buckingham Palace. The matter for discussion was the King’s intent to marry the American divorcée Wallis Simpson. The Prime Minister indicated that the Government would not and could not support Edward’s marriage, telling the King that if he wished to marry Mrs Simpson he must abdicate. If the King refused the Government would be forced to resign. Prime Minster Baldwin already had it from the other political parties that if that was the case they too would refuse to form a Government. A constitutional crisis loomed.

By the end of the month King Edward VIII, buoyed up by the support of the “King’s Party” of politicians and aristocrats, chose to call Baldwin’s bluff. On December the seventh he summoned Prime Minister Baldwin to an audience at Buckingham Palace and informed him that he saw no reason to give up his affections for Wallis Simpson or his throne and so would do neither. With a heavy heart and true to his word, Baldwin tendered in his resignation. Over the next few days, and despite his best efforts, Edward was unsuccessful in persuading the leaders of either the Liberal or Labour parties to agree to form a Government. Even Winston Churchill, a long-time friend and the most prominent member of the King’s Party, refused the post, recognising that public support for the King was on the wane.

Mosley as Prime Minister

Finally, King Edward VIII turned to his friend Sir Oswald Mosley. Mosley, who had held a Government post in the past but, was not in Parliament at this time, agreed to Edward’s offer and on December the eleventh his appointment as Prime Minister was announced by the Palace.

His unelected status, as well as his extremist politics caused outrage in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, with members on all sides of the political spectrum walking out. Although under pressure from Mosley, Edward was keen to maintain as much of the governmental system as possible and so refused to dissolve Parliament. Instead those MPs and lords who did not take their seats were merely recorded as absent, and the Mosleyite Government presided over a rump parliament of pro-monarchists and men who felt it might still be possible to influence government through the regular channels.

The appointment of Mosley as prime Minister sparked major protests across the country. An Autocratic Monarch and a Fascist Government combined to bring out even the most moderate. In areas where fights between socialist and right wing organisations had already been regular occurrences, such as Newcastle and the East End of London, the violence became ever more extreme as Mosley’s party, the British Union of Fascists, feeling more secure with their leader at the head of Government, sought to end the Socialist Movement once and for all. A rapid escalation saw many inner city areas divided along factional lines, with barricades being erected and armed men launching raids into rival zones.

1937 The Purging of the Guards

By the end of February 1937 it was clear that the regular authorities were unable to cope with the levels of violence and protest. There were increasingly desperate calls from the Chief Constable of various areas for armed support. King Edward VIII was unwilling to use soldiers against his own people and unsure that the army, many of whose officers were distrustful of Edward’s pro-German sympathies, would obey such an order. Instead he granted approval for the raising of Auxiliary Constabularies, equipped and structured along military lines and financed by the War Department, who were to “assist and support the regular police authorities in disbanding militant organisations and restoring order”. Whilst their deployment gave the authorities the upper hand to begin with many saw them as an example of Personal Rule and, remembering the reputation of the Black and Tans in Ireland, resolve hardened and previously quiet areas saw protests and violence.

It was an obvious and simple act that finally resulted in the unrest in England becoming a full blown civil war. On the twelfth of May the Edward VIII attended at Westminster Abbey for his coronation. Security was incredibly tight and whilst soldiers of the Guards regiments lined the route form Buckingham Palace to the Abbey it was the Metropolitan Auxiliary Constabulary, made up predominantly of Fascist party members and already being recognised as ’Mosley’s Legion’ who stood behind them watching the crowd.

The King was traveling in a closed car; the traditional state coach had been deemed too risky a proposition. As it turned into Parliament Square shots were fired – some said from the crowd, others claimed it was Guardsmen or even the Auxiliaries. The result was pandemonium. The car roared off for the safety of the Houses of Parliament whilst the Auxiliaries started randomly firing into the crowd. The guardsmen turned on the Auxiliaries and for about a quarter of an hour the square was a battleground between the two, before senior officers were finally able to restore order.

Almost immediately Edward instructed Mosley to declare martial law. All major cities were brought under a curfew and the Auxiliaries were given even stronger powers. The King and Wallis fled to the safety of Madresfield Court, a stately home near Worcester.

In the days following the assassination attempt rumours over who fired the shots was rife. Amidst claims that they had been the ones to open fire on the King Edward and Mosley had the British based battalions of the Scots, Irish and Welsh Guards disbanded entirely. Whether or not any of the soldiers had been responsible for the attempt on Edward’s life, all had had their honour impugned and, left without jobs and prospects saw this as a stab in the back.

Ironically the declaration of martial law had seen the militarisation of a number of left wing and anti-monarchist forces, including the Anglican League, as they sought to protect themselves from the attacks of the Auxiliary Constabularies, who were tasked with shutting them down. Mosley and Edward finally deployed Regular and Territorial Army units in an attempt to quieten the counties. As part of a conciliatory approach it was decided that the regiments should remain in their home counties in order that the sense of armed invasion by outsiders should be minimised. It was to prove a costly mistake for the government.

Leave a Reply