Bloom // Game Design

Game Design

So, for my first game design project, I wanted to put in place a few constraints. If you present yourself with the vast, unending possibilities of anything at all you can really stall your project. So I wanted to build upon some ancient board games because I love them so! I am particularly fond of one called Alquerque. Its board design is super interesting. So allow me to explain how Alquerque operates and a bit about the history of the board itself.

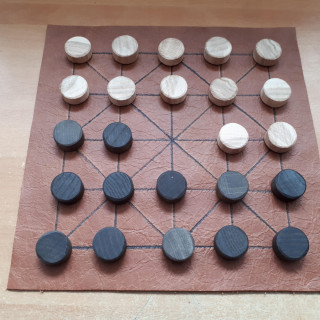

Alquerque came to the Iberian Penninsula from the Moors around the 10th century. It is known as the precursor to draughts even though it features a very different board. Its origins are found in the Temple at Kurna in Ancient Eygpt started in the 14th century B.C. The board travelled both West into Europe and East into Asia giving rise to completely different forms of games. In the East there are asymmetric examples such as Bagh Chal in Nepal and Rebels in China. In the West it became Alquerque.

History of Alquerque and the Board

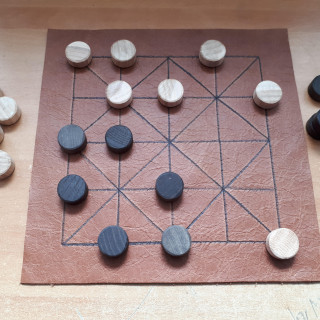

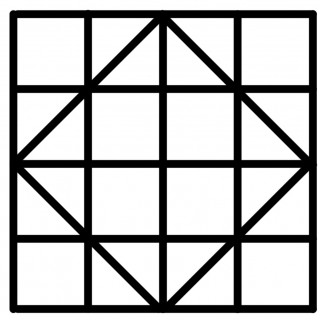

In the images above we see how the Alquerque board is used for two completely different games. The latter of which is Alquerque itself. Pieces move along the lines to another free intersection. They can capture a piece by leaping over the opposing piece on to a free spot in the direction they leaped. Pieces can only move and capture in this way forwards, diagonally forwards and to the side. More than one piece can be captured in the one move if the opportunity presents itself.

It’s a simple game that naturally involves a couple of phases. the first is a mass culling where pieces are captured by both players making a lot of space in the middle and preparing your surviving pieces for the second phase. The second phase is a slower, more careful movement of pieces where there is more space on the board. The objective is to capture all of your opponent’s pieces or capture the most if neither player can move.

You can see how the game is a precursor of draughts but what has interested me most is the actual board which is quite unique in ancient board games.

