Getting Into Solo Wargaming – Part Three

January 21, 2019 by crew

Part three of this article series will focus on the undertaking of solo campaigns. One of the primary advantages of solo games over multiplayer games is that time is less of an issue. That is, you are able to undertake gaming at a time which is convenient for you, rather than seeking to find a time of mutual convenience with your fellow gamers. This means that the possibility of playing out an entire campaign is possible. Furthermore, rather than the conventional campaign where the winner may be determined over the course of a series of ‘round robin’ or linked battles, the availability of additional time means that additional elements can be incorporated if desired to give the campaign a greater sense of realism.

Check Out @evilstu's Entire Article Series Here

While many of these elements could be incorporated into a multiplayer campaign, the additional time it would take to coordinate all phases (even if the players were fortunate enough to have a dedicated ‘umpire’ to manage such things) may result in the campaign becoming unreasonably long and result in player fatigue. I invite the reader to consider the below as a list of possible elements that may or may not be incorporated into a campaign.

If any of the elements are included you may find it preferable to cut down the level of detail in any of the phases or add increased detail for a greater sense of realism. Venerable grognards rejoice, we can turn the realism dial all the way up to eleven. Please bear in mind however that increased detail comes at the cost of increased administration, and if you are managing more than two factions in a campaign then the record keeping involved may get out of hand fairly quickly.

Additionally, the below suggestions are based loosely on the notion that the campaign is played in a generic historical or fantasy game setting. Please reframe the wording to suit the desired campaign environment of your game of choice.

Finally, all suggestions are kept generic. Specific values for any of the variables outlined below will be dependent on the pace and style of the campaign you wish to play, the length of ‘in-game’ time attributed to each campaign round and the ‘victory conditions’ determined to be appropriate.

Combat Phase

What I will loosely term the ‘combat phase’ should be familiar to anybody who has attended a tournament at their local games sore or had a round-robin games night. Everybody plays a few battles, hopefully, has a good time, points are tallied and a ‘winner’ is declared at the end. Stripping away the rest of the campaign elements, this is the core of the game system (or systems) that you have decided to use. This phase represents opposing forces meeting in conflict on the tabletop. As Part Two has outlined the mechanics of playing a solo game I will not cover in detail again here.

The combat phase on its own can effectively represent a campaign, with a faction, alliance or armies acculturated triumphs carrying it to victory ahead of its competitors. A ‘linked battle’ campaign where the result of one battle determines the location and deployment of the next is also a viable option using just the combat phase in a campaign. However, as a solo campaign affords the opportunity for greater detail in a campaign, it does seem to me to be a shame to restrict one’s efforts to just this phase…

Bear in mind that as we are considering a campaign rather than a one-off stand-alone game, that it may not be advantageous for one general to meet their opponent on the field. If one army is heavily outnumbered or has nothing to gain from the meeting engagement, they may wish to retreat and conserve their strength for a future battle. That is, it will be necessary to place oneself in the mindset of the leader of the force present (not necessarily the desires of the overall leader of the countries armed forces) and consider whether it is appropriate to engage. Bear in mind that if a force is caught off guard they may be surprised and have no option but to give battle.

As a final note, please observe that I have suggested that all of the phases may be considered optional, and that includes the combat phase. If you ever find yourself without ready access to miniatures, you may wish to play out a campaign and simply extrapolate combat results based on the strengths of the opposing armies that have engaged, the terrain available to the opposing forces and perhaps a random die roll or the turn of a card.

Movement Phase

Many more detailed or longer-term campaigns will rely on a campaign map. This map may be a paper-based map, a map on a whiteboard using magnets to track armies or pushpins on a corkboard to similarly track opposing forces, an electronic image file, spreadsheet or even a mini diorama. The important point about the map is it shows where armies may be located, terrain features of note and any applicable points of interest. It also allows zones of the map controlled by each army to be identified.

An efficient way to handle movement for a map-based campaign is to break the map into a number of provinces or territories and have each army able to move one province per game turn. Multiple armies for each side can then be tracked quite easily.

If an army moves into a province under the control of the opposing force and is not challenged, it can be assumed to have taken control of that province if it spends one campaign round in place to ‘pacify’ the populace. Furthermore, if a province is surrounded by provinces controlled by the opposing force, and that surrounded province has no army or standing garrison, it may be reasonable to assume that that province has fallen under enemy control due to being blockaded.

When an army moves into an opposing player’s province you will need to determine what force occupies that province to oppose their entry. If your campaign map indicates that an opposing army is located there then it may be appropriate to have the two forces engage. If there is no army present but the province contains a large town, fortified keep or strategically important location for the game system you are playing (spaceport, harbour, a munitions factory, teleportation circle etc) then it would be reasonable to assume that a garrison is in place to defend that area.

While the garrison is likely to be smaller than a full standing army please note that they will most likely have the advantage of a fortified defensive position (Yes, this may be an opportunity to break out those optional siege rules you have always wanted to try). If the province contains no army or strategically important locations, it can be assumed that whatever local militia forces that were defending the province wisely determine that they do not have the resources to make a stand against the invading army and lay down arms.

Movement in the campaign turn will determine what troops are available within the local area to participate in any engagements

If you prefer a more in-depth approach, you will need a sufficiently detailed map and will need to determine how far each of your armies can move in a game turn (however long a period of time that turn is determined to be). In calculating the average speed that your army can move please bear in mind that if the army is to remain a cohesive force then its rate of movement will be restricted to the movement rate of the slowest part of the force.

So an army consisting entirely of cavalry or mounted infantry may still be restricted by its supply wagons. While it may be possible for such a force to split with the quicker elements rushing on ahead to hold a position, they will then need to hold in that position rather than move in the following turn while the rest of the army catches up if the integrity of the force is to be maintained. Of course, baggage trains aside, it may be appropriate to split an army into two distinct forces should the need arise.

