The Saratoga Campaign Of The American Revolution – Part Two: Storm From The West

September 21, 2017 by oriskany

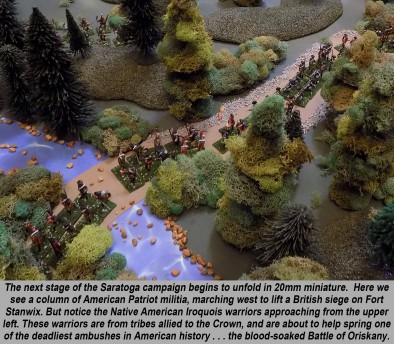

Good afternoon, Beasts of War. We’re back with another look at the Saratoga Campaign, fought as part of the American Revolution in the summer and fall of 1777. Using 20mm miniatures and TSR’s “Battlesystem” rules set, we hope to commemorate the 240th anniversary of this pivotal campaign with some great games and articles.

If you’re just joining us, we covered the background of this campaign and its importance as a turning point in the American Revolution in Part One. British General Johnny “Gentleman” Burgoyne has come down from Canada to invade New York State and seize the Hudson River, thus aiming to split the rebel colonies in half.

So far, “Gentleman Johnny” was doing pretty well. Having started his invasion in June down Lake Champlain, he’d out-positioned and taken Fort Ticonderoga (the “Gibraltar of the North) almost without firing a shot. He then won the first battle when he sent Brigadier-General Fraser to overwhelm an American rear-guard at Hubbardton.

Invasion From The West

St. Leger & Fort Stanwix

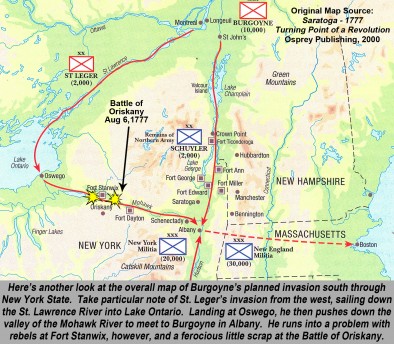

Burgoyne’s ultimate goal was to drive south down Lake Champlain, cross about thirty miles overland to the headwaters of the Hudson River, and then use the river to strike quickly south to Albany, capital of New York. There he hoped to meet up with two more armies, a smaller one approaching from the west and one from the south (New York City).

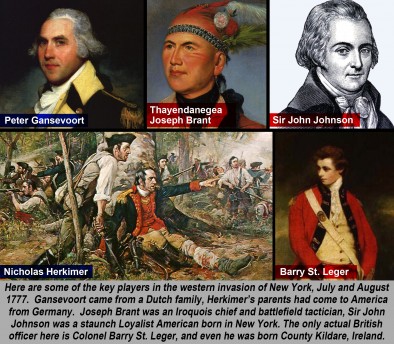

The force from the west was commanded by Colonel Barry St. Leger. Sailing from Montreal and down Lake Ontario, he landed at the town of Oswego in western New York and marched east toward Albany. His route was the Mohawk Valley, densely wooded with practically no roads.

St. Leger made good progress at first. But after a little over fifty miles, he came across Fort Stanwix. Commanded by Colonel Peter Gansevoort and the 3rd New York Regiment of the Continental Army, the fort had basically fallen apart since it was last used in the French & Indian War some twenty years prior.

Colonel Gansevoort, however, had set his men to vigorous repair. St. Leger’s Iroquois allies warned him that the fort was being re-built, but he refused to believe such extensive repairs could be effected so soon. When he arrived at Fort Stanwix, however, St. Leger learned that his scouts had been right.

With only 2,000 men (including Canadian Rangers, German Jägers, American Loyalist Militia, and Iroquois Scouts), St. Leger knew he couldn’t assault Fort Stanwix. So he settled in for a siege. When St. Leger demanded surrender, Gansevoort didn’t bother showing up to the meeting, instead hoisting a flag made from a woman’s petticoat.

