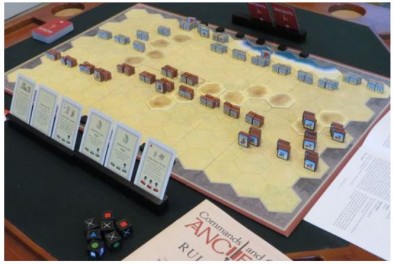

Command & Colours: Ancients // Armies Of Momentum – Part One

May 17, 2018 by crew

History, a record of the past and more importantly, the bearer of knowledge for future generations. And although learning can be fun in itself, why not make it even more so through play and if by chance you have a penchant for Western ancient military warfare, then I cannot recommend the Command & Colours: Ancients series of board games more by famed wargame designer Richard Borg.

Its magic is the simplicity of its rules (compared to most traditional wargames). There are endless scenarios and battles that can be fought as units, terrain and objectives are all modular and importantly, its short play time at about an hour per scenario after setup on average, makes it all the more likely one will play the game; or at least be willing to at least try the game rather than it sitting on the shelf like GMT’s World at War.

But there is one final ingredient that makes Command & Colours: Ancients (C&C) so special and that is its attention to its theme and historicity. We will be breaking down in a multi-part series starting today with how an ancient army works in battle.

Send Forth My Orders! (Orders)

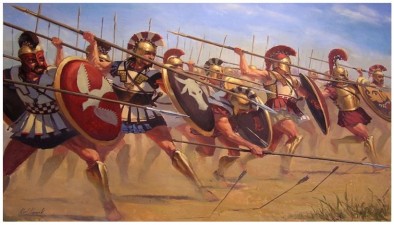

An interesting thing you learn about researching ancients armies/battles is that once a battle starts, it develops an unstoppable momentum and victory usually comes down to a lot of short-term localised decisions on the part of the commanders or units. As any wargamer knows, nothing ever goes according to plan.

The first reason being that communication was literally limited to what a person could see or hear and that an army is made up of individuals who have their own minds and more often than not, a soldier is not going to happily sacrifice himself for the good of the commander’s plan.

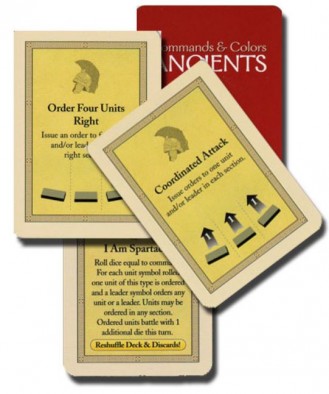

This truly comes out in C&C as you do not get to choose exactly what units you get to order in the game; rather you can only order units that are indicated on the card you wish to play from your hand of cards. In most cases, units are chosen from the three divisions of the board, left, centre and right.

In other words, you as an ancient commander have to make the best of the situation at hand, easily representing the communication limitations of the time and the real problem of units not doing the “obvious”, such as a unit staying in position and not plugging up a hole in the battle line. This is representing a period of warfare whereby more micro-managed tactical orders had to be sent from one commander to another via personal messengers.

Advance, On The Double! (Movement/Attack)

Talking of battle lines, this is the part of ancient warfare and what makes C&C stand out from other iterations of the system, such as Memoir ‘44 or Command & Colours: Napoleonics. The game’s focus is on keeping as many units as close to (or in support of) each other as possible and to only separate units when opportunities arise. This may sound easy as most scenarios are won when you have killed a certain number of enemy units, so why not move slowly and keep the army together you may ask?

The answer is firstly that many units have different movement/attack ranges and thus if you were to keep your “perfect” battleline, it would be a plodding process at best. Remember that the number of units you can move depends on your hand of cards and so in reality that would just give your opponent a lot of time to focus on weak points in your army, such as using light infantry to destroy your close combat units with missile weapons.