Terrain will also potentially hinder the movement rate of a force. If the default movement rate of your force has been calculated assuming that the force is moving over firm open ground, then it might be appropriate to impose a penalty if the ground is muddy or covered in snow, or if the army is moving through scrub or forest. Additionally, certain types of terrain may hinder or prevent certain elements of an army from moving at all – the well-worn footpath through the mountains might be fine for your infantry but may simply not be wide enough to accommodate self-propelled guns. Conversely, there may be terrain elements like roads, rail lines or canals which provide a bonus to the movement rate of the army.

Finally, if the situation is desperate an army may be required to abandon its baggage train and undertake a forced march to cover as much distance as possible in a short timeframe. The army receives a bonus to movement at the cost of combat effectiveness if they are engaged without sufficient rest time following the march. This combat penalty would represent their levels of fatigue, or perhaps exhaustion, following the forced march.

Recruiting Phase

The recruiting phase is where the armies are developed and trained, reinforced and replenished. This phase is probably best managed by assigning a numerical point value to the ‘cost’ of recruiting and maintaining fighting forces. It may help to think of these costs in a currency or form of currency or capital appropriate to the game setting in which you are operating, but for the purpose of this article, I will refer to them using the generic catch-all descriptor of ‘points’.

A shorthand method to cover this phase would be to assume that each unit has a relevant cost to equip/train/build/produce. Most, but not all, competitive wargames have some form of in-built points cost assigned to a particular unit in an attempt to achieve an approximate equivalence of balance between opposing forces, so if the game system which you are using has such an option it would be an efficient starting point to use to calculate the cost of raising a unit. If not, you may need to arrive at some methodology for calculating costs yourself. Intuitively, more elite or better-equipped troops or units would be required to be costed at a much higher points value than conscripts or the standard soldier.

Once an army is raised and you have the total point value for all units assigned to that force, the cost of maintaining that army each campaign turn may be an arbitrary proportion of that total value – perhaps 0.5%, 2%, or 10% of the cost of that army depending on how long a period of time you have determined a campaign turn to represent. That is if you are envisaging each campaign turn is a few days or a week, then a much lower maintenance percentage would be appropriate than if you were to consider a campaign turn to represent a month or season.

If you consider increasing the level of detail and complexity of this phase, a few suggestions follow...

It may be appropriate to set a point limit on the number of points worth of units a recruiting centre can generate in a particular campaign turn. For example, a poorly populated rural hamlet may be able to produce 25 points worth of new recruits per turn, whereas a large heavily populated capital city filled with industry and commerce may be able to generate and equip 750 points worth of recruits in the same time period. Similarly, the type of troops or units produced or created may be limited in certain areas, or even completely restricted to certain regions for select units. By way of example, it is reasonable to assume that a poorly equipped conscripted foot soldier could be press-ganged into service in any location in a country, but specialist equipment and technical skill, likely confined to select key regions, would be required to forge cannon barrels or build a ship of the line of battle. Consequently, it may take several turns to build an army to the desired level, with the recruits in local regions needing to wait for their comrades to be mustered to full strength at their location, or themselves being required to travel to the region where the army is forming.

Given the nature of your campaign, it is possible that not all unit recruitment need occur through conventional means

You may wish to allow for the ‘hasty recruitment’ of troops in a shorter timeframe, representing the phase at the commencement of a war where forces are rapidly being raised. In such a circumstance, a temporary increase in the point recruitment limit on a settlement may be permitted, but at an extra cost in points, resources to raise that force. For example, let's assume that a town can ordinarily raise 400 points worth of soldiers in one campaign turn. When an unforeseen war breaks out, the need to raise troops quickly is recognised, and the decision is made to divert resource to rapid recruitment of soldiers.

Let’s assume that you determine an appropriate increase would be a 50% increase in the recruitment cap, but each unit produced that turn would cost double what they ordinality would to produce. So, for that campaign turn, a 600 point force could be raised at that location. The force would be worth 600 points, contain 600 points worth of individual units, be valued at 600 points for maintenance cost purposes, but would deplete that forces point cost pool by 1,200 points for the one-off cost of raising the force. Further, it may be worth considering imposing a penalty on the fighting quality of troops raised in the manner for a certain number of game turns, representing their rushed basic training (we can assume that they get up to speed when marching off to campaign over the next few rounds).

The cost of maintaining an army may be different depending on what that army is doing or where it is located. While you may wish to use elaborate methods to calculate, a simple example may be that a per campaign turn cost of 10% of the value of the army has been determined to be the appropriate default value. This is halved if the army is garrisoned (to represent easier resupply and the reduced wear and tear on equipment) and doubled if the army is in hostile territory (representing the inherent dangers and problems in longer supply lines and increased demands for replacement of equipment and munitions expended).

So if the country was maintaining three armies, the one defending the fortified capital may coat 5% of its points value in maintenance per turn. The second army, on a defensive posture on the frontier but still within friendly territory would cost 10% in maintenance. The third army aggressively pushing through the rural farmland in the enemies territory costs 20% in maintenance per turn, as more shot is being fired and the supply wagons following behind the army must additionally fend off angry and aggrieved locals.

The cost of upkeep for such a force may be reduced if an army is trained, inclined or mandated to forage while in enemy territory, however, if this is at the complete expense of supply lines then the army may be exposed if the opposing retreating forces undertake a scorched earth policy with the territory which they are conceding. Please note that if this shifting maintenance value mechanic is utilised it will be more difficult for attacking armies to maintain their momentum, and easier for defending armies to recover theirs. This may result in a longer campaign or an increased time until an appropriate ‘victory condition’ is achieved by one side.