St. Leger received more bad news on August 5th, when word came in that an American relief column was marching toward Fort Stanwix to break his siege. Forced to make a decision, St. Leger detached a portion of his force to intercept the incoming American reinforcements before they reached the fort.

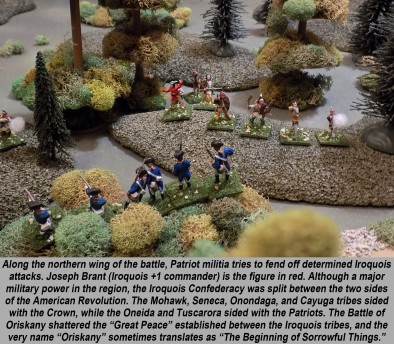

This interception force was led by two of St. Leger’s allied commanders, Colonel Sir John Johnson (King’s Royal Regiment of New York - American Loyalists), and Chief Thayendanegea (also known as Joseph Brant - Mohawk commander). In all, this interception force numbered upwards of 500 men.

This new American force was perhaps 800 men strong, made up of four regiments of the Tyron County Militia. Their commander was a grizzled but calm and cautious veteran named Nicholas Herkimer. The son of German immigrants, he preferred to speak German even though he was native-born American himself.

Herkimer had called up every male in Tryon County between the ages of sixteen and sixty. Tryon County was huge in those days (encompassing ten counties today), but sparsely populated. These 800 men were pretty much all the Patriot manpower the area could raise. Herkimer knew that if he was defeated, a huge swath of New York could be lost.

The Americans had gathered at Fort Dayton and set out on a march westward, down the valley of the Mohawk River, headed toward Fort Stanwix. Herkimer knew the route was dangerous and susceptible to ambush, a narrow dirt track winding through dense woodlands, running about a thousand yards south of the river.

Yet Herkimer’s colonels pressed him, going so far as accusing their commander of cowardice and reminding him of his relatives fighting for St. Leger. Still, Herkimer maintained a cautious advance. A good thing, too, because an ambush was exactly what Johnson and Brant had in mind. The battle would erupt at a place called...Oriskany.

The Battle Of Oriskany

America’s Bloodiest Battle?

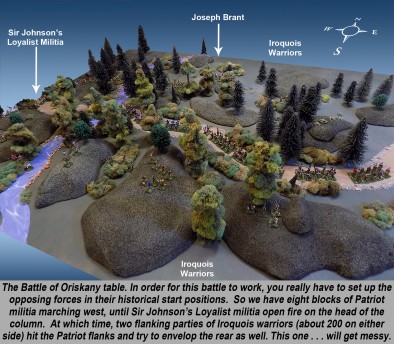

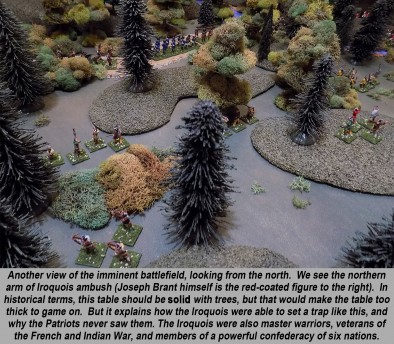

Sir John Johnson had been born here in upstate New York, so knew the ground well. So did the 350 or so Iroquois warriors under Joseph Brant (who spoke at least four languages and had been to London to visit the King of England). As such, the Loyalist leader and Iroquois chief picked a perfect spot upon which to launch their ambush.

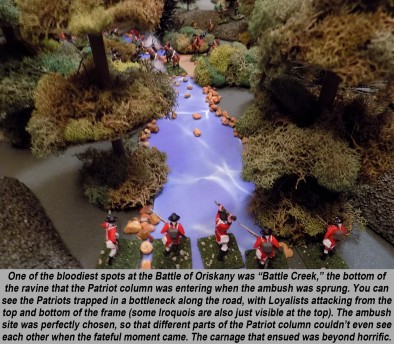

The ground here is higher to the south, and slopes down toward the north, where the Mohawk River runs east and west. Herkimer’s militia was marching along the slope, from east to west toward Fort Stanwix. Johnson set up his “Royal Greens” along a ravine to the east, concealed and blocking the trail along which Herkimers’ men marched.