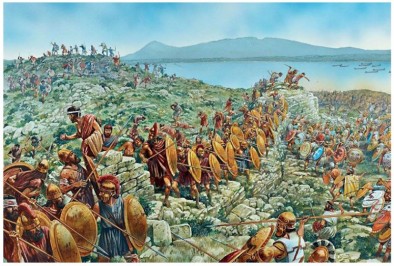

This was a strategy reminiscence of the Spartan defeat at the battle of Sphacteria, where the superior Spartan hoplites were forced to surrender when Athenian ranged units were continually killing them from afar but would retreat the moment the Spartans got within reach!

Another reason is that in C&C, the attacker has a distinct advantage and rolls damage first which is applied fully before the defender gets to attack back. Thus if you were to again move too slowly forward, you are giving the enemy commander the initiative to get in damage first and although it does come down to a roll of dice, it is not unheard of in the game for good units like the Macedonian Phalanx to kill an entire unit before it even gets to attack back.

I've Got You Covered! (Bolster Morale)

Morale is a key aspect of warfare and historical battles have proved that. A good example is the battle of Gaugamela which saw Alexander The Great fight against Darius of Persia, by which the Persians defeat was more due to the Persians routing when the King of Kings ran away than anything else. In fact, the Greeks before that were on the brink of collapse with Persians even in the baggage train behind Greek lines!

This aspect of warfare is put forth in C&C through the Bolster Morale system. The rule is if a unit is supported on two adjacent hexes by friendly units, they get a bonus to ignore the first flag rolled against them. The flag symbol is a facing on the attack die that forces a unit to run away from the enemy unit and thus not be able to attack back and perhaps even more disastrously, leave a hole in the battleline, ready for exploitation.

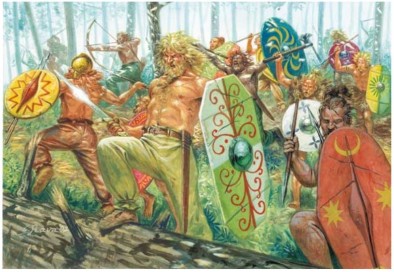

This, of course, represents the feeling of safety in numbers or the perception of it as if you look around and your comrades are doing their job. You naturally feel more confident even though you can’t see that on the other side of the battlefield the fight could well be lost. Historically, this is likened to how the early German horde armies were described by the Romans who talked of how the Germans depended on courage more than a strategy to win the day.

In fact, there is also the factor of camaraderie, which is put forth most well by war journalist Sebastian Junger on why soldiers miss war. I will link it HERE but in an injustice of a summary, it is the lack of belonging and loyalty in a civilian society that one gets among people who you depend on in life and death situations. So, you will stick with your comrades as long as you can until your flight response overwhelms your fight one.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, it still amazes me Richard Borg has made a game that can convey and teach with so little rules and yet still stays true to being a great fun game to play. Next time, we will look at the way leaders play their part in ancient warfare and how it translates in-game too.

By Akaisamurai

Make sure to also check out the review of Liberte by Martin Wallace too for more Historical tabletop game coverage!

"This is representing a period of warfare whereby more micro-managed tactical orders had to be sent from one commander to another via personal messengers..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"Morale is a key aspect of warfare and historical battles have proved that..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

I think like much stuff this got lost in the change to BoW 2.0 – Look like an interesting game

CnC:A is an excellent game, a pretty good ‘lead in’ game for people who have never played tabletop wargames and I always describe it as the closest thing to a boardgame version of ‘Rome:Total War’ you are likely to get!

Yes, an apt summary of the battles of Total war. Although, I would also preface the more historical factor about the less control of each unit due to the cards you have in hand compared to Total War, ha.

…unless your wife pulls out 2 ‘Line Command’ cards in 2 turns . . . owch

Ha, I know how you feel and you have my sympathies of being exiled from your rightful throne.

Yes, all the comments were lost for this article but in the bigger scheme of things. It is worth it for the Empire of BOW to grow and become a better website, ha.