It may be appropriate to have a higher maintenance percentage for more elite or expensive units. If this is considered appropriate, then you would need to calculate the points value for each category of unit within an army, multiply that by the relevant percentage weighting and arrive at a new cost for the maintenance of the army per campaign turn. This may represent newer, less established technology requiring additional maintenance or repairs.

The opposite may be true for poorer equipped troops. So, a motorized infantry battalion supported by a company of newly produced, experimental tanks would cost more in maintenance than its equivalent points value counterpart comprised of standard infantry supported by reliable but technically obsolete ‘hand me down’ second rate tanks.

It is additionally worth considering that the opposing forces at the commencement of war may not be of equivalent size initially. Depending on the reasoning behind the commencement of the war, one side may have been preparing for an invasion whereas the other ‘may not have seen it coming’. In such a situation the aggressor may have a larger value of points worth of troops in the field. Of course, the non-aggressor may have seen the troop build-up and, being suspicious of their neighbour's intentions, may have countered with their own shift to a war footing.

Revenue/Economics Phase

The notion of expanding resource points in the Recruiting Phase presupposes the idea of a points pool or revenue stream of points flowing to the overall commander of a force. If a recruitment phase is utilised as above then it may also be appropriate to include a revenue or economics phase. Please note however that this may still be ignored – one could assume that each side simply commences with a fixed-point allocation of resources (representing a war chest, emergency fund, appropriation of Parliament or assignment of force resources from galactic command depending on your game setting of choice) and that the complete depletion of that resource point reserve will result in the loss of the campaign. Naturally, a second top-up appropriation could always be made later on if is narratively appropriate and you are enjoying working through the campaign…

At it’s simplest, such a phase would consist of a starting appropriation of points as stated above, plus a fixed allotment of points each campaign turn. Recruitment and maintenance costs would need to be managed in such a manner that total points reserve never dipped below zero. For those wishing to add more detail, several suggestions follow for your consideration.

One approach may be to assign a base income for each territory or sizeable town on the campaign map, and at the commencement of each campaign turn direct that region’s points revenue to the points pool of the relevant army. Using such a system, rural provinces may be of a lower point revenue value than industrialised cities. Should you wish to further refine, rural areas may be of a different inherent value depending on the nature of the available resources. A dry arid land where only a limited range of crops can be grown would likely yield fewer resources (and therefore, taxes) in a period of time than its equivalent counterpart in an area with rich soil a temperate climate and the facility to produce a diversified range of crops. Some areas may contain specific natural resources (copper mines, coal fields, timber forests, salt flats, herds of game etc) that may additionally improve the points yield of a territory.

Taking the above further, you may wish to provide a bonus if provinces with interrelated industries are controlled concurrently. For example, if one region raises cattle and its neighbour contains a tannery then you may wish to determine that if both are controlled simultaneously that it is appropriate to provide a 10% bonus to the points output of each region as resources can be more readily and efficiently directed. Similar pairings may be appropriate for any number of outputs.

If one were feeling particularly ambitious you could provide increasing bonuses the whole way through a product’s supply chain (e.g.: Cotton fields and pigment gatherer, to mill and textile dyer, through to tailor). Naturally, if resources and industries are planned to be used in such a way then these will need to be detailed on the campaign map at the commencement of the campaign.

It is probably reasonable to assume that an economy is operating at or close to full production prior to the outbreak of hostilities. This means that any redirection of resources (being either in the form of able-bodied combatants or productive output) from economic production to a combat focus would reduce the amount of productive capacity in the local area. To represent this, you may wish to impose a reduction on the point revenue generation capacity of an area (say, 20%?) in any turn where that region is performing recruitment activity. Similarly, you may wish to impose an across the board penalty on the productive capacity of all regions at regular intervals (perhaps a cumulative 5% reduction in revenue generated for all regions every 10 campaign turns). This would represent the degradation of infrastructure, depletion of a population and general fatigue of the citizens of the participating nations with the on-going war. Please note that use of such a mechanic is likely to reduce the length of an on-going campaign and eventually force the realisation of a win condition for one of the sides.

An alternative mechanic which could additionally be considered is that of an adjustable tax rate. The rate of tax could be raised and lowered as required to collect a more appropriate point revenue stream each round/ bear in mind that having a rate of tax too high will likely be unpopular with the inhabitants of an area already faced with the trials of an on-going war, and adverse consequences may occur as a result – refer to the section on politics following.

Politics

The Politics phase captures the internal machinations of the sides in your campaign. Rather than treating each side as a unified cohesive force, it might be worth considering if there are internal power struggles or political unrest on-going, and what outcomes each faction is seeking with regard to the conflict.

If this phase is to be included, it will be necessary to determine what the political or leadership structure is like for each side engaged in the conflict.

Is the side ruled by a monarchy or emperor? If so, what are the rules for succession? Is the legitimate heir young and inexperienced necessitating a steward ruling in their stead? If so, to whom do they truly owe their allegiance? Are there other factions competing to occupy the throne? Are their alternate successors claiming to be the legitimate heir?

Is the side ruled by a ruling council, parliament or government? If so, how many differing viewpoints are represented in the governing body? How strong are each of these factions relatively, and how much of a majority do they need to block or pass decrees or legislation? What outcomes are they seeking? Are their desires guided by those of their constituents, donors or personal vision?

Is the side ruled by a dictator or warlord? If so, how popular are they with their people? Do their subordinates serve out of devotion or fear? How likely is it that they will turn on their leader or one another if they perceive that they are personally at risk? Are the people ruled over with an iron fist? If so, could the opposing force sow the seeds of rebellion amongst the disaffected people? What is the plan for succession if the dictator should pass away through natural causes or more ‘direct’ means?

