Retro Recall: Ludus Latrunculorum

March 5, 2019 by ludicryan

Good news ancient board game fans (all three of you)! I’ve busted out of the room they locked me in so that I can deliver the truth. A truth that is thousands of years old which speaks of the enduring phenomenon of play in every corner of this spinning marble. This week that truth is represented by the Ancient Roman board game Ludus Latrunculorum!

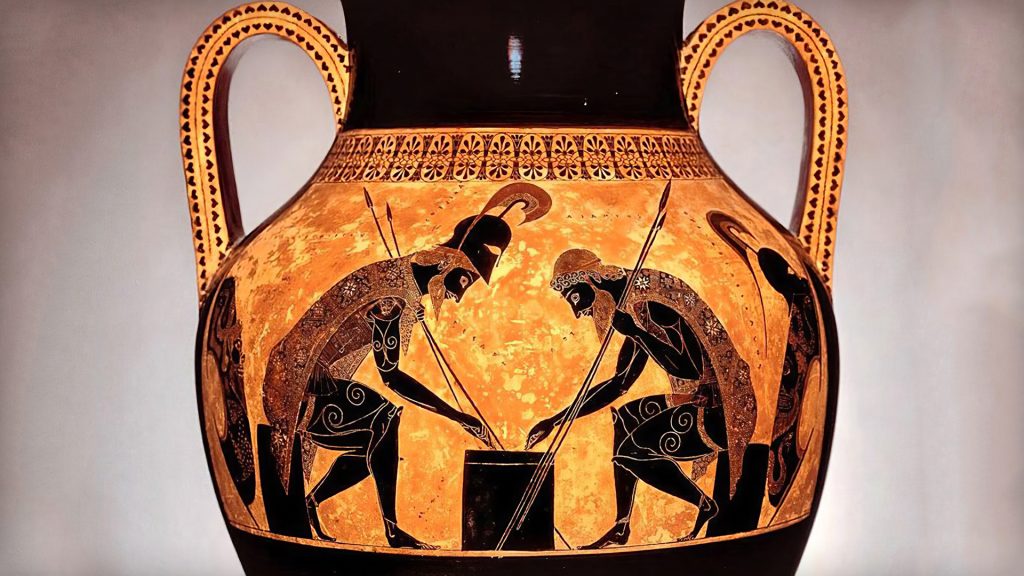

Sometimes known as Latrunculi, this board game and its related cousin from Ancient Greece, Petteia, have mentions in poems and writings from Varro, Ovid and even that smooth talker Plato. Even less is known about Petteia but its connection with Latrunculi comes through its capture mechanic of custodianship.

An Ancient Greek amphora painted by Exekias in 530 BCE depicting the Petteia match played between Achilles and Ajax

How to Play?