Joseph Brant’s Iroquois, meanwhile, would deploy along both sides of the road, north and south, ready to hit the Patriots in both flanks and close the rear of the trap. Because of the dense tree cover, Herkimer’s column would march almost into a “sleeve” of Loyalist and Iroquois, never realizing the danger until it was too late.

Now Herkimer did have sixty Iroquois too, from the Oneida tribe, scouting ahead along with some riflemen rangers. Historians admit there is no record as to why these scouts didn’t warn Herkimer of the ambush. The consensus is that the scouts got too far ahead of Herkimer’s column, and the enemy set up after the scouts had passed.

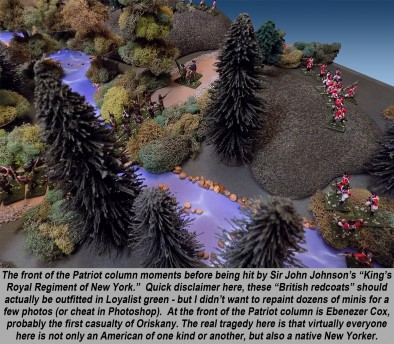

The point is, Herkimer and his officers thought the road was clear. Herkimer maintained a cautious pace (despite the goading of his impetuous colonels), but when the Patriots finally hit the end of the trap and Johnson’s Loyalists opened fire, the Loyalist and Iroquois attack came as a complete and shattering surprise.

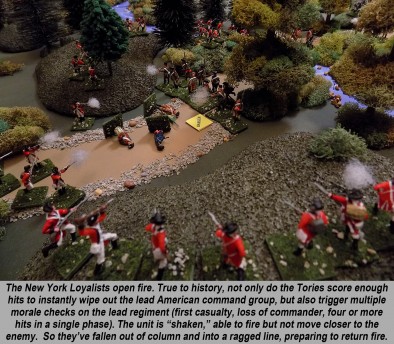

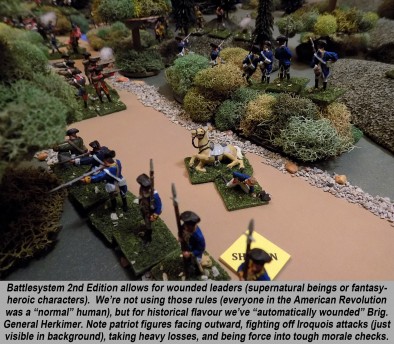

The Crown’s attack opened with three blasts on a whistle. The first volley of musketry instantly killed Ebenezer Cox, leading the front Patriot regiment. Herkimer himself and his horse was hit seconds later. Patriot militia took horrific losses to Tory gunfire, while Mohawks also loosed a volley and then charged the Patriot column from both sides.

The road, of course, exploded into blood-splattered chaos. Patriot dead and wounded were already stacked everywhere. Iroquois warriors with tomahawks, clubs, and spears were now in and amidst the Patriots armed with bayonets and hunting knives, and the fighting was hand-to-hand.

At the rear of the American column, the battle came apart completely. Most of Colonel Visscher’s regiment of Patriot militia, last one in the column, instantly disintegrated in a rout. The Iroquois attack at the part of the column had actually come a little too soon, and these Americans were able to flee in a panic.

They didn’t get very far. Despite commands to stay and fight, many of Brant’s Iroquois took off after Visscher’s militia. Almost none of them made it, skeletons would be found in the woods years later up to three miles away. But a key part of the Royalist trap was now gone, leaving an escape path open for the Patriots who remained.