To represent the opinion, spirit or morale of a nation's people, a mechanism could be used where a separate tracker records the level of dissatisfaction each campaign round. Positive impacts to the dissatisfaction level for that campaign round could be caused by a nations army losing in battle that round, occupation by an opposing force in traditionally friendly territory, opposing armies foraging or looting, high tax rates or intentional intervention by agents of the opposing government with the intent of inciting discord amongst the local populace.

Dissatisfaction levels could be reduced each turn by things like campaign victories, lower taxes or direct intervention measures by the governing entity to improve the will of the people. Each round the total dissatisfaction level for the populace is calculated and added to a cumulative dissatisfaction index. When the number on the index reaches a predetermined level, or alternatively when a percentage die roll yields a result below the cumulative dissatisfaction level, an event will transpire within the local populace and the dissatisfaction index will reduce by a certain/small number (to represent the frustrations of the people being vented somewhat).

A Song Of Ice & Fire employs an effective political side to the game which could be good for inclusion in other games

Depending on the political environment, the event that transpires could be a shift towards support for the opposition democratic political party that wishes to sue for peace and end the war, outbreaks of strike action or protests, looting and rioting (possibly necessitating the diversion of military resources to subdue, and/or the reduction in economic output or recruitment capacity of the impacted regions) through to full-blown sabotage of infrastructure or a coup or revolution.

The political intrigues of courtiers, parties or ruling elites are a bit more difficult to model mechanically and will require some forethought. By way of example, if we assume that one faction is supported by merchants who want access to naval trade, then that faction may shift from supporting the war to wishing to sue for peace once the opposing force’s key port is captured.

Further, the use of diplomats or diversion of economic resources by way of enticements may be used to have other foreign powers enter the war, engage in a trade blockade against the opposing nation, or alternatively maintain neutrality and not come to the aid of the opposing nation.

Utilising this phase will require careful consideration of what the goals of each relevant faction are, how determined that faction is to achieve those goals (i.e. what is the acceptable cost to their nation as a whole of that objective being met) and how likely those goals are to be achieved. This is perhaps best handled via asking the question “How would faction X respond or react to these current events” and then implement any in-game changes that you feel are appropriate to reflect this.

Scouting

In order for opposing forces to engage one another, they need to know where they are located geographically. While you will know where each army is, each of the commanders of the armies, whose story is unfolding in the campaign, will not. Consequently, the movements and activities of each of these armies will need to be based on the information that they, not you as the player, have to hand.

A simple suggested approach to scouting is to assume that each army has a small cohort of scouts which deploy automatically into each adjacent province in the Scouting Phase each Campaign round. As armies approach one another these ‘scouting bubbles’ will come into contact and overlap.

Roll a d6 for each force. On the result of a 5 or 6, the opposing scouts detect their opposite number form the opposing army. If one sides scouts detect the other than the alert side can report back to the main army that enemy scouts are in the area – a likely sign that a sizeable enemy force is nearby, and preparations can be made for war. If neither side detects the other then both armies will continue to progress on their way as normal. If both sides detect one another, then they will need to determine if it is appropriate to withdraw or engage with their opponents. Depending on the outcome, it may be appropriate to fight a small skirmish game at this point to represent the outcome of the conflict between the scouting parties. If one side is completely wiped out, then a missing scouting party may arouse some suspicion, but perhaps less so than a positive report of scouts nearby. Note that the delayed return of a scouting party is less likely to invoke suspicion in an area traditionally controlled by the opposing force, as they could have been delayed by hostile locals or similar. If one side is defeated and still manages to withdraw with some able-bodied survivors, then treat the result as you would have both sets of scouts detected one another and withdrawn.

If the armies are adjacent to one another next turn, a similar scouting check could be made, with scouts detecting the opposing army on a 5+. So we have a circumstance where both forces may or may not be prepared for one another. If a force has successfully made both it’s location rolls, it is conceivable that that force will be on a war footing and prepared for action. If a force has been successful with one of its checks then it may be in a slightly off-balance position i.e. it has been caught off guard and has rushed to prepare for battle, or is prepared but is not sure where the attack is coming from. If a force has failed both checks then they may be caught in a column at the march or while encamped.

The results of these checks should help inform deployment options. Potential scenarios may include having a meeting engagement with two well-prepared forces, a fighting retreat by an understrength force, defence of a fortified position by a numerically inferior force against their opponents, or even two unaware forces on the march stumbling into one another.

Please note that the above-proposed detection check rolls may be required to be modified for things like weather, terrain and the characteristics of the opposing army (redcoats may be easier to spot than frontiersmen in hunting shirts). It may additionally be appropriate to give one side an ‘automatic’ scouting check each turn when a hostile force has crossed into territory traditionally held by them, as the local populace would likely observe the force and news would quickly travel to friendly commanders. For garrisoned forces defending a fortified location, it may be appropriate to have automatic observance of hostile enemy forces from an adjacent province or a number of provinces away, as they will have scouts, patrols and signal tower networks established in advance.

To add a greater level of depth to this phase, you may wish to consider having scouting forces deployed and moving as per standard armies. Scouting forces could be either a handful of stealthy individuals sneaking through enemy territory trying to actively avoid detection by enemy forces or the local populace, or alternatively a small detachment of the main army who rely on their numbers rather than stealth to protect themselves. Each turn the scouts move a province/region and checks are made to see if they detect opposing forces, using a methodology similar to the above or perhaps a more sophisticated system of your own devising.

If opposing forces are detected then the scouts will need to move back to their own lines or a friendly province to report this news (perhaps with opposing forces in pursuit trying to capture or destroy them). Once they arrive they will be able to report on the location of the opposing force at the time they were encountered – ie an opposing force of approximately 500 troops was spotted two provinces to the west two turns ago. As the information is not reported in real time it will give an indication of the presence of a force but not the current definite location.