The Board Design

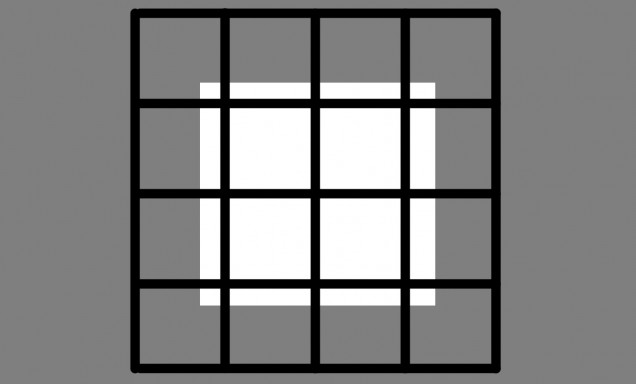

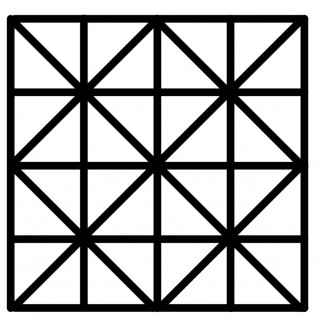

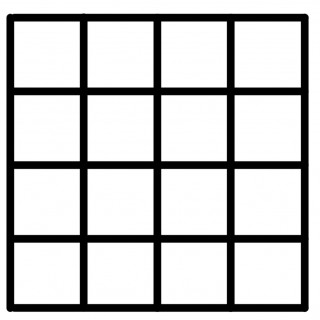

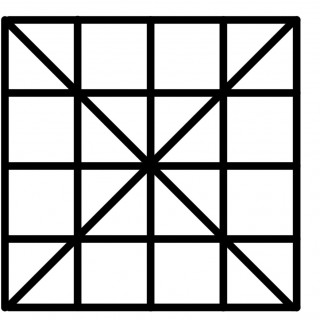

So the board is super interesting, but not all that different from a regular Chess or Draughts board. We know those to be 8×8 square grids where pieces are played on the squares themselves. Alquerque differs with pieces playing on the intersections between the squares, but we can also strip the lines of the board down to see how similar the Alquerque and chess boards are.

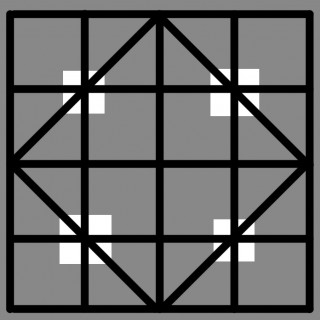

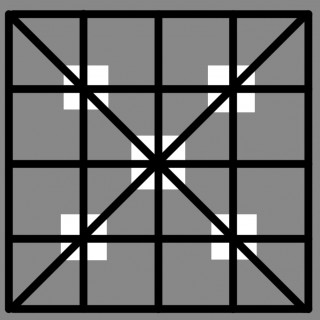

As we can see in the above image gallery, we can strip some of the lines from Alquerque to show how it makes up a grid-based board half the size of a regular Chess and Draughts board. it is when we strip down the board like this that we see its most interesting elements.

It’s quite a small board, especially if you are moving along the intersections. Some strategic thought in chess focuses on controlling the centre. When we strip back the Alquerque board to a grid-based format we can observe the centre as a 3×3 high ground of sorts.

Control of the centre revolves around these nine points which makes the additional X and Diamond lines super important to the Alquerque board. So let's look at what the additional lines do to this 3x3 'high-ground'.

Control of the centre revolves around these nine points which makes the additional X and Diamond lines super important to the Alquerque board. So let's look at what the additional lines do to this 3x3 'high-ground'.So what does all of this mean? Well let’s break it down into a bunch of bite-sized points:

- There are 56 lines that pieces can travel over and 25 intersections on the board

- From any intersection on the board, it takes no more than two movements to get a piece to the centre. Meaning this board provides a high amount of maneuverability for pieces

- There are five points on the board which provide eight movement options for pieces, making them potentially lucrative control points.

- Depending on the surrounding mechanics the 3×3 high-ground in the centre can be a powerful position to operate from.

So if I’m looking to make a game completely different to anything that has come before it on this board, how do I do it?

Designing for the Board

The most interesting part in Alquerque for me is when the board is cleared of pieces and there is more space to move around. So I wanted to design something that makes you appreciate how unique the board is. Initially, I thought about having players move pieces inside the triangles moving according to adjacent triangles. But interesting capture mechanics are non-existent and it’s a dull slog to move around the board when you have few pieces.

I experimented with other capture mechanics on the board. Using the flanking capture from the Hnefatafl family of games didn’t work because the board is too small.

So I returned to movement along the intersections, but so many ancient board games rely on capturing other pieces. I decided to experiment with capturing territory instead. When you tether the capturing of space to the basic movement along the lines a new dynamic is created for the board.