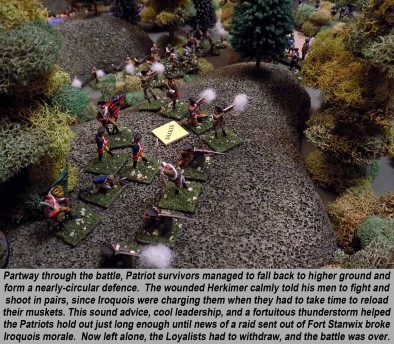

With many of the Iroquois chasing after the American rear guard, the rest of the Patriots (including Captain Gardenier’s company, the only ones of the rear guard who’d remained with the column) were able to set up a fighting withdraw to the southeast.

Herkimer, meanwhile, was showing true leadership colours. Dragged from under his dead horse and with a Tory musket ball in his leg, he ordered his saddle propped against a nearby tree where he could sit up and command the battle. Coolly smoking his pipe, he calmed his men and steadily brought the chaos under control.

Patriot fortunes continued to improve when the skies abruptly broke open in an intense summer thunderstorm. The cover was enough to allow the Patriots to further consolidate their position, falling back off the road and gathering in a circle atop a nearby hill.

The Tory Loyalists continued to push the rebel position. Some of them turned their jackets inside out and tried to impersonate Patriot reinforcements, and the ruse almost worked until Gardenier’s men spotted the deception and opened fire. This kicked off yet another melee, easily the most savage part of this bitter battle.

By this point, Tories and Patriots (both sides American) were beating each other to death with their bare hands. Exhaustion was beginning to set in, and at last Johnson’s Royal New Yorkers began to withdraw.

The battle truly ended, however, when news reached the Loyalists and Iroquois that some of Ganesvoort’s men in Fort Stanwix had sortied out and sacked part of St. Leger’s camp. The Iroquois had just lost all their supplies and all the plunder they’d collected so far in the campaign and, mightily disheartened, they simply left.

With the majority of Crown’s force having now left the field, Sir John Johnson and his remaining New York loyalists had no choice but to withdraw. Herkimer’s Patriot force, meanwhile, had also taken horrific casualties, and soon fell back to Fort Dayton.

The Battle of Oriskany was over. Technically the Crown’s forces had won, as Herkimer’s regiments never reached Fort Stanwix to break the siege. But the losses sustained by Johnson and Brant, plus the damage done by Ganesvoort’s sortie out of the fort, had grievously weakened (and essentially doomed) St. Leger’s siege anyway.

Losses had been horrendous. Accounts differ, but Herkimer’s killed, wounded, and missing had left only about 150 men of his 800 man force. Johnson and Brant lost 150-200, not counting the Iroquois that had deserted. In all, two-thirds of the men who’d walked into Oriskany wound up as a casualty in one form or another.

This casualty rate, measured against the number of men originally involved, makes Oriskany one of the bloodiest battles (“per capita”) in American history. Brigadier-General Herkimer himself would die ten days later, after a botched attempt to amputate his wounded leg.

But for the Patriots, such losses would not be in vain. St. Leger’s siege of Fort Stanwix was fatally wounded, and after some cunning bluff and trickery by General Benedict Arnold, had to be given up completely. The remains of his army had to retreat to Oswego, completely robbing Burgoyne’s main invasion of this vital support from the west.

We hope you’ve liked this second instalment in our 240th Anniversary commemorative Saratoga Campaign series. With St. Leger’s western invasion seen off, we’ll be returning to Burgoyne’s main invasion as he drives down toward the Hudson River. Post comments and questions below, and we hope to see you again next week!

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact us at [email protected] for more information!

"Herkimer, meanwhile, was showing true leadership colours [...] Coolly smoking his pipe, he calmed his men and steadily brought the chaos under control..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

"In all, two-thirds of the men who’d walked into Oriskany wound up as a casualty in one form or another..."