Lines Of Supply

For an army to operate at peak efficiency it is normally necessary for it to have a line of supply back to a depot or friendly base of operation. The alternative is travelling with all of your supply and support resources accompanying the main force, which may slow its movement. A possible shorthand way to cover lines of supply is to ask if a direct line can be drawn, using roads, rail, rivers or similar, through friendly controlled towns and provinces, back to a sufficiently large city, port or base of operations to supply that army. If that can be done then the army is assumed to have lines of supply intact.

If an army cannot draw such a line of infrastructure, but the break in the infrastructure line can be bridged with an overland connection through friendly controlled provinces, then it can be assumed that supply lines are operational but at a slower rate (with supplies perhaps needing to be unpacked from the railyards and transported overland on horse-drawn carts to a river jetty two provinces away). In such circumstances, the army can be taken to be supplied at a reduced rate, and some form of reduction on combat effectiveness may be appropriate.

If an army cannot draw a line back to a supply depot through friendly provinces then the armies supply lines can be taken to be broken. The army may then be subject to increasingly severe reductions in combat effectiveness as provisions run low, potentially forcing an army to withdraw to a friendly territory to resupply. Incorporating such a mechanism means that an army may be countered by a smaller force moving on its supply lines, rather than being directly engaged on the field of battle, and should encourage some interesting strategic considerations for the generals of the opposing armies.

Large towns located at the intersection of main roads and rivers can become highly valued strategic locations

Additionally, keep in mind that some armies will travel with skilled tradesmen, artisans or specialists who can repair and resupply an armies fighting capacity to some degree. These may be blacksmiths, fletchers, mechanics or electrical engineers depending on your game setting of choice. It may be worth adding such specialists as unit options or bolt-on upgrades for your armies rosters. Additionally, as outlined previously, armies that forage off of opposing territories will be less dependent on lines of supply, and should consequently suffer reduced (or zero) penalties if their lines of supply are broken.

Casualty Replenishment Phase

Following a battle, injured soldiers will be treated, scattered units will slowly reform and fresh replacements will arrive to replenish the ranks.

The victorious army or the army left controlling the battlefield at the conclusion of an engagement, will have an opportunity to recover and treat their wounded and injured, repair damaged war machines and will benefit from having an obvious rallying point for scattered forces to return to. Following such an engagement, the victorious forces may be replenished by a decreasing proportion of their casualties suffered in subsequent rounds. For example, a unit that suffered losses might recover 40% of those losses in the subsequent campaign turn’s Casualty Replenishment Phase, 20% in the next turn and 10% the turn thereafter.

The army that does not claim the field of battle will conversely not have an option to recover as many of their wounded, and those that have fled battle or been scattered will not have a fixed rally point to return to, perhaps instead needing to travel on their own in pursuit of their fleeing army. For such a force, appropriate replenishment rates may be 20%, 10% and 5% in the following turns.

If an army loses the field and is in retreat in hostile territory, the victorious general has sufficient troop available, they may break off part of their army to pursue and scatter the residual forces, preventing them from reforming into a cohesive fighting force. If this is done for the next few campaign turns it may be appropriate to remove the losing force from the campaign completely, as it has no option to reform.

Without a defined rally point, scattered troops may find it difficult to regroup post battle

Once an army has reformed post-battle, if it has lines of supply back to a friendly resupply point it is reasonable to assume that it would receive a small number of reserves each round. This number would increase if the army is located in a friendly province, and increase further if the army is near a town, large city or recruitment centre. The rate of reserves may be impacted by the availability of new recruits. That is, recruitment levels are likely to be higher in the beginning of a war where morale is higher and a higher number of raw recruits are available and would taper off as the war progressed.

Keep in mind that if a unit has suffered heavy casualties, replenishment via means of raw recruits may reduce the inherent quality or experience levels of the unit overall. If maintenance or elite units is desired it may be necessary to combine depleted elite units into one new force and form new ‘green’ units through means of recruitment. Conversely, the elite unit could be broken up and members assigned to forces created by newer recruits. These individuals would be able to train the newer recruits and share their leadership, skills and experience, getting the newer forces up to speed quicker and improving their combat effectiveness, morale and survivability.

Armies that do not have a line of supply back to a recruitment point may not enjoy the benefit of reserves being sent, potentially requiring the army to retreat to a friendly province to replenish.

Morale & Fatigue

The inclusion of this phase will involve tracking the morale levels, and fatigue levels, of each army in the field.

Morale can be viewed as a measure of an army’s enthusiasm towards combat or their belief in success in the overall course of the war. An army’s morale may receive a bonus when they have a convincing victory over an opposing force, when they are defending their homeland or capital or when their army is doing well. An army’s morale may receive a penalty when their forces are defeated, or their army specifically is defeated in combat. The below table suggests a possible quick way of calculating morale modifiers.

- Event & Morale Modifier

- Any friendly army victorious in combat +1 morale to all friendly armies

- Army gains a major victory over opposing army +3 morale to that army

- Army gains a moderate victory over opposing army +2 morale to that army

- Army gains a minor victory over opposing army +1 morale to that army

- Army is in friendly territory +1 morale to that army

- Army is near friendly capital +2 morale to that army

- Any friendly army defeated in combat -1 morale to all friendly armies

- Army suffers a major loss against opposing army -3 morale to that army

- Army suffers a moderate loss against opposing army -2 morale to that army

- Army suffers a minor loss over opposing army -1 morale to that army

Assume that morale will naturally move back towards 0 at a rate of 2 points per campaign Morale Phase. Armies with a cumulative negative morale total may remove an additional point of negative morale each campaign Morale phase if they have rested (i.e. not moved or engaged in combat for that campaign turn). You may wish to increase this benefit if the army is in a friendly province or near a friendly capital.

Additional overall bonuses or penalties may be appropriate depending on how the war is progressing overall. I.e. the winning side may enjoy a bonus, while the war-weary defeated side suffering a faction wide penalty.