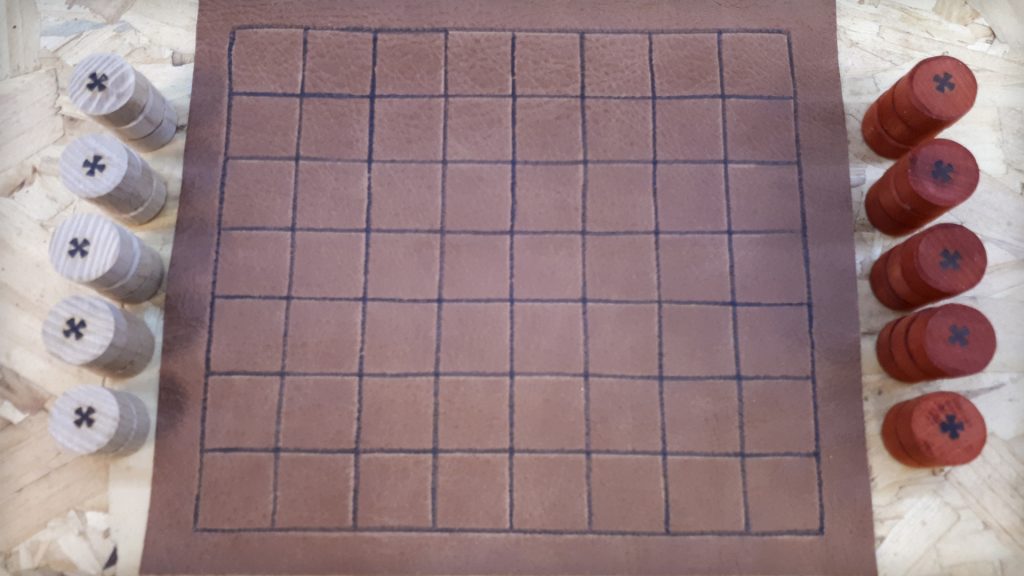

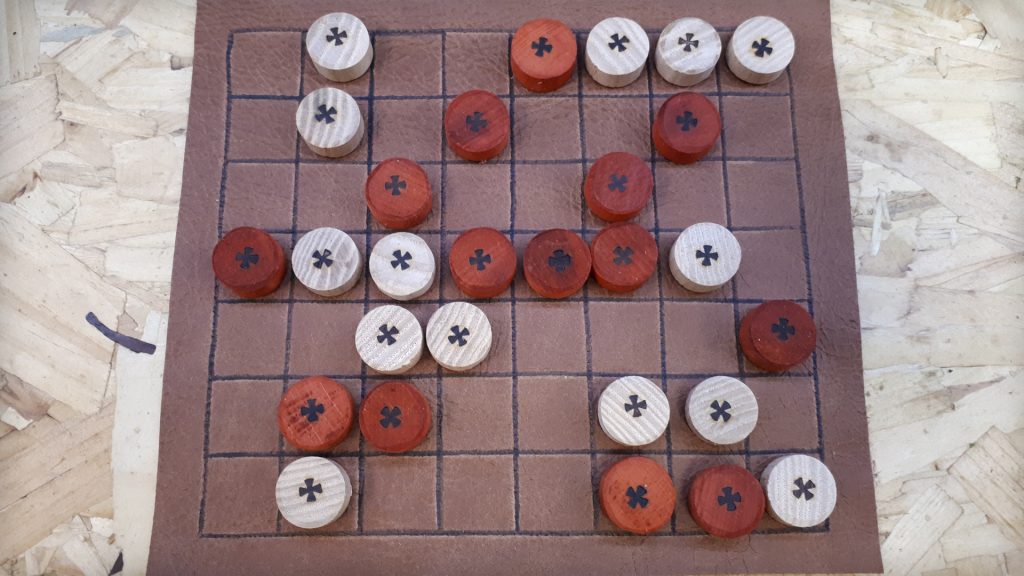

It’s mentioned as early as the 1st century BCE and the game appears to have fallen with Rome itself in the 5th century CE. All those wonderful poets and philosophers, unfortunately, didn’t think to write down the full ruleset so unfortunately, we can only make educated guesses and reconstructions based on these suggestions. There are quite a few reconstructions from Ulrich Schädler to R.C Bell to Kowalski. The first reason for these different reconstructions is the number of variant boards discovered between 8x7, 8x8, 8x12 etc.

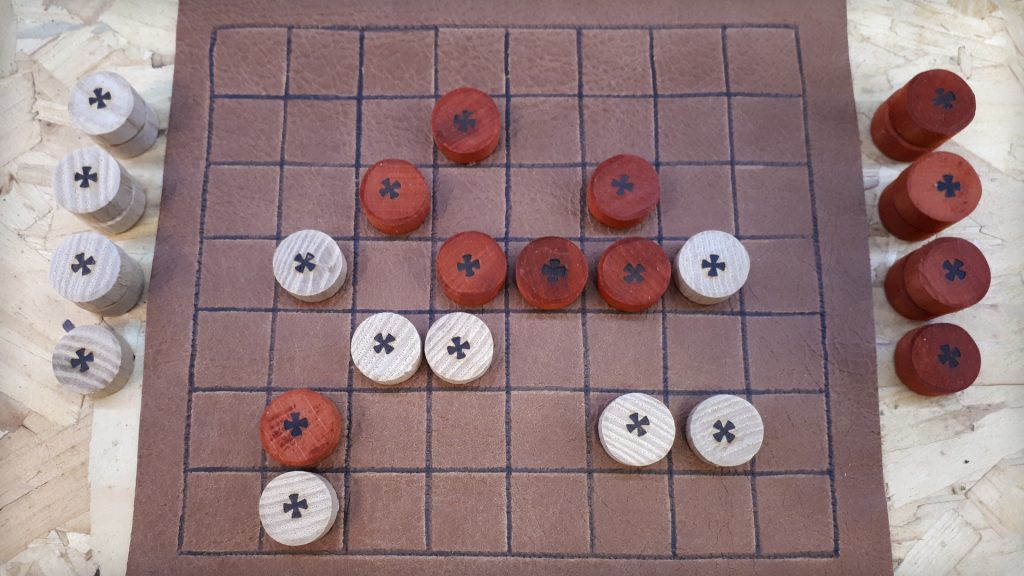

Schädler and Bell also believe that there are two phases to the game with the first regarding piece placement and the second being movement. Kowalski believes that each piece starts on a players respective first rank on the board and that the game begins with the movement. This detail completely changes how the game unfolds. The two-phase idea constructs an almost ‘Go-like’ dynamic in the first phase, followed by a phase of immediate enemy engagement. Whilst the Kowalski method creates a ‘traditional’ strategic dynamic that you might be more used to in Chess and Draughts.

There’s an interesting passage in regards to the movement of the pieces which can be interpreted in a few different ways depending on the supporting material consulted:

“Longo venit ille recessu qui stetit in speculis”

‘He who was standing on watch comes up from a distance’. Kowalski uses this to say that each piece moves like a rook in Chess: any distance orthogonally. Whilst Schädler believes this to be inconsistent with other sources and decrees that each piece can leap over others both friendly and enemy like in Draughts (not capturing them).