Supported by (Turn Off)

A 66% casualty rate puts it fairly high on the list of bloody battles in general, not just in American History. I’m no expert on this but it seems to me that smaller engagements seem to be more bloody in terms of casualty rates whereas big battles tend to be bloodier in terms of numerical casualties – most lists measure by the latter. Even Waterloo, which is a ridiculously bloody battle, only stands at about 35%. I think people sometimes overlook the savagery that has sometimes pervaded smaller engagements simply because the final figure is still low whereas I have… Read more »

Thanks very much for kicking us off @onlyonepinman . 😀 I guess I should start by saying the casualty rate (in any source commonly found) are estimations. This is because the actual numbers involved at the outset aren’t precisely known. Note these are all militias (on both sides) and Iroquois warriors. These aren’t groups that keep precise records on paper. Some sources put the rate higher, some lower. I aimed for the middle with the general historical consensus. 😀 I can tell you this much, it was pretty bad on the tabletop. With the Patriots practically surrounded (thus left with… Read more »

Doesn’t surprise me that it’s bloody on the tabletop; some of the bloodiest battles in history (and alternate history and even the future!) have been fought on the tabletop with casualties consistently reaching the 60% mark but with 100% not being a rarity. I think tabletop Generals are incredibly callous in their attitudes towards their soldiers often viewing them as little more than markers on a map 😀

There’s a certain amount of truth to that. Also, plastic miniatures never “get scared” or run away, unless there are specific rules in place that govern morale failures, etc. Battlesystem does a great job at that. Unless a unit is seriously badass (like @aras ‘ British grenadiers) they will become “Shaken” after a few figures are lost and refuse to move toward an enemy unit unless they are rallied by a designated commander figure (and make the successful morale check). Units that are shaken and hit again are in danger of becoming “Routed” – in which case they just turn… Read more »

I was actually being a bit cagey about mentioning it because I don’t want to come across as being insensitive or racist – I’m not trying to judge the people of today by the standards of the past. The Native Americans in both the French and Indian War and the American Revolution did have a reputation for ferocity and brutality in combat, particularly in hand to hand combat especially compared to the (allegedly) more civilised colonials (I use the term civilised in the broadest possible sense). But I think that the Iroquois who pursued the fleeing troops can safely be… Read more »

You bring up an important point, @onlyonepinman – this is a battle and a campaign where you have to be a little careful because of cultural considerations involved. The Battle of Oriskany is a very dark day in the history of the Iroquois people because it marked a fatal fracture of the “Great Peace” or “Great Law” that originally bound the six tribes of their confederacy together. Even today 240 years later activists are pushing for more recognition of this aspect at the Oriskany battlefield and the commemorations held annually there. Fighting out here on the “frontier” was horrific, with… Read more »

Somehow that whole post didn’t finish …

—- >>>

Also, Herkimer was hit from almost all sides, so as his forces were compressed inward, it made them ironically easier for him to physically control from his position.

We FINALLY get the story of Oriskany! Great Installment…1. The pics look great as usual.

The stream really pops and it looks like you used every tree for the board. 2. Neat detail that there were NO British (well commanders) on the British side. 3. I love Herkime. Who said a commander neads to be loud and bazen? This quiet, carful man still had the minerals to lead a battle after being shot and crushed by his horse. Looking forward to the next one.

Thanks, @gladesrunner – Yes, I used every single last tree I had. And even that technically wasn’t enough. But (1) I didn’t want to make more trees and (2) this game was actually pretty hard to play as it was trying to handle all these 20mm infantry figures among all these trees. We just used a special rule limiting LOS to 10″ Herkimer was indeed a very cool character. He knew his brigade was marching along a dangerous route and was very susceptible to ambush. He had 60 Oneida Iroquois scouts on his side, but somehow lost touch with them.… Read more »

Well done, @oriskany 🙂 To chip in on the subject above, I think that in smaller engagements the casualties rates are higher because more people are engaged. In large battles many units maneuver but don’t necessarily come to blows. The issue can be decided before that happens… or a small percentage of an army can rout, which puts the entire army at risk, and precipitates a withdrawal before most are up against the coal face. I had PM’d you about a sequel to our spring Battlesystem next year… awaiting a response. If you’re not up for it, that’s cool. I… Read more »