Once the cumulative morale has been calculated you may wish to apply appropriate bonuses or penalties for the cumulative morale an army is presently enjoying. Positive morale scores may provide bonuses in combat, allowing rerolls of some dies, modifiers to in-game leadership checks or similar. Negative morale scores may result in penalties to reform broken or fleeing units and have them return to combat, reductions in combat effectiveness, leadership penalties or even a reduction in the number of troops available for combat due to desertion.

Note that this means if a victorious army with higher morale continues to pursue a defeated force with low morale round after round that it will be increasingly difficult for the defeated force to regain the advantage.

Fatigue could perhaps be managed in a simpler manner. We can assume that an army has two states, either rested or fatigued. A rested army can become fatigued by engaging in a forced march, or by moving normally and then engaging in combat in the same campaign turn. Simply moving or engaging in combat within the one campaign turn should not be sufficient to fatigue a unit – i.e. they can perform either action but not both while avoiding becoming fatigued. Once an army is fatigued, they will need to spend one complete campaign turn resting (i.e., not moving or engaged in combat) to remove that fatigue. Fatigued units should suffer an appropriate penalty in combat – perhaps a reduced rate of movement or a reduction in combat effectiveness in protracted combats.

Alternatively, the third tier of ‘exhausted’ could be introduced where an already fatigued army is forced to move and fight in the same round once more. This would involve harsher in-game penalties and perhaps a reduction in unit strength for each unit. It may be reasonable to assume that an exhausted unit will require 2 rounds of consecutive rest to get back to a fatigued state, plus the normal additional round of rest to return to rest.

Weather/Seasons

The impact of weather directly on the battlefield is fairly self-evident, but it is additionally worth considering how the turning of the seasons would impact on a broader campaign. At the outset of a campaign you may wish to decide on what the local climate is like and which seasons have which effects, and apply appropriate modifiers as the campaign enters each season in turn.

In areas with heavy tropical rainfall or snowfall during parts of the year, campaign movement is likely to be substantially impaired, or perhaps even prevented, due to the ground being difficult to cross. These penalties may be reduced somewhat if paved roads are available (note that dirt roads will not fare particularly well with armies on foot using them in muddy conditions). Similarly, rivers and canals may freeze over in colder conditions, preventing transport, resupply and trade.

Ocean-going ships may be confined to port during storm seasons, simultaneously impairing trade with neighbouring nations and scattering any blockades underway by opposing naval forces.

Additionally, harvest season may provide additional revenue from farming regions or tariffs on trade exports. Finally, there may be traditional holiday periods or religious days observed by some or all sides in your conflict. Observance of these periods may provide an opportunity to rest and resupply, as well as a bonus to morale, but at the expense of potentially maintaining the momentum in an on-going campaign.

‘Hero’ Phase

The inclusion of this phase in a campaign covers off on the cinematic styled actions of small elite teams dispatched to perform key critical tasks. You may wish to think of such individuals as adventurers, special forces teams, spies or saboteurs depending on the game setting of your choice.

Dungeon Saga has a solo play supplement that could be easily implemented to handle the heroic phase actions in a fantasy campaign

It is suggested that these teams should be able to move about the campaign map in a more rapid manner than regular forces, and would be used to conduct singular objectives rather than simply the engagement of opposing forces. Such objectives may include, but are by no means limited to the following:

- Freeing a high-value prisoner from the enemy’s prison, rescuing such an individual from impending capture or capturing a high-value target;

- Destroying a key infrastructure location or facilities such as a rail bridge, fuel depot or research lab;

- Retrieving an intelligence briefing or key documents;

- Theft of treasure, resources or experimental technology prototypes;

- Assassination;

- Recovering a holy relic to improve the morale of that armies’ forces; or

- Spreading propaganda or undermining the morale of the local populace in some manner.

The success of the above could be determined randomly, or it might be an opportunity to engage in a small scale ‘skirmish’ style game to resolve. A positive outcome for the heroes would result in an appropriate positive benefit for their faction. To discourage an overreliance on this phase it is suggested that the use of such heroic teams would be accompanied by a significant points cost investment, representing the diversion of resources required to remotely deploy and then extract such a team.

Technology

Technological advancement in this type of campaign is perhaps best framed as a granular and incremental process. While some computer game franchises may have technology lifting combatants from the level of tribes fighting with sharpened sticks at the commencement of the game to the era of spaceship battles by the conclusion, the chronological constraints of a wargame campaign are likely to limit progression to more modest levels.

Additionally, bear in mind that if a new artillery piece or technique of forging steel weapons is developed, it will take time for sufficient numbers of those new items of equipment to be produced to allow for army-wide distribution. Consequently, the new equipment may only be available to select units in certain armies initially.

Note that not all technological advances have to be large or impressive. Development of improved rations may reduce attrition while an army is on campaign, improved boots may allow an army to reduce movement penalties in mountainous terrain, a new type of greatcoat may reduce penalties from exposure in colder regions or inclement weather and so forth.

Mixed Game Systems

The solo campaign allows you to mix and match any games systems which you may wish to employ depending on their appropriateness for the need at hand, regardless of obsolescence or the need for a locally active gaming community.

