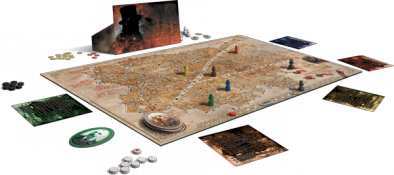

Searching The Shadows With Letters From Whitechapel!

September 11, 2013 by crew

First and foremost, let me first state that I am (what I like to call) a ‘universal’ gamer; If someone in my troupe or a new gaming friend presents me with a board/miniatures game, or talks to me about it with enough passion or insistence on sampling it, I will sit down and take the time to play it in order to give it a fair judgement.

Over the past decade of gaming with my troupe, I have moved between very different Warhammer and 40k armies and editions, I have just started getting into Warmachine, edging on Malifaux, played countless different role-play systems and at the last count, my gaming troupe has over fifty board games either we all chipped in for, or purchased individually.

In this collection, my solo purchases have been games where the written rules are exploitable to the point of hilarious (Ninja Burger; 1st edition or Sentinels of the Multiverse) or games that are so mind bendingly confusing because of the written rules, it feels like receiving a sharp blow to the head (Quarriors!). At the end of all things however, all these games possess something within their mechanics, gaming style or fluff /artistic design that made me fall in love and resulted in me handing over my geekly-earned cash.

However, in a complete and utter departure from my purchase history, I have recently acquired the Fantasy Flight Revised Edition of Letters From Whitechapel (which will be LfW from this point on); a semi-cooperative, semi-competitive, cat-and-mouse game of murder intrigue, mystery and tension. So what is it about this game that initially drew me in to buy it?

Firstly, it was the games reputation that intrigued me. Even before Fantasy Flight picked it up, I had read and watched several reviews of LfW, when the English version of the game was being produced by Nexus Games, and even then it sounded as if the game produced a very social experience for all involved (a must have for me, as my gaming troupe enjoys a game where social interaction is a key element). Secondly, the fluff of the game drew me in to purchase it; Victorian London, based on real events with playable roles lifted straight from the canon of real life. This gives the game an access point to all levels of ‘Ripperphiles’; from those with no knowledge of the events transpired, to those who have extensively studied the time period.

Unboxing The Game

Upon opening the box, this version of LfW screams quality; Fantasy Flight have a great track record of producing quality components (Battlestar Galactica and Civilization to name a few). The tokens for clue markers and crime scene markers have been refined, and the gaming screen that Jack hides behind is much improved. The board itself is gorgeous and the design certainly fits the style period in which the game is set. The only criticism I have of the components is of the police-shaped, wretch-shaped and Jack-shaped markers; it would have been great to see them made out of metal because these components are used the most.

Gameplay

I highly recommend that on the first couple of games being played, the rules are to hand for all to read; there are a few fiddly moments in the turn-by-turn setup that have an influence on the game.

One of the really useful pages in the rule book that informs how the game is played is the page detailing all the game phases (page eight in the book). This is also a somewhat deceiving page, as it appears more events take place in phase one than phase two. This is not the case. The steps in phase one, although numerous, take very little time; phase one is very much the setup for the real game, the cat and mouse of it all.

During setup, the person playing Jack records his hideout location in secret on a track record sheet behind Jack’s gaming screen. The other players take turns, draw straws (or as I have done, decided by the glorious moustaches on the pictures) to decide who is which policemen by picking the oval images. One oval image is drawn at random to decide who the ‘Head of the Investigation’ is on the game nights. I love this gaming mechanic, it can be used to be the deciding factor over disputes between the policemen ranks, or even to lead the night and make decisions for the group in later stages of the turn.

Another great mechanic in the early stages of the game is the fact that Jack’s woman tokens and the police’s patrol tokens are placed face down on the board; this means that neither side is fully aware of the others true intentions and whereabouts and can have an impact on the later stage of the game.