Sorry for not replying, @cpauls1 – it’s just been a very bumpy month. Three article series practically simultaneously, hurricanes, End of Quarter at work, and then I got very sick after the hurricane. I’m on the mend now, but I was in bad shape for a while. Honestly I don’t know about next year. Things continue to heat up at work and we may be moving house. Quite frankly I just don’t plan that far ahead. 😐 Agree with what you’re saying about the larger battles. Numbers can almost “insulate” the army’s % numbers as a whole … although that’s… Read more »

Amazing article loving this series a lot. That table looks amazing and heaps of fun to play on. Are you working from any particular book for OOB’s or finding what you can online because like you said it can be a giant pain when people don’t properly record things (the nerve of them) or no one really knows where battles were fought. Hit and miss with those wounds. Infection and disease will kill you if you don’t take it off and it can get you if they do take it off. Then you have guys like General Hood (ACW) who… Read more »

Thanks, @elessar2590 . 😀 I’ve got a lot of sources I’ve been dipping into for these battles and OOBs. But the big three are as follows: Battles of the Revolutionary War, 1775-1781 W. J Wood Saratoga 1777 – Turning Point of a Revolution Brendan Morrissey – Osprey Publishing Saratoga: Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War Richard M. Ketchum Absolutely agree about the after effects of wounds. No antiseptics, no anesthetics, “leeching,” “bleeding” and God-knows what other awful “medical practices” – getting wounded was often a death sentence in these days. It’s just sad about Herkimer because he obviously survived the… Read more »

Yeah it’s a tragic story and must have been painful.

Good thing that’s the only bad leg wound we’re going to see at Saratoga, I don’t think I could stomach another.

Ohhh … @elessar2590 – are we being sly? 😀 😀 😀

Naughty, naughty. Don’t spoil it for the others! 😀

Aha so the @oriskany handle history is divulged, by ‘eck bit tasty this fracas. Again enjoying my enlightenment thoroughly

Thanks very much, @bonesbs , Glad you’re enjoying the article series. 😀 Yes, there’s the Battle of Oriskany, the US Navy aircraft carrier that would be named after the battle (CV-34, briefly mentioned in the movie “Top Gun”), fought extensively in Korea and Vietnam, and even sci-fi starships named after the battle / carrier (Star Trek, for example, has two USS Oriskany ships, NCC 1020 and NCC 1733 – same class as Enterprise). The US Navy Oriskany is semi famous here in Florida because she was finally sunk off our state’s coast to form a large artificial reef. Already she’s… Read more »

Have really enjoyed these articles.

As odd as it may seem for a Brit, I think I am more up to speed on the American Civil War than I am on the American War of Independence. It was never a subject that I encountered at school and Uni.

Keep up the good work @oriskany

Thanks, @wesadie1969 – definitely glad you like the articles so far. We have three more to go, highlighting the Battle of Bennington, followed by the First and Second Battles of Freeman’s Farm (Saratoga). Yeah, it’s easy to say “Brits don’t know much / pay much attention to” the American Revolution because they lost. Except they actually didn’t lose. Once the larger conflict got rolling with France, Spain, and the Netherlands, the British actually came out far, far ahead (okay, they lost the American colonies but won just about everywhere else, including India, Gibraltar, and the Caribbean). Also, British historians are… Read more »

I think after the FIW the British were already turning their gaze towards India as they saw it as more profitable in terms of trade. You probably have better knowledge Jim but I have read that the British never really sent their best troops to America leaving them at home in case they were needed in Europe. The huge Deb incurred other Seven Years War didn’t help of course this could all well be myth and legend.

It would make sense, @torros, given the heavy reliance that the Prime Minister Frederick North and Lord George Germaine (Minister of American Affairs) put on hired German troops, Loyalists, and American Loyalists. The British did mount a very heavy effort once in early 1776, with a force of some 20,000 for the Howe’s invasion of New York City. But as far as I know that was really about it until the French entered the war in March 1778, and then most of those extra troops and ships went to the Caribbean / West Indies.