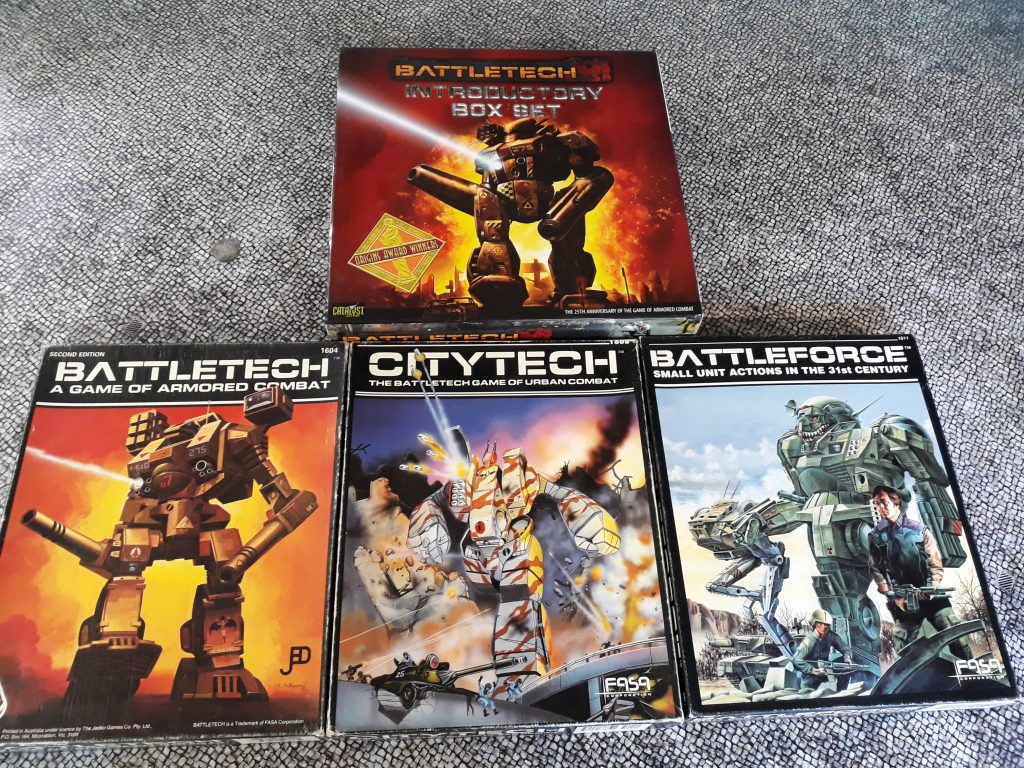

For example, if you are working through a campaign in the Warhammer 40k universe, it may be appropriate to have 8th Edition Warhammer 40k as the default game setting, but to switch to Kill Team for the activities of special forces units in the Heroic Actions Phase. For larger scale battles you may wish to switch to Adeptus Titanicus or Epic, and perhaps use Battlefleet Gothic to handle orbital engagements. Battletech, Alpha Strike, Battleforce and the Succession Wars game could similarly be combined for the Battletech universe.

Various gaming supplements can be used to add levels of gameplay to a campaign, even if they are based on a previous edition of the core game

For Napoleonics you could move between Forager, Chosen Men, Sharp Practice, Black Powder and Grande Armee depending on the scale of the engagement. Dark and Middle Ages games could be played with a combination of Blood Eagle, Saga, Lion Rampant and Hail Caesar.

For Fantasy, you could move between Warhammer Skirmish or Mordheim, Age of Sigmar, Warhammer Fantasy, Warmaster and Man O’War. For the non-GW purists the Frostgrave rules system, Dragon Rampant, Kings of War, Kings of War Vanguard ad the Ninth Age may provide sufficient choice.

The above is intended to be suggestive of potential options and not all-encompassing. The point I am seeking to illustrate is that there are many wonderful rules systems around and undertaking a solo campaign provides a unique opportunity to explore a game at a new scale or dive into a ruleset that you may have missed out on and others have now moved on from.

Victory Conditions

Reaching a victory condition, or the end of a campaign should be fairly evident when it occurs. Depending on the phases you are including and the level of complexity you are seeking to employ possible win conditions may involve one force capturing the opponent’s capital, apprehension of the nations ruler, depletion of the opponent’s financial resources, overthrow of their ruler due to rebellion or revolt or the effective destruction or neutralisation of that factions’ armies.

Of course, a likely end condition is that both forces fight one another to a standstill and are both eventually too depleted to comprehensively defeat the other, and come to terms via a peace treaty. Campaign end condition may be dependent on political and economic considerations as well as the results on the battlefield, and may further be guided by any narrative which you choose to develop around how the war commenced.

Other Options

In an effort to keep this article series down to a manageable length (yeah I know, sorry, but thanks for bearing with me this far!) there are many elements which I have not touched on. A few are listed below for your consideration and potential inclusion should you wish to undertake a solo campaign (or a detailed multiplayer campaign). Please let us know in the comments if you have thoughts around the use or applicable rules for any of the below...

- Capture of prisoners;

- High-value captives or hostages, ransoming members of nobility;

- The reputation of the opposing force or general, and the impact that this would have on an army’s morale;

- Information provided by the interrogation of captured high-level commanders;

- Units gaining experience during the campaign and the development of leaders from within the ranks;

- Siege battles;

- The environmental impact of a forces geographic location (are they exposed to the elements, suffering from altitude sickness of frostbite, losing troops in the forest or swamp when on patrol etc);

- Communication routes and the issuing of orders from the central command location to Generals or army commanders in the field;

- Disbanding units or armies;

- Detailed naval (or space) transport rules;

- The use of mercenary forces;

- Specialist training for particular units such as pioneers, engineers or improving effectiveness in a particular environmental (Mountain fighters, forest fighters) or climate (winter specialists) type;

- Trade blockades with other neutral nations and the impact that has on economies, the chance of drawing neutral nations into the conflict;

- Generic religious beliefs and the effect the presence of holy men or sacred locations may have on an army’s morale;

- The presence of healers or medics within an army or field hospitals;

- Morale or combat bonuses for having a tribe or home guard fighting in the region of its ancestral home and the impact that may have on morale and combat effectiveness;

- Historical animosity or feuds both within factions or across factions;

- The presence of neutral observers;

- Guerrilla or partisan forces;

- Asymmetrical technology levels;

- Random events such as Famine, natural disaster, failed crops, unseasonal weather, boons or windfall gains, and the economic, combat or morale impacts of these.