Once both side’s intentions and places have been revealed in the appropriate stage of gameplay, the real psychological aspect of LfW begins. The stages between “Blood on the Streets” and “A Corpse on the Sidewalk” revolve around either the Jack player’s haste or patience to kill a wretch. Jack can either kill instantly, and delve straight into the hunt, or choose to wait prolonging the suspense between players. Both sides retrieve some kind of benefit for waiting; the police get to eliminate a woman token (find out whether it’s real or fake) and likewise with Jack for the police tokens. This mechanic also gives Jack more time to make it back from the murder scene to the hideout, as Jack only has a limited number of movements before his time runs out!

Once the Whitechapel streets run red with blood, the hunt begins.

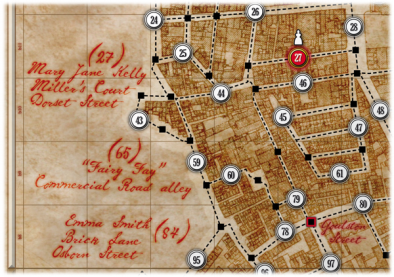

The real game begins once the murder has been conducted, and both sides possess tools to outwit and catch each other out. Jack moves along the board on the numbered circles, from his murder scene back to his hideout in any fashion he/she desires. In ordinary circumstances, Jack can only move one circle a turn but the player possesses tokens (beautifully designed coach and alleyway tokens), enabling them to move along several dots at once (coach) or slip between a housing block on the same square (alleyway tokens). These are not only useful for slipping past the policeman patrols, but can be used to deceive the coppers; the rules state that Jack must move one space on his turn, but he can always retrace his steps in order to create a rather disjointed trail.

The police can move faster than Jack (ranging from 0 to 2 steps) along the square marks on the same lines. On the end of a policeman’s movement, the controlling player can choose to search for clues, enabling any following police offers to continue searching for the trail, or if they feel confident enough, selects a single circle numbered location that they are connected to via the dotted lines and make an arrest. This ability to search for the trail left by Jack is what gives the game it’s social aspect; it gets the players talking about the possibilities of where Jack is/could have been. I realise that it sounds as if the person playing Jack is disconnected to all this discussion but it isn’t the case at all, the game play itself drags everyone in to the moment of it through discussion and psychology, as any good game should do.

If Jack makes it back to his hideout, he has succeeded in surviving the night and the game continues onto the next night. Jack can lose in different circumstances; if the coppers successfully arrest him on his current location as recorded on the move tracker, if Jack doesn’t make it back to his hideout in the prescribed amount, or if by some black magic, the coppers manage to kettle him into no legal moves (as Jack cannot move through a policeman token) Jack loses.

Review

So, why is Letters from Whitechapel worth purchasing?

As I have stated, the social aspect of this game is what separates it above other board games, if you enjoy Battlestar Galactica, I can’t recommend this game enough; it will have you tearing your hair out as the coppers or Jack in regards to the psychological/social warfare that is waged between the players. You can play the game as a very beer and pretzel game; have a couple of beers/glasses of old London port/soft drink and whatever snack you choose, but I promise, much like the celebrity guests on Top Gear, you will lean forward in your chair, engrossed in the psyche of all involved.

Another aspect is the ‘replayability’ of the game; with the design of the board, the infinite possibilities of movement on the board and the additional optional rules I haven’t touched in this review this game has a very small likelihood of gathering dust in a gamers collection. One thing I do recommend doing for anyone who buys it, is if said person has access to a scanner/copier, take a leaflet of the movement tracker and saving it to their hard drive – the box provides around three dozen of the sheets, but that won’t be enough.

However, there are some negative sides to this game.

The box says that the game is for two to six people, and that is great in itself; a game like this deserves to be able to be played in a small or large group. However, when such a great experience of the game is being able to discuss tactics, watch people squirm on their decisions and be able to look for any tells on a person’s face, much of that level of joy is taken out when it’s smaller group numbers. I have played LfW in both small and large groups on both the police and Ripper side of the game and it is much better with larger numbers.