Tron-Alquerque

Though its final design pass will not make it similar to the light cycle battles in Tron, it is where a little bit of the design inspiration came from. There simply isn’t enough space on the Alquerque board to simulate these kinds of mechanics but I may try to do so in another project

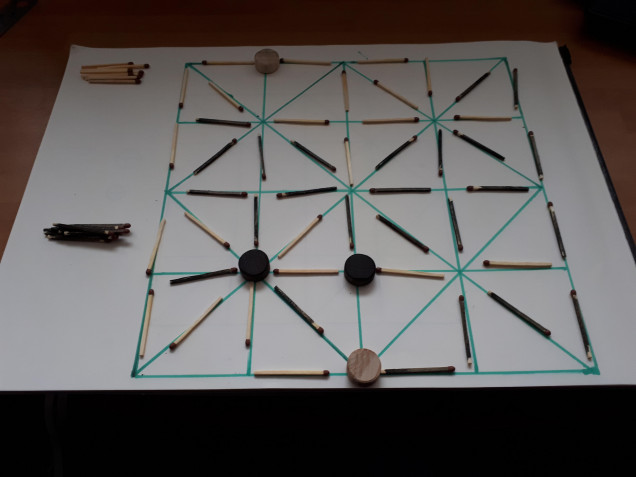

I stuck with giving each player two pieces as that frees up a lot of space on the board for movement. The original goal was for the capture of over half of the 56 lines. Players could not traverse over an opponent’s captured line. there were lots of problems with this initial design though. The objective, though interesting at first, involved a lot of backtracking in the late game and so it became quite dull. The board was also an absolute mess of pieces that easily got thrown around. The method of capture also made things quite unfair as it removed an opponents piece from the board and they would have to spend a movement to bring it back. This became too much of a disadvantage for the player that got captured first.

Matches everywhere. Pieces have to do so much backtracking in the late game. Captures are too powerful.

Matches everywhere. Pieces have to do so much backtracking in the late game. Captures are too powerful.What I did with this initial design was to focus the objective in more. Instead of trying to capture half of the 56 lines on the board, players now just have to control three out of the five main intersections. These are the intersections with eight lines running out of them. This immediately gives a direction to how each piece moves and makes each movement a greater tactical consideration. Once one player controls five out of the eight lines of an intersection then it is locked down and the lines cannot be recaptured (more on that later).

Also, pieces can move over their opponents captured territory, but they can only switch it over to their territory if they leap over another piece. In reference to this, I changed the capturing mechanic. Pieces are no longer captured, but when an opponent’s piece is leaped over the two lines they passed are captured by them, even if their opponent controlled them. This adds a lot more fluidity to movement. Players can lure their opponent’s pieces out of the 3×3 high ground with the promise of recapturing territory. This form of capture creates a very interesting dynamic between the 3×3 space in the centre and how players intend to draw their opponents across the board.

PHEW! That was quite the ramble! Next time I’ll be posting a blog about how I’ve made the components. Hopefully, they’ll not have turned out absolutely awful! 😀

Game design is a subject close to my heart, (I’ve been thinking about adding a project with some videos on game design theory!), and my own game project here came from wanting to create something with very specific constraints. You note in the description of the original game that having a point with eight movement options is a strong position. Do you think that is generally true (or just specifically in this game). I could imagine in the right kind of game a certain location having lots of movement options might be a weakness in terms of exposed fronts to… Read more »

Hai hai! Would love to see your project on game design, definitely upload it. It would be so great to have a small community of board game designers in the projects section of the website here! I think that’s a really good point about the eight-movement intersections. It certainly could become a weakness if you think in videogame terms of tower defense games or the like. But because this is a symmetrically designed game, I think it can give players an advantage for manoeuvring around the board. But yeah it also depends on the surrounding mechanics and pieces. If you… Read more »

My Deneb game project has been on here for a while, but thanks to your kind encouraging words I decided to post a new project as well, all about game design theory https://www.beastsofwar.com/project/1271582/

Yaaaaay, sorry it’s taken a few days to get to it. But I’ve been hella busy. Can’t wait to go see now! 😀