'The Fighting Third' Peninsular War Army

The 5/60th American Regiment

Peninsula Battle Honours: Rolica, Vimiera, Talavera, Busaco, Fuentes d’Onor, Albuhera, Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, Salamanca, Vittoria, Pyrenees, Nivelle, Nive, Orthes, Toulouse, Peninsula.

Celer et Audax (Swift and Bold)

Regimental Motto given to the 60th by General Wolfe

The British Rifleman’s place in popular history has been guaranteed through Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe series. They were the elite skirmishers, at the front of technological and tactical advancements in an age that had, for the most part, seen little progress. To an observer, Napoleonic warfare looked very similar to that which had come 100 years previously. The sheer scale of armies had increased vastly with industrialisation, weapons were lighter/easier to use, but warfare was still conducted by close formations of men firing smoothbore muskets with cannon softening up targets from range and cavalry providing the ‘shock troops’ of the age. While this is definitely an oversimplification of affairs it is still a rather accurate one. Rifles then, tore up the rules of engagement to an extent.

The British first saw the advantages in a new type of soldier through their experience in America where rifle armed sharpshooters had proven their worth in the dense terrain, taking out officers and sergeants with well-placed shots before melting back into the wilderness. In 1797, a 5th Battalion of the 60th Royal American Regiment was formed on the Isle of Wight to serve in America and made up largely by men of German decent. They would wear green jackets to better fit in with the forests of the New World Colonies and were to be armed with rifles.[1]

When Wellington landed in the Peninsular he recognised the importance of light infantry to protect and repel the hordes of Voltigeurs that were characteristic of Napoleon’s armies. These Voltigeurs would shield the main French formations whilst whittling away at those of their opponents. It was for this reason that the famed ‘Light Division’ was organised; tasked with keeping the French skirmishers away. In addition to this, Wellington ensured that each of his divisions could call upon at least one company of riflemen. Whereas the 95th Rifles remained together as a coherent fighting force, the 5/60th Royal American Regiment were split up and distributed throughout the divisions. Picton’s 3rd Division had three companies attached which included the battalion’s HQ.[2]

Order dated 6thMay 1809:

“The Commander of the Forces recommends the companies’ of the 5th Battalion of the 60th Regiment to the particular care and attention of the General Officers commanding the brigades of infantry to which they are attached; they will find them to be most useful, active and brave troops in the field and that they will add essentially to the strength of the brigade.”[3]

This order would ensure that the 5/60th were present at nearly all the major engagements in the Peninsular. A history of the 5/60th attached to the 3rd Division is therefore really a history of the 3rd Division. Their role in the vanguard of British forces (riflemen were often positioned in front of the regular British skirmishers) meant that their heroics often went unnoticed and yet the cost in lives was expensive. 68 officers and 767 other ranks were killed or wounded, with 2 officers and 225 other ranks missing and yet these numbers do not take into account the numerous small skirmishes that must have sapped a significant number more.[4]All this from a starting strength of 936 in 1808.[5]

Perhaps the highest praise that the regiment received came from Marshal Soult who, in a letter written towards the end of the 1813 campaign to the Minister of War regarding the high proportion of officers falling casualty. The Marshal declared that these losses were caused by a battalion of the 60th which had a company attached to each division; that their men are “selected for their marksmanship, armed with a short rifle,” who act as scouts; that they pick off the officers, including generals and staff, and that “this mode of making war is very detrimental to us.”[6]

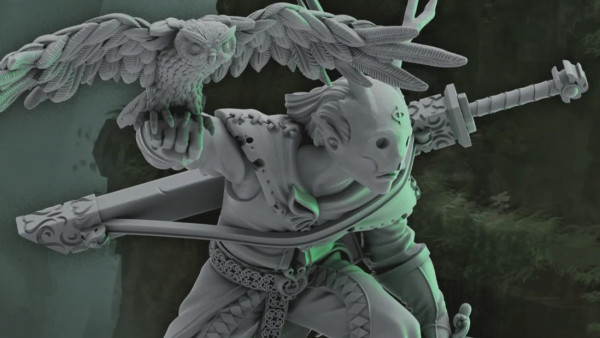

I have attempted to remain loyal to the uniform that these brave men would have worn. Their uniform was almost identical in style to that of the 95th and for that reason I have used Perry Miniatures 95th Riflemen but painted them with the scarlet cuffs and the blue trousers that they are supposed to have worn.[7]Like all of my models, years of campaigning has taken a toll on them and most of them have turned to alternative trousers to replace those that they were originally issued with. I decided to base them in pairs, as they would have fought, one model covering whilst their partner advances.

I’m looking forward to using these guys in a game but more on rulesets in a future PLOG…

[1]https://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/armyunits/britishinfantry/krrc.htm

[2]Lawford, James, ‘Wellington’s Peninsular Army’ Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 1973.

[3]http://krrcassociation.com/index.php/history/12-1758-1914/17-the-peninsula-war

[4]http://krrcassociation.com/index.php/history/12-1758-1914/17-the-peninsula-war?start=4

[5]https://www.napoleon-series.org/military/organization/Britain/Infantry/WellingtonsRegiments/c_60thFoot.html

[6]http://krrcassociation.com/index.php/history/12-1758-1914/17-the-peninsula-war?start=4

[7]von Pivka, Otto, ‘Armies of the Napoleonic Era’ David & Charles Publishers Ltd, 1979, 141.

Leave a Reply