There are also some clunky/gritty parts in the setup stage of the game and subsequent setups on the following stages of the game. There are very abrupt moments in the setup which, on early plays of the game, feel like they interrupt the flow and mood of the game as it transitions from night to night. It does aid to give pause between the separate nights, but going from being very emotionally invested in one hunt for Jack/being hunted, to setting up the next night (should Jack make it to a next night) is very jarring, it takes everyone out of the moment.

The rulebook itself is also in places poorly laid out. The rules themselves are beautiful, a great balance between Jack and the policemen, but the layout of the book and in particular, core rules that come into effect from the second night onwards are just adrift in odd clumps of text. With LfW I sat down for about 90 minutes, on my own, with the game laid out and went through the rulebook, to iron out any creases or terms I didn’t understand. If you do this as a group with the copy you buy, the first few games will last longer and the rulebook will frustrate at times, but it means everyone will be at the same pace in learning the intricacies of game play.

Here is my final, not a flat-out criticism so much but, thought. As stated previously, the gaming troupe I belong to has possession of over fifty games either group purchased, or an individual in the group has solely bought one for all to play; we have Ameritrash games (Dungeon Run, Quarriors!, Merchants and Marauders) we have Eurogames (Settlers of Catan, Carcassone, Lords of Waterdeep) and all that lies in between in some degree of one style, the other or completely separate; and that is my point.

I know the tastes, likes and dislikes of my gaming troupe; one gentlemen detests Carcassone so he doesn’t play it, one gentlemen abhors a game called Catacombs and doesn’t enjoy it, but will play it if everyone else wants to. Personally I hate Munchkin and all its variants for the simple factor that replayability is constricted by purchasing more packs (finding this out after dozens of games). I know what my friends would or wouldn’t be willing to play, so based on prior knowledge I knew that Letters from Whitechapel would be a stellar hit. It has been a roaring hit as a matter of fact and that has made the purchase worth it.

In summation, Letters from Whitechapel is an inspired game; I cannot recommend it enough to anyone thinking about purchasing it. Fantasy Flight games are currently doing a reprint of it so I’d recommend getting in there as soon as possible. This game will be played over and over, it is a beautiful game to play, and even to look at, as I sit here admiring the box artwork. Make sure however, you have the right kind of gamer to play this game; I realise that ‘the right kind of gamer’ is a bit of a flagrant statement to make, but if the wrong kind of person, and even the wrong attitude, is bought to the table to play this game, the game won’t be enjoyable to all; much like my friend sitting down to play Carcassone, the mood around the gaming table would be affected, because, to answer my own previous question, I bought Letters from Whitechapel because I knew my friends would enjoy it and the feeling of enjoyment is essentially, the essence of what gaming is.

If you would like to write an article for Beasts of War then please contact me at [email protected]

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

Supported by (Turn Off)

Reminds me of the scotland yard board game, which is set in modern times so the detectives and crook can use taxi, bus or train lines.

Thanks for the flashback to my childhood! 🙂

When I first heard of this game a while back, the first things that came to mind were Scotland Yard/Mister X/New York Chase and Fury of Dracula. I wasn’t too sure about it, but this sounds like it might be worth a try.

This looks great! An a great article too!

It’s a great game. I almost didn’t buy it as I thought it would be too much like Fury of Dracula but Whitechapel works REALLY well as a two player game (almost better than a five player) while Fury NEEDS five. I picked up a German edition back when the English version was OOP.

Thanks for the article! It looks like a great game, so we just ordered it from amazon. Really look forward to playing it.

Hope everyone enjoys killing wenches around foggy London/catching an infamous serial killer.

I have heard a lot of comparisons between LfW and Scotland Yard, a friend even remembers a game similar to LfW being in the guise of the tv show The Bill but with most FFG games it is the quality that makes it stand out from the rest.

Would be great to hear what new players thought about the smoothness of the gameplay of LfW.