Well, thanks for reading along. Hopefully, this has inspired you to consider how additional detail can be incorporated into a campaign setting, and perhaps even inspired you to give a solo campaign a go. Have you tried any of the above previously? Is there anything that I have missed or that you think could be expanded on?

Please drop your comments below and let us know.

"Hopefully, this has inspired you to consider how additional detail can be incorporated into a campaign setting..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

Well this article is far more in detail than I had expected it to be. There sure is lot of info to digest if one wants to run solo campaign with that amount of detail that you gave.

Thanks @mecha82 – I sort of had to put the brakes on when the word count in the draft for the 3 parts was getting as long as a short thesis… This part was a big block of text but there wasn’t really a logical break point to split it but I figured people would mostly skim and focus on the parts that took their interest. Thanks for following along!

I enjoyed your 3 parts. However, for me personally, adding more and more detail is not what I want. I find the scenarios you bullet pointed very interesting and I am copy and pasting them into a Microsoft OneNote Gaming Notebook I keep but I do not believe that I would ever add more than one or two additional levels of fidelity to play solo. IMHO, playing solo is a commitment in time and space into itself. Since I only have a semi-dedicated space to my own, I limit my solo gaming adventures to 4hrs. Although today, I find myself… Read more »

@turbocooler your DIY game tracking system sounds intriguing – sounds like you have put some serious consideration into the development. Agree that adding more than a couple of the above elements would slow down gaming time, but theoretically the non-combat aspects could be done on a lunch break, on a bus etc without soaking up valuable dedicated hobby time if that was the approach people wanted to take. Hope the series has prompted a couple of ideas for you to add to your gaming toolbox.

It has, thank you

Excellent series of articles. Very detailed and covers alot, as mecha82 says, more than initially expected.

for myself, when i want to do solo, there is one boardgame i play, B17 Queen of the Skies. You fly a mission in a B17 and hope to make 25 missions. Missiona are about 30-60 minutes and a series of charts has all the information. if i were on a desert island, it’s my choice. As for miniatures, different but still, the planning is alot but still worth it.

@tacticalgenius had never considered the idea of a ‘Top 10 Desert Island’ game list – might be a thread idea or a weekender topic in that one 😉 Pinging @brennon @dracs

Wow I think I would need an accountant to play some of the realism you were talking about a fabulous in-depth reporting article.

@zorg point well made – my background is in numbers so I actually have a fair bit of potential number-crunching in mind that didn’t make it to the article. I don’t think I’d apply the ideas though unless I could fully automate a spreadsheet to do all the leg-work for me – A few of the above suggestions could be handled fairly simply but I don’t know that I’d consider incorporating more than a few into any one campaign personally until I had a bit of experience under my belt. Thanks for following along!

Hay I know what you mean I liked long devision at school the full page Job’s but I think my mind would go in to melt down now it’s still a good article for people to think about.

More general campaign-designer than solo-specific ideas, but thought provoking. I can see how this could be useful to create a campaign within a system where there is no campaign mode. I think I’m more likely to pick a game that has a campaign mode already within it, and then just play through it solo. I’m thinking that creating a basic AI for Kill Team or Necromunda should be reasonably straightforward – then I just need to create a warband (using the regular game rules) and play through the regular campaign. Similarly I’m planning to do that with Fallout Wasteland Warfare.… Read more »

@Dark Danegan AI systems for Kill Team and/or Necromunda sound like a fantastic idea. best of luck with the FWW campaign!

Thank you again for this, @evilstu . When I first read the title of today´s episode I thought I couldn´t contribute anything. I have played just one solo-campaign yet, though I have planned (fantasy) multi-campaigns. After a bit of thought I can relate a bit nonetheless. The solo-campaign I played is a campaign I made up for myself. I had bought the “The Walking Dead: All Out War” collector´s edition. There are many minis in it, but not all survivors were used in the single-player missions, at least not simultaneouly and in a way that is interesting and tells a… Read more »

Thanks @jemmy. Your TWD campaign sounds like it wa very enjoyable – nice to see that some of the rules you came up with were mirrored in official supplements later 🙂 I think the Warhammer General’s Compendium had similar rules form the Lustria supplement you mentioned, but in less detail. I might need to see if I can track it down… Agree that if playing more than a faction or two it might be an idea to have most of the factions as ‘AI’ or ‘NPC’ factions that simply defend their territory or slowly expand etc without needing all the… Read more »

Another excellent Solo-Gaming article- thank you @evilstu – so many awesome ideas!

Thank you for this amazing post. I have got so many amazing tricks that is so valuable for me. For the last few weeks, I wanted to make a spreadsheet on this type of topic so that I should get the instant solution when I am in confusion but I don’t have that much knowledge to make a good spreadsheet. I also tried to learn some tutorials of excel like how to make a perfect spreadsheet and [url=https://thetechvin.com/how-to-sort-in-excel/]how to sort in excel spreadsheets[/url] and so many things but really it is too boring to work. You have solved my problem.… Read more »

Thank you for this amazing post. I have got so many amazing tricks that are so valuable to me. For the last few weeks, I wanted to make a spreadsheet on this type of topic so that I should get the instant solution when I am in confusion but I don’t have that much knowledge to make a good spreadsheet. I also tried to learn some tutorials of excel like how to make a perfect spreadsheet and how to sort in excel spreadsheets and so many things but really it is too boring to work. You have solved my problem.… Read more »

this was just a terrific trilogy of articles about solo wargaming. I’m primarily a solitaire player and even though some of this matched my thinking and reading over the years I found myself rejuvenated and inspired anew to add refinements based on ideas in the articles, especially in the campaign rules. And I’m challenged to experiment with scenarios and rules for the final list in article #3. thanks much.