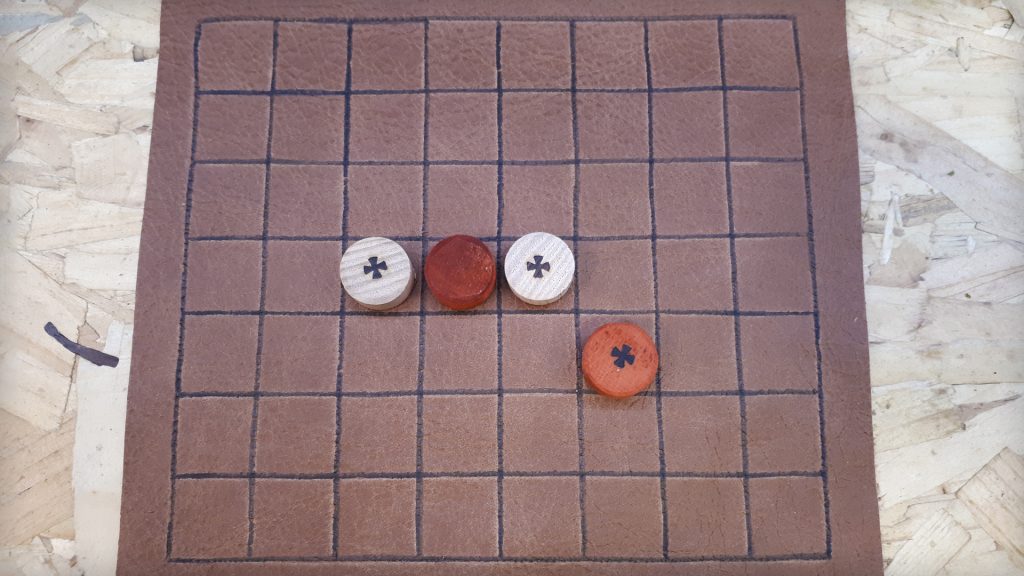

Capturing is by custodianship: surrounding your opponent’s piece with two of yours on either side. There is an interesting addition made by Schädler to this mechanic, however, in that the capture is delayed until the next move. The white piece below is trapped and cannot move. It can be saved, however, if one of the black pieces flanking it is in turn trapped by another white piece.

Something absent from Schädler’s ruleset but prominent in Bells and Kowalski’s is the Dux piece. Operating like a general, the Dux is categorised by a few things: having increased movement options in comparison to the regular pieces, in Kowalski’s ruleset it becomes a potential game ending piece like the King, and its quacks don't echo.

What is it like?

Because of the three reconstructions of the ruleset, it’s actually quite hard to give an overview of what Ludus Latrunculorum is like. I have primarily played the Schädler variation because the set I have is specifically constructed for that ruleset (reversible pieces, no dux, 8x7 board). Interestingly it feels like Alquerque in some ways, especially in the second phase of the game where the board is almost filled with pieces and it becomes a bit of a capture frenzy. This is probably not ideal play though because as space on the board starts to empty the opportunities to capture an opponent’s piece without sacrificing one of your own become limited. And if you’re not in the lead, like in Alquerque it can be quite difficult to overtake your opponent.

So this suggests an important focus on the first phase of the game where players take turns placing their pieces down on any space on the board. It doesn’t feel like Go because pieces cannot be captured during this phase but tactical considerations here must take the second phase into account. It is foolhardy to leave a piece out in the open by itself it seems. Pieces should at least be paired, which is accounted for in R.C Bell’s reconstruction.

Ludus Latrunculorum was a game that expanded in popularity with the Roman’s own conquests across Europe and West Asia. Boards were found in Slovakia, England, and Libya. Like a lot of games from the ancient world, it’s rules haven’t survived. But the proliferation of Ludus Latrunculorum shows us that the will to play was just as alive then as it is now.

Which Roman emperor do you think was probably the best at Ludus Latrunculorum?

"Sometimes known as Latrunculi, this board game and its related cousin from Ancient Greece, Petteia, have mentions in poems and writings from Varro, Ovid and even that smooth talker Plato."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

an interesting read is this game older than chess or do you think they sort of coevolved with each other?

chess is about 500 younger than this, coming from India back towards the mediterranean through the persian empire.

Well, Ludus Latrunculorum first appears in records around 100 CE whilst Chess arises from India after 700 CE. However, Chess comes from Chaturanga which can maybe be traced to 600 CE. But it would take a long time for Chess to evolve into the game we know today as it travelled both East and West inspiring new types of games and variations like Xiangqi in China and Janggi in Korea. So many fascinating games have been made in the Indian subcontinent. In particular the original Snakes and Ladders – Gyan Chauper – has a fascinating balance that was changed when… Read more »

great stuff Ryan, love this type of article. It’s amazing that some things have survived long enough to give us a tantilising glimpse into the genesis of gaming. I wonder if the board sizes were geographical variations, with some areas settling on their own preferred board size. Or gaming variations, in the same way that we can play larger games on larger tables that we know will require more time to complete and multiple board sizes occurring simultaneously. Perhaps it was even a time variation, with the rules adapting and the style of game changing with the fashion. This is… Read more »

Thanks Gerry. It certainly is fascinating! I could talk about ancient board games all day. I’ll bring in Ludus Latrunculorum next time you’re in for a game!

You could just see back then two guys arguing over a move just like player’s today over that killer winning move.