Thanks for the comment! 😀

@torros that’s my understanding of it also. India was seen as a more valuable asset in terms of trade and wealth and to be fair at the time it was, faced with a choice between defending the colonies or consolidating holdings in India it wasn’t really a hard choice. So Britain didn’t really put a great deal of effort into defending the American colonies and put even less into recapturing them afterwards. I think that although militarily the British lost face by being defeated, I don’t get the impression that there was a great deal of resentment within Britain about… Read more »

@torros and @onlyonepinman – all I would add to that would be possibly the Caribbean perhaps being clicked a few notches above India at the time as far as its value in a global empire. At the time of the American Revolution, both England and France held major possessions in India. The war fought between the two countries between 1778 and 1782 (final peace signed in 1783) is what established Britain as the power in India until the 1940s. The Caribbean, however, with all the sugar, rum, spices, and tobacco being grown there, had been a massive “Persian Gulf” of… Read more »

Don’t forget the American commander who was drunk in his bed miles away from the fort he was supposed to be defending, an American guard fooled into surrender by a Scotsman imitating a Southern Accent, the entire American army running away outside D.C., the President himself riding around the countryside trying to get volunteers, the British commander stealing the President’s love letters, British troops forgetting their ladders during an assault and having to go back and get them, the British army’s bad habit of having it’s commanding officer’s die, the American’s habit or using riflemen to snipe officers and British… Read more »

When you read about the war of 1812 it does sound a bit like a Carry On film

@elessar2590 – Sounds like another article series may be in your future. 😀 You did FIW, I’ve done two series on the American Revolution, you do 1812, that would leave me with Texian Independence / Mexican War . . .

@onlyonepinman – a comedy of errors? 😀

a great read @oriskany the small battles can be the worst as the troops seam to fight harder as they are fighting as friends a bit like a pub fight they know each other more and don’t want to leave if their friends are still fighting to also reminds me of the battle in the last of the Mohican’s close and personal.

The big battle / massacre scene in Last of the Mohicans is a very good analog for the Battle of Oriskany, @zorg – good call. At least the beginning of the battle. The changes would come later on, when the Patriots managed to mount a reformed defense, and fight the attackers to a standstill until they lose interest and leave. That, and there would be white combatants on both sides. In fact, at Oriskany, they kept fighting long after the Iroquois left.

For the record this game was even more impressive since it was run practically in a hurricane. Never miss a deadline! 🙂

Ha! 😀 Yeah, we boarded up the house, stocked supplies, and made up our minds to run the game, take the photos, and submit the article before we lost power, especially since we didn’t know how long we would be without power or internet.

Nothing gets in the way of hobby here on Beasts of War! 😀 😀 😀

nice commitment.

Thanks @zorg . 😀 Like we said on the other “Battle Report Thread” …

http://www.beastsofwar.com/wp-content/uploads/forumfiles/aftermath-07.jpg

Loving these articles so far @oriskany . I admit, as a Scot, I have limited knowledge of the War for Independance (even having lived in the States as a teen thanks to my Dad being posted there, being an RAF officer.) so these articles are fascinating!

Thanks, @biggrim – but you might find this interesting … the British commander (General John “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne) in this campaign gave command of his Advance Corps to probably his best general, Brigadier-General Simon Fraser, a hard-corps Scot.

Fraser out-positions and takes the most formidable American position in the area, Fort Ticonderoga, practically without firing a shot. Then he runs down the withdrawing Americans and defeats their rear guard at the Battle of Hubbardton (Part One).

Plenty more to come from General Fraser in this series. 😀

@oriskany Thought you might find these interesting

http://www.helion.co.uk/wargame-the-american-revolutionary-war.html

Hopefully these boards will open up for you soon, more flat and open terrain. Seems like playing in these dense woods is a little tough on the tabletop.

It’s true, it’s a little rough moving all these figures through terrain this dense. But such was the campaign. It really makes you appreciate skirmisher formation! 😀

Definitely an eye opener that in the bloodiest battle of the Revoution — in terms of the number of people engaged — there weren’t actually any British troops involved. Like you say above – this is what happens when a bunch of angry New Yorkers get together.

Civil wars are always the worst. but I guess you’d know that, wouldn’t you? 😀